Provizio raises $6.2 million to develop AI that reduces automotive fatalities

Analysis

MediaTek wants to help education-focused tablet makers beat the iPad

Dtex raises $17.5 million to detect cyberthreats with AI while preserving privacy

BlackCloak: Credentials for 68% of top pharma executives are available on the dark web

Open RAN Policy Coalition unites 31 tech companies to lobby U.S. on 5G

Firefox 76 arrives with password management and Zoom improvements

IBM’s Watson AIOps automates IT anomaly detection and remediation

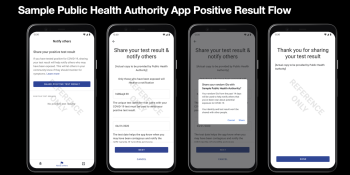

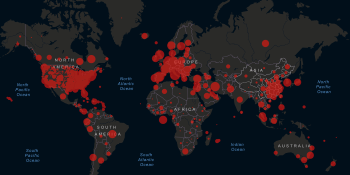

Apple and Google prohibit location tracking in new contact tracing guidelines

India orders coronavirus tracing app for all public and private sector employees

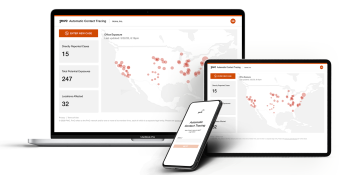

PwC’s workplace contact tracing app won’t share info with public health officials

Facebook now lets U.S. users transfer images and videos directly to Google Photos

Apple releases iOS 13.5 beta with coronavirus exposure notification (Updated: Google too)

Rapid7 acquires cloud infrastructure automation platform DivvyCloud for $145 million

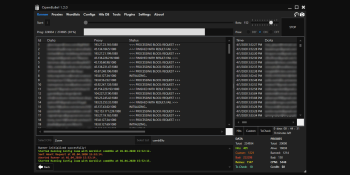

Market for stolen Zoom credentials is booming

Secret Double Octopus raises $15 million to authenticate employees without passwords

Companies equip cameras with AI to track social distancing and mask-wearing

Australia launches controversial coronavirus contact tracing app

Facebook removes pseudoscience ad targeting category

Google launches Android 11 Developer Preview 3 with app exit reasons, ADB Incremental, and wireless debugging

Randori raises $20 million to spot cyberattacks with AI

Researchers find actively exploited iOS flaws that were open for years

ForgeRock raises $93.5 million to automate identity and access management

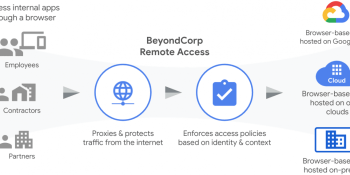

Google rolls out BeyondCorp for secure remote network access without a VPN

Amazon deploys thermal cameras at U.S. warehouses to scan for fevers faster

U.S. judge blocks Twitter’s bid to reveal government surveillance requests

Opinion

ProBeat: Apple and Google’s contact detection API will fail, but they should build it anyway

AI researchers propose ‘bias bounties’ to put ethics principles into practice

Apple and Google weigh privacy concerns as EU demands coronavirus apps not track location data

Google Meet gets Gmail integration, will soon display up to 16 video call participants

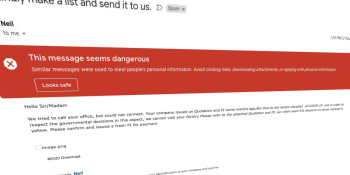

Gmail is blocking 18 million malicious coronavirus emails a day

Facebook to alert users exposed to coronavirus misinformation

Health care organizations use Nvidia’s Clara federated learning to improve mammogram analysis AI

Awake Security raises $36 million for AI that identifies network threats

AI behavioral biometric startup BioCatch raises $145 million

Unit 42: Phishing attacks are thriving during the pandemic

AI Weekly: The sudden speed of technological change in a coronavirus world

Opinion