Last April, I started a conversation with cybersecurity company Bromium. The company was keen to uncover where the streams of revenue generated by cybercrime eventually go and whether this money is ultimately supporting other areas of crime. Over the past 10 months, I have been examining this question, and I must say there have been some eyebrow-raising findings.

While there has been a lot of research into areas such as the “cost” and the mechanisms of cybercrime, there is far less awareness and understanding of how cybercrime functions as an integrated set of criminal practices. As a result, the tech community tends to focus on technical factors, such as malware types, security holes, and how to prevent certain types of attacks. My goal was to get a better sense of how the cybercrime economy works.

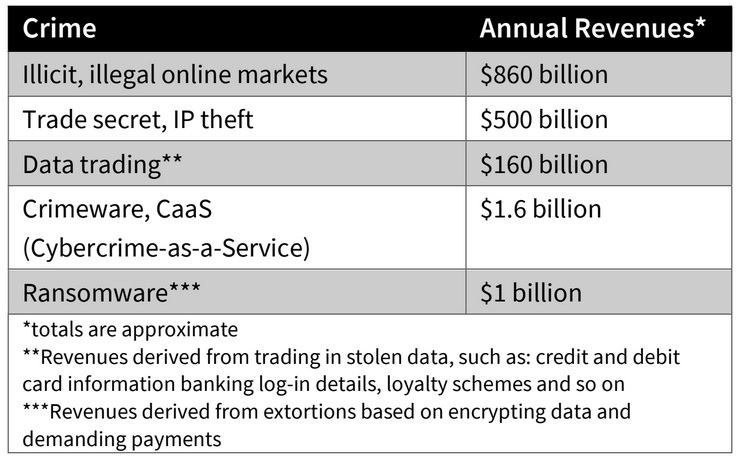

Cybercrime revenues reach $1.5 trillion

Though it constitutes a relatively new criminal economy, cybercrime is already generating at least $1.5 trillion in revenues every year, according to my research. This is a conservative estimate, based only data drawn from pnly five of the highest profile, most lucrative varieties of revenue-generating cybercrimes:

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Looking at cybercrime revenues gives us a new way of understanding these offenses compared to measuring cybercrime in terms of the losses it causes. The earnings of individual cybercriminals within such categories exceed their counterparts in the traditional crime world. And while total revenue from traditional crime is probably still higher overall, it is by no means clear how long this will continue – especially given the increasing interdependence between cyber and traditional methods, as for example, in counterfeiting.

There is evidence that cybercriminals’ revenues often exceed those of legitimate companies – especially at the small-mid range size. In fact, revenue generation in the cybercrime economy takes place at a variety of levels, from large “multinational” operations that can generate profits of over $1 billion to small scale operations, where profits of $30,000- $50,000 are more the norm.

And individual earnings from cybercrime are now on average,10-15 percent higher than most traditional crimes.

High-earning cybercriminals can make $166,000+ pe rmonth. Middle-earners can make $75,000+ per month.

And low-earners can make $3,500+ per month.

Disposal of cybercrime Funds

Now to answer Bromium’s question: Are cybercriminal revenues supporting further cybercrime? Looking at interview and observational data of a sample of individuals either convicted or currently engaged in cybercriminal activities, I found that:

- 15 percent of cybercriminals spent the majority of their revenues on covering immediate needs – such as buying diapers or paying bills.

- 20 percent focused on disorganized or hedonistic spending – for instance, buying drugs or paying prostitutes.

- 15 percent directed their revenues towards more calculated spending to attain status, or to impress partners and other criminals – for example, buying expensive jewelry.

- 30 percent converted some of their revenues into assets – such as property.

- 20 percent used at least some of their revenues to reinvest in further criminal activities – for example, buying equipment or more crimeware, as well as channeling revenues to the production of illegal drugs, human trafficking, and terrorism.

These results indicate structural continuities in the way revenues are used by criminals, suggesting the rewards sought by cybercriminals have not changed very much from their traditional counterparts. Significantly, we see some revenues being invested in further cybercrime. This may be in the form of relatively low-level purchases on equipment and tools, or higher-end long-term investments in further crime.

More concerning is evidence that cybercrime revenues are now significant enough to attract the attention of those who are ready to use them to fund more serious crime, such as human trafficking, drug production or even terrorism.

At least 30 percent of the sample of cybercriminals questioned as part of my research said they had physically transferred cyber revenues or sent money via couriers on airlines to deposit in foreign banks. A couple more data points my research undercovered:

- Digital payment systems were used as laundering tools in at least 20 percent of the cases I sampled – with PayPal playing a part in at least 10 percent of cases.

- 95 percent of ransomware profits were cashed or laundered with the cryptocurrency trading platform BTC-e, which ceased trading in July of last year after interventions from international law enforcement but later reopened.

The emergence of platform criminality

The metaphor of “cybercrime as a business” is no longer adequate to capture its complexities. A more appropriate metaphor is an economy; a structure functioning as a literal “Web of Profit” – a hyper-connected range of economic agents, economic relationships, and other factors now capable of generating, supporting, and maintaining criminal revenues at unprecedented scale.

This Web of Profit does not just feed off its legitimate counterpart, it also supports and bolsters revenue generation and profit in the conventional world. The result is a growing interconnectedness and interdependence between them. Companies and nation states are now involved, using cybercrime to acquire data and competitive advantages and as a strategic tool in a quest for global advancement and social control.

The cybercrime economy has also become a kind of mirror image of contemporary capitalism – reproducing disruptive business models popularized by the likes of Amazon and Uber. As a kind of “monstrous double” of the legitimate information economy – where data is king – The Web of Profit is not just feeding off the wealth it generates, it is reproducing and, in some cases, outperforming the legitimate information economy. Cybercriminals are mirroring legitimate businesses organizations and emulating “platform capitalism.”

There are large organizations in the burgeoning cybercrime economy that very closely match the structures and business plans of companies like Uber, AirBnB, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. These platform owners act more like service providers than criminals; they don’t commit the crimes directly but enable and profit from cybercrime and are helping to create a world where cybercrime is a permanent state.

Such sites offer more than tools; they include customer reviews, technical support, descriptions, ratings and

information on success rates. Some examples of the services on offer:

- A zero-day Adobe exploit can cost $30,000.

- A zero-day iOS exploit can cost up to $250,000.

- Malware exploit kits cost $200-$600 per exploit.

- Blackhole exploit kits cost $700 for a month’s leasing, or $1,500 for a year.

- Custom spyware costs $200.

- One month of SMS spoofing costs $20.

- A hacker-for-hire costs around $200 for a small hack.

Fighting the market

Understanding revenue generation and how it flows can help the tech community develop new options to disrupt cybercrime and can help law enforcement fight the problem. But another key takeaway is that there needs to be greater collaboration to address this issue. To effectively combat cybercrime, we need a holistic approach. Focusing on specific types of cybercrime and the way they are committed is only effective to a point. Without a holistic overview, one that considers the dynamic and interconnected nature of the cybercrime economy, we will never have a full and accurate understanding of the problem.

Organizations and the cyber security industry need to move beyond simplistic firefighting and focus more clearly on responding to the cybercrime economy.

[This post is based on an excerpt of a report released April 20, written by the author and commissioned by Bromium, entitled “Into the Web of Profit.”]

Mike McGuire is Senior Lecturer in Criminology at the University of Surrey.