This article debuts an occasional series, High Tech in the Heartland, that explores the relationship between Silicon Valley and the rest of America.

- * * *

This is not a postcard from the future: Picture a tech company’s 100th anniversary celebration where its top executives don augmented reality helmets that promise to reinvent the future of work.

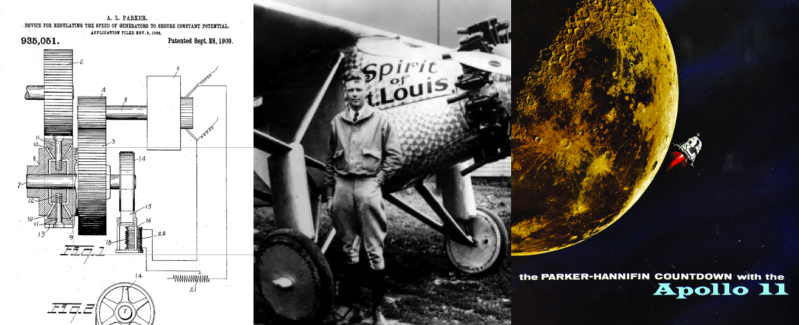

It happened just a few weeks ago. Not in Palo Alto, California but in Cleveland, Ohio. And the tech company is indeed a century old. It’s Parker Hannifin, which began building pneumatic brake systems for trucks, trains, and buses in 1917 and whose products have played critical roles in everything from Charles Lindbergh’s Atlantic crossing to the U.S. space program to the repair of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig.

Above: Parker Hannifin’s products have played critical roles in everything from Charles Lindbergh’s Atlantic crossing to the U.S. space program to the repair of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig.

“Parker has always considered itself a tech company. It’s not fashionable tech, yet it’s just as important as software and hardware,” said Peter Buca, vice president of technology and innovation at Parker.

Parker’s persistent history of innovations would be the envy of tech companies everywhere, if the generally accepted definition of what is a tech company included those based in the Midwest, the fly-over states, the rust belt. The hubris and parochial nature of Silicon Valley and the tech press is laid bare when speaking to entrepreneurs, investors, and companies across the heartland. It’s time to re-examine what it means to be a high-tech company, and to see that the heartland is not the place that tech forgot, but is a vital part of its future.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Above: Dennis Adamkiewicz, project manager at Parker Hannifin’s Fluid Connectors Group, demonstrates the Daqri AR helmet.

Ohio’s Hydraulic Valley

If California’s Silicon Valley helped birth the computing age, which accelerated supply chains, manufacturing, commerce, and helped bring bring products to your doorstep, then Ohio’s Hydraulic Valley ushered in the age of interstate trucking which, well, accelerated supply chains, manufacturing, commerce, and helped bring bring products to your doorstep.

Above: Parker’s early inventions included pneumatic brake systems for trucks.

Today Parker is a diversified industrial company with more than $11 billion in annual revenues, 50,000 employees, 8,000 patents, and a listing on the New York Stock Exchange: PH. The company provides motion and control products and technologies, namely pneumatics, hydraulics, and electronics. “Our products are used anywhere a machine moves or a machine moves someone or something,” said Buca.

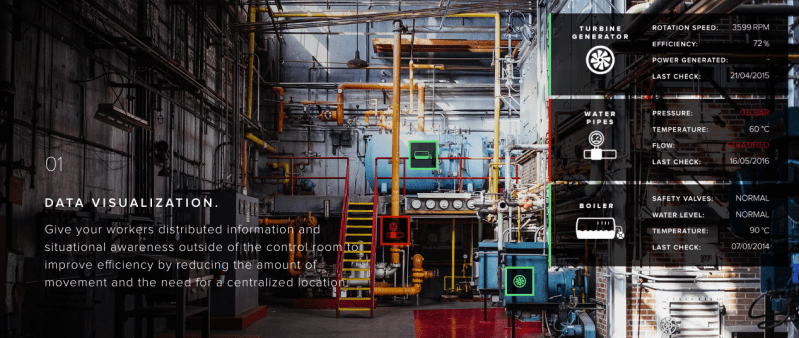

And in the future, those machines may be controlled using augmented reality. Parker sees AR as the next step in the evolution of human control of complex motion and control systems. The company has been testing AR helmets from Daqri in a pilot program for inspection processes in industrial applications, enabling humans to see and interpret data in powerful new ways.

In Parker’s world, something like a ship is not a merely a vessel but a floating building with electrical wiring, plumbing, and machinery — a giant maze of moving parts. Consider a skyscraper as a tower of the same complexity, or a space rocket, or a commuter railroad. The list goes on.

Above: For Parker, Daqri’s smart helmet represents “the next step in the evolution of human control of complex motion and control systems,” according to Parker’s Peter Buca.

Buca describes how a Parker machine is typically serviced today: A person walks up to the machine and observes it in a moment of time. They cannot understand the full history of the machine beyond what they’re personally experiencing at that time. They conduct the needed maintenance in accordance with prescribed instructions. But meanwhile, this machine operates in a dynamic environment, coordinating its movements with other machines, talking to other machines, collecting and exchanging data with other machines.

With an AR overlay inside the Daqri helmet visor, the service person is able to ingest and interpret this multi-dimensional data to better predict the machine’s future health. “Machines today are increasingly incorporating data collection — from machine-to-machine communications and from the Internet of Things — data that could give the service person the ability to integrate the past to foresee the future, to look across similar systems in operation around the factory, the region, or the world, and to draw patterns from that,” said Buca.

Parker has been piloting four Daqri helmets over the past two years, working closely with the helmet’s maker on 10 applications, including Parker Tracking System and Remote Events, which help monitor the health of various machines. Buca says the Daqri helmet represents the “pinnacle of AR interfaces with capabilities to support our vision of the use of AR to create value in industrial markets.”

Above: Daqri’s smart helmet’s visor provides an AR overlay of real-time data.

Daqri unveiled its AR helmet at the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show and released a commercial version of it in March 2017. The units are priced at $15,000, and the company is initially targeting manufacturing and field services markets. According to its CEO Brian Mullins, Daqri will soon release an SDK for the helmets. A commercial version of its AR tech for glasses will be ready in June. Further, the company continues to offer an array of sensor packages designed to collect “very sensitive, real-time information for millions of workers in extreme thermal environments,” said Mullins, referring to hot and cold places where machines can go, but humans cannot.

The Los Angeles-based company is active in the burgeoning markets of AR wearables for automotive, manufacturing, and industrial applications, and in October 2016 it was reported to have raised $200 million in venture capital. Mullins declined to comment on the investment. Daqri recently hired Xbox cofounder Seamus Blackley to work on 3D printing technologies, which seems to fit into the company’s vision of developing new technologies for those workers whose jobs are most at risk from automation.

‘Technology doesn’t impress people’

Unlike a Silicon Valley executive who hopscotches from job to job, Buca has been at Parker for 37 years. The son of Italian immigrants, he grew up in Cleveland and oozes local pride. He’s quick to cite the area’s contributions to the invention of the light bulb (Cleveland was the first city in the world to have electric street lights, and Thomas Edison was an Ohioan), the global hydraulics industry (Parker), and health care (Cleveland Clinic).

But the region’s history of embracing new technologies can also leave the local workforce vulnerable to job losses from automation. A new report from MIT and Boston University economists for the first time quantified that robots were indeed taking jobs and causing a decline in wages. Such job loss was a powerful theme during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign and one that will grow in importance as, the conventional wisdom goes, every company becomes a tech company.

Above: Peter Buca is vice president of technology and innovation for Parker Hannifin’s Fluid Connectors Group.

Buca offers a slightly different view when I ask him about this. He doesn’t buy the idea the idea that new technology is somehow being sprinkled upon older companies like Silicon Valley fairy dust. “From our perspective, Parker has always been a ‘tech company.’ Most people, however, don’t consider all the technology used in every aspect of their existence,” said Buca. “In your question, ‘tech company’ seems to have the connotation of a software or electronics enterprise.”

“My perception is that we don’t differentiate ‘high tech’ from normal business in our region and — to some extent — may take for granted all the incredible technology that we create. We are very much a blue collar town and we carry our lunch boxes to construction sites, chemical laboratories, or hospitals,” said Buca. “The fact you’re interested in technology doesn’t impress people. Everybody is in technology.”

On the delicate topic of humans versus machines, Buca has a decidedly blue-collar perspective — meaning straightforward and practical. “The incredible productivity of today’s worker is made possible by the responsible and appropriate use of technology,” he said. “Humans are not the victims of technology, we are the beneficiaries of it. The important thing is to see the whole picture and understand that jobs are not being lost, they are changing. These changes are not just in the factory, but also in the office as we use technology everywhere to increase the power of the individual.”

Daqri’s Mullins takes a similar view on the issue. “We become so limited by this idea of technology replacing workers when the better idea is to power-up their senses and extend what they’re capable of doing,” said Mullins. The Daqri helmet “speaks to a future where a worker doesn’t have to be replaced by technology. The helmet will help people take on new roles and adapt.”

Above: “We become so limited by this idea of technology replacing workers when the better idea is to power-up their senses and extend what they’re capable of doing,” said Daqri CEO Brian Mullins.

The next century

For Buca and Parker, then, the requirement of a tech company being a silicon-based endeavor, depending on an app, or having been started in Silicon Valley is false. But as we’ll report in the weeks ahead, geography and perception can greatly affect an entrepreneur in the heartland’s access to capital and talent. We’ll see why companies are finding it makes sense to leave behind the high costs of say, Palo Alto, California, and decamp to Des Moines, Iowa, in order to be closer to their customers. “These are the markets that offer scale for growth,” Mullins said.

Whether it be an AR helmet, new polymers, or advanced conductors, Parker is bent on remaining a tech company. Buca circles back to my question of whether Parker has always been a tech company, or is it an example of every company becoming a tech company.

Above: Founded in 1917, Parker has grown to a global enterprise with approximately 50,000 employees, 400,000 customers, 800,000 products, and annual sales over $11 billion.

“Where companies may have begun their existence focusing on only a fraction of technology,” Buca said, “every company is growing to master many technologies to compete today and this trend will likely intensify in the future. That is a strong direction, and so I think the answer to your question is YES.”

The answer comes from a heritage that neither Facebook nor Google can lay claim to — yet.

This article debuts an occasional series, High Tech in the Heartland, that explores the relationship between Silicon Valley and the rest of America.