Sega’s action-adventure series Yakuza first launched in 2005, and Yakuza 6: The Song of Life is the final chapter to protagonist Kiryu Kazuma’s story. His journey has been uniquely Japanese, tackling underground criminal organizations with geopolitical tones, commenting on the way people use technology, and showcasing the country’s culture. Sega’s North American localization team at its subsidiary Atlus acts as the mediator between Western audiences and the streets of Kamurocho, contextualizing Kiryu’s adventures for overseas fans. Yakuza 6 is out in Japan, and will launch in the West on April 17 on PlayStation 4.

“I want to say we’re one of the only publishers making games set in modern-day Japan, a realistic interpretation of that,” said Atlus’s localization producer Scott Strichart in an interview with GamesBeat. “With these games, we’re trying to make sure we straddle this fine line between authenticity and clarity. We want the game to read well. We want the game to play well. We want you to understand it well. But we never want you to forget that you’re a Japanese guy in Japan.”

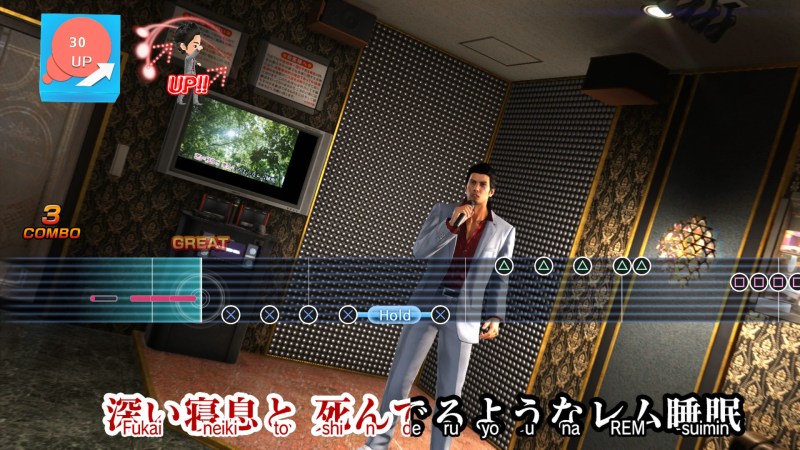

As the name implies, Yakuza is about the exploits of Japanese gangsters. Though the story spotlights warring factions and power struggles between the various mob “families,” it also explores local nightlife. As Kiryu traverses the neon alleyways and clubs of the fictional neighborhoods like Kamurocho, he slips in and out of various people’s lives. Each Yakuza is replete with minigames in which Kiryu races toy cars, sings karaoke, starts a cat cafe, and becomes a minor real estate mogul. Some of these activities may be familiar to Western audiences, while others may require explanation.

In Yakuza 6, the localization team uses the loading screens to share facts. Some are informative, such as explanations about Japanese honorifics, while others are more for flavor, like regional specialty noodles. Strichart says that Sega aims to explain as much as is needed while retaining the original personality, which means not necessarily translating all the words or over-explaining and simplifying concepts.

For instance, instead of replacing the word aniki with English, it’s left as-is. One loading screen explains that aniki is a term of respect and that you might use it to refer to an older brother. But if players don’t totally understand the word, or other concepts, Strichart says that context is there to help convey the gist.

“As much as we’d like to believe we’re giving as much context as possible, that we’re filling out all the holes you might have if you aren’t familiar with Japanese culture, it’s bound to still feel a little foreign,” said Strichart. “That’s totally okay.”

In a few of the games, Kiryu is fresh out of prison and unfamiliar with the explosion of new slang and pop culture trends. Strichart and his team take advantage of these situations, as Kiryu can act as a stand-in for the audience. He doesn’t get all the jokes or all the references, and it’s an opportunity for comedy and explanation.

“If he’s supposed to understand, that puts us into a harder position,” said Strichart. “He’s a Japanese man, obviously. He understands the culture and knows what’s going on. If it’s clear in the Japanese writing that Kiryu’s totally on board, we have to work in a different way—like the word aniki.”

A grown-up sense of humor

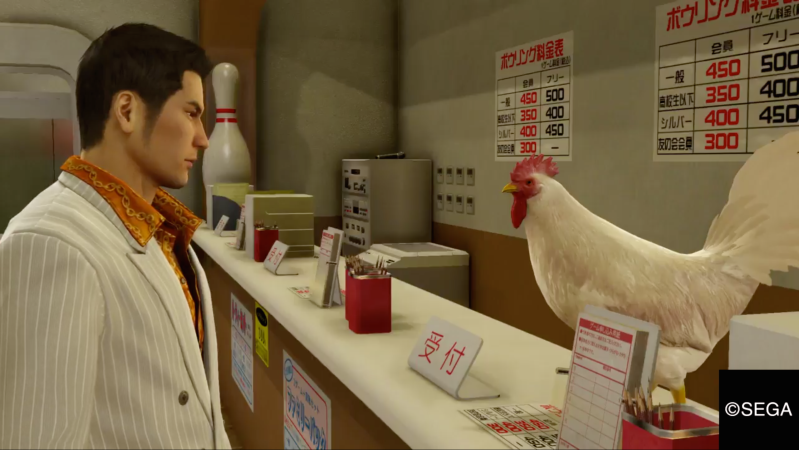

Above: Kiryu meeting his future employee-of-the-month, Nugget.

Though much of the Yakuza games is about brawling with gangsters on the streets, it’s equally about the humor. The snakeskin-wearing Majima Goro is a fan favorite, popping up to challenge Kiryu to fights while wearing increasingly outlandish costumes. And Kiryu himself acts the perfect straight man as strangers on the street pull him to absurd scams and wacky hijinks.

Strichart points to the fact that Yakuza has a mature sense of humor — it’s not so much reliant on slapstick, though that’s in there as well. But it’s a game that targets an adult audience. Some of the subtler humor can be difficult to translate, but overall, Strichart says that the original source material is relatable, which makes their job easier.

“It’s not meant to capture a teenage audience, like so many video games are. It’s built for a working man player who maybe has a kid, who understands that concept at least,” said Strichart. “That’s easy for us to translate, because we get the humor. It makes sense to me. I’m an adult player that they’d be targeting with this game. It’s easy to tell when they’re going for humor. We can say, OK, yeah, this is a funny scene, and we know how that plays out, so we make sure it’s funny in our version too.”

Strichart has had experience writing satire and comedy games. He worked on Izuna 2: Legend of the Unemployed Ninja on the Nintendo DS, as well as the Legend of Zelda parody 3D Dot Game Heroes. He’s now been on the localization team for Yakuza 0, Kiwami, and 6.

“I kind of cut my teeth on funny games for some reason,” said Strichart. “That wasn’t intentional. It was just, ‘This guy writes pretty good humor, so let’s assign him the funny games.’ I guess that worked out for me.”

Much of Yakuza’s humor is in the way Kiryu interacts with the folks he encounters. He’s out of touch and doesn’t understand what the fuss is about when it comes to social media. Sometimes he’s endearingly goofy, and confident enough to not care what people think. When he bowls a turkey (three strikes in a row) in Yakuza 0, the bowling alley attendant gives him a live chicken — which he keeps, names Nugget, and hires as a manager for his budding real estate empire.

“Sometimes playing these utterly ridiculous scenarios in a totally normal way is what makes it funny,” said Strichart. “Sometimes it’s just word choice. If it’s a word that triggers something funny here, we can use something, if it makes sense in context, to elicit the same response.”

Localizing geography

As in the U.S., Japanese sports a wide variety of accents. Strichart says that every localization team has its own approach. His philosophy is to capture more of the feel rather than simply changing up the way it’s presented in English to indicate that one character speaks differently from another.

“There’s no 1-to-1 comparison. So looking at this kind of Osaka stereotype — a person who’s fast-talking, super casual, uses a lot of metaphor, a lot of hyperbole — those are the things that now shape our Kansai dialect,” said Strichart. “You see that in the way we drop the ‘Gs’ off things. We’re trying to indicate a really fast style of talking. It’s tough to write in that style sometimes. It’s tough to tell my team, this is how I do it and now you need to replicate it. It was a stylistic choice that I made, to do that, and at the end of the day I think it’s paid off.”

The team doesn’t simply find analogous North American accents. Instead, it charts the qualities associated with someone from that particular region in Japan. Strichart points to Hiroshima as an example, noting that it’s a “slow, sleepy town.”

“The people there are perceived as being kind of disconnected from the fast-paced, modern world of Tokyo,” said Strichart. “We did give it a slower, more words-in-the-text kind of approach. They connect words in ways the other characters won’t. It’s a refining process to go through.”

Other characters have a more direct kind of translation. For instance, Chinese gangsters who are speaking broken Japanese also speak broken English.

Some geography-related translation is complex and left mainly without subtext because it would be too complicated to explain. For instance, the team doesn’t go out of its way to delve the complexities of geopolitics in Asia. China and Japan have a fractious history, and knowledge of that could help explain some of the turf war between the Chinese and Japanese gangsters. On that front, Strichart’s team leans on the plot to get across the essentials.

“The plot has clearly explained that this is a Chinese mafia against a Japanese mafia,” said Strichart. “While you may not understand the entirety of that tumultuous history, you at least understand that there’s a conflict. I don’t know that it’s our role as localizers to be like, this is the conflict that Japan and China are going through over these years of history. You don’t need that much context to understand that these two mafias are fighting.”

Localization process

Strichart gives a lot of credit to the Japanese writers for Yakuza’s story. That’s pressure on the localization team as well, since they’re working to present the content as authentically as possible.

“I have a team of people who help me with this game, because I can’t possibly localize the entire content of this myself,” said Strichart. “Having to review their work, making sure it’s consistent with all this other stuff, keeping up a literal Wikipedia of this game in my head, just making sure the text is servicing the Japanese well-written content—we want to make sure this reads and plays like a movie-quality kind of game. Sometimes that’s asking a lot. You have to be a good writer to be in this kind of field. I demand that of my team.”

The localization team tries to get its hands on the game as soon as possible, though when it’s actually able to get to work depends on the developers. Once it has the Japanese version, it starts a dialogue with the developers about what needs to change as well as getting a handle on what can’t be altered.

“We start looking at things and flagging stuff: oh, that needs to change, that’s not going to work, this is the wrong order,” said Strichart. “We write spec change requests. ‘This isn’t going to work for the U.S., can we do it this way?’ Maybe that won’t work, because the code won’t allow it. We have an open dialogue, which definitely works.”

Internally, the team also flags sensitive topics. In Yakuza Kiwami, for instance, the hostess Rina comes out to Kiryu as a lesbian. Strichart says that the writers spent extra time on that segment to make sure it was treated thoughtfully. This is likely because these segments of the game will be scrutinized by players in the West. Games have a spotty record with representation, and Atlus itself has been criticized for the way it portrays queer or trans characters in games like Persona 5 and the upcoming Catherine: Full Body.

The localization team has no control over the source material, but it’s focused on accurately representing what the original writers intended.

“We had to play that very carefully, put extra finesse into that text and really understand that character and what Japan was saying and how it needed to be said in our text,” said Strichart. “As a result, that’s one of the most screenshotted parts of Yakuza Kiwami, the reaction that Kiryu has to her almost giving up and being like, ‘I should just go and look for guys.’ No, you shouldn’t give up on that, because this is who you are and what you’re about. That comes from what the Japanese was saying, and we took that into English in a way that hopefully made sense to everyone.”

Localization is crucial for games like Yakuza, which are intrinsically tied to the culture in which it’s made. The teams operate mainly behind-the-scenes, but Strichart and senior localization producer Sam Mullen have been livestreaming question-and-answer sessions to go a little more in depth about the process, unraveling some of the trickier topics such as the relationship between China and Japan or explaining the unique ambient noise in Japan. Localization tackles a lot of nuance that players may take for granted — and it also leaves some details ambiguous or up to interpretation. Ultimately, Strichart says that the players are here for the game as a whole.

“One of the things I like to tell young localizers is you can write the best game, spend as much time as you want to, finesse every word, and if the game is not good you cannot save it,” said Strichart. “Nothing you can do is make the game better. At the end of the day it’s a game and it has to play better. That’s what’s going to sell it. But a bad localization can sink it. A bad localization can become a source of controversy. People talk about the game for the wrong reasons. If you’re not paying attention to that, you’re sinking the game. That’s not good.

I don’t want to underplay the importance of a good localization, because it’s important. It’s absolutely valid. But when someone says, that game has such good writing, that’s not us they’re talking about. They’re talking about Japan. They’re talking about this game’s script. We facilitate their being able to say that. That’s kind of my attitude toward it. You need us to put the words into English, but at the same time, we should be a kind of invisible process. It’s not about us.”

Even if Strichart says it’s not about them, fans seem to still be interested. His and Mullen’s livestreamed Q&A sessions have been getting steady viewership, averaging around 10,000 to 12,000 views when the videos are posted on Sega’s Facebook page. With its translation of Yakuza’s jokes, the localization team has landed the punchlines — and a loyal following.