As tempting as it is to bombastically describe the current state of augmented reality as a “disaster,” my personal view is more nuanced: AR is almost through its slow and highly public struggle through infancy. Developers are trying to evolve past impractical early hardware and primitive software, while consumers are waiting for an Apple-class polished consumer solution to define the market.

The timeline for that product is apparently “next year,” as the latest Apple AR report says the company has decided to release AR glasses that require an iPhone for most of their processing. Whether you see that as a great relief or a harsh slap in the face depends on how excited you’ve been about Leap Motion’s, Microsoft’s, and Magic Leap’s separate AR initiatives. There’s now very little chance that Apple’s glasses will require a wall-powered computer, a housing the size of snow goggles, or a belt-mounted computer puck — all options others have promoted.

That’s good news, at least for now. Assuming today’s report is correct, Apple has determined that it can’t yet stuff a decent computer into a headset, and isn’t going to sell you a separate computer just to tote around for AR. If a separate processing and networking device is needed, it should be the one you already carry everywhere — your phone.

Qualcomm already reached the same conclusion. Last month, it went public with a new XR Viewer initiative that will let Android 5G smartphones connect to lightweight AR headsets with displays and hand-tracking cameras inside. Multiple companies are already working on both phones and headsets with XR Viewer support, and the earliest models will likely hit the market before Apple’s.

Above: Microsoft’s Alex Kipman with the new HoloLens 2.

As of early 2019, alternatives to phone-based processing haven’t proved practical for consumer AR. Microsoft is perhaps the most successful maker of fully head-mounted computers, but even after years of working on AR wearables, its just-announced HoloLens 2 seemingly couldn’t get smaller than a decidedly “industrial” size.

Granted, Microsoft isn’t great at miniaturizing new technologies — it focused on table-sized Surface devices when Apple was building its first pocket-sized iPhones. But even under pressure to make a more consumer-ready AR device than the low-selling HoloLens 1, and with access to smaller, faster, and cheaper chips, it instead opted to stick to the lower-volume enterprise market.

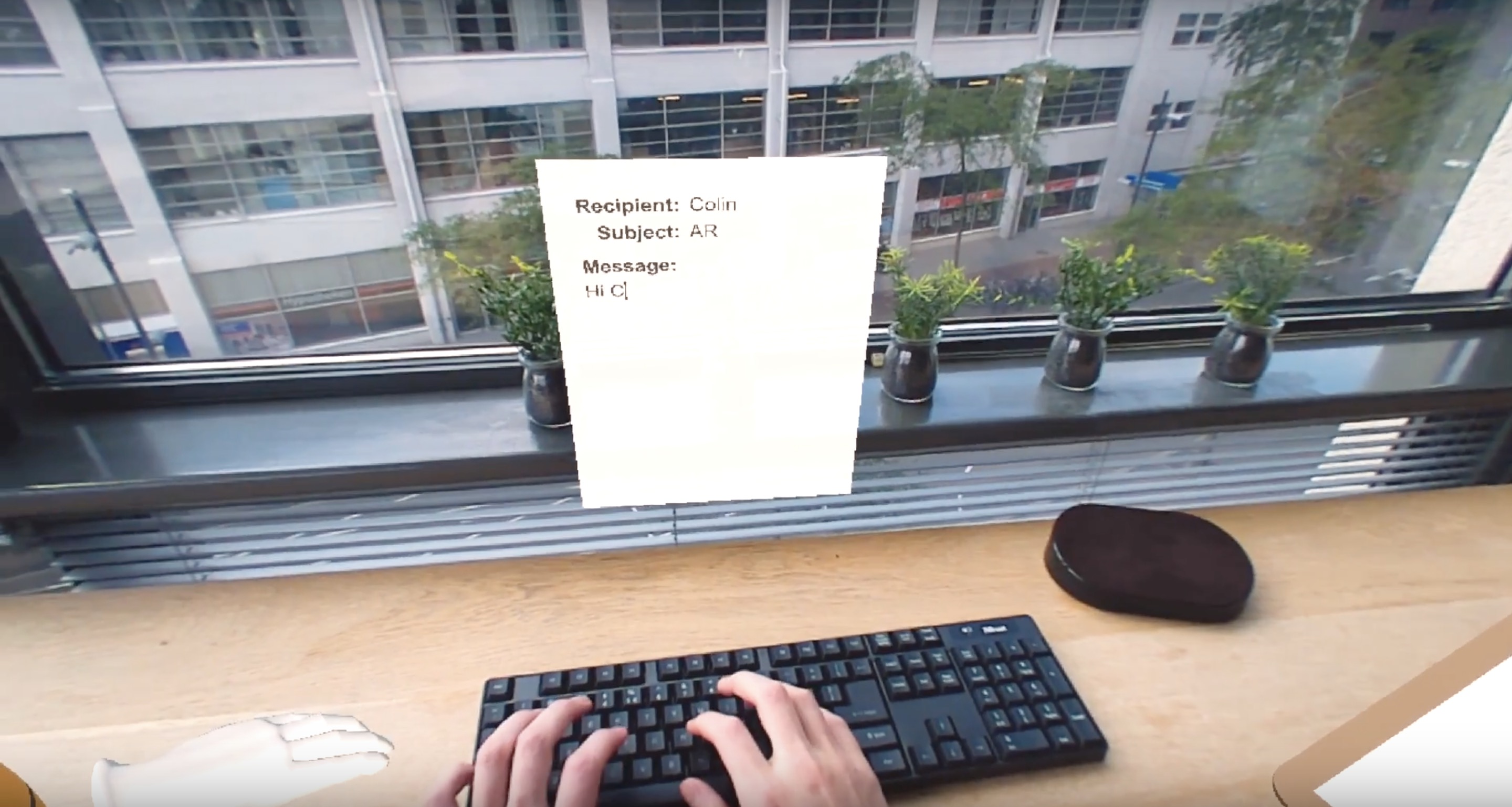

Wall-tethered and semi-portable AR devices haven’t fared much better. Leap Motion’s AR hardware is still strictly for DIY tinkerers, and though the Greenhouse Group showed an interesting demo last year of how AR could be used to let office workers conjure up workspaces wherever they found hand-tracking stations or keyboards, I don’t think average consumers will embrace AR hardware that’s stuck indoors.

Magic Leap’s alternative, Magic Leap One, is “semi-portable” in the sense that you can walk around with it, but you can’t use it outside since it currently depends upon a Wi-Fi connection for data. You need to wear its included computing unit on your belt or a body strap — a limitation that doesn’t seem likely to change when the company moves past its current developer version to a second- or third-generation version with 5G cellular connectivity, though it will at that point be able to work at least somewhat outdoors.

Above: Magic Leap One relies upon a body-worn computer for its processing.

Apple was reportedly exploring a separate wall-tethered or portable computer for its AR headset, running a new operating system called rOS (“reality operating system”). But it may have just been prototyping the hardware that would eventually shrink inside a headset using future advances in chipmaking technology.

Especially after today’s report, I believe that rOS was, like the Apple Watch’s watchOS, designed as a scalable subset of iOS that could evolve with additional features as the AR hardware becomes more powerful. Just like watchOS, it can be subservient to iOS for as long as that’s necessary, then go solo at some point in the future.

Relying on an iPhone for processing, networking, and location services has another key benefit: pricing. Apple isn’t averse to finding ways to sell a customer three substantially overlapping devices (say, iPhone, iPad, and Mac) when two or even one might do, but as weak sales of HoloLens and other AR headsets have demonstrated, average people aren’t willing to pony up $1,000 or more for wearable computers.

A decade may pass before that changes — even today’s most popular wearable computer, the Apple Watch, appears to sell mostly at $400 to $700 price points. It’s worth noting that neither Apple Watch adoption nor CPU performance is yet at the stage where Watch could serve as a wireless computer for AR glasses, though I strongly suspect Apple is exploring that option, as well.

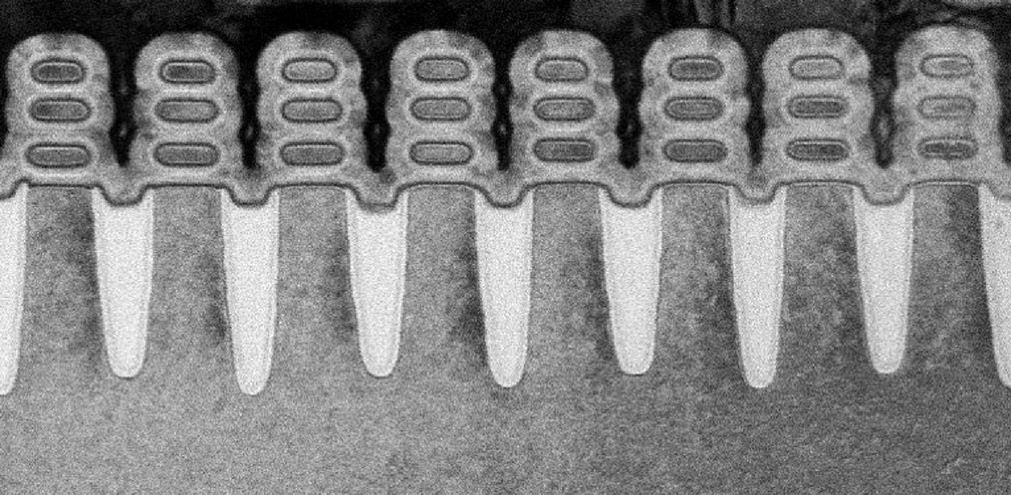

Above: A close-up of IBM’s 5-nanometer transistors. The circuits are 5 billionths of a meter apart.

As of today, it appears that Apple and others are three or fewer years away from being able to fit their entire computing solutions inside glasses frames. Within that timeframe, chipmakers are scheduled to move from the current bleeding-edge 7-nanometer manufacturing process down to a 3-nanometer process. That will let companies like Apple produce chips as powerful as today’s at less than one-fourth the size. Some of today’s pocketable technologies will become wearable, and some of today’s wearable technologies will become nearly invisible.

When that happens, you won’t need to carry a phone at all times with your AR glasses, just as you no longer need to carry an iPhone if you have a cellular Apple Watch. That step took Apple three Watch generations to bring to market, but thanks to continued improvements in chip manufacturing technology and engineering, it didn’t take anywhere near as long as it could have.

I’m optimistic that AR glasses will be aided by the same steady march of technological progress. In the foreseeable future, AR glasses will have moved past the baby steps of their infancy to literal walking, running, and driving applications, and by the time we reach 2030, we might not even remember what life was like before them.