testsetset

The four years that William Morgan spent as an engineer at Twitter battling the Fail Whale gave him a painful view into what happens when a company’s rickety web infrastructure gets spread too thin. But while Twitter’s instability was highly publicized, Morgan realized that the phenomenon existed to some degree across the web, as companies were building applications in ways that were never intended to handle such scale.

The result: Applications and software were becoming too expensive, too hard to manage, and too slow to deploy, they required too many developers and caused too much downtime.

After leaving Twitter in 2014, Morgan wanted to use some of the lessons he had learned to help other companies reimagine the way they build applications for the web. That led to the founding in 2015 of Buoyant, whose application development tools have become part of an insurgent movement to fundamentally transform the way software and services are designed for the web.

Referring to what is in some cases dubbed “microservices” or “cloud native computing,” the development philosophy holds that breaking applications into smaller, self-contained units can significantly reduce costs and time needed to write, deploy, and manage each one. The result should be a web that is faster yet more stable. And just as compelling to proponents, it should deliver a more open web that makes it easier for users to change cloud platforms.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

While such shifts in development philosophy typically take many years, cloud native computing has caught fire and is having a big moment. Even though it remains small overall, the uptake and enthusiasm has even taken advocates like Morgan by surprise.

“It’s kind of incredible how rapidly this has been growing,” he said. “It speaks to the fact that people are focused on the right thing, which is solving actual problems. What we are seeing here is just a beginning. But I think this could fundamentally change everything about web development.”

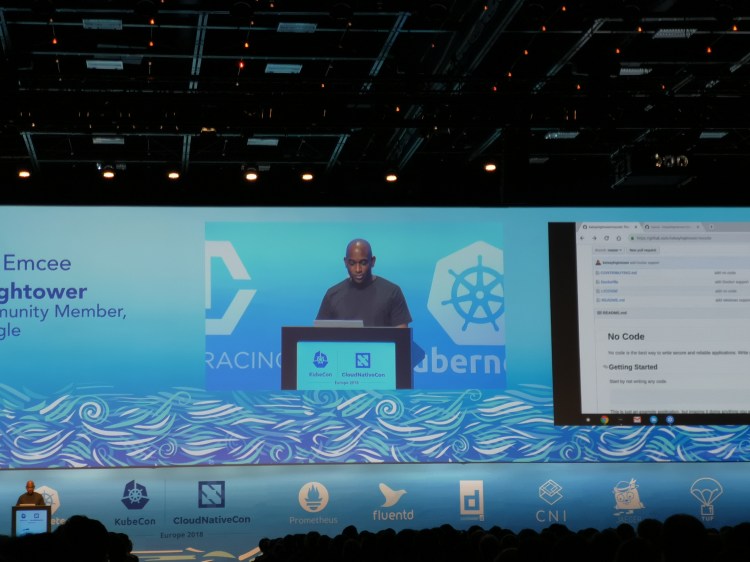

That optimism was on display this week at the latest edition of a conference called KubeCon + CloudNativeCon Europe 2018 in Copenhagen, Denmark. The event drew Morgan, along with 4,300 other attendees from around the world. While conferences are never a perfect barometer of an industry, that figure is up from the 500 people who attended the first such gathering in November 2015.

The event is organized by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, an open source organization that operates under the umbrella of the Linux Foundation. CNCF was created just over three years ago to shepherd this new movement.

The current momentum around cloud native computing seems to be a function of both the right solution and the right timing.

As web development has evolved, there has been a tendency to develop “monolithic” applications — that is, software that contains most or all parts of the code for a given company or service. Over time, those code bases have grown to massive sizes and become hugely complex, which has led to a wide array of problems.

Developing and maintaining such applications can take an enormous number of developers. Even for companies that have made the necessary investments and hired those developers, making any changes or updates can be cumbersome and take weeks. For others, the resources needed to build the technology can seem like an insurmountable challenge.

“Software has gotten a lot more complex,” said Ben Sigelman, cofounder and CEO of LightStep, a San Francisco-based startup that makes performance management tools for microservices. “It’s gotten a lot more powerful, but it crossed a threshold where the complexity of the code to deliver those features requires hundreds and hundreds of developers. And once you have hundreds of developers working on the code, you’re in a dangerous place. It’s an efficiency issue, and it can lead to paralysis.”

The solution, according to adherents of cloud native computing, is to break these big slabs of code into self-contained functions or features. This modular approach, particularly if it’s based on open sources tools, would ideally make constructing web services and maintaining them far more efficient. Each piece could be deployed or updated rapidly, by fewer developers, without having to worry that it’s going to blow up the entire code base.

This concept of microservices has been floating around for some time. But it got a big boost in 2013 when San Francisco-based Docker released its first product. Docker helped popularize the use of “containers,” a technology that places all the necessary pieces for an application to run in one package. That allows the application to be moved across different platforms and operating systems without having to be rewritten.

The following year, Google announced a project some of its engineers had been developing to enable the deployment and management of containerized applications called Kubernetes. While Google felt that Kubernetes could provide a powerful boost to cloud-based services, it also recognized that its acceptance would be limited as long as it was seen as a Google project, according to Kelsey Hightower, Google’s Kubernetes community member and co-chair of the KubeCon conference.

So Google approached the Linux Foundation about open-sourcing Kubernetes. Those talks led to the creation of CNCF, which also counted Twitter, Huawei, Intel, Cisco, IBM, Docker, Univa, and VMware among its founding members. Rather than being just a Kubernetes project, the foundation decided to take a wider view, positioning itself as a body that would oversee and encourage development of all the pieces needed to build applications using this new model. CNCF says it now has 20 projects — including Kubernetes — in some stage of development.

Just as critically, CNCF now counts every major cloud service provider as a member. Over the past 12 months, Dan Kohn, executive director of CNCF, said he has been surprised by how quickly industry partners, many of them cloud platform rivals, have bought into the movement and joined the foundation. Microsoft announced it was joining last July. Amazon Web Services joined last August and hosted a networking event for developers at KubeCon. While Docker was already a founding member, it announced it was going to become more deeply involved by donating another of its tools, Containerd, to CNCF last year and doing more to support Kubernetes.

“The aspiration was always to get everyone around the table,” said Kohn. “Frankly, I didn’t expect it to happen so quickly.”

It wasn’t necessarily an easy decision for the companies. The fight to win in the public cloud space is a fierce one. Tools like Kubernetes and microservices eliminate some competitive advantages because they allow for easier data portability. For companies just moving into the cloud-based world, the ability to avoid the risk of vendor lock-in is another appeal of cloud native computing.

“Everyone is so conscious of software coming from one source,” said Gareth Rushgrove, a Docker product manager. “They are worried they might not be able to get out from under one vendor solution. That’s one of the reasons CNCF and this community have been so useful.”

So what was the catalyst? Most likely these companies saw the reality of where the market was heading as use of Kubernetes continued growing quickly. More companies are under pressure to digitize, and they increasingly see cloud native computing as a faster and easier way to get there.

“The users are what is really driving this,” said Abby Kearn, executive director of open source organization Cloud Foundry, a CNCF sister group under the Linux Foundation umbrella. “They need to digitally transform and become technology companies. If you’re a bank, and you’re not transforming and trying to become a technology company, where does that leave you? You’ve got a ton of fintech companies coming for your customers.”

At the three-day conference, organizers announced that Chinese internet giant JD.com had 20,000 servers running Kubernetes, making it one of the largest adopters in the world. A report commissioned by LightStep, which surveyed 353 developers from companies around the world, found that 86 percent expect microservices will become the default development architecture within five years. And the three-day KubeCon was packed with participating companies making announcements designed to expand the ecosystem of related products and services.

Jason McGee, vice president and CTO of IBM Cloud Platform, said his company is betting big on cloud native solutions because they have the potential to help its customers move faster. Microservices are allowing companies to mix and match containerized, open source solutions so they don’t have to build everything from scratch.

“I can build a microservice that you can re-use,” McGee said. “That will allow the overall industry to go faster. Right now, we spend a lot of time re-solving the same problems.”

Naturally, this frenzy has sparked interest from venture capitalists. Buoyant has raised $14 million. And LightStep has raised $27 million over two rounds after Sigelman initially told potential Series A investors to hold off because he wasn’t sure how quickly users might embrace microservices.

“I knew that the idea made sense,” said Sigelman, who worked at Google for nine years before striking out on his own. “I didn’t know about the timing. I told Series A investors to wait for it. I knew it was going to happen. I didn’t know when.”

For all this optimism, there are still plenty of skeptics who see cloud native computing and microservices as an overhyped development fad. Even CNCF members openly acknowledge that many challenges lie ahead. Speaking on stage to open the conference, Kohn posed the question “Is our software good enough?” and then answered it by declaring, “No.”

Part of the issue is that while there are many potential benefits to making the transition to microservices, older tools for things like communicating between applications and monitoring app performance won’t work in this environment. That same LightStep survey found that 99 percent of developers surveyed reported some “challenges” in using microservices, with more than half saying it was increasing their operational challenges.

This begs the question: Is the move to microservices simply trading an old set of problems for new ones? Put another way, will the promised benefits significantly outweigh the headaches?

Sigelman says the answer is yes, noting that the new architecture can potentially reduce the risk of a single failure bringing down someone’s entire system.

“The operational efficiencies will be there regardless,” he said. “You’re going to get rid of some really profound problems.”

Of course, that’s also an opportunity for people like Sigelman, whose company is making tools to solve some of those new issues. And indeed, that was true of many of the startups on hand, as many of the product announcements were aimed at plugging those gaps and bolstering the overall maturity of this approach.

Still, conference organizers sought to infuse the gathering with a greater sense of urgency right from the start.

Alexis Richardson, founder and CEO of Weaveworks and a CNCF board member, kicked off the conference by issuing a challenge to the audience. The wave of excitement around this market had propelled their movement further and faster than anticipated, he said. But adrenaline wasn’t enough. With more attention and more interest being showered on cloud native computing and microservices, the movement needed to grow up even more quickly and make sure all the pieces are in place to deliver on its hefty promises.

“Think of CNCF and those first couple of years being like a startup,” Richardson said. “The startup phase is over.”

(Disclosure: The Linux Foundation paid for VentureBeat’s travel expenses to Copenhagen for the KubeCon + CloudNativeCon Europe 2018 event. Our coverage remains objective.)