Sam Barlow’s Telling Lies gives you the feeling that you’re searching through an enormous trove of surveillance data scooped up by the National Security Agency.

A woman has stolen the data and has about four hours to pore through the material to solve a mystery. And Barlow, the creator of the interactive movie game Her Story that won numerous awards in 2015, says there are 96 lies and one big truth to uncover.

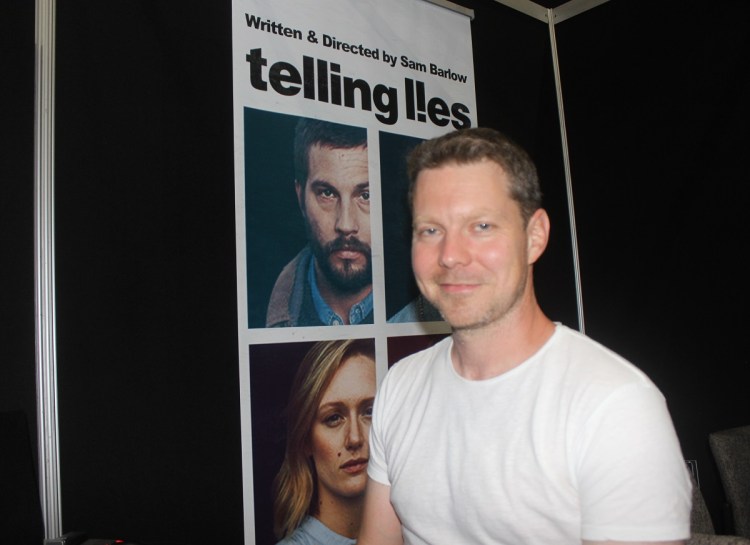

Barlow demoed Telling Lies, which will be published by Annapurna Interactive, for me at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), the big game trade show in Los Angeles. This game’s video scenes include actors Logan Marshall-Green (Prometheus), Alexandra Shipp (X-Men: Apocalypse), Kerry Bishé (The Romanoffs), and Angela Sarafyan (Westworld).

As with Her Story, the game mechanic is searching through a trove of video. If you hear a character say the word “love,” you can search for that word in the videos and the engine will surface all of the scenes where a character mentions it. Then you can watch those videos and uncover more of the story.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Each video shows a character speaking intimately to someone else. You have to figure out who that someone else is or what happened to trigger the private video call in the first place. The linear story of the video is torn apart and fragmented. When you patch it all together again, you’ll be able to see an intricate web of relationships between the characters.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Telling Lies has 96 small lies.

Sam Barlow: I’ll just show you a little bit so you can see how this thing plays. This is the very start of the game. You see this woman arrive at her Brooklyn apartment late at night, in a hurry. She rushes in. I’m doing my level best to be the anti-Kojima and get you into the game quick. [laughs] Making sure the cinematic is less than a minute long. We do a little Contact moment. You remember the movie Contact, with Jodie Foster? The bit at the start where she runs into the screen and you realize you’ve been looking in a mirror. [Editor: You can see the character’s reflection on the screen].

We drop in and she logs in to her laptop. She has this stolen hard drive. She sticks it in, boots up to this NSA database, and now we’re in control. Very similar to Her Story, you’re just dropped in and you can feel free. She’s started by typing in the word “love,” which is somewhat evocative and interesting in itself. If you want you can look around the hard drive a bit, look through some of these documents, and understand the tone of the world you’re in. This is a government database that’s been stolen.

GamesBeat: How do you communicate that to people? Do they already know, or is there somewhere they discover this is government information?

Barlow: There are a few bits and pieces if you choose to read them, files and things that give you a sense. This is the NSA field manual as to how to use this piece of software. If you choose to, you can explore this and figure some of that out. When you start searching, you can pick up on the conceit that what we’re seeing is secretly recorded conversations between people over the internet. Most of the content you find is two people talking to each other.

One of the restrictions or constraints that makes this interesting is, when these are captured and ripped off the internet, both sides are captured separately. If two people are talking and I drop in — if I search for the word “love,” it drops me in at the point where she says that. This is a four-minute conversation and I’m dropped in at minute three. You instantly have the question of, what’s happening? Where am I? Who is this? Who are they talking to? There are lots of layers. We want to engage your imagination, have you infer things, pick up on subtext, put together the context, and figure things out.

Above: Angela Sarafyan is one of the stars of Telling Lies.

GamesBeat: Is your first move here to go back to zero and watch the whole thing?

Barlow: This was part of giving you more tactile connection to this, giving you more verbs to interact with these videos. We have this very analog scrubbing mechanic. You can scrub through the videos, rewind through a scene, and one of the fun things here is, you might get dropped into a scene and it’s the end of an argument. Someone’s crying. How did they get here? Then you start scrubbing backwards. You’re still picking up the subtitles as they go past, so you watch the scene in reverse. We get to play with lots of different interesting non-linear temporal things.

What we do as well, if you see something interesting, you can just click it and jump straight into a search. If you’re picking up little rhetorical devices, or understanding that there’s a question and answer going on, it’s easier to ping between different sides of the conversation or chase down a thread. If you see a name that sounds interesting, you can click here and jump to that.

One of the things that surprised me with Her Story was the extent to which people 100-percented that game, exhausted it. If that was fun for them, great. But I didn’t want people to feel that FOMO, like they were obliged to do that. In this game I wanted to encourage people to lose themselves in it. There’s so much more content.

GamesBeat: Does this take a lot of computing power or disk space?

Barlow: There’s a reasonable amount of disk space used. That’s one of the challenges we had, especially on mobile. There’s four to five times as much stuff as we had in Her Story. I wanted people to just — I keep making the comparison to something like Breath of the Wild, a game that felt — when I played it, I thought, “This is the feeling I want.” You’re dropped in this world and told you can do anything. But it means something, because it’s Nintendo. If I run over that hill it’s going to be interesting to me. I’ll find something interesting there.

Similarly, here we want — there’s lots of footage and content. If you see something and follow a search into another search and lose yourself in this breadcrumb trail, that’s always going to be fruitful. I didn’t want people to worry that they’ll miss something. There is no filler content. There are so many scenes, but they all show you a different interesting angle on a character, some new texture. The job of piecing together this jigsaw story — it spans two years, so there’s a lot to see, a lot to infer. You see locations change with the passage of time. You see characters change. It’s a very rich set of content.

Above: Wake up.

GamesBeat: Are you ever switching between characters here, or are you always her?

Barlow: You’re always in her POV. The game itself spans several hours. She has this one evening to get what she needs out of this database. You’re with her, and the sounds of her apartment roll around you. There is this sense of time passing. She’s there as this reminder that there is a world outside of this, that you’re spying on these things and she’s watching as well. There’s an interesting texture there, where on one hand, we’re saying, “This is your computer. You’re being her.” But also reminding you that you’re not her. It’s an interesting push and pull with the suspension of disbelief that does some fun things.

GamesBeat: Is there a camera on each person’s head that we don’t see?

Barlow: Everyone is talking over a webcam or a cell phone. They’re using their own device. That in itself can be insightful, giving you some sense as to what they’re doing. The body language — when you’re Skyping someone, maybe you put the phone down and engage in a conversation. If I’m phoning my wife — when I was touring with Her Story, I was spending lots of time Skyping from hotel rooms. There was a point where I would choose where to start the Skype, making sure it was a flattering angle on me. Then I’d start talking to my wife, and maybe she’d say that something bad happened with the kids today. Then I’ll sit down and convey that I’m paying attention. A whole layer of body language comes with the fact that these people are speaking into devices that they’re handling, an extra layer of understanding what’s going on with these characters’ lives.

I’m deliberately picking the more innocuous words, just to avoid stumbling over spoilers. But you can see how you’re able to pick up on threads of the story. You’re in all these different situations where people are Skyping. The fun thing about the story is, because of this conceit, often the big plot points are happening where two characters are in the same room, when there’s no reason for them to be Skyping. A lot of big points are happening off camera, and you’re almost seeing the negative space. You see the reaction, characters talking about things after they happen, seeing the effect of those events on them. It’s interesting, because it means the story becomes very character-centric. You imagine those events playing out, so you have a real investment and sense of ownership in that part of the story.

GamesBeat: Did you ever, in a way, want to bypass part of that and have that play out in front of the webcam?

Barlow: I’m always attracted to structures where there’s a constraint. Very early on with Her Story — if we’re only ever in the interrogation room, and if we only ever hear her answers, those are constraints that create interesting gaps for the player to fill in. Similarly, here, when you look at something like that, you think, “This really cool thing is going to be happening in the story. Wouldn’t it be cool to see that?” But it’s just as cool to see the characters react to it.

My go-to example is a Shakespearean war play. You never see the battles. You see someone run in and say, “Oh my God, I just saw 300 guys decapitated, the rivers are running with blood.” You see them deal with it. It’s this very intimate character note, and you imagine the amazing battle in a much better way than they could ever have staged it. I’m definitely attracted to those moments where your imagination gets involved.

Above: Scott McCloud wrote Understanding Comics

GamesBeat: It reminds me of the book Understanding Comics, where it talks about what goes on between each frame of a comic book.

Barlow: Yeah, what happens in the gutters. For me, that’s a fundamental thing that I wanted to push into with Her Story. There’s an assumption that in video games we can see and show everything. The difference between a game and a movie is that in a movie I only see what the director points the camera toward. In a video game I can spin the camera around, and if I’m in a character’s house, I can walk to a wall, look at a poster, read something, go through all the drawers in Gone Home. We have this ability to unfurl and show everything. The end point of that would be the holodeck. That’s a lot of people’s idea of the ultimate video game. I’m on the holodeck, everything is real, and I’m just living this thing.

If I run that mental experiment in my head, that doesn’t feel like a story. I think all stories happen in your imagination. Even something as visual and specific as cinema still lives in the cut, just as the comics live in the gutter. The way in which things are cut — I’m only seeing one thing at a time. Everything that’s off camera, I’m imagining. If I see a character’s face, I’m imagining what the other character is doing while I look at that.

GamesBeat: Are you ever guessing who that person is talking to, or do you usually know?

Barlow: No, that’s one of your big initial questions. Who are they talking to? What is the context of this conversation? The beauty of this format that I’ve accidentally created is, with some of those — with, say, Call of Duty, you’re running around a battlefield, and I’m looking at a 2D image, but turning it into a 3D image in my head. I’m using two sticks to aim my face and a reticle. I’m picking who I’m shooting. I know how much ammunition I have left. I’m choosing which weapon to use. I’m also thinking about my larger objective in this map. All that stuff is going on, this huge lightshow, and that’s using up — call it 90 percent of my available brainpower. There’s not much left to process story, which is why those games will often slow down or stop and there’s a cutscene that tells the story, or an audio diary. In a BioShock game I’m going to stop and listen to an audio diary in order to absorb the story.

For me, what was attractive about this was, by meshing the literal story content with the gameplay — if I’m watching a video and listening to someone talk, I’m thinking about who they’re talking to. I’m thinking about whether they’re upset or happy or sad. Is the thing they’re saying true? All of those questions are story questions, but they’re also gameplay questions. You get this wonderful marriage of story and gameplay. The more invested you become in the gameplay, the more invested you are in the story. That becomes a very deeply immersive, involving thing. For me that’s one of the ultimate goals of telling a story, to make that real for people, to give them that involvement.

You can find yourself hypertexting through the thing at a very rapid clip. You can bookmark things, tag them and filter them. There’s a lot of stuff there to help you organize everything you’ve done, so you don’t have that fear of missing out, worrying about — oh, I need to track everything and write everything down. It’s part of just giving you permission to lose yourself in it and have this feel slightly more organic, slightly messier than Her Story. It doesn’t have that formal structure of a police interview. It should feel like it’s putting you in the heads of these characters, living these lives.

If you need to blow off steam, you can play some solitaire. I had one tester who played far too much solitaire. We had to go over and say, “You can stop doing that now.” But this is my very ambitious follow-up to Her Story. People seem to enjoy it. The tests we’ve had have all been very promising. I’m excited to get it out in the world now.

Above: Her Story goes as far as to emulate screen flare in its old-school look.

GamesBeat: Do you know when it’s coming out?

Barlow: Very soon. I hope to announce a date very soon, and the date we announce will not be too far away. We’re just making sure everything is 100 percent before we lock ourselves in.

GamesBeat: Is Annapurna doing anything at this point to help get it out?

Barlow: We’re just in the final beta process, making sure everything works, making sure we hit all the platforms we want to hit. It is what it is now. It’s all tied up. I just want to get it out before the world ends, or before politics get so ridiculous that — “I’m not sure the themes of this game are that relevant. We’re too busy trying to avert whatever disaster is coming.”

GamesBeat: There’s the privacy element here. That seems to be coming into the news quite a bit. Apple’s doing commercials about it.

Barlow: The last few years have been wild. Developing this — thematically this is very current. Things keep coming up in the news. Which is cool, because it feels like we’re actually making something relevant, but at the same time, shit, now we have to get this right. We need to make sure we’re saying something useful about this and being accurate.

GamesBeat: Didn’t you tweet something about politics and games?

Barlow: I did. [laughs] I just got annoyed. It’s funny, because it looks like — from what I’ve seen of Watch Dogs, the actual team seems to have a stronger handle on that, but it felt like some kind of PR flack putting out that Q&A. I wasn’t sure who they were trying to appease. Maybe they were trying to appears the more right-wing people. It pissed me off. There’s lots of disingenuous discussions of what it means to be political or have a political game.

I was just saying to another journalist — for me, one of the touchstones for me with this was The Conversation, the old movie. That movie came out just before Watergate, but it was born of that era, born of realizing that the government was not out to look after its citizens. There was this invasion of privacy. People were breaking the law on behalf of law enforcement. But that film doesn’t debate that issue. That film takes as a given its political stance, that Nixon-era, Watergate, COINTELPRO, all that — it’s a given that all of that is bad. The political stance of that film is not asking a question, or even being didactic. It’s just taking as a given that this is the world the story is born out of, and then we’ll look at Gene Hackman’s character.

Then it becomes a character study. What is it like to be a person caught up in this world? What it is it like to be a person on the coal face of government surveillance? That’s a super interesting movie.

Above: The user interface for Telling Lies. Can you dig out the truth?

GamesBeat: For something like Far Cry, then, you’d rather have them come out and say this right-wing militia stuff is crazy and it shouldn’t be allowed to happen?

Barlow: Again, it’s disingenuous. The way they talk about it — if you made a hypothetical concentration camp experience, there’s possibly some — I’ve read some incredible books from the perspective of people on the wrong side of World War II, how they dealt with the aftermath. Movies like The Night Porter and stuff that deal with some of that and how complicated that can be. But when you play Far Cry, you’re not walking in the shoes of someone. You’re not inhabiting the full life of someone. That’s a game in which you run around shooting people and talking to NPCs. You have a player character who’s a character in a story. There’s a plot that advances through cutscenes. But it felt disingenuous that there’s this kind of complex moral calculus going on. Because there isn’t.

If you’re going to make a game that’s about white supremacists in America, I don’t think that’s — for me the question is not, is white supremacy wrong? There are questions of how we deal with it. Maybe there are questions about what it’s like to be the victim of that, or what it’s like to be drawn into that world. There are interesting human stories you can tell around that space. But to imply that everything has to be like high school debate, that accept-the-contrary-position bullshit….

Above: Telling Lies

GamesBeat: They posited the notion that if you can play one side, you should be able to play the other side. That sounded like a bad idea.

Barlow: I’m making something here which is all about different POVs on the story, seeing things from different angles. You’re having to read between the lines and realize whether you were right or wrong as you become familiar with the story. I’m very much of the belief that there’s something to be gained from having different perspectives.

But for me, this game, without spoiling it, it definitely has an opinion. The politics we explore here–I have an opinion. The game has an opinion. It’s not about having a character stop, turn to camera, and mouth my opinion. I take it as a given that this is the world we live in. Then I’m interested in, what does that do to us? How do we escape from that? How do we deal with that? What it does to humanity, fundamentally? What does it do to our relationships? What does it do to our trust in our loved ones?

I’m trying to explore the interesting character-based things, but — I think it’s an abdication of some kind of responsibility. We have the death of the author, right? We get that these things live on in the hands of their players, and they’re free to interpret them how they like. As an author, it doesn’t mean that you’re sat there at every second saying, “This is my politics. This is what I’m writing on each page.” But you should have a sense of — even if it’s not what I’m intending to do, what have I created? What is the message of this thing I’ve made?

At some point you have to own that message, and if it’s not a message you’re happy with, you should change it. Again, I think it’s disingenuous to pretend that somehow video games are not capable of containing a message, and we have no responsibility for our message.