It’s been a week since the WannaCry ransomware attack began infecting computers running Windows software. And things are strangely silent again. It’s almost as if the wake-up call that WannaCry set off was heard by IT managers around the world — and then they hit the snooze button.

In a way, that’s not a bad thing. The cybersecurity community worked quickly and effectively to defuse the threat, while the kill switch demanded by digital kidnappers — Bitcoin payment — proved more difficult to manage than life without an infected computer.

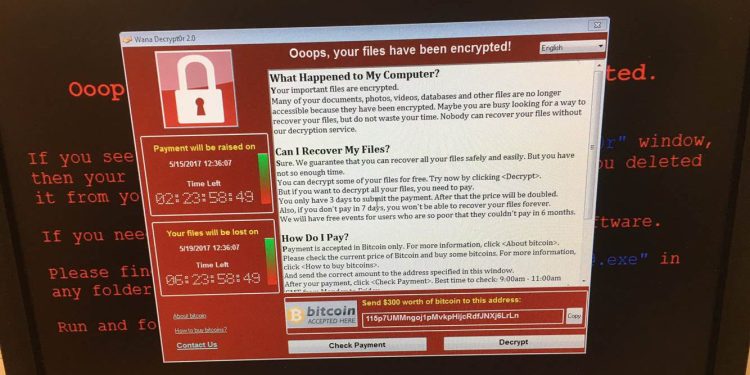

As of late Friday, after many of the deadlines threatening data deletion had passed, few victims had paid ransoms. According to Elliptic Enterprises, only about $94,000 worth of ransoms had been paid via Bitcoin, which works out to less than one in a thousand of the 300,000 victims who were reportedly affected by WannaCry. So we’re safe… right?

Looking back with the benefit of a week’s hindsight, two lessons are apparent.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

First, the story of the WannaCry attack is the stuff of cyberthrillers. Based on tools developed by the National Security Agency, WannaCry spread through phishing emails containing job offers, invoices, or security warnings. The malware infected as many as 300,000 computers, the vast majority of them using Windows 7 but apparently not running Windows Update, which might have otherwise installed a patch Microsoft created in March.

Infected computers ranged from those at companies like FedEx to systems in the hospitals of Britain’s National Health Service, raising the stakes of the attack from a corporate headache to a potentially life-and-death matter. Meanwhile, in a sleepy British seaside town, a 22-year-old researcher named Marcus Hutchins helped slow the malware’s spread early Saturday by discovering, and then registering, a domain name inside its code.

On Monday, reports of the ransomware caught fire. Stocks in the cybersecurity sector predictably spiked. Google Trends — a crude but useful measure — shows interest mounted on Monday, as the business world returned to work and booted up their PCs. It has since steadily declined, to the point that software security has once again becoming something of an afterthought. As the New York Times pointed out, many IT managers are calling the WannaCry hackers’ bluff.

That blithe spirit is bolstered by a vulnerability that researchers in France discovered and deployed to unlock computers infected with WannaCry (with caveats — victims can’t reboot their ill computers, and they can’t keep them running too long while infected.) That’s the good news. The overall response of the cybersecurity community has been strong enough to save many of the companies and organizations that had repeatedly dismissed previous wake-up calls.

Which brings us to the second lesson. While not as bad as feared, ransomware (not to mention cybersecurity threats in general) isn’t going away. Wired reported that the domain registered by Hutchins has been under intense denial-of-service attacks delivered by an army of IoT devices marshalled, zombie-like, by Mirai.

Mirai was the botnet that made news last fall by taking down sites like Spotify, Twitter, Reddit, and Netflix, thanks to unsecured IoT devices. So here’s Act II of this month’s cyberthriller: A highly effective hacking front is turning its efforts to free another semi-effective hacking initiative contained by the white-hat cybersecurity community. Fall back asleep, and this may quickly turn into a nightmare.

Malignant hacking campaigns are every bit as incremental as the software iterations being perfected by Facebook, that corporate entity headquartered on Hacker Way. Both set a mountaintop goal and both will charge back up again and again, no matter how many times it takes. Both learn, AI-like, by seeing what works and what doesn’t.

And now for Act III. The Hollywood narrative calls for the cybersecurity community to respond. How? (For starters, I’d suggest quashing the name cybersecurity — even “digital security” sounds better. Terms like “cyber” are so, um, 1990s). But that depends on two things. First, cybersecurity needs to take itself seriously. Sophos, for example, failed to update its antivirus software to block WannaCry until a few hours after the virus had infected clients, Reuters reported.

Second, IT managers have to stop putting off the inevitable when the inevitable involves a data breach that will affect a company’s technology, brand, and — above all — customers.

“I don’t want to sound alarmist, but I think we’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg — the number of cybersecurity incidents in coming years is going to multiply,” Dimitri Stiliadis told VentureBeat after his company, Aporeto, was one of several cloud security startups to receive funding this week. “The root cause is, if you think about how businesses develop software, security is often the last thing they want to think about because it’s not a revenue-generating function.”

If there’s anything we’ve learned in this past week, it’s that IT teams have seen security as an afterthought for too long. A lot of IT networks dodged a bullet, thanks in part to quick countermeasures from the digital-security community, but mostly because employees have learned not to bite on phishbait. WannaCry turned out to be a short-term sob fest. It’s up to corporate IT managers to make sure it doesn’t become an occasion for grieving.