International Women’s Day was one of the most celebrated women’s events in history. It was observed with a sense of urgency, as it came in the wake of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. It made me think again about the video game business and its own struggle to recognize its pioneering leader Nolan Bushnell, cofounder of Atari.

I’ve had a few weeks to think about this now, and it reminded me that with time comes perspective. For the women’s day event, we saw companies such as Google, Zynga, Facebook, and others come out to express their support for women in games, where only one in five employees is female despite the fact that nearly half of all gamers are women. This is our context for viewing Bushnell today.

Bushnell made headlines a month ago when the Game Developers Conference first decided to award him its Pioneer award for starting Atari with Ted Dabney in 1972. Then, on January 31, a day later, it rescinded the award after protests by the #NotNolan Twitter campaign started by activist and Congressional candidate Brianna Wu. The GDC was concerned about Bushnell’s past comments about women and the sex-filled environment he created at Atari in the freewheeling 1970s.

GDC is coming up in just over a week, and the dust has settled some. I’ve had some time to interview a few women who worked at Atari and loved the environment that Bushnell created. Kotaku spoke to a bunch of these women, who surfaced on the Atari Museum forum, on Facebook as well. What emerged was a strange narrative, where older women were criticizing younger women for saying that the work environment of the old days was sexist. These older women had decades of time and perspective.

“I know there are people out there who are accused and really were guilty of sexual harassment,” said Carol Kantor, a former Atari employee from the early days until 1979. “But not Nolan. It wasn’t in his character. I certainly stand up for the Nolan that I knew. He certainly didn’t hold his power over people.”

Above: Carol Kantor, former Atari market researcher, worked at the company from 1973 to 1999.

Bushnell reacted to the rescinding of the award by applauding the GDC and then apologizing to those he might have offended over the years. Many assumed he was hiding something that might come out later. It was as if he expected some further accusation of sexual harassment or assault to surface, and he was heading it off, the rumors suggested.

“I applaud the GDC for ensuring that their institution reflects what is right, specifically with regards to how people should be treated in the workplace,” Bushnell said at the time the award was rescinded. “And if that means an award is the price I have to pay personally so the whole industry may be more aware and sensitive to these issues, I applaud that, too. If my personal actions of anyone who ever worked with me offended or caused pain to anyone at our companies, then I apologize without reservation.”

That last part seemed a little equivocal, but you have to figure that someone might have surfaced, considering Bushnell was a boss in the game business for the better part of four decades. He covered himself with that comment. But the Atari women and others have noted that no one came forward to complain about Bushnell. Compare that to the aftermath of the first complaints about disgraced movie mogul Harvey Weinstein or convicted gymnast abuser Larry Nassar.

I could still be wrong, but based on the lack of new complaints, I’m going to conclude that Bushnell was different from them. Steven L. Kent, an early game journalist and now a science fiction writer, told me he never heard anything negative about Bushnell in terms of sexual harassment.

Over the years, Bushnell has not behaved like a man who has secrets. He has openly talked about Atari’s wild culture, mostly in a context of how it was a special place. It had hot tub parties where executives held meetings with women in bikinis, and it did other things that you wouldn’t do today.

Kotaku quite casually reported that a porno film was shot at Atari’s headquarters, but that didn’t lead to a big freak out about Bushnell. It didn’t cause a chorus of voices to say that the GDC did the right thing. The hot tub antics of Bushnell in the pot-fogged 1970s might be viewed as highly inappropriate from today’s perspective, but the elders say that’s the wrong way to look at history. To draw the right lessons from the past, you have to understand the context of what was happening then.

Above: Loni Reeder, former Atari employee.

Loni Reeder, a woman who worked at Atari from 1977 to 1979, said that Atari was the best place she ever worked — and that she helped design the hot tub that was built in one of the engineering buildings. She got her receptionist job because she was persistent, and Bushnell concluded, “Let’s give her the job because she wants it the most.” She worked her way up to communications and security.

“I take great offense of people coming in today and saying we were oppressed,” Reeder said. “I’m a strong woman. No one will push me around. I was sad to see what happened to Nolan. We had a united and cohesive environment. That was what the ’70s were about. It wasn’t like we all got together to have an orgy.”

She noted that the hot tub was co-ed only one day a week.

“We had a cutting-edge company. Nolan was a larger-than-life personality,” Reeder said. “He had no problems going to his house and posing for a picture in a hot tub. He wasn’t pushing sexual advances on anybody.”

Above: Elaine Shirley, former Atari worker.

I talked to other former original Atari women like Kantor and Elaine Shirley, and they said they never saw Bushnell do anything that added up to harassment. It was a consensual workplace, they said.

“I call bullshit on those people who said that we were harassed,” said Shirley, who worked at Atari from 1973 to 1999. “I’m not against the movement. But how can the speak for us? The people who grew up there and worked there. I loved it. I started at $2.29 per hour, and I made six figures by the time I left. We were strong women. It wasn’t that we were weak. I never saw a hostile work environment, and I had 10 different jobs there.”

She added, “It was the best work environment ever. I find it very unfair for them to attack someone or something they don’t know about.”

But I also realized that no amount of interviewing such talkative people was ever going to satisfy doubters, since you can’t prove a negative. Reeder attacked Wu for her stance, saying she wasn’t there, so she couldn’t know what happened at Atari. Wu’s view was that she didn’t have to be there because of what was said so publicly. With the advantage of hindsight and today’s standards, Wu concludes that Bushnell’s sexist comments and Atari’s sexual environment had to be hostile.

“Some of us are #MeToo survivors too,” Reeder said. “Some have had sexual assaults in our lives. We know the difference. There is nothing to say here. We had an HR department. If issues came up, we would know. They didn’t come up.”

That’s a hard concept to grasp. Does the absence of a smoking gun prove someone’s innocence? We need to listen when women complain. We need to believe them enough to investigate the truth. We need to understand both sides of the story. And when we investigate and find nothing, as in the case of Bushnell, we should say so.

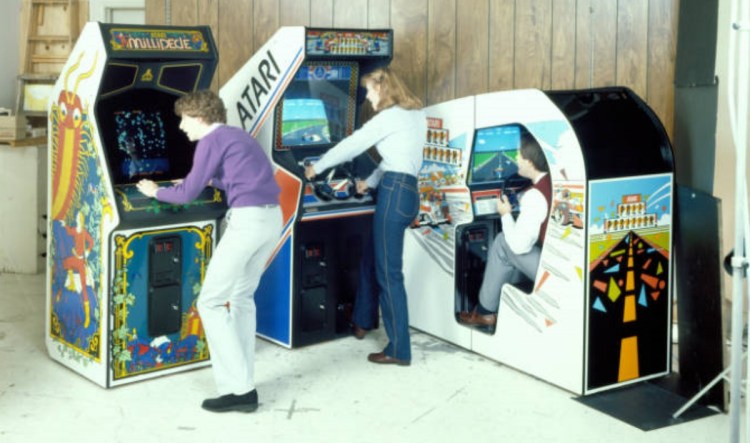

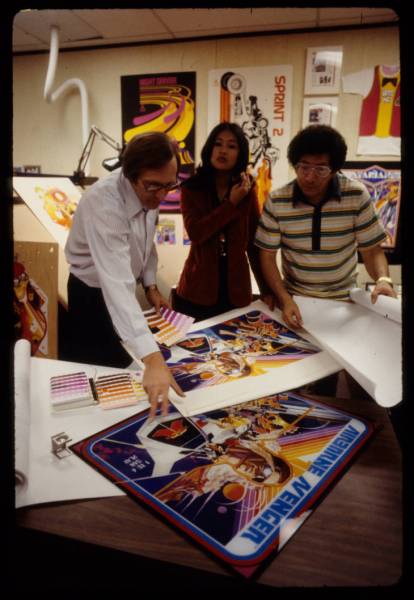

Above: Atari in its heyday.

It’s worth pointing out Atari had a lot of women, and it had women in management roles. It was a place that had one of the first female game designers, Carol Shaw, who went on to design River Raid at Activision.

I think it’s important to listen to the stories of these women, and for the museums of today (like The Strong National Museum of Play, which provided some of the photos here) to record their perspectives while they are still so talkative and accessible. I do not dismiss what they say out of hand because they choose to see Atari the way it was, rather than the way that it looks to people who were born many years later. I do not think, on the other hand, that the media deliberately suppressed the stories of the Atari women because they didn’t fit neatly with today’s #MeToo narrative. And I think their history, or herstory, is interesting whether or not you are trying to find out more about Bushnell.

Atari has a 50th reunion coming up, and women like Reeder are looking forward to it.

“Many of us saw Atari as one of the best working experiences of our lives,” Reeder said. “After we left, we were chasing that experience. I went to NASA afterward, and that was a big switch.”

I’m fully prepared to think about Bushnell for a while. I think that a decade from now, we should look back on this moment. I could be wrong. We could all be wrong. The facts sometimes take their own time to take shape, and the proper perspective may come into view. I sure hope it does.

But for now, I sure feel good that Nolan Bushnell was the father of commercial video games, and he created an environment that was so memorable to people who support him so many decades later. Even in an age of herstory, he just might win that Pioneer award still.