Watch all the Transform 2020 sessions on-demand here.

[Updated]

You’ll be forgiven for not having heard of Afiniti, a Washington, D.C. company that may be the first pure-play artificial intelligence company to file for an IPO since the big AI hype wave hit last year.

Afiniti uses AI to help companies more efficiently pair their sales people with customers, and boasts that it raises sales by an average of 4 to 6 percent.

Since Afiniti started 11 years ago it has lain low, preferring to amass customers quietly rather than banging the PR drum.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

About to go public

But now Afiniti’s about come under a spotlight. The company confidentially filed for an IPO late last year, VentureBeat has learned, and is valued at $1.6 billion after a fourth round of funding of $80 million that closed last week. It could go public as early as this fall, though that could change, sources close to the situation said.

In January, Bloomberg first reported that the company was considering going public.

We interviewed Afiniti’s founder and CEO, Zia Chishti, to learn more about the company. A January feature in the WSJ was the first and only in-depth look at the company we could find.

Chishti said he couldn’t comment about the company’s financials, citing SEC guidelines around IPOs. (Our sources said Afiniti will not be profitable this year, but expects to be in its fiscal 2018 year, which begins in June. Separately, Afiniti’s revenues are growing at a 100 percent run rate, the sources said.)

Pedigreed company

Chishti is already an accomplished entrepreneur, and he’s assembled all-stars on his board — directors and advisors who should impress Wall Street. Chishti previously cofounded and was founding CEO of Align Technology, a teeth-straightening device company now valued at almost $10 billion.

On the company’s board, Chishti has gathered names like Ivan Seidenfeld, former chairman and CEO of Verizon; John Snow, former U.S. Treasury secretary; and José Maria Aznar, former Prime Minster of Spain.

Investors in the latest round include GAM; McKinsey & Co; the Resource Group; G3 investments (run by Richard Gephardt); Elisabeth Murdoch; Sylvain Héfès; John Browne, former CEO of BP; Ivan Seidenfeld; and Larry Babbio, a former president of Verizon. The company has now raised more than $100 million, including the money previously raised, according to our sources.

Initially, Afiniti focused on serving large telecom and insurance companies that have sizable call centers, but then expanded to serve medical organizations and banks, Chishti said. Most recently, the company is targeting retail, where Afiniti says it can help match customers walking into a store with the most compatible sales person.

Overall, the company says customers using Afiniti for revenue generation see an average 4 to 6 percent revenue lift, and Chishti says he expects the long-term average will be about 4.5 percent.

How it works

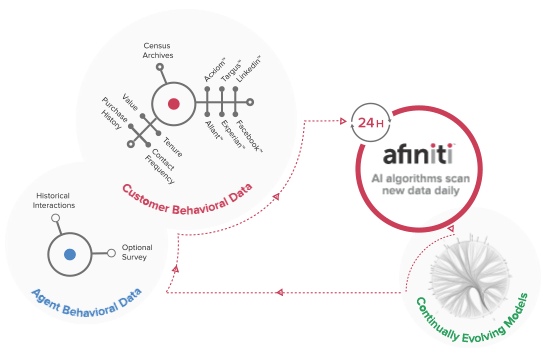

When a customer calls into a call center, Afiniti matches their phone number — either landline or cellphone — with any information tied to it from up to 100 databases. These databases carry purchase history, income, and other demographic information. They include credit firm Experian, data companies Acxiom, Targus, and Allant, social networks like Facebook and LinkedIn, and even census archives for info about the area the person is calling from. Afiniti then routes the call directly to an agent who has been determined, based on their own history, to be most effective in closing deals with customers who have similar characteristics.

Chishti is reluctant to provide actual cases of how the pairings happen, saying so many variables are at play that it’s hard to distill it to clear-cut examples. But, to simplify, a particular agent based in the Midwest might show particularly good results on calls with high-income moms from the same region, and so Afiniti would make the match.

The software continuously learns from a applying what is “basically a three-dimensional regression” on data about agents and customers, Chishti said.

For its service, Afiniti charges a fee that’s competitive with a customer’s alternative cost of acquisition. So, for example, a large telecom company might pay an average of $100 to $200 to acquire customers from other sources, say through ads on Google or door-to-door sales or direct mailing. In that case, Afiniti might charge an acquisition fee at the bottom of that range. Afiniti can also prove its service is effective by using a continuous on-off method: It runs its service for a period of time, say 15 minutes, and then shuts it off for five minutes, constantly comparing the number of sales its pairings are generating to the number made while Afiniti is off.

On its website, the company lists dozens of customers. Afiniti has already won every major North American telecom company, with one or two exceptions, our sources said.

In one example, Afiniti says it helped telecom giant T-Mobile generate $70 million in extra revenue in a year by optimizing 50 million annual calls. It did so by increasing telesales revenue by 5 percent, increasing retention by 5 percent, and reducing tech handle time by 2 percent.

When asked if there are any competitive companies that might serve as public or private comparables, Chishti says he can think of no one doing anything similar to what Afiniti is doing in AI. “We are somewhat unique in that we’re the only company that can precisely measure that impact [of AI],” he said.

Other companies say they use AI, but it’s often impossible to differentiate the impact of their AI technologies from other strategies the company is using to grow sales.

There are several other companies, like Pegasystems, that are also using AI and seeing fast growth, Chishti said. However, Pegasystems, like several other players, is more focused on informational retrieval technologies, optimizing how companies engage with and respond to customers.

[VentureBeat will take a closer look at these technologies at our MobileBeat event in July in SF, which is focused specifically on how AI and other personalization technologies are disrupting the larger marketing ecosystem.]

Of Afiniti’s 700 employees, 500 are engineers, said Chishti. Of those engineers, two-thirds work on client interfacing. The other third are AI engineers, split between business analytics and machine learning.

Of course, the company’s move into retail has big privacy implications. Afiniti wants to observe people at a store’s point of sale so that it can recognize them again when they come back. The company would use facial recognition technology, and the information would be tied with the person’s past shopping behavior and other data the system has tied to them. When the person enters the store, Afiniti would again pair them with the salesperson deemed a best fit to conclude a sale.

There are no laws prohibiting such technology, though for obvious reasons retail organizations may be shy to implement it. So far, Afiniti says no retailer is using the technology.