Watch all the Transform 2020 sessions on-demand here.

I met Renee James more than a couple of decades ago, when she was the technical assistant to then Intel CEO Andy Grove, one of the legendary leaders of Silicon Valley. She kept notes on what she learned from Grove, and she rose through the ranks to become president of the world’s biggest chip maker. But she left Intel and the spotlight in February 2016.

And now she’s back, as the CEO of Ampere, a new ARM-based chip company financed by the Carlyle Group. Ampere has hundreds of chip designers making server chips based on the ARM architecture that powers the world’s smartphones. The company promises to give Intel some serious competition in the sweet spot of the server market. The ARM-based chips have 32 cores and will run at speeds above 3 gigahertz on 125 watts of power. It’s a serious effort to provide an alternative form of computing in data centers with different kinds of work loads.

It’s a very ambitious plan, but James said in an interview with VentureBeat that she drew inspiration from her former mentor, Grove, before he passed away in March 2016.

“I remember every word he ever uttered,” she said. “In fact, he and I discussed this before he passed away. He said to me, ‘There’s a lot of easier businesses in the world than this one, but this is worthy.’ I remember everything he taught me, or I wouldn’t be doing this.”

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

James, who after leaving Intel took a job at the investment company Carlyle Group and is now heading Ampere, isn’t going head-on against Intel, which has 99 percent of the server chip market according to market researcher IDC. But she believes the market is ready to embrace alternative processors for certain kinds of workloads. The chips are expected to hit the market in the second half of this year.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: This is the first prototype from ARM-based processor designer Ampere.

Renee James: The company is named Ampere. We’re a new semiconductor company building hyperscale cloud processors to be used in storage as well as servers, based on ARM 64. We’re an ARM licensee, so we’re building our own cores and our own designs. Our first product is in sample now and out in the system. People are working on it. We have a presentation coming, in which you’ll see all of the workloads and software that are already running on it. It’s a 3-Ghz part, 125 watts, so it has excellent total cost of ownership (TCO), excellent price performance.

VentureBeat: I was just visiting some folks at XO, and they said, “You won’t believe it, but we’re seeing a lot of semiconductor startups.”

James: It’s a funny thing. For 10 years there were none. In the last couple of years there have been a bunch of accelerator chips that have gotten different levels of funding. You haven’t seen many CPU companies. When I looked into it and I was talking to VCs and raising money, I realized that there’s a lot of activity and innovation around accelerators for different workloads, but there aren’t a lot of people doing new CPUs. I think everyone in the industry knows that Broadcom sold theirs off. Others have gotten in and out. We’re pretty unique. We’re building microprocessors for servers.

VB: How long ago did you guys get started?

James: I finalized the acquisition about three or four months ago. We’ve been thinking about it and raising money for six to eight months. I acquired a team with a partially finished third-generation design, and I hired the impact engineering team, almost 300 people. I’ve hired a lot of people since then. We’re well on our way. The product is sampling, so it’s out. We’re working on the next design and the design after that, so we’ve brought on a second design team. We have quite a road map planned.

VB: How much of the time since then has gone into this project? Is it just the past year or so, or less?

James: I left on February 1, 2016. It was announced earlier. I worked for the Carlyle Group in private equity. I’ve worked for them for two years. They’re the backers of this, the primary backer, although there are other investors. I started working on this probably inside of 2017. 2016 and the first part of 2017 I was doing other deals and things for Carlyle as an operating executive.

VB: How much has been invested in this? Is it a new investment that you’re leading?

James: It’s a new investment, yes. We’re not talking about the amount. If you travel around the valley and ask people how much money they invest in semis, they’ll tell you anything from nothing to not that much. To do this kind of work, it takes a tremendous amount of investment. We raised quite a bit of money.

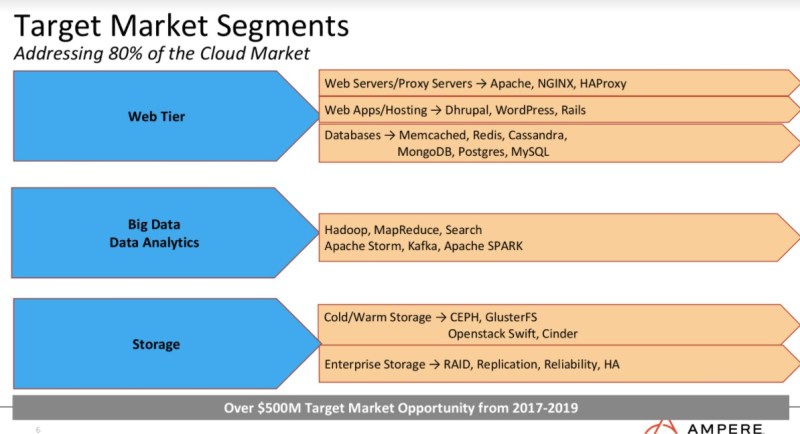

Above: Ampere’s target markets

VB: So it’s more like private equity money than venture capital money.

James: Right. ARM licenses are more than most VCs give in a round. It’s a PE-backed startup.

VB: Where did this team come from?

James: There was an announcement that Carlyle had acquired assets out of Macom. Macom had this team that was working on this, and it wasn’t a business they wanted to go into. It was a team they’d inherited through a different acquisition. We’d been looking at it. When I decided I wanted to start the company I looked at a bunch of different teams that were available, technologies I could purchase to get started. This was one of them. Macom is a semiconductor company out of Boston that has a lot of networking and other assets. They’re public.

VB: Were they already doing a CPU, or were they doing something else?

James: It’s a long history, but the team had been part of a company that did network chips. They had started thinking about doing CPUs, a bit like what Cavium is trying to do, and Marvell, the new merger, from that point of view. Macom bought the entire company, and they said, “We only want to do networking. We don’t want to do CPUs. We don’t understand that business and it’s too much money.” They were looking to sell that off, and we bought that. We were looking at other CPU teams that were available in the Valley, coming from other large companies.

VB: The company that Macom bought, was that Applied Micro?

James: Right. Those guys work for me now. They’ve been on a very long journey, but now they’re out of the dark. In addition to those guys, we’ve hired people from Apple, people from Intel, people from AMD. We have a senior fellow from AMD. We have a really interesting group, a lot of really talented folks. If you knew the Applied Micro guys, you know they’re talented.

Above: Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel.

VB: It’s been a long time since you were helping Andy Grove out there. Did you remember anything he said?

James: I remember every word he ever uttered. In fact, he and I discussed this before he passed away. He said to me, “There’s a lot of easier businesses in the world than this one, but this is worthy.” I remember everything he taught me, or I wouldn’t be doing this.

VB: How did it feel to wrap your head around competing with the likes of Intel?

James: I don’t actually look at it that way. I look at it as investing in what comes next. We’re not building quantum computing. We’re not building high-performance computing. We’re not building legacy enterprise. We’re not building PCs. The list of things I’m not doing that Intel does it long. Intel is the best at what they do and no one knows that better than I do. I would never start a company and raise this much money to go do what Intel does. That’s ridiculous.

I’m doing what I think comes next. I think this is the next platform for the cloud. I’ve had people say, “But it’s too late. It’s already done.” I have to remind them that I worked on the project to make Pentium Pro into an enterprise product when everyone told me that enterprise was done. “It’s done. We use Sun. We use DEC. It’s done.” Not so done, actually? I don’t think we’re over. I think we get to invent the next thing. It’s only over until it isn’t. You know who that sounds like.

VB: Where are you based?

James: Santa Clara, Great America Parkway. We have people in Bangalore, Vietnam, and Portland, Oregon as well.

VB: What is the headcount more like now, beyond that 300?

James: Oh, yes. We’re not 20 people in a garage, even though we’re a startup.

VB: ARM-based servers, can you talk more about that opportunity? It seems like it went up a hype curve and then leveled out, maybe took a dip. Are you feeling like it’s back on track?

James: There was a lot of hope, and it might have been a little premature. Up until this generation of technology, it really wasn’t, I would say, at parity for the enterprise. It wasn’t 64-bit. It didn’t have a lot of the features you need. What’s new now is that the ARM architecture has evolved. The other part is that you have to get it built somewhere. You need a high-performance process and high-performance transistors. Not everyone can build those. We use [contract chip manufacturer] TSMC. It’s a 16-nanometer TSMC part. Our next part will be a 7-nanometer TSMC part.

There’s been a lot of evolution in established semiconductor manufacturing in the last five years. If you look at the hype curve on ARM for the last five to eight years, I agree with you. You’re always thankful to those that came before you, even if some of them died off. They were pioneers. We’re at a point where parity has been achieved, so it’s feasible.

The other thing is, the software ecosystem has completely changed in the last several years. If you were building an ARM part to go into legacy enterprise with a calcified legacy software stack, that’s a tough row to hoe. If you’re building a new part with a new approach to memory and bandwidth and throughput for cloud workloads like in-memory databases and Java and containers and AI, that’s a very different machine. You get to start fresh. It’s fun, right? Every day it’s the beginning again, when we first started building processors for the enterprise.