Amy Hennig has received many kudos over the years for her career making games such as the Legacy of Kain games and the Uncharted series. Those games had memorable characters and stories, even if they were “just video games.”

But she doesn’t view herself as a celebrity in gaming. Instead, she tries to exhibit humility when it comes to talking about her life crafting video games.

After all, not everything has been rosy. Hennig left Naughty Dog in 2014 and went to work at Visceral Games at Electronic Arts. She was in charge of designing a Star Wars themed game with the former Battlefield Hardline game studio. They were making a story-based, linear action-adventure game set in the Star Wars universe.

Above: Chloe meets Elena in Uncharted 2: Among Thieves.

But things didn’t go as planned, and in October 2017, EA decided to kill the project and shut down the Visceral Games studio. As it did so, EA executives said that single-player story-based campaign games are difficult to justify in an era of live operations.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

I caught up with Hennig at the DICE Summit event in Las Vegas. I asked Hennig about that painful experience and she offered her own views on what happened.

As discouraging as that was, Hennig is still bent on making games with complex characters and deep stories. She has started her own independent game studio, and she has been inspired by younger game developers who come up to her at events and say that her games are why they got into the game business.

We had a long conversation about the craft of making the kind of games she enjoys. We touched on why writers embed literary references in games, leaving Easter Eggs for the erudite gamers. Such details show the care that goes into making a game that may take hundreds of people and years of toil to create. I could tell she was still very much invested in the stories and characters she created at Naughty Dog.

And I’m very interested to see where Hennig, who made some of my favorite games of all time, goes next. We had a long talk. But I hope you’ll find it as fascinating as I did. Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Amy Hennig at the DICE Summit in Las Vegas.

GamesBeat: It’s fun to see you become more of a celebrity in the game industry.

Amy Hennig: [laughs] I don’t know why that is. I guess because I rarely poke my head out, so it makes me a strange and unusual creature. A Bigfoot or something.

GamesBeat: I felt like, after Uncharted, the fascination with who wrote the story, who came up with these characters, it got more intense. For you, did you find that there was a pre-celebrity life and a post-celebrity one?

Hennig: I don’t feel like a celebrity, so I guess it’s all pre-celebrity for me. The only time I feel like that is when I come to an event where I’m more recognized. But it’s flattering. I guess there’s less anonymity, where you can just walk around, but it’s not like — in the sphere of celebrities, I’m not a very big one.

It’s mostly nice, because a lot of young people come up to me, game designers, who will say that they got into this because of me. “I didn’t imagine myself having this career, but then I saw you.” That makes everything worth it.

GamesBeat: Is there a Spider-Man thing there for you? Great power and great responsibility? With great celebrity comes great responsibility?

Hennig: [laughs] No. I mean, with great celebrity comes great humility, maybe. When you’re just working away and you have your nose to the grindstone, going through all the trauma of trying to make a game, it’s easy to forget that there are people out there that see it and play it and receive that in a way that’s changing their lives.

It’s hard to imagine, but the fact that people have reached out and said that games help them through a tough time in their life, or they shared it with a terminal parent and played through games together, or it shifted the idea of they want to do with their career because they saw that a certain thing was makable, or that someone like me could make a game — that’s pretty cool.

GamesBeat: It’s good to see the recognition of where quality is.

Hennig: Well, thank you. That means a lot. I’m very touched that there seems to be so much love and affection for the work that I’ve done. When you ask about post-celebrity life, if you call it that, it’s just the fact that people in the industry have been very welcoming. It’s not hard for me to pick up a phone or ask for a meeting and get to talk to folks, be able to talk shop. The biggest difference is access, I guess. It doesn’t make it any less paralyzing to be in the situation, but….

GamesBeat: You get the chance to do bigger things, bigger projects. Get a hold of $100 million or something.

Hennig: That’d be nice. Nobody’s throwing that kind of money at me. People are more likely to trust you, I guess, if they see you’ve delivered before, but all these $100 million bets are scary for everyone. It doesn’t matter what your track record is. Everything’s so volatile. The industry changes so much. It takes so long to make these games, and a lot can change over the course of development.

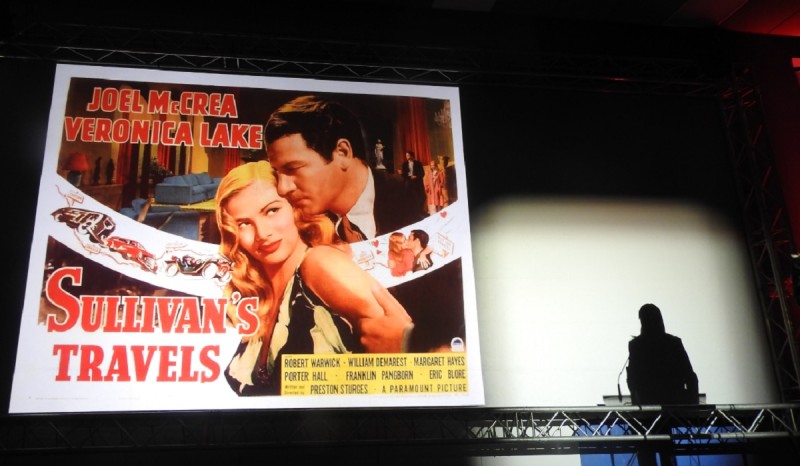

Above: Amy Hennig, talking about Sullivan’s Travels

GamesBeat: When you gave that talk in Montreal about Sullivan’s Travels, [a 1942 film that was referenced in Uncharted and sent a message that escapist fun is OK] I thought that was a nice speech. We were both English majors at Berkeley, right? It felt like something an English major would do, to build references like that into a work of art.

Hennig: We do all these little things that just please us, that nobody’s going to pick up on unless we tell them.

GamesBeat: But to layer some extra meaning into it that people aren’t expecting….

Hennig: Yeah, a few people will pick it up. I put things in ancient Greek — there’s a blackboard in the bar, I think, in Uncharted 2, where I put something in ancient Greek. I did two and a half years of ancient Greek in college. I don’t know why. No point. I just wanted to learn a language that didn’t look like English. I put a little Easter egg to myself there. I don’t know if anyone ever caught it but me.

GamesBeat: It’s funny that all these literary references used to be called other things, but now they’re Easter eggs.

Hennig: Exactly. It was a reference to Homer. Yeah, you need footnotes for these Easter eggs.

GamesBeat: It also seems like it elevates the writing of the story for video games.

Hennig: Having a literary background, you mean?

GamesBeat: Layering in things like that. This is really the story of the Odyssey layered on top of a different, modern tale.

Hennig: Do you find that’s more common these days?

GamesBeat: I don’t think I notice as much of that at all in something like Red Dead.

Hennig: Yeah, more like pop culture references and things. Not Red Dead specifically, but you see more of that kind of layering going on. Not something as nerdy as ancient Greek or T. S. Eliot.

GamesBeat: It can make it feel more special to people, though, make them feel like they’ve discovered something.

Hennig: I think so. Also, sometimes I think maybe it just resonates in a way. If you’re calling back to something that resonated in the past, it resonated for a reason. Maybe it just makes it a little richer somehow. A lot of people have commented on that stuff. Even if they’re not sure where something came from, they can tell it’s a reference. It feels like there’s something to discover if you dig a bit.

That was the basis of all the historical references, the fact that it was based on real history. When we do our exposition dumps about the historical mysteries, that stuff’s all real and true. People can look it up. All the spoken languages, all the written languages are correct. There’s a care that I think we always try to put into the games.

Above: Sully and Nathan Drake in the Uncharted series.

GamesBeat: It seemed like a lot of extra work for something that might go unnoticed in Uncharted.

Hennig: Maybe? But I think the thing is — again, it’s resonating. We always said that we should try to base those stories off kind of grade-school knowledge. Or at least you’ve heard of Marco Polo. You’ve heard of Francis Drake. You may not know anything about them, but you feel like you do. If it starts getting too literate, or too obscure, it doesn’t have the same effect.

What you want is — here’s the historical nugget we all know is true, or we think we do, and then what if? What if there was more to it? If you were going to make up a thing, it feels to me that falls in that sort of mumbo-jumbo problem. Weird on weird. Okay, I have to accept this thing that I don’t know anything about, and you’re going to twist it. Give me something firm to stand on first.

Plus, it’s fun for us, because in the research phase you can grab on to real things. That gives you ideas. You find a picture of a thing and think, “Okay, now we know what the pirate island looks like.” It gives you some foundation to build from as the creator.

GamesBeat: Speaking of weird on weird, at some point in all the Uncharted tales, the supernatural thing comes to life for real.

Hennig: That’s what everyone said about the first Uncharted. The thing is, one of the big inspirations was Doc Savage, which was the precursor to things like Scooby Doo. There’s some mystery, and it seems supernatural, and you have all these clues that you don’t know how to read, but it gives you the whole spooky supernatural vibe of the story. Then, in the denouement, you think, “Oh, there’s an explanation for it.”

We tried to do that. You don’t have quite the same supernatural stuff in, say, Indiana Jones. Or obviously you do with the opening of the Ark of the Covenant, but in terms of mummies and things. With the propulsion at the ends of the stories, all you can do is maybe drop hints that there’s a biological explanation for this. But you don’t have the time to stop and say, “Okay, let’s explain this.” There’s no scene where you pull the rubber mask off the farmer. But that’s where that came from, Doc Savage. That feeling that there’s something eerie and supernatural going on.

GamesBeat: It happens in the Lara Croft reboots as well.

Hennig: That was always a bit more in their DNA. I could see us not including that, but it seemed like it was such a pulp adventure thing, that feeling of something arcane and supernatural behind the scenes. And then giving it the final twist if you can. Maybe it’s a virus? But we never had much time to lean into that stuff. We just had a bunch of slippery naked guys at the end and called it a day.

Above: Jason Della Rocca interviews EA’s Amy Hennig (center) and Jade Raymond.

GamesBeat: Did you ever run into opposition to things like dropping in the literary references? Why do we have to do extra coding for Sullivan’s Travels?

Hennig: No, nobody’s paying enough attention. It’s not extra coding. The boat has to have a name, right? So paint something on there. Victor Sullivan has to have a name, so it may as well be something that resonates for me. There has to be something on the chalkboard at the beach bar. That’s not really the culture of Naughty Dog anyway. It’s not like there’s anybody you’re going to for permission. You just make stuff. If you were trying to do some too-elaborate thing….

GamesBeat: Maybe an artist would say, “I like it better this way, so I’ll change whatever this name is.”

Hennig: I suppose that could happen a few times. “No, there’s a reason for it to be that way.” A lot of that stuff, as the creative director you decide. You don’t have to explain why to everyone. You just say, “This is the name of the boat.” I didn’t tell anyone what the reason was until later.

GamesBeat: A lot of games don’t have that, I think. That’s why I notice it.

Hennig: I think Naughty Dog has always been good at attention to detail and care in all kinds of things. There was the famous newspaper in the bar in Uncharted 3 that actually foreshadowed The Last of Us. Did you find that? Talking about an outbreak. I guess that implies that Nathan Drake and his buddies are all dead. I don’t know. It was just funny. Somebody had to take the time to make that newspaper and put it in the bar. But in the same way, you want to make sure that the cracks in the buildings and all the little environmental storytelling bits make sense. A lot of people pour their love into it. Any time you can put some sort of hidden meaning in, people love that.

Above: Women in Games exhibit speakers at The Strong Museum: (left to right) Megan Gaiser, Bonnie Ross, Jen MacClean, Dona Bailey, Brenda Laurel, Susan Jaekel, Sheri Graner Ray, Victoria Van Voorhis, and Amy Hennig.

GamesBeat: Given the contrast between Tomb Raider and Nathan Drake, did you ever wish that Nathan Drake was a woman?

Hennig: No. It was nothing we could even consider, because Tomb Raider was a thing. We already got criticized for — oh, well, you’re just making Dude Raider. Seriously? Do you know how long of a tradition there is in pulp adventure cinema? She doesn’t get to own the whole thing. So we deliberately chose to have a guy, not a woman, because it would feel like we were invading that territory. She was this aspirational, acrobatic, James Bond character, so we made ours a little hapless, a little clumsy, more like Harrison Ford in Indiana Jones. Right at the limit of his ability a lot of the time. On his heels.

GamesBeat: A creative opposite in some ways?

Hennig: Kind of? That became part of the design. We’re structuring this differently. It’s about companions. She’s sort of a lone wolf. That all changed, obviously. It’s interesting, because there’s almost been a dialogue between the projects. Once they saw what we did with Uncharted — and look, this was also a trend. You look at James Bond, he used to be an aspirational character. Then they rebooted the whole thing, reimagined him with Daniel Craig as being a much more vulnerable character. Not perfect. That’s become more of a trend. Tomb Raider has become a bit more like Uncharted because of that, I think.

GamesBeat: I forget whether you overlapped much with The Last of Us.

Hennig: No, I was there. I was working on Uncharted 3. That was the hard part where we tried to grow the studio and do two projects at once. We had a lot of growing pains trying to make that work.

GamesBeat: What do you remember most now about The Last of Us?

Hennig: I didn’t work on it, since I was working on Uncharted at the same time. What I remember most about all the projects is how we just crunched, and it got worse with every project. It was weird for me because I was always in the midst of it myself. It was odd being on Uncharted and not being on The Last of Us and being able to objectively watch people crunching and seeing the effect it was having.

That cemented some of my desire to — man, if I ever get a chance, if I was ever to have a studio, I’d do it differently. That’s not a criticism of Naughty Dog. I don’t mean it that way. I just mean that — I don’t know. You also just get to an age where you can only — doing that crunch time in the trenches, you start realizing how debilitating it is, physically and emotionally and psychologically and relationship-wise. Just wondering if we could do things differently, do things better.

GamesBeat: Have you ever fully explained why you left Naughty Dog?

Hennig: I don’t really talk about it. I always steer away from things that feel like they could be used for sensationalist clickbait-y kind of stuff. Not that you would do that, but you know how these things go. Fundamentally it’s just creative differences. We had a different idea about which way we should go. That happens.

Above: Amy Hennig left these characters behind. She did not work on Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End.

GamesBeat: Having done that, was it hard to leave these characters behind?

Hennig: Sure, of course. When you live with these characters — they’re coming out of your brain. You’re writing them. They feel like children or something. It’s very hard. I said, ineptly or inarticulatly, at one point — it’s like if you split up with your spouse and they have the kids. You wish them well, but you don’t necessarily want to look at their pictures on Facebook with the new spouse. It was hard for a while, because there was something distant about it for me. I’m not doing it anymore, but it’s continuing, when I lived with it internally for so long.

GamesBeat: I wonder if that’s how George Martin feels about Game of Thrones now that HBO is ending it.

Hennig: Maybe? I would think that it’s hard for any creator that really pours themself into something. You identify with it. To separate from it, I just think that’s normal, for it to take some time.

GamesBeat: It seems like the Tomb Raider reboot was generally a good thing. Fresh eyes took a look at the same thing and decided to go in a different direction.

Hennig: I think so. I’m sure it helped that we blazed a bit of a trail there. Here’s a different way to approach similar material. But also, I think we were all — it’s part of the zeitgeist, like I said. The fact that they took the Bond franchise and rebooted it, envisioning him as a much more flawed, vulnerable, complex character, as opposed to this slightly two-dimensional caricature, this aspirational caricature that James Bond was. We’re not necessarily gravitating toward that kind of entertainment anymore. We want our characters to be complex and flawed and interesting and layered, as opposed to a cartoon.

GamesBeat: I guess that’s a good description of where story-based games have gone.

Hennig: There are still ones that are kind of surface-ey, and that’s fine, because that’s what they’re doing. But in general I think people are getting on board with the idea that when you’re writing characters, you should be thinking about all of their contradictions and flaws and vulnerabilities, not just all of their heroic qualities.

Above: Iden Versio, the Imperial agent you play as in Battlefront II.

GamesBeat: Sort of like how Iden Versio is very different from anyone in the original Star Wars.

Hennig: That’s probably part of it, just the fact that there’s contemporary DNA in it. It’s hard to separate ourselves from the fact that storytelling is different than it used to be. That was one of the challenges of working on Star Wars, in a good way. It was fun to try to figure out how you honor all of the original choices from the ‘70s and the ‘80s, that tone and structure and style, but if you literally did that today it would feel really corny. You have to put a bit of a contemporary twist on it. Reimagine it through a contemporary lens, but still honor all those things that gave it its DNA. Speaking abstractly, but hopefully that makes sense.

GamesBeat: Do you think lots of writers are doing this now in video games?

Hennig: I think so. I think you’re seeing lots of it in TV and film in general. Look at Marvel. Look at how complex those characters are. They could just be two-dimensional superheroes, but they’re all layered and flawed. They have some dark stuff.

GamesBeat: It reminds me of that Jack Ryan show on Amazon. It’s a very different Jack Ryan.

Hennig: Right, because that’s the taste of today. We’re surrounded by that, so that’s also how we write. Writing something that’s simpler and more two-dimensional feels dated.

GamesBeat: The whole “single-player is dead” thing….

Hennig: Speaking of things getting reduced down to memes. I don’t think anybody would say single-player is dead. Look at the current crop of games. It’s just a harder and harder proposition.

Above: John Marston was the hero of Red Dead Redemption, and he is back in Red Dead Redemption 2. Is he a vanishing breed?

GamesBeat: Why is it getting so hard? I don’t know if it’s the eight years to do Red Dead Redemption 2 or….

Hennig: That’s the problem. We used to make games in a year. Jak III we made in a year. Uncharted took three because we had to build the whole engine. Uncharted 2 and 3 both took two years each. That’s unheard of anymore. Three years is short. Right now you can already see, that’s a lot more expensive than it used to be. A lot of games are taking four and five years, sometimes more. Teams are bigger. The fidelity is higher. There is an apparent requirement, whether it’s coming from publishers themselves or players or whatever, that games have more features and are bigger.

I’ve said that I don’t think a game like the first Uncharted, even though it was the foundational footprint for that series, would be a viable pitch today. The idea of a finite eight-ish-hour experience that has no second modes, no online — the only replayability was the fact that you could unlock cheats and stuff like that. No multiplayer, nothing. That doesn’t fly anymore. Now you have to have a lot of hours of gameplay. Eight would never cut it. Usually some sort of online mode. And of course you see where things are pushing, toward live services and battle royale and games as a service.

All of those things — I don’t know the word I’m looking for, but they play less nicely with story. They’re less conducive to traditional storytelling. That has a shape and an arc and a destination, an end. A game that is a live service, that continues, does not.

Above: Arthur Morgan rides his horse in Red Dead Redemption 2.

GamesBeat: I look at the contrast between Battlefield and Call of Duty this year, where Battlefield has single-player and Call of Duty dropped it in favor of battle royale. It was an interesting test, and it seems like Call of Duty won. That’s almost sad in some ways. I wanted that Call of Duty story.

Hennig: When we say single-player is dead — and again, I don’t subscribe to that — I think people are also talking about narrative games. Not just a game that you can play by yourself, because of course there’s plenty of that, but whether narrative is still front and center as one of our key tenets of the title. It’s just harder to do. Yes, you can look at Spider-Man and Red Dead and God of War, and they’re deeply narrative. But they’re also really long. There’s also an understanding that a lot of people may never finish it. They’ll only play the first part of a game.

GamesBeat: 22 percent finished Red Dead.

Hennig: Right. We look at that thing, which seems like it’s leaning hard into story and this character and this world, but with the understanding that less than a quarter of your audience will see the story through. That just makes me crazy, as a storyteller. That’s like saying I’m going to write a book and expect nobody to finish reading it, or make a movie and expect people to walk out halfway through. It’s counterintuitive to wanting to tell a good story and craft it for people.

The length and complexity and the layers that are in these games now, sub-missions and skill trees, all these things are great. I’m not saying we shouldn’t have them. But it makes it harder. It’s harder to tell a single-player, narrative-focused game. That’s why people go to publishers like Annapurna, but it’s at a different tier.

Above: The crazy house in What Remains of Edith Finch.

GamesBeat: Do you think it’s pushing down toward the indies, then?

Hennig: Absolutely. My favorite games that I’ve played are generally indie. Things like Edith Finch and Florence and Return of the Obra Din. Things that, by definition — narrative is front and center. They’re deliberately finite, not very long, and they’re so resonant and memorable.

Versus some of these other experiences that are laudable, these amazing big-budget games, but there’s something — I don’t know. They don’t quite have the same — they’re not as memorable in the way where I read a good book and put it on the shelf. It’s a closed memory. I did that thing. Like watching a great movie. A lot of games these days, it’s very hard to find the time to play them all the way the through, especially if you want to try them all. Who has that time? It’s harder to make the kind of games that used to appear on console in this finite narrative, single-player context.

Above: Though her latest game was a failure, Amy Hennig received an award for her career making great games at Gamelab.

GamesBeat: With something like open worlds and missions, do you feel like that’s a good substitute for some of this? It seems like a way of addressing the demand from gamers for lots and lots of things to do.

Hennig: That’s the thing. It’s not even clear where the demand is coming from, if we’re going to call it that. A lot of times I say this stuff and people say they want to play smaller games, finite story games. Publishers aren’t necessarily funding them or making them. Big publishers, that is. I’m not sure.

I guess obviously there’s analytics and wisdom out there. People want to make sure they’re getting their money’s worth. They want a big long game they can dig into. Maybe they can only afford one game. They want to make sure there’s plenty of content to come back to. Of course there’s also the business side of it. If you keep them in there and keep monetizing, you make more money.

I’m always careful, because I don’t want to denigrate anybody else’s work. That’s not what I intend. There are different kinds of experiences. But part of it comes down, for me, to the semantics of story. A story has an author. There’s intent behind it. It has a deliberate shape. It has an arc, deliberate landmarks, and a deliberate ending. It gets back to the Aristotelian idea of this ending that’s both surprising and inevitable. You can’t accidentally do that through a bunch of random events. You’re not going to achieve that experience. What you’ll get is the equivalent of saying, “This happened, then this happened, then this happened.” That can be satisfying. I just wouldn’t call it a story.

The place for authored experiences that have that intentional shape — t’s not as common as it used to be. Or that experience is so stretched out, much longer than it was originally. I don’t remember how long the first God of War was versus the current God of War.

GamesBeat: The latest is 40 hours or something.

Hennig: And that was unheard-of. We were making games that were eight or nine hours long.

GamesBeat: And you can tell the section of the game where they stretched it out.

Hennig: Exactly. I’ve anecdotally heard — not just about God of War, but about other games as well — even the last Uncharted game, there are places where they say, “Let’s pad that out. Let’s open that up and give them some choice, some alternate missions.” That’s where people check out. The promise of some of these games is propulsion and pace. It’s not just saying, “Give me story in these little nuggets, in an endless stream.”

I find myself as this crotchety old story coot complaining about what, semantically, we mean by story. When people felt like games like Uncharted and The Last of Us were successful, it’s because the shape of the story is so deliberate. I don’t know how you do that systemically or with machine learning or AI, where you’re saying, “Let’s drop a story thing here that will be a downturn or an upturn, or that will feel like an act break.” No.

Again, I always make clear that I’m making a semantic argument. I’m not saying these things shouldn’t exist. But when we talk about players telling their own stories, I get the appeal of that. I just don’t think it’s a story. It’s a series of experiences that are very personal to you, and I get that. But story, by definition, means a beginning, a middle, and an end, deliberately. I love the idea of being able to confidently take players on that journey through these anchor points, but with all this agency between them.

Above: Warren Spector is going back to work on System Shock 3 for OtherSide Entertainment.

GamesBeat: Have you ever thought that you could get to interesting narratives from things that were procedural? Warren Spector’s been arguing that for a long time, that emergent gameplay will result in great stories.

Hennig: Maybe? I’m trying to remember. I don’t want to misrepresent what Warren has said. People have said it’s like Dungeons and Dragons. There’s an ad hoc quality to it. I’m not saying that we can’t have an improvisational quality where players can surprise us. But you still have a dungeon master. There’s still somebody guiding the experience. There’s still probably some sort of a plan, even if we may deviate from it. That person guiding the experience is trying to guide us to an ending that feels artful and meaningful and resonant, not toward “And now we’re done.”

It’s fascinating to think about whether you could say, “We know the principles of story. We can turn it into a system that would deliver meaningful twists and turns.” As an aid to storytelling I think that’s cool. As a replacement for writers I think that’s horrifying. It would feel like a story, but doesn’t a story imply that somebody, with their creative heart, is speaking to you?

GamesBeat: I guess it depends on how good AI gets.

Hennig: I joke about the fact that — it’s like those paintings done by machine learning. They all look like slugs and dog noses. I don’t want to hang that on my wall. I can be impressed that it made a picture, but there’s no soul behind it. I think fundamentally that’s what stories are about. You can feel the soul of the people writing it. If they do it well, you feel like they’re taking you on a journey, lightly bringing you by the hand.

GamesBeat: Do you think you can keep this all going in more of an indie startup company now? Is that where you are?

Hennig: Given the opportunity to start from scratch and not feel like I’m seeking a job at a big publisher or a big developer, I think that — it feels inevitable to me, particularly for those of us in California, that going with a smaller studio model, with external partners and distributed development — you see that a lot in the indie scene. You’ll have a lot of individuals working together to make a thing, and they could be all over, geographically.

That’s going to make a lot more sense. It’s more like the film and TV model, which means of course that unionization becomes even more important. If everyone’s a free agent, an independent contractor, coming together to make a thing, then we need protections.

I think ideally you have a very small production company, your key talent, your key directors and creatives, and then you have really strong partners who share the vision that can wax and wane. In the same way you might work with a VFX house. I think that’s becoming more and more common. You’d have your key design and programming talent inside the business, because so much iteration goes on there, but so much else of what we do can be externalized. With the advent of being able to work through vidcon and screen sharing and all this stuff, you don’t have to be — you can be geographically remote and still feel like you’re in the same room, pretty well. Trying to support a studio of 300 people is just insane.

Above: Do indie games like Celeste represent the future of storytelling?

GamesBeat: You don’t need $100 million for that kind of thing.

Hennig: Here’s the challenge. The stuff I was talking about — can we reach a wider audience that maybe doesn’t consider themselves gamers? They’re more used to the linear space. Can we gently introduce interactive content to them in a way that satisfies or scratches an itch for them? I think one of those hurdles for them might be fidelity. If you do something more in the indie scene, you’re sacrificing some of that trying to chase photorealism. But I think once it looks like a game, or it looks too stylized, or it looks like a kids’ show, you lose people who think it’s not for them.

For me too, I have been chasing this goal of believable characters, nuanced human characters. I don’t really want to abandon that, because I feel like everything is changing so fast that if I stepped away from that to do something stylized, stepping back into that might be difficult. I’m fascinated by that problem. We were working on that a bunch in the Star Wars game. I have some unfulfilled desire to see something like that through. But it’s not cheap, is what I’m getting at. I don’t think that means $100 million, but….

GamesBeat: It’s interesting that there are these movements toward what Epic was calling digital humans. I heard more recently from Edward Saatchi from Fable that they’re doing “virtual beings.” They’re trying to marry AI with animation to make the leap, to make something that feels like a real person.

Hennig: That’s critical. But all of that is still in service to creators, human creators and visionaries and storytellers, to aid them as opposed to replacing them. But yes, I’m fascinated by that. I talk to Kim Libreri at Epic a lot. We share the same goals in virtual production, where we want to get.

GamesBeat: If they can help you do it more inexpensively, that’s a good thing.

Hennig: That would be awesome. But certainly having brilliant technical partners in the space is great too. I’ve been fortunate to have a lot of good connections in the industry that I can draw from for advice, guidance, or potentially partnership, that are some of the best of the best. I would love to be able to do what I’m describing, to have this small nugget of core employees, but then have all of these external partners that may be working at a company like Epic and other external vendors. Pick the best of the best and not feel like your whole business is trying to maintain a large studio.

Above: Epic Games’ Siren demo is an example of digital humans.

GamesBeat: You may need the digital human technology, but you don’t need to have an open world stuck in the middle of your story.

Hennig: Exactly. Again, I can only go by anecdotal feedback, but so many of my gamer friends say, “That’s where I put the game down.”

GamesBeat: That’ll save you $50 million, too.

Hennig: Exactly, there’s that. I don’t think — look, we could argue dogmatically about what a game is or isn’t. I think it’s silly. Our language is reductive. But the whole point of having this crafted journey that you’re taking the player on — this is why I was using Florence as an example. Journey is another example. Edith Finch is a great example.

That’s a very deliberate experience. The way you interact with it means that you feel that experience differently than another person who plays it. The fact that all of your interactions are sort of analog. But the flow of that story, fundamentally, is not going to change that much for everyone. You’re still going to hit these same anchor points. It’s what happens in between them that’s personalized for you, because it’s your own experience. It’s personalized not because you’re flipping binary switches and making choices. It’s because you’re in there exploring the interactive space, the world, in an analog fashion.

An open world doesn’t really fit into that much. I think those games are wonderful, but it’s a different kind of experience. It wants to be more — I don’t know if “curated” is the right word, but a more focused and deliberate kind of thing. It’s more like playing a TV show, to put it in the most crass language, or playing a movie, which is where I started with all of this.

GamesBeat: I thought Joseph Fares’ A Way Out is maybe a good example of the kind of thing you might be talking about.

Hennig: In certain ways. The co-op aspect of it, which was really clever, also probably narrowed its audience in some ways. But yeah. Obviously I think he’s an admirer of Naughty Dog’s games. You can see a lot of the DNA there. But it’s that same thing. If you break down Uncharted chapter by chapter, it’s a lot of handoffs between little cinematic moments and gameplay sequences that are very short. It’s all in the interest of keeping things pumping along, keeping the propulsion of the game and story.

I think Joseph did something similar. There’s a very crafted journey, but the way you go about solving your problems and moving through that world, the pace that you set, defines your experience somewhat.

GamesBeat: Do you have any hindsight yet on your time with EA and Star Wars.

Hennig: Oh, I don’t know. I think I’m still in the middle sight. I guess you’d have to give me a narrower topic than that. Which part of it?

Above: Left to right: Mark Cerny of Cerny Games, Amy Hennig, and Geoff Keighley of The Game Awards.

GamesBeat: Do you think it could have been done in a way that you wanted it and a way they wanted it? I don’t know exactly what happened. Could something have worked out there?

Hennig: I don’t know. I don’t know. There were so many hurdles to overcome in terms of — you have a very expensive studio right in the heart of the bay area. It’s very hard to support compared to studios that cost a third of the price in places where there are tax credits. That’s a hard sell. That was a constant drumbeat, feeling like you had to justify the existence of a Visceral.

Obviously trying to create a third-person cinematic traversal action game with an engine that was made to make first-person shooters, that was a hurdle. But we knew going in that that was the goal. We were going to put this functionality into Frostbite. A lot of the team was hired to do Battlefield, and so that was a bit of a cultural shift, to make this different kind of game. Normally you cache for the project you’re making rather than trying to — it’s hard to convert the people you have if that’s not their type of game.

We were very far into development. We had a lot of material. I just think that there was a shift that started feeling inevitable. EA is just not — they hired me for a reason. They know what I do. But I think that where EA is at right now, they’re looking more at games as a service, the live service model. More open world stuff, trying to crack that nut, versus this more finite crafted experience.

We were trying to make sure that we built in other modes and extensibility and all that stuff. But the fundamental spine of the thing was more like Uncharted than one of these open world, live service games. That’s a big gap to cross. I don’t know how you get from here to there. And then to try to push something that may not quite fit into the portfolio as it is today, and try to do it at this really expensive studio — it was a bit of an uphill battle. All of that stuff is publicly known.

I’m not going to pick over the bones of the thing or tell tales out of school, that kind of thing. I don’t not understand the decision. It was something we were struggling with the whole time. Does this make sense? Is this something EA really wants to do? I certainly regret the fact that there’s a lot of good game there that I would love to see the light of day. A lot of people would. One never knows what might happen.

GamesBeat: Anthem seems like the opposite, it sounds like.

Hennig: In a lot of ways. It’s more social and open. Everybody’s trying to crack that nut. That’s what I’m saying. Some of this is very personal resolutions or conclusions for me. I want to make sure that I’m still be objective enough that I’m not just imposing my own personal conclusions on the industry. But I feel like the experience I just went through is more symptomatic than isolated. It’s very hard to make this kind of content in a world and an industry that’s trying to crack this other nut, the live service model. How do we have a big game that’s ongoing and monetizable? I’m not trying to put a nasty spin on that word. It’s just a reality.

Then you try to sell this finite, crafted thing. What does that get sidecarred onto so it can exist? I don’t know. Or do you just go into a different area where that content makes more sense? That’s why I was exploring VR. Can you do a deliberate, crafted story in that space, more so than you can in the triple-A console space right now?

Again, when I say “finite,” I still feel like even these big games — single-player is not dead. Look at what’s nominated. But they still bear the burden of being bigger and deeper. We’re still raising the ante all the time. Seeing these games, people are working harder and crunching more. Development is longer and riskier. What if any of these things didn’t hit? If there was nothing there after five years? That would tank a studio. These are massive, terrifying bets.

GamesBeat: The good thing seems to be, maybe, that for every company that adopts a certain strategy and goes off in that direction, another company might see an opportunity to go in the other one. Maybe the platform holders will go that way.

Hennig: That’s the hope. When people point at Sony’s games — I mean, God bless Sony for their dedication to this kind of content, even though it is growing and getting more and more unsupportable. I don’t think anyone would argue that. It’s a different proposition than it was 12 years ago.

What you have to understand is that Sony is selling hardware. If you’re a platform holder that has an incentive beyond selling that one piece of software, then yeah, they’re more likely to invest in stuff that’s going to be exclusive to their platform. Initially, you have to seek out those kinds of partnerships. Do you want content like this on your platform? Do you want to help fund it?

GamesBeat: It would be nice if you could bring all the resources you need, but still be independent. From your last job, do you think you’ve seen that independence is important? Being able to make the call.

Hennig: That’s one of the benefits that Naughty Dog has. They’ve managed to maintain a culture of — even despite their size now, this radical risk-taking which enables greatness. It’s also a tightrope walk. You embrace that and accept that you’re in the business of risk. But a lot of big publishers aren’t going to necessarily have the same mindset. As an individual, or starting a small studio, you can choose to say, “That’s our culture. We embrace risk and the unknown. We have to take chances. We have to be wise and figure out when we have to hold back.” You have to find partners that feel the same way, rather than trying to fit yourself into a box that doesn’t work.

Above: Dr. Grordbort’s Invaders

GamesBeat: I’ve heard some crazy things, like Greg Broadmore’s talk about Dr. Grordbort’s Invaders.

Hennig: I really wanted to see that!

GamesBeat: Working for seven years on a Magic Leap game.

Hennig: I know, I know. Again, if you have a platform and somebody says, “We want content. We need people who are pushing the envelope in our medium, with our technology,” that’s an exciting place to be. The scary part is you might make something that never comes out, or doesn’t get seen by many people. But that’s certainly one funding model, to find people that need content and get them to partner.

That’s why I said that it might just be getting more like what we see in Hollywood. It’s not about what company you’re joining and making content exclusively for them. It’s all of us moving around as free agents and finding partnerships that make sense, people that are looking for a certain kind of content.

GamesBeat: I’d hope that backers would see the wisdom of putting their money into something you’re making.

Hennig: Me too. I’ve had lots of good conversations. It’s not like I’m out there completely hat in hand. I’m just having conversations to see what everyone’s saying. I’m getting antsy to get back to really making something, beyond just conceptually. And of course, you have this cart and horse, chicken and egg problem. I’d love to start hiring a staff around me to start exploring some stuff, but I can’t do that out-of-pocket. I’d be broke in no time. Especially in the bay area, going back to that topic. It really does come down to finding partners that want to start doing exploratory funding, just seeing where that takes us.