Rumors of email’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. While the “age-old” communication conduit may have new rivals, it is showing little sign of letting up.

In 2017, active email users stood at 3.7 billion globally, a figure that’s expected to hit 4.1 billion by 2021, according to research firm Radicati. Last year, nearly 270 million emails were sent each day, and this is expected to grow 4.5 percent to 280 million in 2018. Messaging and VoIP apps may be popular, but email still has a crucial role to play, particularly in longer-form communications and in the B2B and B2C realm.

SendGrid, a well-funded email delivery performance platform, went public on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in November at $16 per share, and its shares have been riding at around 75 percent over its IPO price in the months since.

Venture capitalists continue to bet on email startups, as well. Front recently raised $66 million from big-name backers such as Sequoia and DFJ to grow its email collaboration platform, while Sigstr raised $5 million for a tool that lets companies transform email signatures into advertisements.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Elsewhere, Google gave Gmail a major upgrade a few weeks back with a big focus on security and productivity, while at its I/O developers conference this week the company announced a new AI-powered Smart Compose feature for faster emailing. Microsoft followed suit with a bunch of new features for Outlook.

People may moan about email and wish it consigned to the fieriest of fires, but all signs suggest it’s here to stay. That’s not to say the technology won’t continue to evolve, however.

Against this backdrop, one Swiss company has been making inroads into the email realm over the past few years by putting privacy front and center.

The birth of ProtonMail

Founded out of Geneva, Switzerland in 2013, ProtonMail was the brainchild of Andy Yen, Jason Stockman, and Wei Sun, academic researchers working on various particle physics projects at CERN — where Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web a quarter of a century earlier.

ProtonMail promises its users full privacy via client-side encryption, which means nobody can intercept and read your emails. Not even ProtonMail itself.

Above: Headquarters of Proton Technologies AG in Geneva, Switzerland

ProtonMail first came to attention in May 2014 with its official public beta launch on the web. (Incidentally, it had to close sign-ups soon after due to high demand.)

The following month, the company launched an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign with the goal of raising $100,000. Shortly into the campaign, however, PayPal cut off funding after raising questions about whether ProtonMail was legal and had “government approval to encrypt emails,” according to Yen. After a minor public furor, the restrictions were lifted and the company went on to crowdfund more than $500,000. Several months later, ProtonMail received an additional $2 million cash injection from Charles River Ventures (CRV) and the Fondation Genevoise pour l’Innovation Technologique (FONGIT).

Following a series of iterative launches, ProtonMail officially shed its beta tag in March 2016, launching to the world with Android and iOS mobile apps in tow.

Yen, who serves as CEO, is the only member of the early founding team who is still active in the leadership of the company.

A curious facet to the ProtonMail backstory is that the product is often associated with CERN because, well, CERN is where the founders met and developed the product. But it wasn’t a direct result of any particular project that they were working on at the time.

“I was actually a researcher working on supersymmetry at the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider,” Yen told VentureBeat in an interview. “Thus, ProtonMail was actually not at all related to my PhD topic. However, some concepts such as software design, mathematics, and large scale computing did carry over.”

CERN is perhaps better known for its work in the physics realm, with the Higgs boson particle discovery garnering global headlines and the Nobel prize in recent years. But as the birthplace of the web, computer science also plays a big part in its research curriculum. So in that respect, ProtonMail was very much a product of its environment.

“CERN actually does significant research in the field of computing, so my natural curiosity into the topic, plus the large number of experts in the vicinity that I could discuss with, gave birth to the idea,” Yen added. “Building ProtonMail was initially just building a tool that I myself wanted, and it just happened to turn out that — after it was built — millions of others also wanted something like this.”

The genesis of ProtonMail was a culmination of factors rather than a specific “a-ha” moment for Yen et al., and the company’s founding came at a time when the words “hacking” and “surveillance” were rarely out of global newspaper headlines. This was largely due to whistleblower Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations, which gave prominence to an encrypted email service called Lavabit that Snowden had used. Lavabit was soon forced to shutter following pressure by U.S. authorities to grant them deeper access to Lavabit’s systems.

Lavabit relaunched a few years later, shortly after Donald Trump entered the White House, but the technological landscape had shifted. People were more savvy to surveillance, and companies had taken note — both Facebook Messenger and Facebook-owned WhatsApp had introduced encryption in mid-2016. And a year later, Google announced it would no longer target users with advertisements based on the content of their Gmail accounts. That didn’t concern encryption, but it was a tacit acknowledgement that people were becoming increasingly sensitive about their privacy.

Lavabit’s closure in 2013 was preceded by gag-orders, search warrants, and subpoenas, prompting owner and operator Ladar Levison to state [emphasis ours]:

This experience has taught me one very important lesson: without congressional action or a strong judicial precedent, I would _strongly_ recommend against anyone trusting their private data to a company with physical ties to the United States.

And this was the world that ProtonMail entered back in 2013, except it held a trump card over its predecessors and rivals: ProtonMail’s data centers are based in Switzerland, and Swiss privacy law is considered among the strongest in the world, which is a big selling point to prospective customers. But over and above all that, ProtonMail was positioning itself as the ultimate privacy-focused email platform.

“The idea of making end-to-end encryption completely automated and widespread really hadn’t been attempted before in a serious way, so it was quite exciting to try and attempt that,” Yen said. “There was also the realization that the world wide web itself had transformed into something quite different from what its creators intended. With the information superhighway came a massive surveillance apparatus built by private companies, and misused by governments, that was posing an existential threat to democracy, and nothing was being done to reverse this trend.”

Data protection

Back in March, ProtonMail was briefly elevated into the Cambridge Analytica data scandal that had engulfed Facebook — it transpired that Cambridge Analytica had used ProtonMail due to another of its core security features.

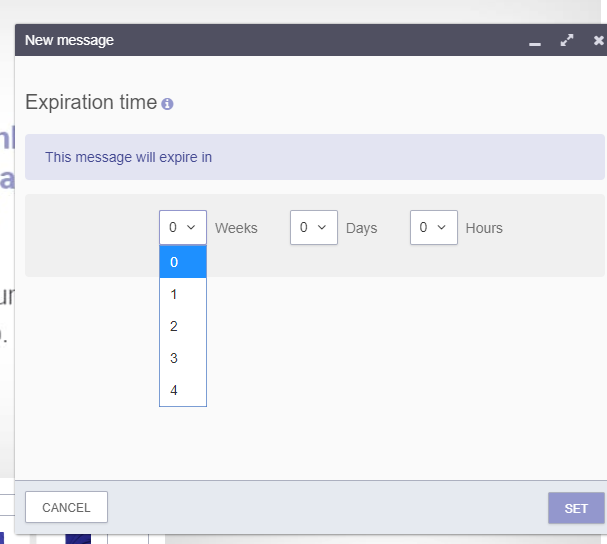

You see, encrypted email platforms are only useful when emails are in transit between accounts. There is nothing stopping sensitive information from leaking through scrupulous phishing techniques or good ol’ fashioned poor password hygiene. As such, ProtonMail offers an email expiry feature that lets the sender dictate how long an email is visible to the recipient.

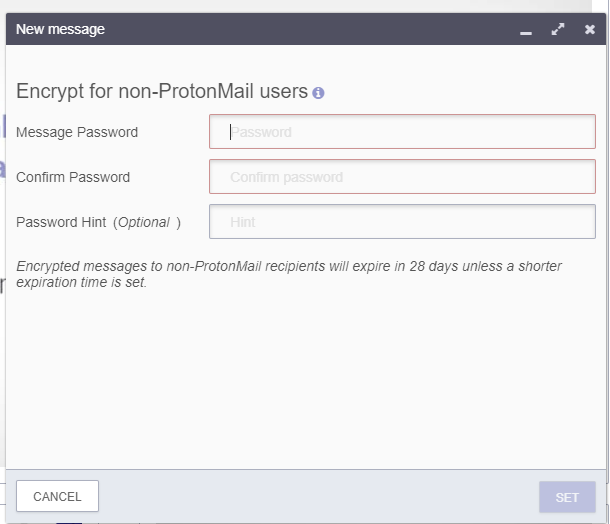

It’s like Snapchat for email users: ephemeral messages that the sender controls. But ProtonMail goes one step further by allowing encrypted messages with expiry dates to non-ProtonMail users too. So if you send an email to a Gmail user, for example, you can hit the encryption button and require the recipient to enter a password to view the message.

Above: Encryption for non-Protonmail users

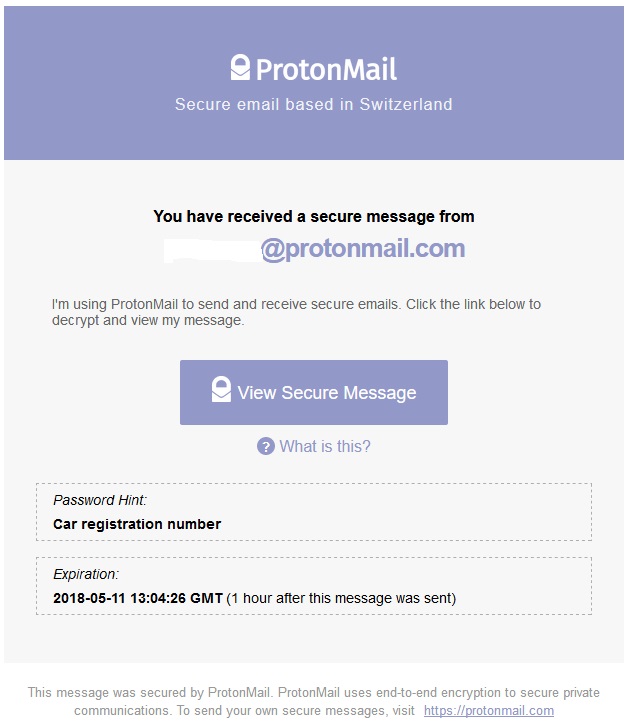

The recipient can guess at the password based on a hint you provide them with, or you can send them the full password via another means, such as SMS.

Above: Encrypted message

Google unveiled a major revamp of Gmail a few weeks back, and one of the new features leans heavily on this concept. “Confidential mode” will allow Gmail users to send emails that automatically expire after a set period of time, while an optional two-factor authentication (2FA) feature requires the recipient to enter a passcode to read it.

Some might argue that ProtonMail is setting the standard for email privacy, and as its name becomes increasingly entwined in major news stories, it will likely gather more users too. In the wake of Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. election in 2016, a number of VPN and encrypted messaging services reported a spike in downloads, including ProtonMail. So did the Cambridge Analytica association have any positive impact this time around?

“As we become more popular, we also end up with more prominent users,” Yen said. “Recently, some of the users which have been identified by the media include the White House and Cambridge Analytica, and of course coverage like that does lead to short term spikes in signups. However, it’s the broader trends that really drive long term growth.”

These trends include the deterioration of legal frameworks in certain countries in relation to free speech and oppressive regimes, which drives people toward privacy-focused communication tools. Also, a growing awareness of ad-based business models and the implications they have for personal data. “The Facebook scandal was a good example of that, and this increasing awareness among consumers leads more of them to seek out services that put privacy first,” Yen added.

Speaking of which…

The business

An oft-repeated mantra by privacy advocates relating to online services is that if you’re not paying for the product, you ARE the product. This issue reared its head again in the wake of the recent Facebook privacy debacle, though Facebook maintains that its users are certainly not the product. Whatever your position on the issue, there is little question that if you pay a company hard cash for their wares, then you are — at the very least — less of a product. You pay money, the company gives you a product. Simple.

ProtonMail has gone to great lengths to explain how it’s more secure than the likes of Gmail, but it basically boils down to one thing: With ProtonMail, you own and control your data, whereas at Google your data is the currency with which you “pay” for its services.

ProtonMail does offer a free service, but it has major restrictions on things like storage capacity and the number of folders you can create — it’s more of a carrot-and-stick to get you to check the service out and upgrade to one of its paid plans, which start at $5 per month.

Some of the paid plans may be more appealing when juxtaposed against the company’s push beyond emails.

Beyond email

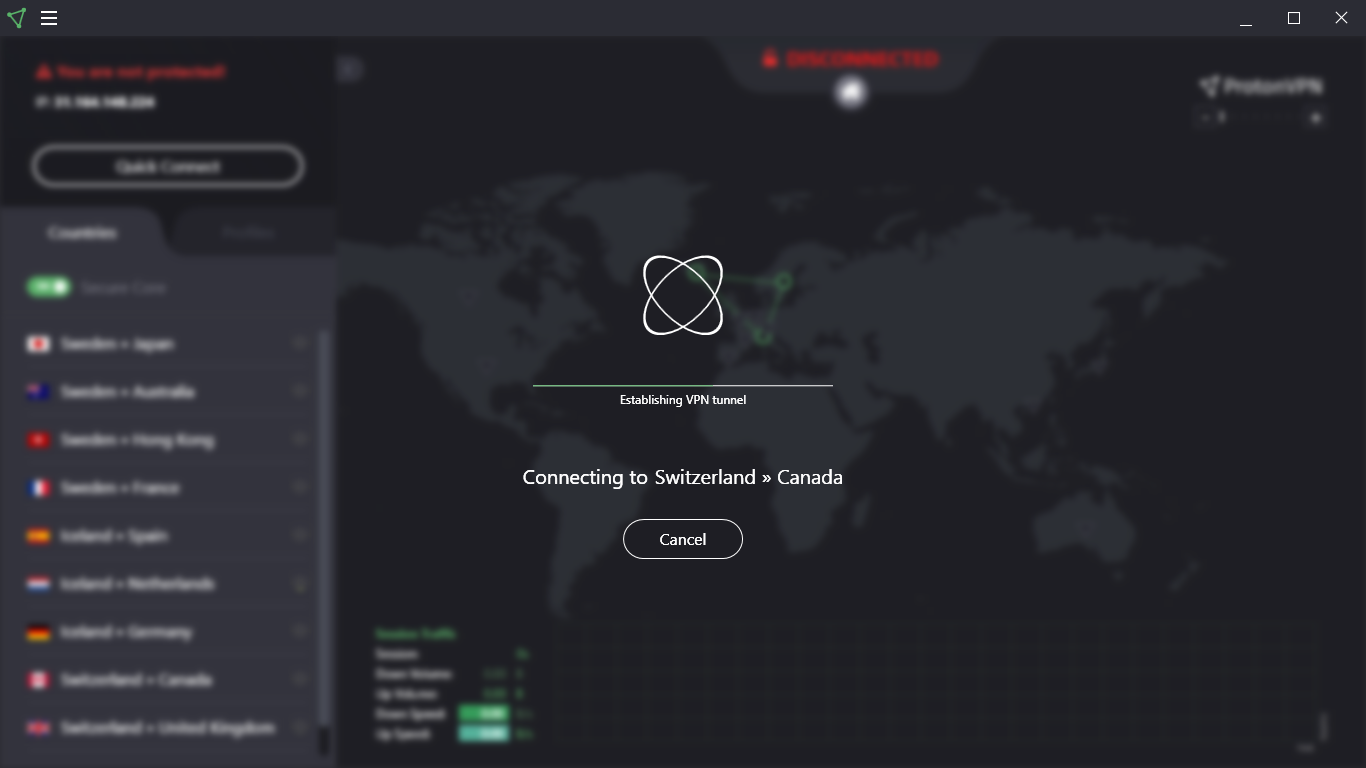

Though ProtonMail regularly rolls out updates to its core email service, including support for 2FA, Tor, encrypted contacts, a shorter domain name, and desktop email clients, it’s also branching out into related privacy verticals. Last year, the company launched a standalone virtual private network (VPN) service called ProtonVPN, which is available for free (with limitations) or a separate subscription. However, those who subscribe to a ProtonMail “visionary” plan at $30 per month / $288 per year get the full-featured ProtonVPN gratis. And this hints at where ProtonMail is going.

Above: ProtonVPN

Email’s demise has been predicted for decades, but — as we noted earlier — it’s still going strong. ProtonMail has built its business on the basis that email will continue to thrive; however, it is exploring complementary businesses that feed into it. It doesn’t want to be a one-trick pony.

“The death of email has been predicted since the mid-’90s, and each time email has survived and we think email will continue to survive,” Yen said. “By being fully federated, it’s actually the most popular communication system ever conceived and can never be monopolized. As a company, we are about more than email, however, and forays into VPN and other sectors are not random, but part of our longer term strategy to provide consumers and businesses worldwide a secure and private choice, in contrast to the many existing web productivity products that exist today.”

So what does this mean, exactly, in terms of product roadmap? An obvious next step for ProtonMail would be to head where all the cool kids hang: the land of messaging apps. Yen was non-committal on that specifically, but he certainly didn’t rule it out. What we can expect to see, however, are products similar to what have sprung up alongside Gmail, such as cloud-storage services and productivity tools.

“In this regard, we are largely following the demands of our community,” Yen said. “In the near term, this means Calendar and Drive, but in the long term I think we will cover a lot more than that.”

So what we could end up with is a business that includes all manner of cloud-based products, similar to G Suite, available separately or through a single bundled subscription. Such a setup would also enable ProtonMail to lure in more customers, particularly from the business fraternity whom the company is already courting with its professional subscription tier that offers centralized admin account controls.

ProtonMail wouldn’t divulge any clients, but did say that there are “tens of thousands” of businesses using the service, covering multiple industries. “Users range from governments to Fortune 500s to NGOs working in the field,” Yen said. “It really shows that increased online security is something that is needed across a broad spectrum of industries.”

A numbers game

Today, ProtonMail claims more than 5 million users, though Yen wouldn’t reveal how many of those are on a free plan. It also counts more than 50 employees around the world — 80 percent of whom live in Europe.

ProtonMail has raised relatively little outside funding compared to other startups, and this ensures that it is under less pressure to chase a big exit. Moreover, the company is already profitable, which bodes well for the future. “Profitability is a matter of security and reliability,” Yen added. “We also maintain significant reserves in case of unexpected expenses.”

However, to fund a major expansion may require significantly more money, which is why it is considering taking on more outside cash — but Yen said the VC model probably isn’t the best fit for its purposes. “We would have to innovate in this area,” he said. “We’re currently looking into this, but haven’t made any final decisions yet.”

The company remains controlled by its employees, and it plans to keep the company independent.

For now, ProtonMail’s servers remain entirely in Switzerland, but as the business grows, the company may have to expand its footprint elsewhere. “We are also considering adding datacenters inside the EU as we have gotten requests from some of our European customers,” Yen added.