Game developers can grow up anywhere these days, and the latest example of that are the Zaeem brothers from Pakistan. Saad, Ammar, and Shayan have created two startups: one that makes mobile games, and a new venture that is creating a platform for multilingual chat in games.

The startups have created jobs in their hometown in Lahore, Pakistan, and Silicon Valley. Their successes are modest by the valley’s standards. But growing up in their part of the world, they overcame a lot of odds and made a rare successful tech and game startup in a fast-moving industry. I met them at a party at the Seattle Aquarium at the game event Casual Connect USA, and their story intrigued me. I met them again at a coffee house in Palo Alto, California, and I listened.

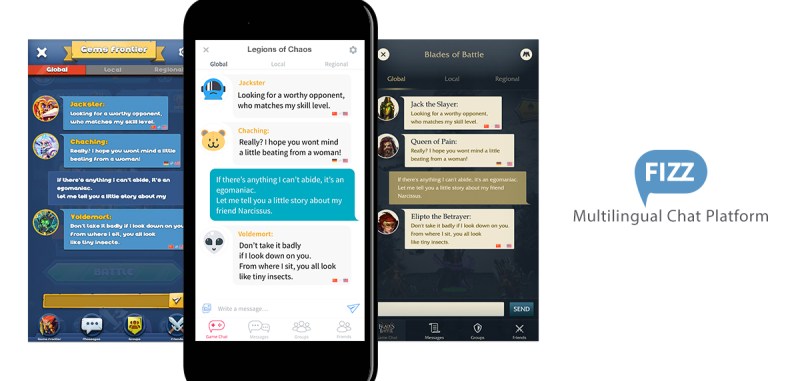

Their Pakistan company, Caramel Tech Studios, has been making mobile games since 2011, and they are creating a new San Francisco startup, Fizz, that promises to do real-time translation for text chat in mobile games. Saad is heading that effort, and he has moved to Silicon Valley to raise money and build the company’s connections to others.

Growing up in Lahore

The brothers credit their entrepreneurial spirit to their father, who’s in textiles and taught them about startups and business. In the late 1990s, when Saad was 14 and Ammar was 12, they learned how to create websites. One company hired them for $700 or so, and that was a lot of money for young Pakistani entrepreneurs. Their parents “acquired” their company and urged them to stay in school.

Above: The Zaeem brothers’ company built Blades of Battle.

“Our father made us watch Pirates of Silicon Valley,” the TV film about Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, said Ammar. “Our dad was our mentor for entrepreneurship from day one.”

The story of the Zaeem brothers is not so different from the twin brothers I met in Israel a couple of years ago. They were at a game conference, and they hailed from Yakutsk, Siberia. They grew up playing video games because it was too cold to go outside. They learned how to make games, and by the time their company, MyTona, shipped their 15th game, they knew how to craft a hit. It got 30 million downloads, and it enabled them to create a studio with 100 employees. Who would have thought you could build such a business in Siberia?

And that story is replaying everywhere where people grow up playing games, study technology, and try to create their own businesses. Part of the inspiration is Silicon Valley’s fairy tale rags-to-riches stories, and part is the desire to play and learn how to build games.

“Back in the ’80s and ’90s, families wanted their children to become medical doctors,” Ammar said. “Now it’s engineering.”

Lucky breaks

Their lives have been full of lucky breaks, made more frequent by their dedication. Ammar was interested in investing in stocks. Saad, the oldest, joined a startup without a salary. He helped the business grow and get work for hire. Then the brothers set up their own company, making software and games for hire. Halfbrick Studios, the Australian game company that made Fruit Ninja, gave the Zaeem brothers their lucky break. It hired them to build a version of Fruit Ninja for the Nokia Symbian phone platform.

“The biggest problem we had was having the cash flow to take bigger risks,” Ammar said.

Above: The Zaeem brothers from Pakistan are making games.

The Halfbrick deal enabled them to boost the company to 22 people in Lahore, which had a good university that produced technical graduates. The Halfbrick job led to more work with Kabam, a mobile game company that made hits such as Kingdoms of Camelot. Andrew Sheppard, then head of studios for Kabam, put Caramel Tech Studios to work on a mobile card strategy game, Order of Elements. The studio then worked for Animoca, a Hong Kong company, to build an Astro Boy mobile game.

Apple liked the idea of a game company in Pakistan, and it featured the title that the brothers made. One of their games, Blades of Battle, has been featured by Apple in 137 countries.

After a while, Caramel Tech Studios started making its own games. That was like moving up the food chain, and it led to more deals. Then Saad stepped down as CEO in 2016 and started the effort to build the chat platform.

Real-time translation

They saw how important chat could be when they added it to one of their existing games. It cost them about $40,000 in development costs, but it enabled the players to be far more social. That snowballed into bigger download numbers and revenues, Ammar said. And once they built chat, they realized they could do it as a platform.

The user interface would be customizable, said Shayan. Customers could slap on their own UIwith their own branding.

Above: Fizz adds real-time translation for multiplayer chat in games.

“We made it into a drag-and-drop” software development kit (SDK), which makes it easy for developers to integrate Fizz. The real-time translation relies on Microsoft’s technology at the moment.

“The real-time translation part is what the companies get excited about, because it is much easier for them to manage one community than a bunch of communities that are separated from each other by language,” Shayan said.

Ammar said, “It’s a win for everybody, and it offloads the developers.”

Saad’s task is to sign up a bunch of customers and raise money. Once that happens, the rest of the Zaeem family’s fairy tale could come true. But Ammar cautioned that simply raising money isn’t success.

“We don’t want to just raise money, inflate it, and be part of the bubble,” Ammar said. “We want to build a real company.”

They also want their success to come back and help Pakistan. They have created some jobs, with 40 people working at Caramel Tech Studios and 20 at Fizz.

But they want to see more tech and game startups there, and venture capitalists as well. Right now, there are few investors, and that makes the tech startups more rare. The investors are present in neighboring India, and Ammar thinks they will show up in Pakistan too. The local stock market has gone up more than 1,000 percent in less than a decade. Pakistan’s historic brain drain could be dampened with home-grown jobs.

“The next five years will be big for Pakistan,” Ammar said.

Disclosure: The organizers of Casual Connect paid my way to Seattle. Our coverage remains objective.