Dementia affects more than 60 million Americans. And today, on Christmas day, many will realize at family gatherings that their elderly relatives have gotten worse at remembering things. I know this well, as my 85-year-old mother has dementia, a loss of cognitive function which causes memory loss and other symptoms.

I’ve been spending some time talking to experts about it, and how we can turn to technology, medicine, or even games to stave off what seems inevitable as our bodies start to outlive our minds. Too often, I’ve found that tech products have been designed without the needs of older people in mind.

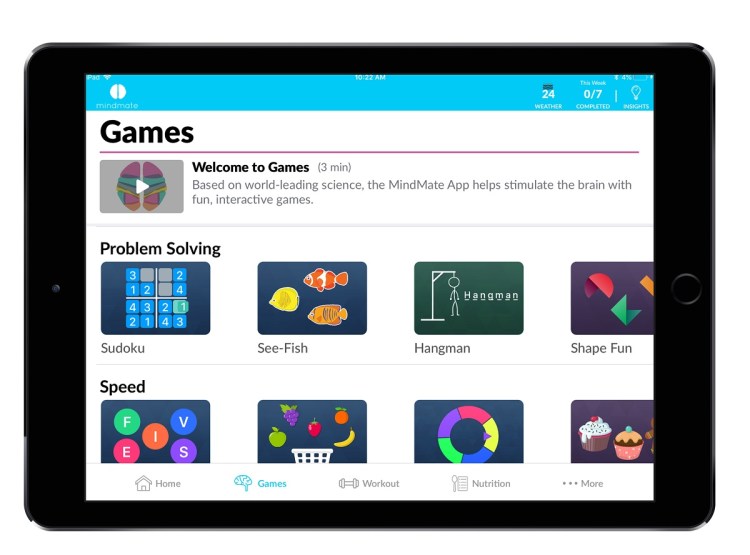

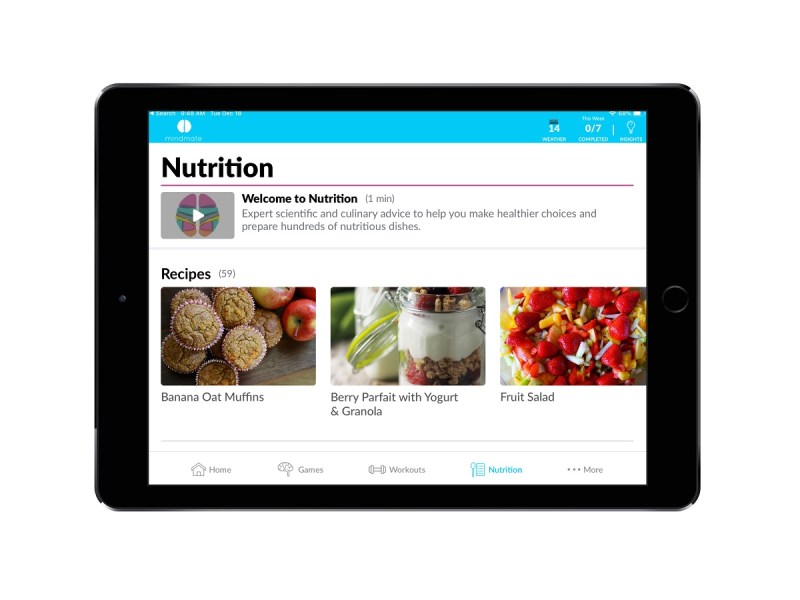

Clover Health, a health care technology company with a mission of helping its members live their healthiest lives, is one of the companies trying to improve mental skills for the elderly. They recently established a partnership with the team at MindMate App. The app combines brain games, healthy nutrition, regular exercise, and social interaction. It encourages its users to make multifaceted, holistic lifestyle changes to help stave off the effects of cognitive decline.

I spoke with Matt Wallaert, chief behavioral officer at Clover Health, about Clover’s approach of using a proprietary technology platform to collect, structure, and analyze health and behavioral data to improve medical outcomes and lower costs for patients. Through its partnership with MindMate, Clover is able to monitor participating member’s app activity and alert the Clover care team of any significant decline in cognitive performance. This can significantly improve health care providers’ and caregivers’ ability to recognize Alzheimer’s, stroke, dementia, and other neurological disorders early, Wallaert said.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

I’m sure that’s interesting for a lot of people. But I had a good conversation with Wallaert, in part because we wandered all over the landscape of what it means to deal with the aging of our brains. I hope you enjoy it, and Merry Christmas to those of you who celebrate it.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Matt Wallaert, chief behavioral officer at Clover Health.

GamesBeat: Tell me more about MindMate.

Matt Wallaert: It’s a company we’ve started spending more time with. We’re launching a little partnership and exploring how gaming can help our members and power some interesting interventions.

GamesBeat: My own mother, who’s 85 years old, has dementia. It’s a very relevant topic for me personally.

Absolutely. I was talking to someone at Clover about this the other day. It’s so relevant as we go into the holidays. This is when a lot of people come home for the holidays and see some of their relatives they haven’t seen in a while. They may not have realized how much has changed since the last time they saw that person.

That’s one of the reasons we’re excited about our work with MindMate. If we can do that early detection, so you don’t show up for Christmas and suddenly realize that she isn’t mentally where you thought she was — if we can detect that earlier on and start to coordinate some of that social support, it can be a real benefit to families.

GamesBeat: How do you do that?

Wallaert,: MindMate is a brain games-focused app. It’s pretty engaging. One of the things I liked — if you look at the average health app, it’s about 3.5-minute session times. They’re not very engaging. MindMate is more like a 16-minute session length, much more like a mobile game.

That entertainment focus is interesting for me as a scientist, because one of the dominant problems has always been how you motivate people to do things. With MindMate, they’re doing the motivation. We can piggyback on the data. People play three to five times a week for 16 minutes at a time. That generates a lot of cognitive data that we can then use to benchmark someone against themselves. We can see if you’re declining over time. That might be a sign that you need to have one of our nurse practitioners have a conversation to check what’s going on as we go along.

The app is pitched like a lot of brain game apps. Memory, reaction time, all of those things people actually like doing on their phones. They’re fun. If you look a lot of modern games, they’re just presentation layers on top of very traditional game mechanics. Those mechanics yield interesting data. The app feels very traditionally like a game, but because games stretch our minds, it does provide good cognitive data.

Above: Dean Takahashi and his mother Hiroko.

GamesBeat: I wonder about gamers’ mental decline over time. Everyone likes to point out that I’ve been playing Call of Duty for years, but my reaction time is so much worse now that I can’t beat the kids who shoot me online. It’s a bit of a digression, but I wonder if that can tell you anything.

Wallaert: It goes in both directions. When you talk about twitch gaming, something like Call of Duty, where reaction time is incredibly important–there are peaks in reaction times. When you look at the science, when you’re 85, you might be able to say that your reaction time is the reason you can’t beat the youngsters. Earlier than that, you may just have other things on your mind besides playing games 24/7.

On the flip side of that, one of the things I love about games, whether electronic games or board games or card games, they have all those mentally protective features. Even if you think about something like bridge clubs, what does that do? It gets you around other people. It gets you talking every day. There’s mental math and accounting that goes into even simple card games. I like pinochle, because I grew up with it. A kind of poor man’s bridge. The cognitive piece can be a protective factor against dementia and other things. It’s the continued use and engagement of your mind.

Games exist along a spectrum. Some games are a bit mindless compared to other games. But being engaged, finding gaming as a place where we can engage people’s cognition, is really exciting.

Above: Humm has a headband for esports biometrics.

GamesBeat: There’s always some kind of hope that my skill can improve. I don’t know how much age matters there. Another digression, I got this headband from another company, Humm, that sends electrical signals into your frontal cortex there. It’s supposed to stimulate your reaction time. I haven’t noticed if it works yet, but it’s an interesting idea.

Wallaert: The thing that’s always interesting about those types of devices — it goes back to the motivational piece. Even if we found something — look, I can’t even get to the gym. There are no things that are good for you that aren’t difficult to get people to do, because they’re uncomfortable, or they take time.

What I love about games is they’re intrinsically engaging. The great thing about working with MindMate is that normally my team spends an enormous amount of time on that motivational piece. How do we get people to want to do something that’s good for them. Games are self-motivating. You want to play. But they’re also quite good for you.

If you take something like MindMate — we have a large machine learning team, and one of their big outputs is something called diagnosis suspecting. How do we take in all the data we have about a person and say, “What might be going on with them that the conventional medical system has not yet recognized?” At this point we’re able to make significant new diagnoses that we can then confirm in person.

We have all these NP/MA pairs that go out. The system says, “Based on all the signals, Matt might be pre-diabetic. When you see Matt in person, have a conversation about diabetes.” Because we have a connection to their doctors, we can also, in the app that we use, tell their doctor: “Hey, Matt might be pre-diabetic, so when he comes in for a checkup have that conversation.”

What we’re working on with MindMate right now is taking in the data from this rich source. I intrinsically want to play games. I don’t have to do anything I wouldn’t normally do. I can just do something that I enjoy. But then that yields data we can plug into a machine learning algorithm and say, “Next time Matt comes in, you should check and see what’s going on. His reaction times are going down. He’s starting to not perform as well at short-term memory tasks.”

It’s that alerting system that — even separate from, to your point, the question of whether these games make you smarter. It’s possible. There’s some good evidence that brain games and staying engaged mentally is good for you. And then on the alerting side, even if you don’t expect the game to improve your mind at all, we can still derive value from understanding what’s happening with you and being able to intervene within the normal clinical system.

GamesBeat: Is there a stage or an age where you think it’s good to get this started, to be able to detect things happening with people? There’s a certain stage where it seems like it may be too late to be helpful, but I don’t know exactly what that might be.

Wallaert: On the detection side, and even on the brain training side, people being engaged at any age is great. We can always make use of that data. You’re right on — at some point, your cognition has declined enough that I don’t think playing games is an effective way of combating that. Although there is anecdotal evidence out there that just being engaged in the world can be quite good.

On the learning side, even if at this point you’re quite demented — if your cognitive abilities have slipped quite far — even the alerting piece is quite good. Recognizing what’s going on with people seeing sudden decline. Even if the game can’t improve you, there are nice pieces to that. In a perfect world, where you and I got to design our Star Trek game of the future — if there was a game that followed you through your whole life, there are some very real potential possibilities there to be able to take longitudinal data.

Think about it this way. If you start playing the game, that’s my first detection point for you. I can watch if you decline after that, for sure, but I don’t have a long history. Whereas if we can get people playing brain games earlier and earlier on, I know what you’re normally like, and I know what you’ve been like for a long period of time. I can detect more subtle changes. The longer the history of data I have, the more subtle the changes I can detect.

Above: The MindMate app encourages good nutrition.

GamesBeat: If you could get any data, what would be your sort of dream data for your purposes here, detecting mental decline?

Wallaert: That’s a hard question. Some of the MindMate data — certainly reaction time is really important data when we start talking about cognitive things. It’s a good kind of canary in the coal mine for other stuff that might be going on. If you think about what happens in reaction time — as long as it’s not purely automatic, the autonomic nervous system — many steps of cognition happen there. Often reaction time to language-based things is really good. Lots of parts of your brain are involved in processing that data. It’s a good end-to-end detection mechanism.

Memory is also good. I love some of the memory games that are available for that same reason. The ability to hold something in mind is also one of the things that — when it goes, it’s not always transparently obvious. Looking at stages of dementia, it can be hard to tell the difference in someone who’s genuinely abnormal, as opposed to the normal forgetfulness we all experience. We all sometimes struggle to remember the name of a song or something. How do you detect those changes?

I will say that in many ways, it isn’t just about the data for me as much as it’s also about the ability to then go intervene. Much has been made of big data. Everybody’s gone and put together giant data lakes and tried to make something out of that. But it’s not helpful if you can’t do something about it. The ability to have an on-premise nurse practitioner and medical assistant pairing that can go out to somebody’s home and say, “Hey, let’s check in.” Having a field outreach team, having close connections with doctors — it’s the full intervention loop that’s really interest. Data alone doesn’t do it.

MindMate has the same data. Intrinsically it has all this data. But they don’t have the ability to send someone to intervene, and we do. That’s why the partnership makes sense. You have to have that full loop. It isn’t just about data for me. It’s about the dream system of being able to take that data and say to a doctor, “We saw this and you should check in on this the next time they come in,” when they might not normally do that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDVUAdxsg7Y

GamesBeat: I interviewed John DenBoer recently. He has this company called Smart Brain Aging and the BrainU online app. It’s a competitor of sorts, another set of games for people with early dementia signs to play. One thing he said was interesting, though. He looked at some of the other games out there, like Lumosity, and he noted that a lot of their games were very repetitive. They would give the player the same kind of quiz each day.

He argued that if you make someone use the brain in a different way every time they come back, that was a positive. You could otherwise see them get into a pattern where they only get better at one particular thing while the rest of their mind could still be in a state of decline. Sort of like, if you do a lot of crosswords you may get very good at crosswords, but your mind might not stay so sharp in other ways.

Wallaert: I’d push back on him a little bit on that one. What he’s talking about, essentially, is the practice effect. The longer you do a task, the better you get at it, for sure. There should be, in theory, for any task — the more we do it, it should go up and to the right. He’s saying that up and to the right might disguise a larger general decline.

But remember, when we talk about something like dementia, we’re talking about a neurological, biological decline. It’s unlikely that the practice effect would mask it, and even if it did, you’re not going to see substantial enough practice increases.

GamesBeat: The masking part may be me misspeaking somewhat. It’s more that the games you play repetitively and the things you use your mind to do repetitively don’t necessarily help you stave off further decline.

Wallaert: Certainly there’s an idea that neurodiversity — the more different kinds of tasks you do may be protective. All of this is still in the very early stages of science. In some ways we’re still the blind leading the blind, in the sense that even neuroimaging at this point — if you’ve ever watched an FMRI or another type of imaging process, we’re in the very early days of being able to detect what goes on in the brain. The brain is a fantastically complicated thing.

You could certainly posit that doing different kinds of tasks might keep you sharper. That seems generally probably true. But I think that sometimes, particularly among people who are really invested in the “games improve your brain” business — they overstate the case or the evidence available there. What’s certainly true is that games are good at recognizing or providing data that might alert us that something has gone wrong.

This has always been — Lumosity makes very bold claims about what they are able to do for people’s brains. But when people investigate those, there’s been more smoke than fire there. That said, again, the detection portion is actually a little bit easier for us to measure, because can say, “Hey, we think we’ve detected a change.” Then we can follow up with more extensive, more in-depth clinical testing and see if that matches the detection we see in the changes in data.

Part of that is just habituation. Computers are good at doing something we’re bad at doing. I’m a psychologist, right? One thing we’re bad at as humans is we habituate. It’s not like Grandma loses her memory all at once. Every day it just gets a little worse. That’s why I talk about the holidays. If I haven’t seen you in a long time and then I see you, it’s evident to me how much has changed, whereas if I’ve seen you every day, I might not realize because the decline is a little at a time.

The great thing about allowing algorithms and data to guide us, that can say, “Hey, you’re not recognizing this, but it’s really happening, and it’s happening steadily. You need to go address it.” It’s that human-AI hybrid that I think is so powerful in terms of the detection portion.

Above: MindMate encourages exercise for older adults.

GamesBeat: As far as more deliberately designing something for this purposes, how is it different from designing, say, a trivia game, something that isn’t necessarily intended for dealing with dementia?

Wallaert: One of the problems of games in general is that they’re often unimodal. They’re based on a central core conceit. Part of the problem of nerve degeneration is it’s short term memory and long term memory and reaction time and, and, and — there are so many pieces to it, and you really do need a suite approach to that. That’s some of what I would see eye to eye with DenBoer on, the notion that you need more than one triangulating point in order to do good detection.

When people try to take data from a unimodal app, it’s a very impoverished signal. Even MindMate on its own, or Clover on its own — it’s the triangulation of multiple signals that helps. Reaction times are slowing down. Memory is getting worse. They haven’t called Clover in the last several months. They’re going to the doctor less but their medical expenses are rising. It’s a whole combination of factors that says there might be something going on and we can do early detection. When people try to just use naturally generated data from games without designing the games to generate that data, I do think there’s often not enough meat on the bone to be able to intervene in a timely way.

GamesBeat: Trivia Crack or HQ Trivia, then, that’s not going to be as helpful as something more deliberate.

Wallaert: Absolutely. Now, I still think we’re in the early stage of what “deliberate” is. I don’t think anyone has cracked the code and figured out that this or that modality is going to be the perfect thing. But we know enough to know that it needs to have a component of reaction time. It needs to have a component of memory. We’ve started to tease those out.

GamesBeat: If you look back into history, are there games that share some of these characteristics? I don’t know if it goes all the way back to Nintendo’s DS Brain Age game.

Wallaert: I remember that one well. There have been — even for the Game Boy there were brain-based games. One of my favorites, actually — if you want to get really old on this, it’s Tetris. It combines reaction time with spatial awareness. I don’t think anyone’s done this, because there’s no way of getting the data. I don’t think anyone’s tried to look at it. But I would bet that Tetris performance is probably a pretty reasonable early warning sign that there might be something going on neurocognitively, if we saw that decline.

Honestly, lots of the games we make for children — this is not meant to imply that dementia makes people childlike or in any way deprives them of what it means to be an adult. But we make games that help push kids’ cognitive envelopes. Slapjack, something that has that reaction time element to it. I have a three-year-old and I watch him getting better and better at memory games, remembering where the cards are and flipping them over one and a time and turning them back. Even if those were designed to push the neurocognitive envelope, they’re inadvertently pretty good tests of neurocognitive things.

To your point, there is some accidental good detection out there in the way we’ve made games throughout history. What I think is new in this area is combining modes of games, and then being able to get data out of them. Something that has the internet as a backbone, smart apps, that kind of thing that can give you the data output. And the real new revolution is then marrying that data to other things. As I pointed out, the data alone doesn’t do a lot. It’s the ability to match that data up to what Clover has — a clinical data set, a stream of claims, knowing when you go to the doctor, talking to you often, seeing you in person. Marrying all that together is where I think starts to get interesting.

The next frontier is starting to involve families more. Not just being able to alert a doctor that you should do a neurocognitive test the next time a person is in the office, but really starting to involve families in the care of older adults as they age, by helping them start to do some of this detection work. Getting their opinions. “Hey, have you noticed anything going on with Grandma the last time you saw her?” Honoring that small data is as important as getting it together with all the big data.

Above: Hiroko Takahashi

GamesBeat: From your experience, is it very helpful to catch this early and to do preventive work? Or is it inevitable?

Wallaert: The perception that it’s all over, unfortunately, is something that makes it worse. As we all know, we’re heavily affected by our own meta-cognitive states, our own feelings. I muse about this all the time. I make my living with my brain. I’m a scientist. I’ve been doing this for a long time. I think about what it would be like if I had a stroke or an accident, something that affected my cognitive abilities, and how core that is to my personality and my identity. It can be quite hard.

When I went to Swarthmore in college, all of my family was back home in Oregon. I was a first-generation college kid. I didn’t really know much about going to college. I was sort of adopted by this older couple that had retired from the college. He was a VP of development. Unfortunately, both of them have passed in the last couple of years. They were so smart and so vibrant for so much of my time with them, and then watching them toward the end, their neurocognitive decline and how that affected them emotionally, was really hard.

That’s actually one of the reasons the MindMate partnership is really interesting to me. I don’t just think it’s about neurocognitive protective factors, although I think those are real. To me there’s also social support stuff. The sooner your family can help you create an environment in which the difficulties you’re having won’t be a danger to you or to others, that’s a great thing. The earlier we set that up, the smoother the transition we can have.

GamesBeat: What about the notion that I don’t have to worry about this for a long time? How early should people start thinking about playing with this kind of purpose?

Wallaert: I think it’s never too early, but what I would say is, that’s challenge to developers. That’s a challenge to game designers everywhere. Hopefully what we get to is a place where you don’t have to play a game that you don’t really enjoy, because you feel like you need to take it like medicine. Instead we create a variety and a diversity of games that meet people where they are, that are based on their interests.

I think about Monopoly. Monopoly comes in every flavor known to man these days. No matter what you’re interested in, there is a version of Monopoly that does it. The core game is the same, but it’s hooked to some cultural element that resonates for you, and that’s enough to get you to play. What’s interesting to me over time is, how do we make enough games in the world that — you don’t have to feel like, well, it’s too early or too late to start. Instead you authentically want to engage with it because it’s fun.

There’s a million registered users of MindMate, and I don’t think it’s off the value proposition of “defend my brain against aging.” These are games. They’re designed for you. They’re fun. The print is large. It’s based on fun. Then the challenge to the rest of us is, can we take the thing that’s authentically fun, authentically motivating, and then add value to it for you? Can we make this thing you naturally want to do something that’s good for you?

I think a lot about laser tag. Laser tag is an amazing way to get people to exercise without thinking about exercise. They play because it’s fun, because they’re with their friends. But if you ever play an intense game of laser tag, you’ll be very tired at the end. You’re running around playing laser tag for an hour, that’s an hour of running. People will do it who would never go running on their own. That’s the attraction of games. How do I want to make something that you just want to do, but that’s actually good for you?

GamesBeat: Do you see much activity being pushed by the insurance companies in this area?

Wallaert: At Clover we try not to over-anchor on what other insurance companies are going, because other insurance companies — I don’t think that insurance companies have always done a good job of focusing on member-centric profitability through health outcome models. But that’s one thing I like about Medicare Advantage. I do think, at least in the Medicare Advantage space, you will see insurers start to lean in.

I hope they choose to follow our example, because there’s nothing but net good for our society for everyone to get together. Insurance companies, game designers, everyone involved can lean into making people able to live a healthier, better life.

GamesBeat: Like a wellness program.

Wallaert: Yes, but embedding wellness in everything. I think wellness programs, explicit wellness programs, certainly have their target audience. But I have a three-year-old. I don’t get to the gym as much as I’d like. When it’s explicitly about exercise, explicitly about that wellness program, I’m not sure it really gets us there.

Instead, I think it’s incumbent on insurance companies and the medical field to get where people are. Instead of saying, “Come to me,” say, “I’m going to meet you where you are. If this is the game you want to play, play it, and I’ll figure out how to get what I need out of it to be able to help you.” That’s incumbent on us. That should be our burden, not the member’s burden. The goal of Clover, the goal of good progressive insurance, is the idea that people are able to do the things they would normally do, normally want to do, and then we find a way to do them in the way that maximizes their health outcomes.

At Clover we collect personal health goals. In your own words, why do you want to be healthy? What’s important to you? If you say to me, “The most important thing in my life is grandkids,” great. That’s how we’re going to orient your care. We’re doing a thing right now around flu shots. If that’s the thing that motivates you, we’ll harness that motivation for a health outcome that’s good for you and that you care about. We’ll connect those things together.

The member’s self-expressed health outcome, health goal, should be the primary focus of medicine. That’s where we see insurers going, or at least it’s where we’re going. Understanding what people mean when they say they want to be healthy, what their motivation is for that, and then honoring those motivations. Doing the work ourselves to design an environment that takes advantage of those motivations to improve their health, that helps them be where the want to be, how they want to be, in the right way.

GamesBeat: How far do you want to go toward clinical studies showing that this has benefit?

Wallaert: I’d certainly be open. We have a chief science officer, who I partner very closely with, and we’d be open to generating novel clinical data, a novel clinical study. That’s something we do at Clover and that we’re comfortable with. But I don’t think that’s the place to start. The place to start is the piece I was talking about: do members like this? Do they want to play these games? Are they okay with us having this data? Do they want us to give them feedback on what’s going on?

It’s less about, right now, whether this game improves people’s mental health clinically. It’s more about seeing if it fits into people’s lives. If it does, then we can start to understand if it’s good for them, if there’s clinical benefit. But the data is immediately beneficial. That’s something we can take and start to immediately tune into our algorithm to see what novel — is it additive to the model in a way that allows us to take care of someone in a better way? I’m open to a clinical study, but that’s not the standard for me. The standard is, can I derive member benefit from it?

GamesBeat: Something like 60 million people at this point have dementia, right?

Wallaert: Dementia is a very clinical term. All of us inevitably, as we age, experience some of the neurocognitive declines of age. Whether that crosses all the way over into dementia or Parkinson’s, or if that stays on the other side of the clinical diagnosis line but still remains very real — either way it affects all of us. If we’re younger, well, we have family members. We have people in the world that we care about struggling with this. One of the reasons it’s so interesting is because it’s so ubiquitous.

Above: Paula Kreisser is a Clover Health member in Savannah, Georgia.

GamesBeat: Is there a trove of data that you have over, say, one year or two years that you’d like to see from a member? How would you be able to make use of that?

Wallaert: Mostly we’ve focused on what we would call within-subject design. That means I’m looking at Dean’s scores over time and trying to attack Dean’s decline over time. Certainly there are between-subject studies you can do as well. As enough people participate and you can watch the decline of various people, that starts to get really interesting. Are there predictable declines? Do they map to demographics? Do they map to signals that MindMate has about people’s activity levels? Do they map to signals Clover has about people’s clinical data? We know what else is going on.

Again, as we talk about this, the brain is not super well-understood. Our ability to recognize and classify these diagnoses is new. By incorporating the data with other data, you can do really interesting things. For example, is dementia worse in the north or the south? Are there demographic considerations? You can get hyper-local. Is dementia getting worse or better over time?

One of the problems we often have is that a lot of data sources are clinical data sources by nature, meaning someone gets a diagnosis of something. But when you do long-term longitudinal–we have this problem with autism. More people today are diagnosed with autism than were 50 years ago. But is that because more people are born autistic, or because we’re better at recognizing what autism is, and earlier?

One of the great things about something like MindMate data is it’s not a diagnosis. It’s a measurement. Let’s pretend we did MindMate for 10 years, you and I, across a large sample of people. I can see, in general, if people’s reaction time is getting better or worse. In general, do they have better or worse memories, and at what point in their lives? Because we’re not relying on a clinical diagnosis. We’re relying on raw data that, in theory, would power a clinical diagnosis. But as you and I know, culture and gender and age and race, all of these things play into how often someone is diagnosed.

GamesBeat: One question some people might ask: If there’s someone with very advanced dementia, a very advanced condition, is it possible to reverse the clock and show improvement that takes them back to an earlier stage?

Wallaert: With the evidence that we have, at least, and the treatments we have right now — turning back the clock, at the moment, is hard. It isn’t something where there’s abundant evidence that we have great treatments. Now, there’s certainly hope. I’m glad people are doing the research. It’s not my research or my interest. For me, right now, I have a plan full of predominantly over-65 folks, in terms of Medicare Advantage. I need to find them solutions for where they are right now, so I lean into things like social support.

Let me put it a different way. There’s one version of the world in which — let’s pretend that mental function, neurocognitive function, can be rated between zero and 100. Zero is bad and 100 is great. When you ask me about turning back the clock — Dean is at 65, can we get him to 65? — that’s one question, and there are great scientists looking into that.

I look at it a different way. Let’s pretend there’s a different scale, which is the quality of life scale, zero to 100. Dean is at a 60. Even if his mental function is declining, if I intervene in the right way his quality of life can go up. If he goes from living alone in a poorly supported system for neurocognitive decline, I can help get him into a situation, an environment, that is going to substantially raise his quality of life. Even if I can’t halt or reverse the decline itself, I can make sure he doesn’t have to have a continual decline in quality of life.

That, to me, is the interesting thing, the thing we can do today. Everyone, everywhere can help make the quality of life for people who are experiencing neurocognitive decline better. We don’t have to wait for drugs and clinical trials. We can do that, all of us together, today. That’s the most interesting thing to me. It’s the dominant aim of my team, the people I work with. Clinical change can take a very long time. Science moves very slow. But we can improve quality of life right now.

GamesBeat: If we take care of this part, maybe that whole immortality thing will work better. If scientists can get us to living a lot longer, it’d be good if they could get our brains to last too.

Wallaert: One of the great tragedies of medicine, I think, is that we’ve made substantial improvements in how long we can keep your physical body in a place where you can have a great quality of life. We need to invest in making sure that your mental quality of life, your brain and your emotions, can match that longevity. Otherwise, I always think about Ray Kurzweil. “I’m going to eat a hundred pills and live forever!” Yeah, but with what quality of life? It’s not just maintaining the ship. It’s maintaining the captain.

Above: Can you play Call of Duty with teens? Are your reaction times good enough?

GamesBeat: There’s a whole other side of this in all the people, especially in Silicon Valley, who are interested in all that brain-sharpening stuff. Taking their loaded caffeine pills, nootropics and all that.

Wallaert: What was the one they were doing where they were dunking each other in super-cold water? They come up with something new every week. There’s a reason I’m not in Silicon Valley. I was a first-generation college kid from rural Oregon. I’ve gotten to do things in my career I never thought I’d get to do. But there’s a reason I’m at Clover. I’m just more interested in how I can make life really good for the average older adult.

I’m a behavioral psychologist, a behavioral scientist, in tech. There’s very few of us. As you can imagine, I get a lot of weird job offers. People like these nootropic companies come and say, “Be our chief science officer!” No. No interest. I’ll be right here doing this.

GamesBeat: I’m getting more tech pitches that have to do with older people. That never used to happen, which is interesting.

Wallaert: It’s an invisible population. Everyone wants to sell stuff to 18-year-olds on their smartphones. People lost track of the fact that there’s a wider America. Parts of the country still don’t have good internet access. Things are built for Silicon Valley, which has gigabit internet. That’s not the reality for a lot of people. In Oregon I had dial-up internet until, I don’t know, 2010 maybe? We need to work around these constraints.

GamesBeat: I just hope this isn’t all because someone’s marketing deck says, “Look how much money we can make from aging baby boomers.”

Wallaert: [laughs] I think it will be for some. I think that’s where business models come in. When I look at job offers, the first thing I look for is, is the business model aligned with the good of your users? If it isn’t, you’re inevitably going to run into trouble. One thing I love about Medicare Advantage is it’s one of those rare places where everything lines up. We only make money if we improve people’s health outcomes. That’s the only way, literally.

By constructing the business model that way — we watch people come into Medicare Advantage and then leave. If they were doing it only because they thought they could work some math and make a bunch of money, those people bow out pretty quick. The only way to make money long term in Medicare Advantage, because of the way the system is set up, is to improve health outcomes. It’s a special place to be.