Like flying cars and robot assistants, holograms have spent almost my entire life being “only a few years away” from ubiquity. The hologram rush began when National Geographic featured 3D skulls, eagles, and globes on the covers of its magazines. Naturally, as the sci-fi concept had finally become somewhat tangible, people began to assume that holographic TVs would soon bring realistic 3D images into their living rooms.

That didn’t happen, and it didn’t really come close. In 1992, Sega released a single holographic arcade game, Holosseum, that turned out to be a smoke-and-mirror trick minus the smoke. The in-game imagery was flat, but it appeared to be floating on a black stage, and the gameplay was just as two-dimensional. By the turn of the century, holograms were nowhere to be found save as counterfeiting protections on currency and certain products. Holographic homes and boardrooms have remained the stuff of science fiction.

But people still dream about bringing holograms into their lives. From Minority Report‘s barely holographic transparent touchscreens to Blade Runner 2049‘s vividly 3D moving hologram projectors, movies forecast that we’ll all be interacting naturally with ghostly holograms. Games, too: Helpful holograms pop up in the hallways of Doom VFR, and Microsoft’s Halo introduced Cortana as a volumetric projection from screens and gloves.

Above: Microsoft’s Cortana evolved from a Halo hologram into an AI assistant

Meanwhile, in the real world, RED apparently now plans to sell a holographic phone this summer for $1,300 and up. And if 5G cellular chipmakers and phone carriers can be believed, actual holograms of some sort will indeed start showing up in homes and conference rooms this decade, powered by next-generation wireless networks.

These near-term future technologies have been preceded by a new form of fauxlogram based on a different display technology — specifically, a shift from projectors to tiny screens mounted right in front of participants’ eyes. AR and VR glasses display the hologram either mixed in with real-world surroundings (AR) or placed within a fully artificial space (VR).

https://youtu.be/jl8ziNFJBa4

Microsoft foreshadowed this development with the announcement of HoloLens more than three years ago, but even two years after its $3,000 AR headset went on sale for developers, it remains a technological curiosity. Although its demos of holographic Minecraft levels are cool, there’s still not a real consumer product there — something Microsoft appeared to understand in 2015, when it described HoloLens as being on a “five-year journey” to consumers.

Some people don’t want to wait until 2020. Over the last week, Leap Motion debuted North Star, a superior alternative it claims can be made for under $100 at scale. Its headset looks sort of like a Jetsons interpretation of a futuristic samurai helmet, but packs twin high-res screens and advanced hand tracking capabilities. Like HoloLens, the “real consumer product?” question applies here, but Leap is determined to start a conversation about making virtual interfaces real.

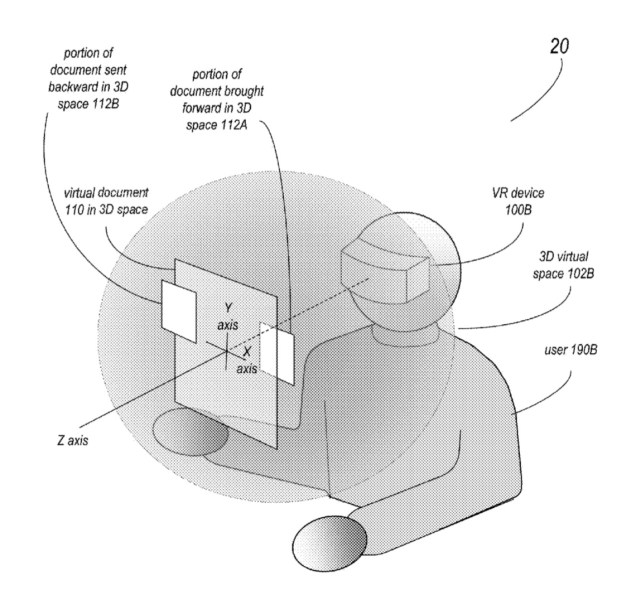

Above: Apple patent application for VR computer interface.

I have to admit that the idea of having “holograms” appear through AR and VR trickery rather than live projection doesn’t bother me; thanks to a steady diet of sci-fi movies like the Iron Man series, I’m excited for the day when I can use gadgets and tools that disappear. If that’s accomplished through a pair of glasses, I’m OK with that so long as the overall experience is much better than what I’d get without glasses.

Like Microsoft, Apple’s been working on virtual interfaces for years. After initially conceiving of a virtual computer projected on a wall, Apple recently applied to patent using VR glasses to display a traditional computer interface — including word processing. Forget about carrying a laptop; instead, you’ll just keep a Bluetooth keyboard in your bag and look at a virtual computer screen through glasses.

Until a full-fledged solution is available, I’ll content myself to watch Leap Motion’s demo videos and imagine how the virtual tools of tomorrow will work. They’re only a few years away at this point … right?