testsetset

As cities look for new ways to combat congestion and toxic fumes, technology is playing an increasingly big part in the problem-solving, be it through using ride-share data to spot traffic patterns or tapping Google Street View cars to map air pollution in neighborhoods.

Waze, the crowdsourced navigation app that Google procured for more than $1 billion back in 2013, has been ramping up its public partnerships over the past five years through its Connected Citizens Program (CCP). From Waze’s perspective, the two-way data-sharing pacts are all about improving its navigation app, while municipalities and other organizations can improve their own infrastructure projects via Waze’s traffic data.

You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours, is the general idea here.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Waze has a long-standing partnership with Transport for London (TfL), for example, the local body responsible for the entire public transport system in the U.K. capital. Next week, the duo will activate the next step in their integrations, as London looks to help drivers navigate some potentially sticky — and expensive — new regulations that are designed to cut pollution in the city.

Breathe easy

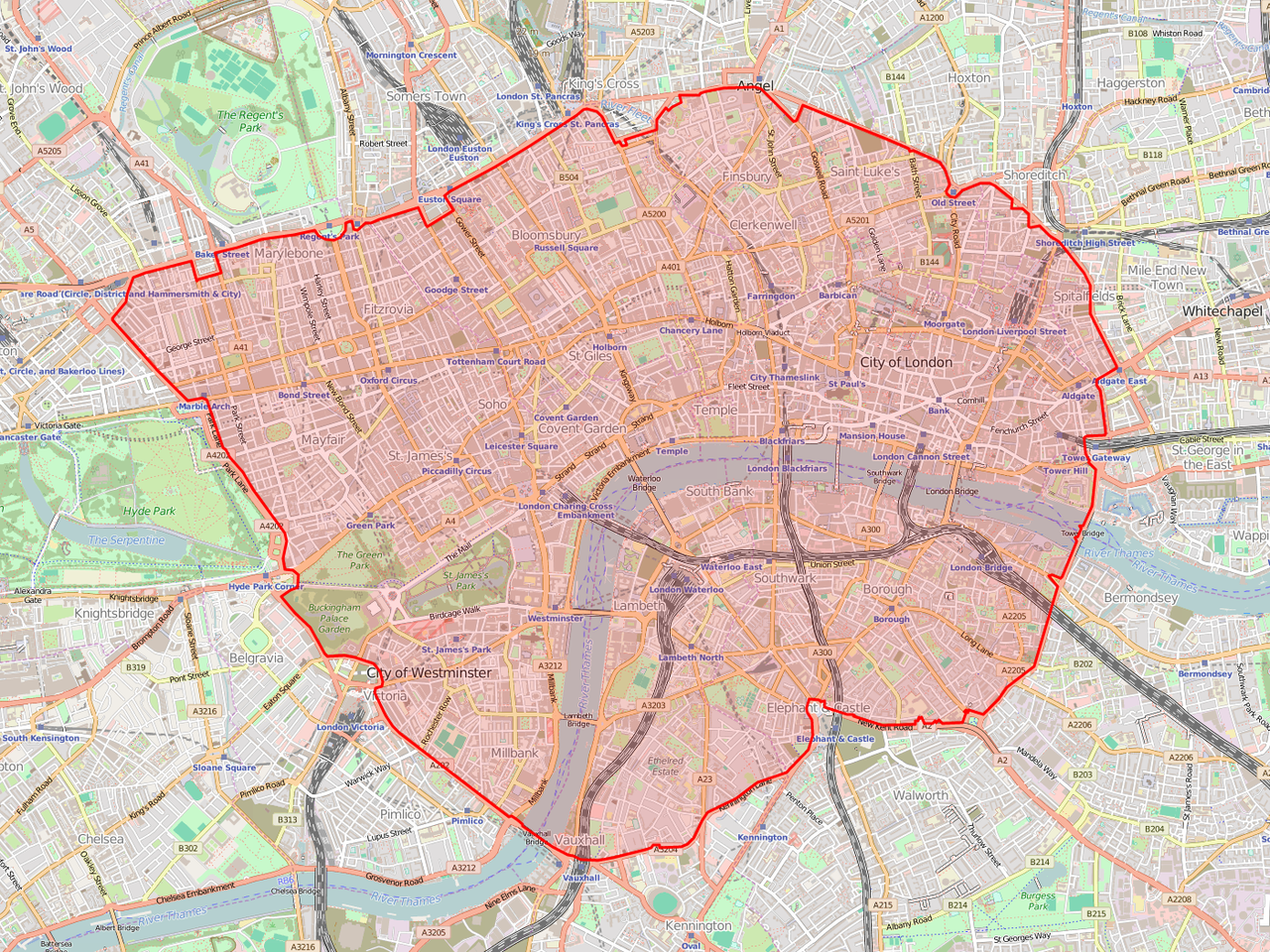

The problem? Nearly 8 million Londoners — or 95 percent of the city’s population — live in areas that exceed the World Health Organization’s (WHO) pollution target by at least 50%. Thus on April 8 — this coming Monday — London’s new Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) will come into effect starting with central London, with plans to expand the zone to include the capital’s suburbs by 2021.

Though other cities have implemented similar levies and restrictions to reduce harmful emissions, including Paris, Rome, Amsterdam, and Antwerp, some have called London’s ULEZ one of the most radical anti-pollution policies in the world.

That may be an overstatement, but ULEZ will undoubtedly be a big step-change for travelers in London.

The ULEZ scheme runs 24/7 in midnight-to-midnight cycles. This means that if your visit into the ULEZ boundary spans two individual days, you will have to pay the £12.50 ($16) charge twice. By way of example, if you briefly dip into the zone at 11:59 p.m. on a Tuesday evening, and promptly leave two minutes later at 00:01, you will pay twice. And then there is the existing £11.50 ($15) congestion zone charge, which is in operation each weekday from 7 a.m. until 6 p.m., to contend with.

Above: London’s new ULEZ zone will be the same as the congestion charge zone for the first two years.

If, for example, you enter the ULEZ (which will cover the exact same area as the congestion zone for the first two years) during a weekday, and you don’t have a car that meets the minimum emission standards, you will have to pay around $30 for both the congestion and ULEZ charge. Bear in mind that does not include parking fees, and it assumes that you do not stay in the zone after midnight.

Moreover, if you inadvertently stray into the ULEZ without realizing it and don’t proactively pay the charge, that soon turns into a £80 ($105) fine — £160 ($210) if it’s not paid within two weeks.

Put simply, driving in London is about to get a lot more expensive for those with older petrol (pre-2006) and diesel (pre-2015) vehicles.

Smart routing

Although cites around the world are engaging in plenty of activities designed to encourage people to ditch their cars, the fact of the matter is people like the personal freedom afforded by having their own private transport — and that is why Waze is expanding its partnership with TfL to serve as the exclusive provider of so-called ULEZ “smart routing.”

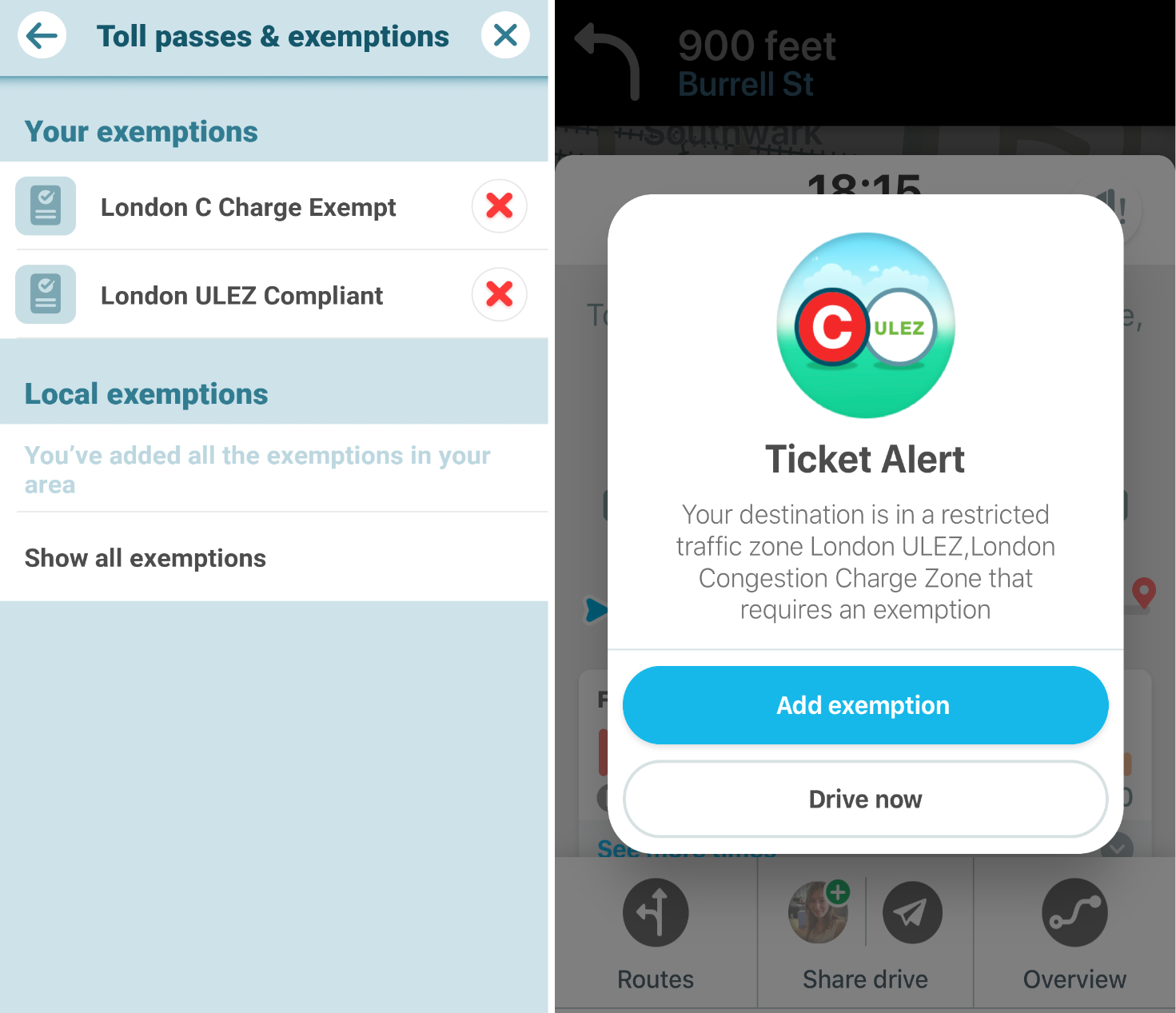

This means that drivers can now indicate within the Waze app whether their vehicle is ULEZ compliant — if it isn’t, then they will receive an alert and can decide whether to travel through the ULEZ area.

“We can’t physically take cars off the roads, but the route to cleaner air could start with one notification at a time,” noted Waze’s U.K. country manager Finlay Clark.

Above: Waze with ULEZ integration

For Waze, this integration is one more reason for drivers in the city to use the navigation app — it will help them steer clear of fees and fines. But the city’s gain here is also worth highlighting, as the two-way data-sharing means that it can see how many drivers are rerouting or changing their journeys to avoid ULEZ — it’s all about measuring efficacy and being able to justify its decision to introduce ULEZ.

In six or 12 months time, TfL — a publicly funded body — can reveal, perhaps, that 15% of drivers are now choosing to stay out of central London, where pollution is at its worst.

“London is now the sixth most congested city in the world and by supporting ULEZ, we’re playing a big part in removing congestion, which should ultimately help improve air quality,” Clark added. “The ULEZ-supported routing will not only help to decrease harmful emissions, but also help drivers to avoid unnecessary fines and toll charges.”

The partnership builds on similar existing integrations Waze has initiated through CCP elsewhere, including pollution-thwarting initiatives in France (Crit’Air), Italy (ZTL), and Belgium (LEZ) that help “redistribute drivers” by keeping them out of restricted zones.

As CCP enters its fifth year in operation, VentureBeat caught up with Avichai Bakst, Waze’s European head of partnerships and CCP, to get the lowdown on how it has been striking deals to help fuel and scale its platform with data.

Natural cause

The genesis of Waze’s CCP initiative can be dated back to before its official launch. In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, a devastating storm that battered North America in 2012, the Federal Emergency National Agency (FEMA), along with the White House, enlisted Waze to show where all the available gas stations were that hadn’t been affected by the hurricane.

“Nowadays, we give solutions on urban infrastructure and governmental projects, that are happening in the city, as well as natural disasters,” Bakst said. “And that was one of them. Not only did we benefit from the spike of users, which wasn’t what we were looking for, but we [could] communicate such impactful data back to the users.”

The CCP officially launched in 2014 with 10 partners, spanning the U.S., Brazil, Spain, Indonesia, and Costa Rica — specific partners included the New York Police Department, Los Angeles County, the states of Florida and Utah, and the city of Boston.

Some of these partnerships actually preceded CCP. A year before its launch, the office of Rio de Janeiro’s mayor Eduardo Paes contacted Waze to enquire about how it could monitor its road conditions in the build-up to a visit by Pope Francis. The Centro de Operacoes Rio (COR) then embedded the Waze API into its traffic control center so it could add crowdsourced driver reports to complement data from its existing sensors and street cameras.

“Road sensors and cameras are cost-prohibitive and can’t scale to every corner of our city,” noted COR CEO Pedro Junqueira at the time. “The context of why traffic has occurred, in addition to specific incident reports, is invaluable.”

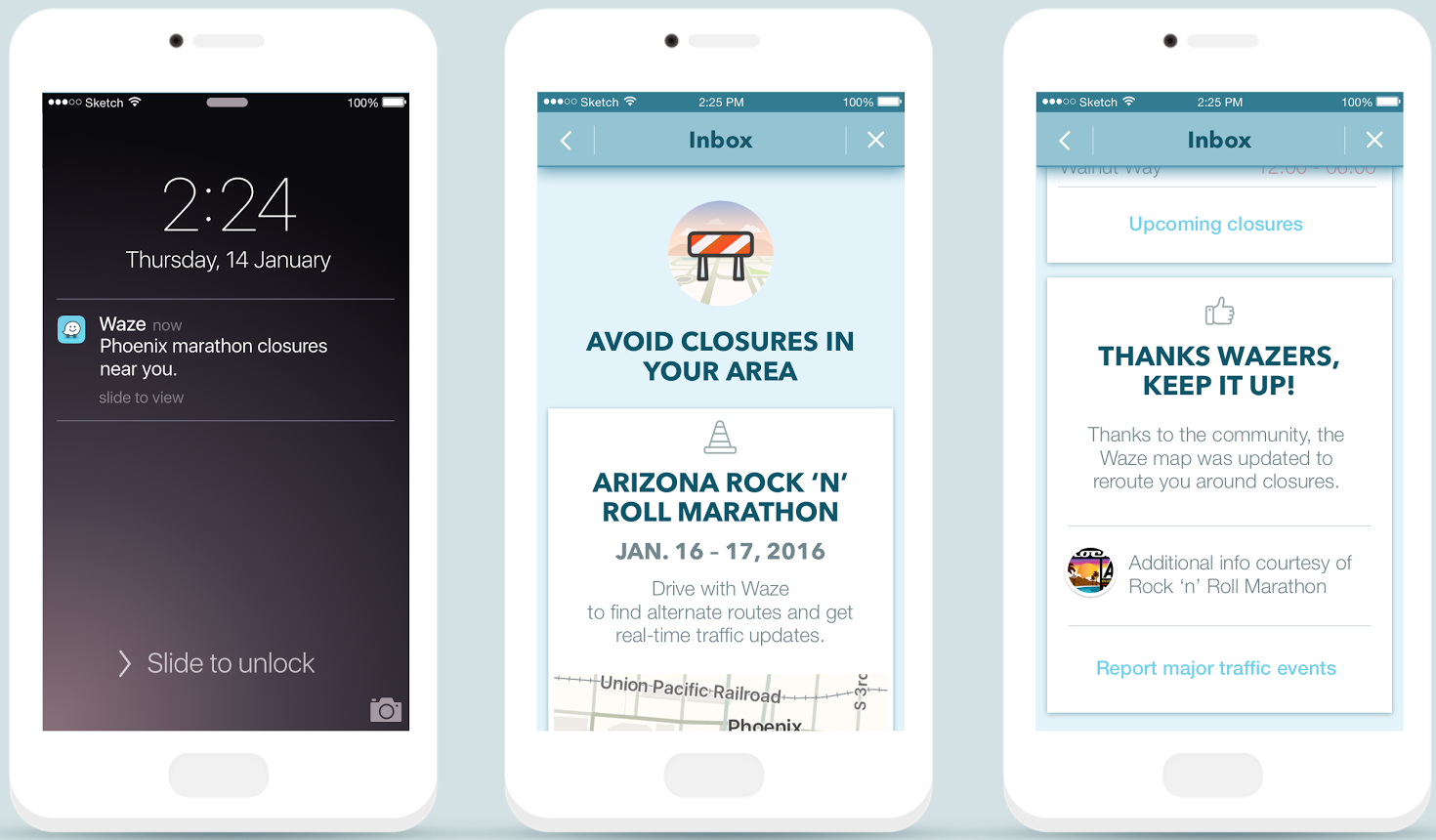

Waze gleans data from myriad external sources, including event organizers, to help avert traffic congestion through improved two-way communications around major events. This means anyone from marathon organizers to sports stadium operators can inform Waze about planned road closures, while in return event organizers can help to avoid further congestion from unsuspecting travelers.

Above: Waze Event Warnings

Waze has also struck partnerships with other private bodies, such as traffic management platform Waycare, which pools multiple data sources, including connected car platforms, telematics, road cameras, construction projects, and public transit, to establish a more accurate picture of a city’s roads and help municipalities improve infrastructure.

Such data not only helps Waze with its own navigation app, but it also enhances its proposition to public bodies as part of CCP.

Transport for London is one of Waze’s veteran partners, which implements Waze data in its control room, but Waze now counts hundreds of similar partnerships, all with a similar goal. “We have many partners that do that — they use the data of incidents, whether that is potholes, or traffic lights that don’t work, or just boring congestion,” Bakst said.

Feeding into CCP is a number of related programs that, while technically separate from CCP, are all in the “same neighborhood,” as Bakst puts it, and serve the same overarching purpose: to help cities reduce emissions and improve traffic flow.

Beacons

Above: Waze Beacon

Waze launched its beacons program back in 2016, serving as a Bluetooth-powered alternative to circumvent GPS blackspots in tunnels.

Waze beacons transmit a wireless signal that can be picked up by any phone or tablet with Bluetooth enabled, and ensures drivers can still navigate deep underneath the city’s thoroughfares.

“If you head into a tunnel that’s a few miles long, that could be 15-20 minutes and you lose connectivity — which is very annoying,” Bakst said. “You might lose your exit, you might not understand where you’re heading, what the ETA is, and so on.”

The beacons are offered not only to its CCP partners, but municipalities and other private tollway and road organizations. Through its partner Bluvision, Waze provides cities with physical Waze-branded beacons, which cost $28.50 per unit. Roughly 42 devices are required for each mile of tunnel, meaning that cities will pay a little more than $1,000 (plus labor) for every mile they want covered. And Waze is very careful to point out that it makes no money from the sale of these devices — it only really cares about the data.

The purpose of the beacons is twofold: It ensures that drivers don’t get lost in tunnels, and that Waze (and cities) don’t lose data due to blackspots.

“Most of the tunnels in New York are all powered by Waze beacons, and Chicago has many partnerships with Waze as well,” said Bakst. “And then we have partnerships with airports or governments or municipalities, regardless of the CCP agreement that we might have with them.”

Waze Carpool

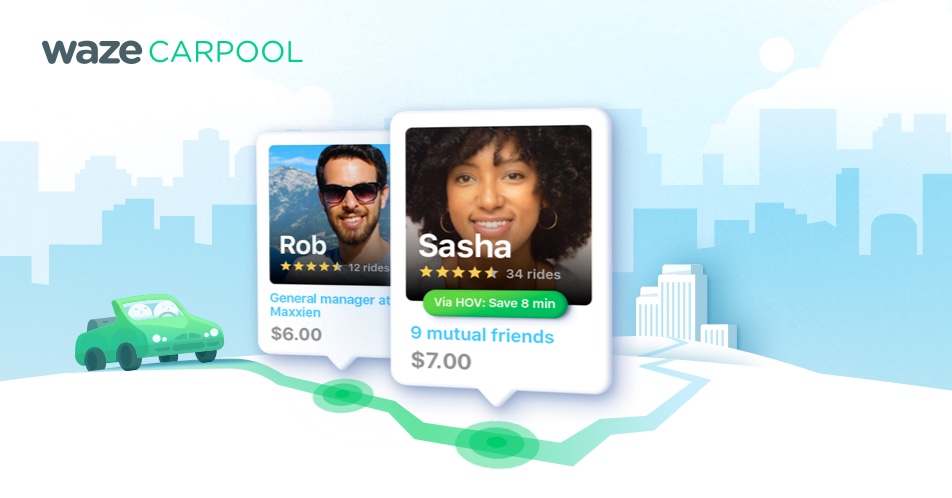

Waze first dabbled with carpooling in its native Israel way back in 2015, when it launched a small-scale service called RideWith. Two years later, the company expanded its ride-share service to Brazil, before rolling it out to the U.S. back in October.

Similar to Beacons, Waze Carpool isn’t really a core element of CCP, but it’s part of the same idea — it’s all about helping cities manage traffic and, ultimately, get as many cars off the roads as possible.

“We’re heading to a future where less and less people are driving cars,” Bakst said. “CCP is all about planning cities for the next day for the next year or for five years from now. Municipalities and governments also nowadays understand how carpool is so needed in their areas.”

There are, of course, countless alternatives out there, and in many regards, Waze is late to the game. In the U.S., Lyft recently became a public company, and Uber is preparing to do this same.

So isn’t Waze up against it from the get-go? Taking the diplomatic approach, Bakst said that Waze doesn’t see the incumbents as competition — they’re all part of the same push to change the public’s mindset away from “driving alone” to sharing cars and removing vehicles from roads.

“The competition is the mindset of us humans that still want to drive alone, and don’t understand how by doing that, how negative the impact is,” he said. “So if you asked me who our competitors are, those are the drivers that drive alone, which, really, is all of us.”

However, there is one key differentiator for Waze’s carpool service: It doesn’t make any money from it. In fact, it encourages participation through covering some of the costs that would normally be paid by the riders.

“Currently we’re sponsoring it, because we want to shift it faster,” Bakst said. “And we want that mindset to kick in fast.”

Whether that will always be its model isn’t clear, though at some point it would of course make sense for Waze to shift all of the costs to the rider so that it’s at least not losing money on it.

“I’m not sure where that is going, to be honest,” Bakst said. “Currently, [by covering riders’ costs] it’s encouraging people to take carpool. That’s why we’re subsidizing this right now. If in the future, there will be a business model, I do not know. I think it will take a very long time until we figure that out.”

Data as currency

It’s interesting to see how Waze has evolved from a crowdsourced navigation app based out of Israel into a core component of cities’ infrastructure projects globally. And looking at its various programs, it’s clear how Waze has managed to scale its platform: It has focused less on selling its data and more on making it accessible. Its data is effectively used as a mode of currency.

At its core, Waze’s CCP is all about data-sharing — no direct financial transactions are involved; the beacon scheme is designed to be as affordable as possible for cities to get on board with. Waze doesn’t take a cut of hardware sales, and it actually works with other navigation apps too; and then there is carpool, which Waze is not only not making money on, but is actively subsidizing.

Waze does make money from other initiatives, of course, including advertising — the Waze app serves contextual ads for gas stations, coffee shops, and places that drivers could be interested in on their journey.

But as a case study in how technology companies can leverage their data to grow and garner goodwill, Waze is a great example. And it’s not alone.

Uber launched its Movement platform back in 2017, pitched as a way for urban planners to make more “informed decisions” about cities using Uber’s gargantuan arsenal of data. That it no doubt does. But with a track record of riling cities across the globe with aggressive tactics, the move was also about currying favor with local authorities.

By way of example, Uber originally lost its license to operate in London back in 2017, and as it appealed this decision, Uber launched its Movement platform in the U.K. capital last May. A month later, Uber won back a probationary 15-month license.

Uber Movement alone likely didn’t turn the tide in its favor, but it was certainly part of its strategy to win friends — and it further highlights how data is a valuable currency.

As for Waze, its immediate future is about ensuring that its app has access to as much data as possible, which benefits it, its parent company, and the cities it works with.

“We surpassed 900 partners globally,” Bakst said. “That’s the amount of partners we have — and they all belong to this [CCP] program. And that is all about a free, two-way data exchange.”