Watch all the Transform 2020 sessions on-demand here.

One of the hottest areas for VC investment at the moment is AI/machine learning — that includes artificial intelligence algorithms, related machine learning systems, neural networks, and back-end processing to produce insightful and self-learning applications. As Nvidia’s CEO recently said:

Software may be eating the world, but AI is going to eat software

AI investment at all time high

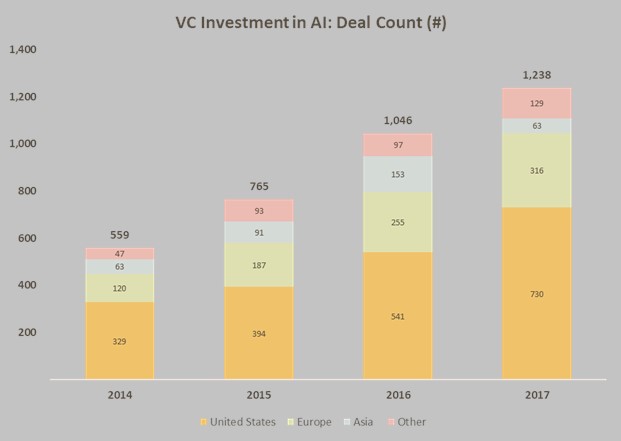

VC investment in AI has risen from $3.2 billion in 2014 to $9.5 billion for the first five months of 2017 annualized, with the number of funding rounds nearly doubling since 2015 to over 1,200 on an annualized basis so far this year. No wonder Frost & Sullivan calls AI the hottest investment trend of 2017:

But AI M&A is ‘small-deal M&A’

Investors piling into a space aim for multiple exits worth hundreds of millions of dollars. However, the pattern of AI exits is the opposite. Most successfully-exited AI companies sell for below $50 million after raising only a small amount of money. This works well for founders and small angel backers but not for VCs looking for exits well over $100 million.

Of 70 AI M&A deals since 2012, 75 percent sold below $50 million. These deals are often “acqui-hires” — companies acquired for talent not business performance. The number of $200 million+ deals barely registers.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Build a 10-20 person AI company, sell for $25-50 million

The typical journey goes like this: A small team comes together around 1-2 individuals, they forge real advances on key use cases (voice recognition, visual/video tracking, fraud detection, retail consumer behavior, etc.), sign a handful of prominent customers, raise less than $10 million (often less than $5 million), then attract the attention of a major buyer looking to solve that problem set. These kinds of AI companies are often valued as an amount paid per engineer rather than on performance (revenue, growth, profits); the average price per employee is around $2.5 million:

Even high value AI M&A targets don’t raise much

The other issue for VCs is that AI companies don’t generally need to raise much money, even if they are valued far above $100 million. Argo, valued at $1 billion for a majority stake by Ford, was 20 people when bought. Our research from PitchBook shows the 10 most valuable AI M&A targets raised on average only $15-25 million; there was only room for 1-2 VC investors in each deal:

Sure there are larger AI companies still growing, such as Palantir, valued at $10 billion having raised over $500 million. But a few isolated cases of $1 billion+ “unicorns” created using significant VC money is hardly fertile ground for 1,200 VC investment rounds. The reality is, AI just isn’t as rich a segment for VCs as investment activity suggests.

In fact, VC investment can be counter-productive

Once several VCs invest, an AI company can no longer entertain a $50-100 million M&A offer and must scale its team and product suite to ramp to a much higher valuation years further out; otherwise VCs cannot get the return they require. Here’s why we think this is counterproductive:

- The value of many AI companies is tied to three or fewer key technical leaders, who may not thrive in a scaling business. Often these are ex professors or deeply technical experts who can start to lose interest in a burgeoning and inevitably more bureaucratic company as it scales. The bigger an AI company gets, the greater the risk it will lose the 2-3 people who underpin its value. How do large buyers cope post M&A? They’ve learned to take great care to shield these technical geniuses from internal bureaucracy, much harder when they are founders of a rapidly scaling company and are expected to have input on many key actions.

- Many buyers view the ‘scaling’ of sales, marketing, and business development functions as a NEGATIVE to value. They want the technical team and the core algorithms and IP and have more than enough commercial talent in house. They don’t want to pay extra for people they will let go.

- Raising VC money to scale an AI business forces its M&A valuation beyond a $50-$100 million “tactical buy” and into a larger “strategic bet.” Buyers must think carefully about this larger bet, and this creates more risk a buyer will waver on a deal.

- For VCs, this investment profile often does not make sense. Investing in AI can mean writing a small check for a brief time to get a very good but not stellar return. VCs want the opposite — to put more money to work for 5+ years and get 10x their money back. It’s the difference between playing Blackjack and Go, AI M&A is often the former, VCs always aim for the latter.

- Technical founders often don’t net any more money after raising VC money. For example, raising $5 million and selling for $50 million can be far more lucrative for technical founders than raising say $25 million and selling for 100 million. So why should they go through the whole process?

For many AI founders, the best approach is raising little money, demonstrating they can solve hard problems, and waiting for the M&A phone to ring.

For VCs the best approach is often to look elsewhere.

Victor Basta is founder of Magister Advisors, a specialist bank focused on M&A exits and larger financing rounds.