Games lead the way when it comes to exploiting new technologies, and that’s why we had a panel about games and artificial intelligence at our MobileBeat 2017 conference in San Francisco this week.

Game creators have used A.I. for decades to control non-player characters, who have evolved from incredibly stupid (bumping into walls) to the moderately stupid (unable to utter more than a few responses). And game marketers are using A.I. to target the right users with more sophisticated ads that have a greater chance of getting a proper reaction from players in mobile games.

We recruited a panel of both gamemakers and marketers to help us predict the future of A.I. in games and how both game design and game marketing are coming together to provide a better overall experience, improved retention, and higher monetization in games. I moderated the session, and our panelists included Margaret Wallace, the CEO of Playmatics; Brandon Wirtz, the CEO of Recognant; Kabir Mathur, the head of business development at Kiip; and Adam Fletcher, the CEO of Gyroscope.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: Am I a robot?

GamesBeat: We have a very broad topic here. I’ve split it into two different categories. On the one hand, A.I. has been used in games for a very long time to simulate human behavior and provide computer opponents. That’s where gaming’s expertise in A.I. has come from. Recent advances in A.I. are going to impact the way people play games in a very big way in the future.

Respecting the fact that we’re at MobileBeat, though, there’s another part of the conversation here, about how A.I. can take the dumb and blunt marketing we have today and turn it into smart, more targeted marketing in games and other apps. The marketing-speak of the last few years has suggested that our mobile marketing companies are delivering smart targeting, analytics, and responsive marketing, but we’ve barely scratched the surface as far as using A.I. to improve the monetization of users. We’re going to talk about both of these sides, from the point of view of game designers and game marketers.

First, please introduce yourselves.

Margaret Wallace: I’m the co-founder and CEO of a company called Playmatics. I’ve been in the game industry since 1996, which in cat years is just ridiculous. I’ve found that even in terms of artificial intelligence and things like machine learning and customization, games have always been at the forefront of exploring this territory. We’ve led the way, but we’re often the odd people out at some of these larger conferences. I’m excited to chat with you about the work we’ve done.

Brandon Wirtz: I’ve been a consultant to video game companies going on almost 30 years, and I’m not yet 40. This is primarily in the A.I. space. I was very early into chess engines. I built one of the first bots for playing multiplayer against a computer, those kinds of things. Today I’m the CEO of a company called Recognant. It’s one of the first multipurpose A.I. companies, doing both numeric A.I. and heuristic A.I.

Kabir Mathur: I’m the head of business development at Kiip. I’ve been in the mobile gaming space for about a decade now. Kiip is a differentiated form of advertising for mobile. Instead of just showing you an ad for something, we meet you during moments of achievement, like leveling up in a game or finishing a workout in a fitness app. We work with Fortune 500 companies to reward you with something tangible, or of virtual value, within those specific moments.

Adam Fletcher: I’m the CEO and co-founder of Gyroscope Software. We offer personalization services via machine learning for mobile apps and games via a Unity plug-in. I’ve built games on my own for a long time, but my background is more in systems programming and approaching A.I. as a sustained effort.

GamesBeat: We can delve a bit into history here, talking about A.I. in games a bit. We all remember games where the A.I. was so dumb that non-player characters kept running into walls. Margaret, can you take us back a bit?

Wallace: I was fortunate, at the start of my career in the game industry, to be presented with the world of how A.I. is used within games pretty early on, using two very striking examples. One was a product called Petz. They were dogs and cats, some of the first ever virtual pets. I worked with a bunch of A.I. programmers and behavioralists to create that engine. Then, when I was working for a game publisher, I had a chance to interact with another A.I.-driven pet experience called Creatures.

The difference between the two, besides the names, was that Petz took the approach of using A.I. in a sort of Disney-like fashion. It was about building a character and an experience. Creatures tried to use the science of A.I. to create creatures based around evolution. They tried to mimic real, non-cartoon-style cryptids with artificial intelligence. I learned a lot about things around the use of, at first, scripted A.I. and how that can be used in game design, but also adaptive A.I., which is where we’re heading a lot more now.

Fast forward to the present day. I said earlier that games are sort of the odd man out, but we’ve seen games infiltrate just about every industry sector as far as applying the things we’ve learned around A.I. and machine learning to areas like banking, ecosystems, scientific research. It’s been interesting to see that evolution, seeing things we’ve learned in games applied in multiple industry sectors.

Wirtz: There’s a lot of different types of A.I.s in games, in terms of just the methodology. Who here has played tic-tac-toe? Who here could beat a four-year-old at tic-tac-toe? Okay. These days, programmers in high school are learning how to build a tic-tac-toe engine, because there are only so many possible moves. There’s a kind of A.I. that simply calculates all the possible moves in advance and wins because it has more computing power than the human brain. Or it can memorize more things than the human brain.

Then you have chess engines that can go through and say, “This person is playing with this style. Let’s change up, because we know that if we see this opening move, they’re playing aggressively and we should switch to a defensive strategy to counter.” And you have first-person shooter A.I.s that ride along a little rail, and if its vision vectors see something, they turn and shoot at it. These are all different types of A.I.s.

Above: Forza 5’s damage engine is entertaining to witness, but clean driving will benefit your Drivatar best.

What’s interesting now is we’re starting to see some A.I.s that are driven by language and things like that. You have A.I.s that can play a game like Mass Effect and go through the storyline. They can’t actually map out every choice you’re ever going to make, but they say, “You were flirting with this character. Maybe this character should be your love interest,” as opposed to just doing the choose-your-own-adventure thing from the ‘80s where all of the routes were pre-calculated. We’re starting to hit the cusp of seeing real interactions with A.I.

The last type of A.I. is this weird pseudo-A.I. we see in things like Microsoft’s Drivatars. It’ll watch how you do a thing and think, “Okay, I’ll do that thing the same wrong way you did. This person always steers off the center of the racing line, so I’ll do that. He always turns toward a car as he goes by, so I’ll do that.” You pick a couple of nuances and create this immersive fake experience.

These are not A.I.s that will learn to take over the world. There was a story about a guy who left his Quake III bot on for four years and they discerned that you shouldn’t shoot each other and peace was the way to win. Of course it turned out to be fake, but we’re not getting there because most A.I. in games is not neural network or true learning.

GamesBeat: Something about the Drivatars, too, from the Forza Motorsport games — that came out in 2013, along with the Xbox One console. The model of computing they used was to offload that A.I. computing to the cloud so as to add the Drivatar enhancements to the game. That balance between console processing and the cloud was interesting. Now it’s 2017, and seems like we can start thinking about doing some of this on the device, using just that processing power. Is there an advantage to going in that direction?

Wirtz: We all use Siri or the equivalent of Siri. Apple spends more on hosting the backend of Siri than they paid to acquire Siri from Adam Cheyer a number of years ago. Hosting is so expensive, and you need that uptime for the life of the game. If you want the game to run for seven years or however long, you have to maintain those A.I. servers for however long. It’s no fun if you can’t pop in your old games and play because the online component’s no longer there.

GamesBeat: This seems like a good segue into what you’re doing at Recognant.

Wirtz: Recognant is focused on a couple of things, but primarily moving the ability to do natural language processing and real virtual experiences where you’re communicating verbally onto the cell phone or the mobile console, so you don’t have to have this always-on connection. But you can also do things like have a non-player character where you walk up and say, “Hey, bartender, where’s the nearest weapon shop? What do you know about the troll over there?” You can ask those kinds of questions, and if it’s not in her sphere of information, she can say things like, “I’m a bartender, I don’t know anything about weapons.” But if you go to the bar owner he’ll say something like, “Sure, I buy all my weapons at this place,” and give a different answer based on those sorts of things. You can have real dialogue that isn’t scripted.

Above: Margaret Wallace, CEO of Playmatics, talks about the future of A.I. in game design.

GamesBeat: That’s an interesting direction for things to go. It brings in this idea of A.I. for promotion and marketing. Kabir, when you hear about something like that — you could have the bartender answer some questions in a way that promotes monetization or retention. From your point of view, on this side, can you talk about the potential of what A.I. can do?

Mathur: Having the bartender say something specific is out of the scope of what an ad network can potentially do. But there are a lot of analytics tools and out-of-the-box tools that allow for personalization. What we’ve noticed, working with thousands of game developers, is that everyone is trying to funnel all their users through the same experience. This is very similar to the way ad networks think about user funneling. You’re trying to get a user from point A to point B as efficiently as possible and get as many of them as you can through the funnel, which is similar to how a game works. You have a tutorial and you have levels, and you want as many users as possible to go through that process, hopefully making a purchase along the way.

What we recommend—we work with these personalization technologies and deploy them with several different variations of content to appeal to different segments of users. The ultimate objective is to have an experience that’s tailored down to the individual user level. Andrew Wilson at Electronic Arts just spoke about something very similar a month ago, where he said that they want to move into user-based narratives. Every user will have their own narrative and you’ll never have to play the same thing twice.

That’s a pipe dream for most developers, perhaps, because they just don’t have the budgets, but these out-of-the-box technologies I’m referring to will, in combination with things like Facebook Connect, know enough about a user to where you can say, “This user is from this location. This is their approximate age range. This is their gender. I know I can deploy this type of content for them, and it might be more effective than this other type of content that might work better for, say, a woman aged 35, as opposed to a man aged 18.” You can deploy five or 10 different experiences, A/B test against different segments, and choose which ones to deploy to which user, the best available that you can predict.

Fletcher: One of the things my company is trying to do is to bring that specific user personalization to any mobile developer. The reason you see EA doing that now, or Amazon, is because they have the data. But there’s this idea about the unreasonable effectiveness of data in A.I., getting enough data to be able to make decisions. We want to provide developers a solution where we have all that data, and once we have that data it’s actually the same techniques you would use for segmenting. You can just apply them on a per-user basis. You get to say things like—if I’ve watched this player go through these events, maybe thousands or tens of thousands of events, that can then trigger the bartender to say, “Hey, I happen to be dating the blacksmith’s son, if you buy these gems I can get you a discount.” It becomes an integrated IAP prompt.

What we’re working on is the control points in that process. “Trigger the IAP prompt now. This is the time when this person is receptive to that.” And that’s by watching all of that data stream come in and saying, “Trust the machine to figure that out.” That’s the approach we’re taking to bringing in that level of personalization.

Above: Richard Bartle of the University of Essex hypothesized about why people quit games.

GamesBeat: A.I. helps us feel that a game is personalized in some way. That’s both on the marketing side, where the game is trying to sell us something, and on the gameplay or narrative sides, where the game is just trying to keep us engaged and playing along in a way that feels natural and enjoyable. But it seems like there’s a problem with personalization.

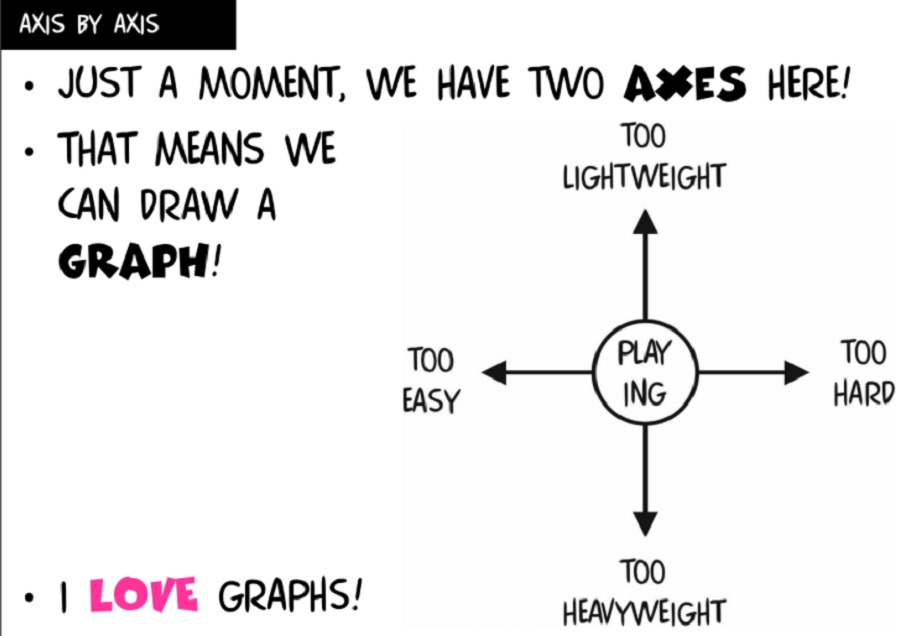

Richard Bartle, a well-known professor who’s studied games, gave a talk recently in Barcelona at the Game Lab event talking about how the problem is that every gamer is different. If you’re trying to design a game’s A.I. so that it isn’t too easy to play against, nor too hard, that’s important for retention, but you never know where the line between too easy and too hard really is. How do you guys think about that problem?

Wallace: I think about that a lot in the context of game design, just trying to differentiate a bit from the rest of this discussion as far as our focus. At Playmatics, we’re a small startup. We work with all kinds of folks with different capacities and resources. We all know where we want to go with things like A.I. and machine learning, and sometimes we can go there depending on what we have to work with, but sometimes we can’t. Just because you have the ability to leverage A.I. or machine learning in a game experience doesn’t necessarily work out on a pure one-to-one transactional basis. It could actually be a demotivational experience.

For example, I’m working on a project right now involving A.I. in a scavenger-hunt mechanic. It’s an app that already exists. My first experience with the app, beyond the registration, was discovering that the A.I. has context-sensitive mapping to tell me what objects are near me, but the first object it served up was so incredibly rare that finding it would be an impossible task right out of the gate. It was very demotivating for me, even as someone who was very motivated to engage with the app at the start.

That speaks to things like personalization – understanding player style and practices. It speaks to issues of onboarding, and making sure that if you’re going to apply an A.I. mechanism to an experience, you really need to test it out with different use cases. How many of us have been served a memory on Facebook that you don’t want to be reminded of? That’s not a good user experience. To me that’s a prime example of A.I. going wrong, or algorithms not being tested out for everyone’s use case.

Wirtz: There’s a thing in storytelling that also applies to gameplay, called the storyteller’s curve. If you watch Star Wars, it opens with this big, exciting scene, very high drama, and then it settles down so you can rest for a while and have a contrast with more drama later on. If you’re in a driving game and racing Laguna Seca, it works the same way: a straightaway into a curve, then it ramps up the excitement level. And then the A.I. in Left 4 Dead did this with its zombies. They’d say, “Oh, we’re going to herd you and chase you and then something will jump out of somewhere at the climax.” It builds up that big fright by making you run, and as soon as you think you might be safe, bang, all the zombies come out, because it’s monitoring what your controller is doing and all this other stuff.

That A.I. is driving the experience in a way that’s not necessarily personal to you, but it reacts to what you do in a way that feels personalized. Your health just dropped to 15 percent, so let’s give you a chance to catch back up so you don’t just die right away. You feel like you’re reaching achievements along this curve. That’s a big part of what A.I. in storytelling is doing right now.

Above: Margaret Wallace, CEO of Playmatics, speaks at MobileBeat 2017 panel on game A.I.

GamesBeat: Do you think that covers enough different types of behavior from players?

Wirtz: The nice thing about some of those scenarios is that a well-developed one looks at multiple types of milestones. What’s your incentive? What’s your “achievement”? You might be playing Skyrim in a way such that it’s “How much of the map can I see?” So maybe it should give you a quest that shows you more of the map, because that’s what you’re in the process of doing anyway. That’ll pique your interest. You can balance between those things. Maybe it seems like you’re really into exploring the landscape, so it’ll send you to find this particular plant that’s really hard to find, a detail-oriented thing. The idea is to find what sort of excitement is good for that user, so you can keep them on that storyteller’s curve.

GamesBeat: When it comes to personalization on the ad side, Kabir, what do you think about how personal this can get and how personal it should be?

Mathur: I think from a content perspective, personalization can be thought of as a spectrum. On one side of the spectrum you have the EAs and Ubisofts and Kings of the world, which can push users from one property to another across a huge portfolio, and also have the resources to hire huge data science teams. They could actually deploy personalization models down to the user level if they wanted. And on the other side you have indie developers, who have neither the resources nor the data scientists to accomplish any of that.

Somewhere in the middle you have smaller game companies – Storm8 comes to mind – who have built up network effects really well. They have a portfolio of dozens of games with well-developed mechanics to push users from one game to another. They have a rich data set of user actions. They know when user A moves from this game to that game. They’ve learned a lot about the preferences of that user. They can deploy certain content personalization strategies that are going to appeal to that user.

What I think game developers on the smaller side of the spectrum need to think about—you have to learn something about your users. Build a connection with these people and use it. Figure out who your users are. Even if you’re only deploying three or four models based on basic things like age, gender, and education, that’s better than pushing everyone through the same content pipeline. There’s a lot of variables you can test. There are push notifications, in-game messaging, iOS versus Android. iOS users tend to be better-off than Android, so maybe your first IAP offer there should be of higher value. If Android users are less likely to monetize, maybe you can show them more ads. There are lots of models you can deploy.

Fletcher: It’s critical to understand your users, no matter what. That’s critical from the standpoint of narrative development all the way to understanding the LTV of your user base. Personalization, what A.I. brings, what I want it to bring at least—as someone who plays a lot of games, I want to have fun. I’m here to play games and enjoy myself. I recognize there’s a balance between creative needs and business needs, and I think A.I. can successfully balance those two things.

I started a game yesterday where I got through about 15 seconds of content before I ran into a minute and a half of ads. I never played it again. That game is dead to me. But there was an opportunity for that game to have a much better personalized experience by showing me the right amount of ads, or possibly sending the right level of IAP prompts, and yet still keeping the enjoyment level high.

The comment about being able to move gamers between your properties, if you’re a big enough publisher or studio, is valid. You’re continuing a sort of meta-cycle of fun there. The advertisements you see there are trying to draw you into the next game and so on. King and other companies are very good at that. But the critical issue is simply to keep people having fun. We’re making games. A.I. will help that happen. It’ll lead to a better experience for the user balanced with LTV for the developer.

Wirtz: There’s a big lesson between what the two of you pointed out. You said, “Here’s the very sparse data from which you can make decisions.” That’s a very important thing. Then Adam’s company says, “Here is a metric ton of data that may be overwhelming, so you have to know where you are on the spectrum to know how to use it.”

Above: Gyroscope uses A.I. to improve engagement in games.

GamesBeat: Adam, can you tell us in some more detail about what your company is doing?

Fletcher: What Gyroscope is doing is we’re gathering a whole bunch of data points that are passively instrumented in the game. They don’t represent specific user attributes in the sense of what we’re talking about here – we don’t actually care about stuff like demographic data. We’re watching interaction data and we’re watching a lot of it. From that, we feed it into a machine that learns when to trigger actions in the app or in the game.

The key here is that with the unreasonable effectiveness of data, the machine doesn’t care. It doesn’t care about your gender or anything else like that. It just evaluates a stream of events, makes decisions based on that, and acts in the game. Our models let us do this in ways that are effective as far as IAP prompting, changing up the random number generator to create a better experience, really any action that can take place in the game.

You’re right that we are very much taking a data-first approach to this. We’re gathering tons of data. Our customers often ask, “Hey, can we see that data?” and they can, but it’s not really human-interpretable. It doesn’t tell you something like a business function. It doesn’t tell you how people are getting to where they’re going, and that’s okay. We’re not designing around that. We’re designing around retention and engagement, not necessarily acquisition.

Wallace: One area I’ve been working in is pretty interesting that uses A.I. and machine learning. I was working with the Scripps Research Institute to build the equivalent of a web portal, something like Kongregate, for citizen science games, called Science Game Lab. What we’re building toward is using human computation across a variety of citizen science games, games that drive research. They’re not just educational, but actually part of data-driven research, using human computation as a basis for building more sophisticated machine learning. A lot of what we’re doing is built on principles we’ve worked around in gaming for years, a lot of those stepping stones.

GamesBeat: I’m curious how much you all think the two different conversations here come together into one conversation. We have A.I. for marketing and A.I. for game design. It seems like in this area of why people drop out, why people stop playing a game, these two areas come together. You might apply science from one side to solve the problems of the other.

As far as dropping out goes, some people might think they’ve run out of content. In a situation where the content is procedural, where it’s constantly being generated, it might still eventually feel like the same type of thing every time. When a game turns into a grind, it feels like there’s no point in continuing.

Wirtz: The big guys are doing a lot of things where they ask, “When do I drop the DLC? When do I push somebody into the next purchase?” But you also see that in the mobile space. I play this game called Hill Climb Racing 2 from Fingersoft. Every time I lose badly enough, it hits me with, “You should buy the upgrades! Look, for a dollar you can buy some stuff to make your car go faster!” It has hit me more times than I’d care to admit for a game that I wouldn’t have paid four dollars for up front. I’m getting nickel-and-dimed by these pay-to-win purchases.

Fletcher: The content space is a really interesting issue. How many of us were excited for No Man’s Sky? It looked awesome, and now it’s the best way to take photos of a game you never play. It’s too bad, because it’s such a great basic idea. But there was too much content, no narrative, nothing compelling you to move on.

Above: Artificial intelligence

GamesBeat: It was all A.I.-generated, procedurally-generated play.

Fletcher: That’s a risk. That’s a risk on the personalization side. Let’s say we’re really successful at figuring out what you want and we just feed you those pellets over and over again. We’ve moved on from creating a game at that point and now we’re just conditioning you. That’s not what we want. That doesn’t help anything.

GamesBeat: Except for in the gambling business.

Fletcher: Exactly. You see a lot of companies pivot in that direction eventually, into mobile casino. But if you look at most of games, the active user count at 30 days is maybe one percent of the original peak count. A good seven-day user count is 20 percent of the original. That’s a big number on mobile. So it’s very hard. It’s like running a website. The continuous stream of content is key.

Wirtz: There have been some games where the whole point was that the A.I. was just flaky. The Sims was basically just, “Hey, how can I get these weird ants to do weird things?” There was infinite content because you could game the infinite number of A.I. variations.

Wallace: That’s another kind of gamer strategy that people don’t think about very much, but it’s a part of design. There are types of players who like to break an A.I. I was just playing with Wolfram Alpha and having fun trying to break its logic. Even when I worked on virtual pets, a large portion of our audience wanted to hack into the game files and make dogs out of the cats and pigs out of the dogs. We let them keep doing that because it created a more devoted committee around the game.

GamesBeat: Kabir, you actually offer rewards to players for different things. What is the best time to offer that? Is it at that point where you think the player might be about to drop off?

Mathur: It depends. We as a network have the luxury of having access to a lot of player data. We’ve seen them in not only one game, but in a dozen games, potentially. We know when the user is most likely to respond to a reward. As a network we’re a little different from other ad networks in that we’re not just trying to deliver as many ad impressions as possible. We actually looked past the opportunity to deliver impressions in order to build a premium network. That’s how we can charge premier prices. It’s also a reason lot of our customers work with us, because we can actually drive retention and drive engagement.

We have our own kind of taxonomy around different moments. You have winning moments and losing moments and other instances you can potentially reach the player. Most advertisers want to reach players during up moments, but we have some particular cases where they want to reach people and boost them during losing moments. We can choose when to show that specific reward to people at a down point in their gameplay. That’s how we think about it.

To your earlier question, the game design funnel and the marketing funnel are going to start to merge, at least toward the top of the game design funnel. Everything from showing the user their first impression of your game, to try and get them hooked—that’s very important. Game developers want to work with networks that have very sophisticated testing functionality.

It’s not just about A/B testing for different creatives and saying, “Okay, this one has the highest clickthrough rate, so I’m going to deploy it.” Networks now are going to be able to deploy creatives that are customized down to the color of buttons. All kinds of things can be different depending on the user base because we have access to such large data sets. Work with a network like that, so a user has the best first impression, the most accurate impression of your game. Then they go through the network’s funnel, download your game, get through your tutorial, and that’s where the content strategies we were talking about earlier come into play.

That’s where the two converge. Further on down the funnel, networks don’t have as much effect on retention and things like that. That’s where we can step out of the picture.

Above: The Terminator

Question: Where do you see neural networks having a place in gameplay and game design?

Wirtz: I’m horribly biased, but neural networks aren’t new. They’re 65 years old. We haven’t really made any improvements since then. The processing has gotten up there. There’s always been this challenge where—flight simulators were some of the first ones, Wing Commander and all of those things. Developers had to decide whether they wanted to spend their cycles on A.I., or on physics, or on graphics.

We’re not in a place on the curve yet where we have enough GPU to take a neural-network-powered A.I. and combine it with 4K-per-eye VR. The neural network isn’t really ready for a lot of this stuff. It is for marketing. Adam is ready to do neural networks, tension flow, those kinds of things for advertising, because he doesn’t have to render graphics while he’s doing it.

Fletcher: I do think there’s a hybrid model there, in terms of the Drivatar aspect of things, towards what you can do with RNs and things like that. You’re continuously feeding a learning network live to a backend through a service like Xbox Live. You’re developing an A.I. for games there, and it then pushes the model back to the player so the A.I. does improve and matches the player better. Just as AlphaGo got better and better, I think we can now target players to a difficulty level that helps them learn or helps them find a challenging and fun narrative. But I agree that on a GPU, if you’re rendering graphics as well, that’s just going to be too difficult.

Question: How do we look at the data going through hardware devices to then match that to the types of games we’re building? Not just software data, but hardware data.

Fletcher: We obviously use software data to do what we do. We don’t use any hardware data.

Wirtz: Microsoft, on Xbox, for Forza and a couple of the Unreal engine games, would do things to make sure that they had profiled things correctly. When you deploy across Xbox, it looks like one piece of hardware from the outside, but there are really maybe six variations. You find out that Skyrim crawls to maybe four frames per second in a dragon fight scene and nobody wants to play that. So they do do some things where they take feedback from the hardware. What’s the framerate? What’s the load? Is it because something’s running in the background on the Xbox? I don’t know that anyone is necessarily applying machine learning to that afterward, but in some cases that data is being gathered from users.

Mathur: We don’t influence game design, but from an ad-serving perspective, looking at hardware attributes is very important for us. Which OS version? Which OS? Which model? These are all leading indicators for us of what type of user we’re dealing with. That information, combined with their location and age and other things like that, helps us figure out who this person is. Are they going to buy something that’s of high value? Should we be showing them ads for BMWs and Mercedes? That’s all very valuable to us.

Above: Artificial intelligence has a big future in games.

GamesBeat: You talked about different types of creative and their component parts. You maybe create 10 different ads, componentize them, and then assemble an ad for a particular user to see. Where are we on that right now? Is that the state of the art right now?

Mathur: The short answer is no. I can tell you that when I log in to Facebook or search on Google, I still see irrelevant ads. And they have more than a million advertisers. But I think huge strides have been made over the last couple of years. Data science specialists have made a lot of progress on that front. There are companies you can license technology from. That’s what we’re doing. We’re not building this technology in house. We’re licensing it. Basically, we can deploy 500 different creatives rather than just five. We’re not putting the onus on the advertiser to develop each of these, because who wants to spend time on that? We can take the component parts and deploy them using machine learning with both first-party and third-party data sources. So we’re not quite there yet, but huge strides have been made.

Fletcher: When you work with someone who’s qualified, they already know that—your call to action button could say, “Get it now,” “Buy now,” “Click here,” all these other things. They have a list of 40 different things that could appear on that button. That’s how you get to these really large numbers of combinations that you can optimize for.

Question: From your side, working on the gaming A.I. aspect, do you see that supporting native ads or pushing more toward the mobile web?

Wallace: For us it’s a business decision. It really comes down to our content strategy and the partner.

Wirtz: A.I. in gaming is so many different things. It’s everything from level testing to the ad space. I don’t think that A.I. is going to determine whether advertising is native or mobile or whichever startup it was that was going to put GPUs in the cloud and work over remote desktop, that kind of thing.

Wallace: You’re touching on an important thing, though, which is that if you’re going to use A.I., you’re going to be very device-specific. Look toward the things that make that device special and use your A.I. to drive that feature, because that’s a real differentiator that isn’t often explored. Everyone has the capacity to do that.