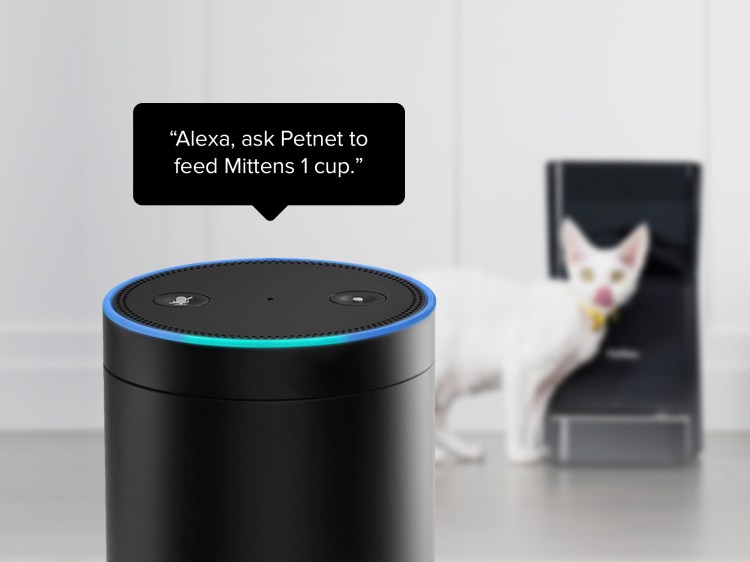

By now you are probably talking to machines more often than you are to your neighbors, your old college friends, or even your mom. Voice interfaces are everywhere. We put an Amazon Echo or Google Home in our kitchens and they quickly became part of our morning routine. We talk to Siri to find a good movie to watch. We search, send messages, control our connected devices, and we shop — all by voice. For brands and marketers, this provides a unique opportunity to converse directly with consumers, however, it’s not as easy as it may appear to be.

There is a reason voice interfaces, quirky and novel only a few years ago, are seeing such speedy adoption. They adapt to human behavior better than the interfaces that came before them, which include the GUI and a mouse, the Touch UI and our fingers. Now it’s the Conversational UI and voice. With each advancement of the human-to-machine interface, we got better at making the interaction more human. And, as you might expect, marketers jumped at this opportunity.

Our kids “get it” first. When the iPad debuted in 2010, kids quickly figured out how to use it by swiping the screen. But swiping a printed magazine didn’t work. They expected the rest of the world to work like the iPad, but all they got was a broken interface. Voice UI is following a similar pattern. In no time at all, our kids are talking to the machines. But when they say “Alexa, open the car window,” or “Google, fix the TV signal” nothing happens. As with the iPad, they are waiting for the world to catch up to them. As much as a mouse and touch were the interfaces of adults, voice is the one kids will know best.

Voice UI is big, and it will only get bigger as technology advances. We’ve already built a ton of Alexa skills, Google Home actions, and Siri extensions. And we are actually getting really good at explicit interactions, like: “Alexa, how long is my commute this morning?” or “Ok Google, tell me the weather.” Life is great, right? Not quite. We love to talk to our bots, but we abandon them quickly. According to VoiceLabs, there is only a 3 percent chance a person will continue to use a Google Home Action after the first week. That’s not a good statistic if you are a brand marketer trying to build one-to-one interactions with customers. Also, building more complex interactions that go beyond a simple coordination is very hard.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

So, why is that? For the most part, we are not creating conversations, we are building old-school commands hidden behind voice requests. These work well when we want to add something to a to-do list, play a song, or set an alarm to wake us up the next morning. Clear and deterministic. But these fail when there is more room for ambiguity. More complex interactions require collaboration, not just coordination. For example, I would like to talk to my virtual assistant on Saturday morning and decide what to do that weekend. I have a goal — a fun weekend — but not a clear way to achieve it. My assistant and I should be able to have a quick chat and together decide what to do. Additionally, it should already know me pretty well from previous conversations. It should know my preferences, aversions, and what I can sometimes be talked into.

Designing conversations is not new. Conversation theorist Paul Pangaro is probably the front-most authority. The architecture he proposes defines simple elements and flow of a conversation. In this model, participants share a common context and language. They define goals and evaluate and exchange information repeatedly until they reach an agreement. Concise and simple design. Perfect as a building block for creating better Conversational UI.

Currently, some of the best tools for creating conversations are PullString and Dexter. They try to present a friendly interface to writers while still remaining flexible and powerful for developers. But to create better interfaces we need to evolve these tools by, for example, extracting the business logic from the conversation layer to create a human-first tool — a writer’s tool. This would be a distraction-free interface where a writer can concentrate on the art of conversation and at the same time offer an AI-augmented interface for developers, where logic is partially inferred from what the writer writes. Both could be aided by design patterns like the one defined by Pangaro. Voice AI developers need to start acting like brands, developing personalities and voices that bring the brand to life and are able to interact directly with consumers in a human-like way.

Some companies are already doing this, but it takes a lot of work. For example, PullString created an app for Barbie that lets the doll communicate directly with you. According to Oren Jacob, CEO of PullString, the Hello Barbie companion app has 8,000 lines of dialogue, “… which become tens of thousands of different intents, different context, and ways in which the conversation can branch and change.” Successful as this is, it demonstrates how much time and energy need to be invested to make even the most simple conversations happen between a brand’s voice technology and the consumer.

For marketers, there is a strong benefit to creating real conversations — they drive deeper connections and establish relationships between brand and consumer. Exchanging ideas, sharing goals, and forming agreements help establish a common history and build trust and unity. The more trust we have in the Amazon Skill or Google Home Action we’re installing, the more likely we are to keep using it. The brands that understand the power of a real conversation will be the ones fostering brand loyalty and creating future applications we can’t live without.

Martin Legowiecki is the Technology Director at advertising agency Deutsch and head of the agency’s new AI practice, Great Machine.