With two riveting trailers, Sony has held us spellbound with the story for God of War. It introduced the first trailer last year at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3 2016), the big game trade show in Los Angeles. It didn’t ship that game yet, so it showed another trailer at E3 2017 last week.

In these trailers, we see a lot of violent action typical of the series. But we also see a lot of storytelling. Kratos, the angry god, has moved to Norse lands to escape the cycle of violence in his life. He has a son, and the mother is no longer around. The boy is clearly not a god, and Kratos appears contemptuous of him. But he is trying to exercise patience and hold back his anger to train the boy.

Last year’s trailer was an example of amazing storytelling. In the new trailer, the boy proves his worth in another way, by being able to communicate with the Norse beasts in their own language, while the Greek Kratos cannot. That changes the relationship of power between the boy and Kratos, and it makes for an amazing coming-of-age story that could very well widen the audience for God of War games.

Cory Barlog, creative director of the game, helped us parse the trailers and what Sony is willing to share about the story so far. The game comes out as a PlayStation 4 exclusive in the first quarter of 2018.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

I joined a small group session where Barlog answered questions about the game. Then I interviewed him one-on-one. I’ve combined the answers in this edited transcript of our interview. (And here’s a link to our interview from last year.)

Above: Cory Barlog, creative director at Sony Santa Monica studio on God of War.

Question: How open is this game?

Cory Barlog: The open world is a huge part of this game. It’s not an open world in the traditional sense where it has all these side missions and other sorts of things. It’s more that we have a very large world, and they have a goal that takes them all over the world, but always off in the distance there’s something that catches your eye. It’s this idea that we’ll reward people for being curious, for looking around. We’ll never put them in a position outside that core experience where we force them to do something. It’s more like, “I’m intrigued. What is that over there?” The idea of seeing this little cave entrance off in the distance, going inside the cave, and coming out the other end to see an entire level that you never knew was there.

That feeling of being rewarded for your curiosity is huge. It’s why I play games, this idea of truly existing in a world. I want to create something that feels like it embraces that idea. It doesn’t become a checklist. It’s not, “Oh my gosh, I gotta do these 20 things.” It’s, “Oh, this is so cool, did you find this place?” “No, I didn’t even know that was there!” We do that throughout the entire game.

The main narrative continues to open the world up more and more. We’ve gone with this methodology of guiding the player in the beginning, then opening it up, then opening it up even further. There are always these layers. Each time you reach a milestone in the narrative, there’s more to explore, more to the world than you knew. That, I think, is incredibly rewarding.

Question: Can you talk about the progression formula? Do Kratos and his son have similar progressions?

Barlog: We don’t have a lot we can talk about at this time, but we’re leaning a lot more into the idea that Kratos and his son having separate progression allows you to make choices not only with what you might do with Kratos — oh, I’ll spend this over here, make a bit of that Sophie’s choice — but also letting you play the way you want to play.

It’s this idea that I’m trying to hand power back over to the player. In previous games, everybody was familiar with the circle button that pops up over an enemy’s head when they reached a certain point. That was a very heavy-handed design element, the designer telling you, “You are allowed to do this now.” Which is cool, but as a player, I always think, “What if I don’t want to do that now?” I don’t want to always follow the same pattern. If you do want to follow that, great, but I want to put that decision into the hands of the player.

The circle button is always available for you as long as you have enough of your sort of Spartan rage. Now you can spend it. I give you the money and say, “Spend it wherever you want, but you have to earn it back once it’s gone.” Any time you want to do it — if you want to enter into a boss right and spend it right away, you can do that. You don’t have to wait. As I’ve seen games develop, I’ve seen play styles change, and that’s where people are leaning now. “Give me the tools and let me do what I want. Let me solve the problem the way I want to solve it, experience the combat the way I want to experience it.”

Question: What is the personality of Kratos’s child like?

Barlog: There’s a little bit of Rudy in him, that concept of always pushing and pushing and getting back up. This idea of my own childhood, feeling like my world was very small. Then, as I got older, the world seemed to expand a little, as I got to see more things and go farther away from home. This idea of a kid growing up in a tiny little forest and never being able to leave, and then suddenly getting thrown out onto the road with his dad, who he doesn’t know very well, to experience the world. You may see it as hostile and dangerous, but he looks at it like, “This is the greatest thing ever! What else am I going to do?” He hasn’t had anything to do until now, so this is truly the greatest adventure of his life.

Question: It seems like they’re both helping each other out.

Barlog: Yeah. The son is a the humanity that Kratos has lost. He’s that mirror reminding him that there is a different way, even if he forgot that way so long ago. Kratos is doing the best he can to help the kid understand what it is to be a god. There’s this internal struggle for him, because he doesn’t really want to tell the kid that. To him, that’s the worst thing in his life: being a god. When he found out about that, or even before he found out about it, it was this horrible change in his life. He’s almost trying to maintain the kid’s innocence, a bit. But he knows that eventually he’ll have to tell him. Then, how does he teach him? How does he teach his son not to make the mistakes he did?

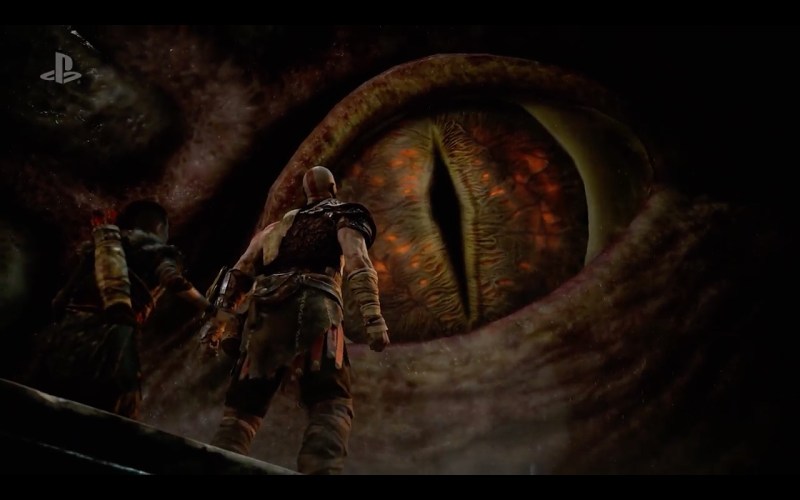

Above: God of War for PlayStation 4.

GamesBeat: There was one funny moment there with Sindri. Can you talk about throwing some humor into this game?

Barlog: The dynamics of storytelling are very important. To just be serious and morose all the time would be not very enjoyable. Bringing a tiny bit of levity throughout this experience — these are two characters who have very interesting and unique personalities. They’re very different from each other. They have, I think, incredible backstories, which get dug into a little bit, the things that make them who they are. They’re actually pulled directly from Norse myth. Brokkr and Sindri are two prominent figures.

Question: Atreus is the name of the son, right?

Barlog: Right, Atreus. The lineage behind that name — a lot of people are looking at that name and wondering what it means, trying to connect it back to Greek myth. The only thing I’ll say about that is that Kratos would never name his kid after a god or a hero. It’s a very personal name. The name means something. It gets explained in the game. But it’s something that means more to him than just, “This is a hero, a king.” That’s not it.

Question: You mentioned that this story is the most recent chronologically, but how far along are these events since the last game?

Barlog: At the end of God of War III, after laying waste to Olympus, Kratos leaves and, for me, goes on this really long wandering pilgrimage. A period of indeterminate time. We’re not giving any specific number of years, but it’s a long period in which he’s trying to isolate himself, believing that is not only what he deserves, but that it’s the way he’s going to fix things. He knows, at the end of that one, that he hasn’t resolved anything. He realizes he’s cursed. He’s going to live forever. No matter what he does, he can’t frickin’ die. That’s part of the torture he has to endure. But in order to endure that I think he realizes he needs to change.

During that period of time, that isolation, it eventually brings him to where we’re at now. There’s a period of time, even when he arrives in this area, that goes on for a while. We’re not going into that, because at the beginning of the game we sort of start late. We arrive at the scene late. An event has happened. The kid is at the age we’re seeing. Everyone is on the same footing. Old players and new players are all starting the game in the exact same place, where we’re not sure what’s going on. It gives everybody an on-ramp to this game. You don’t have to have played the previous games to enjoy this game, but if you have played those games, you simply have a bit more information about what’s going on. You’re still experiencing a similar experience.

Above: God of War

GamesBeat: You had a very interesting trailer again. It has gameplay action. But there’s a lot of story in the father-son relationship, too. What did you want to show this year?

Cory Barlog: My big thing this year — we are knee-deep in closing this thing out. We’re seeing the finish line come up. I wanted to give people a glimpse. We didn’t want to do a playable thing. That was too much at the time we were at. But I said, “Look, I still want to show people tons of stuff. I want to give a sense of the breadth of the world, but also touch on the journey they’re going on.” Without getting specific, because there’s a nice little story reveal that digs truly deep into it. I didn’t want to spoil anything.

What annoys me the most is I don’t want to know the whole experience. The best trailer I’ve seen to date is that one for Murder on the Orient Express. It’s so brilliant. They don’t tell you anything, but they tell you enough to make you think, “I want to see that.” People are clamoring for more and more, but then they say, “You showed me everything good!”

I wanted to show people that combat is fast and frenetic. It’s not just Kratos and his son walking around everywhere. But walking is a mode of travel.

GamesBeat: The thing I noticed is that there are these cinematic moments, and then there’s gameplay. The story is happening in the cinematics. But do you also have storytelling that comes through in gameplay?

Barlog: Yep. Even in little moments like — they’ll get in fights, and then afterward the kid will say, “Okay, how did I do?” And he says, “Not that great. This is why.” Then, in the next fight, he says, “Okay, how about this time?” “Still not great. Control your shots. Tighter groups. Don’t waste anything.” “Oooo-kay.” And then later on, “How’d I do?” “Adequate.” He has this nice little journey, even in just post-combat dialogue. As they go around on the boat and explore the world, there are opportunities to have those conversations you can’t have while you’re walking, too.

Story, to me, is happening at all times. The environment tells the story — sometimes literally, with writing on the wall. Or just simply with the architecture, or what you change in a room. They might have banter that’s relevant to something they just did, or a conversation they had a long time ago. Something the kid just can’t let go. All these fantastic road-trip moments.

GamesBeat: I did wonder how the kid would ever become useful to Kratos. Towards the end, though, it seems like he understands the Norse gods?

Barlog: He has a talent for languages. He was taught how to speak the local language by his mother. Kratos — again, pulled directly from me — he’s a little older, and he has a harder time learning a language. I can’t learn Swedish to save my life. I tried, but I’m not very good at it. The kid picks it up like nothing, though. He becomes the conduit for Kratos, which puts an interesting power dynamic in there. It switches things around. He’s this super-powerful god, but he can’t read the writing on the wall. He needs the kid. That becomes important.

GamesBeat: That gives you an interesting story to get into. Does the kid somehow lend some power in combat, though?

GamesBeat: That gives you an interesting story to get into. Does the kid somehow lend some power in combat, though?

Barlog: Oh, yeah. We’ve dedicated a button to the kid. In much the way a commander is ordering a soldier to fire — the kid is essentially Kratos’s soldier. He’s teaching the kid the ways of the world and how he’s going to survive in these fights. During a fight, the kid is autonomous. He has his own passive abilities that are either inherent or things that you upgrade and select for him. Then, every time you hit the kid button, he’ll fire wherever you’re aiming. It’s this great synthesis of the camera — with the new camera, wherever I look is the directive, and the button is the intent, the action. “I’m looking here. Do this.” If I’m looking at a door, I’m saying, “Go open the door.”

GamesBeat: The kid is your dog, kind of.

Barlog: [laughs] In some sort of very crude way, you could say that. He’s eager to learn. Like a lot of kids, he wants his dad to be impressed by him. He’s going to do everything he can. He’s like Rudy. Hit the ground, he’ll get right back up, because he wants to impress his dad. His dad is, in his mind, a superhero. Little does he know that Kratos really is a kind of crazy god.

GamesBeat: Earlier you mentioned how Kratos is of a mind to try to be less of a god of war. He wants to somehow make this work with his son, I guess? He wants to be kinder.

Barlog: He realizes he’s made a lot of bad choices in his life. He’s let a lot of circumstances dictate how he moves forward. He blames the past, blames yesterday, for the problems he has today. He’s at a point in his life where he knows that just pointing the finger at someone else because he feels they’ve done him wrong is solving nothing. It has solved nothing. Exacting revenge on those people also solved nothing. But the idea of having a son, for him — he’s cursed. He’s stuck. He’ll walk the earth forever. No matter what he does, he won’t die. He wants to find a way to do better, and a way to do better is to pass this on. He wants to figure out how to be better.

The journey for him, though — he’s not just going to become an altruistic paladin who’s going around and getting cats out of trees or anything like that. He’s still a very troubled man. The son brings a bit of that out of him. The son is a bit of humanity. He’s teaching Kratos what it is to be a human. Kratos is teaching him what it is to be a god. Both of them need each other. Together, they can make a whole person.

GamesBeat: Does Kratos have to worry about protecting his son in combat a lot?

Barlog: No. The high-level answer is that this is definitely not a protection-mission game. There is nothing about the son that is a burden. He is competent on his own. He’ll always hold his own on the battlefield. You can put him in situations of your own choosing where you say, “I’m sort of putting him at risk, because I want the related reward.” In those cases you enter into it with eyes wide open. But it’s definitely not a game where we’re trying to put the kid in danger all the time. I love games that have companions, but protecting them is my least favorite part of that. “Why did I die because of him?” That never happens here. You die because of you.