testsetset

Google and Apple loom so large over the field of digital mapping that it’s understandable why it may seem they represent the beginning and the end of this market. But the demands of a wide range of services such autonomous vehicles and smart cities are giving rise to a new generation of mapping competitors who are pushing the boundaries of innovation.

The fundamental approach to mapping used by the two giants, mixing satellite imagery and fleets of cars roaming the streets, is becoming archaic and too slow to meet the fast-moving needs of businesses in areas like ecommerce, drones, and forms of mobility. These services often have very specific needs that require real-time updates and far richer data.

To address these challenges, new mapping companies are turning to artificial intelligence and crowdsourcing, among other things, to deliver far more complex geodata. This increasing diversity and competition is the catalyst behind a global mapping market that is growing more than 11% annually and is expected to be worth $8.76 billion by 2025, according to Grand View Research.

“It’s a very exciting time to be building a mapping company, because the world is getting connected,” said Alex Barth, head of auto for San Francisco-based Mapbox. “And it creates all sorts of new ways of thinking about location.”

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Google Maps triggered a revolution when it was launched in 2005. The embeddable, adaptable mapping service quickly supplanted then-leader Mapquest, which had built its early lead on static maps that provided directions. In 2012, Apple broke with Google to create its own maps, which were initially regarded as a disaster, though they have continued to improve in quality.

The problem with both models is that the world around them is accelerating faster than these leaders are evolving. Indeed, the Wall Street Journal reported this week that Google Maps is filled with an estimated 11 million fake business listings, delivering a serious blow to its credibility. In response, Google said it took down 3 million fake listings last year, and continues to step up its efforts, while also insisting fake listings have existed pretty much since printed directories of businesses.

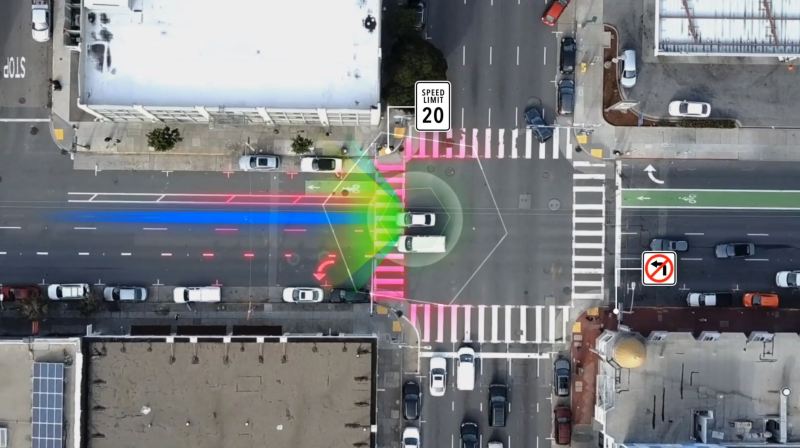

Meanwhile, the use cases for maps continues to explode. Cities are turning to smart parking, planners are relying on mapping data to make infrastructure decisions, and delivery services need more granular information that is up-to-the minute. Other businesses are using geotargeting in marketing and ecommerce. And of course, autonomous and connected vehicles need sophisticated mapping for information.

New directions

Mapbox is a good example of the new breed of mapping companies rising to meet these needs.

Founded in 2010, the company has raised about $227 million in venture capital. It originally got its start with a team that was building web and mobile tools for governments and non-profits to assist in efforts like election monitoring. But Barth explained that as they sought to add more mapping features, they realized just how shallow the existing geospatial data was. They set on the path of building their own mapping solutions, which was eventually spun out to create Mapbox.

The company provides a platform and software development kit that uses artificial intelligence and augmented reality to overlay information on its maps. Mapbox primarily then builds tools that allow developers to use its maps in their own services in a wide range of industries, including media, logistics, agriculture, government, real estate and drones. It’s being used for Snap Maps on Snapchat, the Weather Channel App, the Washington Post election results, and visualizing data in Tableau.

In addition to powering these third-party services, the maps collect and anonymize the data and feed it back to Mapbox’s main platform. The company has more than 400 million map endpoints in use, gathering a constant stream of data to enrich those maps.

“What we’re excited about is self-learning maps where the map gets smarter with how it’s used,” Barth said. “Increasingly, maps are being built automatically through the sensors these days. And they’re not being used by humans but by machines. There is a huge leap in terms of the accuracy, but also the recency of the data.”

Sweden’s Mapillary is taking a somewhat different approach to solving these issues.

“The expectations for people using maps is very different than it was 10 years ago,” said Jan Erik Solem, CEO and cofounder of Mapillary, a Swedish mapping startup that has raised $24.5 million in venture capital. “More and more companies need maps to be competitive.”

Solem founded the company in 2013 after Apple acquired his previous startup, which had developed facial recognition technology. The company leverages the vast number of mobile devices that people carry that produce increasingly richer images and geodata. Those users upload information via their Mapillary app, creating an immense database of rich information.

Mapillary then uses computer vision to analyze that data to dentify data for updating and improving maps now being used by companies such as BMW, Lyft, and Toyota. The latter is using it to fine-tune its self-driving vehicle algorithms. Mapillary also has a partnership to use Amazon Rekognition, which reads text in images, to extend its computer vision power to create services that help identify parking spaces in cities.

More recently, it launched a mapping marketplace to connect businesses with specific mapping needs and that are willing to pay for specific projects with its community of app users who are in a position to gather that information. Beyond serving those businesses, that data also gets added to Mapillary’s general platform.

“The ridesharing map is different from the delivery map which is different from the scooter map,” Solem said. “With so many devices collecting images and sensor information, maps are going to be part of the future for businesses.”

Tactile Mobility adds a further twist to these methods by gathering data on road conditions via sensors and software embedded in vehicles. In addition to the ability to use cameras to see objects, autonomous vehicles need to be able to “feel” such nuances as bumps, potholes. water on the road, and the curve of a street. The company has developed a system it calls SurfaceDNA, which adds this information as a map layer.

Smarter cities

While many of these maps are being used to power various geolocation and mobility services, they are also playing a growing role in transforming cities.

Israel-based Moovit has been building crowdsourced maps of urban transport systems since its launch in 2012. Much of the data is generated by almost 2000,000 people called “Mooviters,” who contribute information about local public transportation services.

In 2017, the company opened up its data to cities who could use its tools to improve public transportation. Called the Smart Transit Suite, the service can be licensed by local governments who can then tap into the data to help policymakers better understand how to manage their transit systems, plan construction projects, and analyze more precisely how people and vehicles are flowing around their city. In turn, cities can make this data available to their citizens and local companies in various forms.

Moovit has now raised a total of $133 million in venture capital, including a $50 million round last year led by Intel Capital.

“We want to make mass transit more reliable,” said Yovav Meydad, Moovit’s vice president of products and marketing. “We think there’s tremendous value in this data for local decision makers.”

Google’s Waze has been also working more with public transit agencies to share its data for public planning purposes. The company recently expanded a Smart Routing program with the city of London to help reduce pollution by making it easier for drivers to follow tougher new rules tied to reducing emissions.

Meanwhile, San Francisco-based Streetlight Data is helping city planners by assembling data from trillions of location-based services (LBS) and GPS and cellular data points. This data comes from a variety of public and private sources including cell phone data, car navigation data, commercial truck navigation systems, and partnerships with various mobility companies. The result is a platform that offers insight into travel patterns for cars, bikes, and pedestrians.

“I could look at any city for the last year or two and tell you basically the volume of growth of traffic between cars and bicycles, weekend versus a weekday, from a football game day as opposed to a normal work day,” said Martin Morzynski, Streetlight’s vice president of marketing and product management. “It gets pretty deep into detail.”

The data can distinguish, for instance, cohorts of commuters as they move through various stages of trips, from walking to taking shared scooters, to getting on a train and then catching an Uber. Some clients are using it to optimize parking lots or design new bike networks.

But on a larger scale, the data enables transportation planners to make more informed decisions about new projects. That includes both building new infrastructure and allowing new forms of mobility. Traditional transportation studies can take months, and they miss many nuances in terms of the types of vehicles using roads and their origin and final destination.

“It’s a massive investment in this infrastructure about where they place it and how they design it,” Morzynski said. “This kind of data comes to the rescue to help them figure out how to do it.”

Going mobile

Some mapping companies have begun leveraging their own maps to push into other mobility services.

City transport app Citymapper launched its own commercial bus service in July 2017. Based in London, Citymapper had started trialing its own smart bus and transport service earlier that year. It operates much like a traditional bus service with fixed stops, though the buses have amenities such as USB chargers and contactless payments. The bus service used the mapping data to identify routes that are underserved.

Here Technologies, which has developed the Here open mapping platform, announced in January 2018 the creation of a new subsidiary called Here Mobility.

The service includes the Open Mobility Marketplace, software designed to create a hub for all mobility services operating in a region. By centralizing and unifying the operations of all mobility services, Here Mobility believes it can expand the market for all companies that plug into the platform, while also ensuring that cities will be better able to monitor and control the services so they increase efficiency rather than create more chaos.

In addition, Here Mobility offers a dispatch service that helps manage fleets of trucks and buses by tapping its data and analytics to make them more efficient.

The company says at the moment, it’s proving difficult for many cities to truly realize the benefits of the mobility revolution because the different services are operating in silos, unconnected and independent, which has led in some cases to more waste and chaos. Here Mobility believes it can harmonize these different modes and help cities move forward.

“We are building the future of mobility,” said Liad Itzhak, senior vice president of Here Mobility. “The world is shifting from car ownership to mobility as a service. The idea is appealing to everyone. But to get to this future, we have to efficiently use all resources.”

Up in the air

While much of the mapping is naturally still terrestrial based, the exploding market for commercial drones has added some urgency to creating or extending mapping capabilities to the skies.

DroneDeploy wants to make the power of drones more accessible with its platform that automates much of the work involved. That includes scheduling times and flight itineraries, data collection, mapping, and analysis. The company partners with drone makers and allows developers to write apps for the platform.

The platform is driven by a drone mapping program the company developed. The enterprise software works with most commercial drones by allowing them to plan automatic flights, process the data via its cloud service to create 3D maps, and rapidly analyze data. The platform can even build real-time maps as the drones are flying.

The company has now raised $56 million in venture capital and has customers in 180 countries, notably in such industries as solar panel operators, mining, and construction.

DroneDeploy CEO Mike Winn said that for now, humans are often the most expensive part of the drone service, given the time it takes to draw up flight plans and analyze data. But, he said, AI and growing amounts of mapping data can help reduce this reliance on people.

“The future of drones is automation,” he said.

But the challenges extend beyond automation of a single drone to the issues raised by a sky one day filled with unmanned flying vehicles.

To make this evolution more orderly, AirMap, based in Santa Monica, California, has created an Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) platform for drones to help them navigate the complex regulatory and geographical challenges they encounter when flying.

In part, AirMap works by melding mapping technology to sophisticated databases it has created of public regulations around drone use. According to AirMap CEO David Hose, these regulations can be very complex and very specific. For example, limits on how close a drone can fly to a school means that a drone operator needs to know where every school in a region is located as the machine is in the air.

Such regulations threaten to sharply curtail the adoption of drones, Hose said.

“The aviation industry thinks of these as aircrafts,” he said. “And so they publish all these rules. Historically in aviation, that worked really well. A trained pilot studied all the regulations and learned all the rules. But drones are coming from the consumer electronics industry, which moves a lot faster. And in consumer electronics, this approach to rules doesn’t work so well.”

By having a database of rules defined by maps and geography, then, the drones can recognize their location and avoid crossing into areas that would create some kind of violation. The service would allow drones to register so their flight plans can be shared. That enables the drones to be aware of what other drones may be flying in the area, and gives air traffic controllers a clearer view into the aerial traffic.

Hose said given the predicted number of drones that are expected to be delivering goods, monitoring security, and helping emergency services, the only way to ensure that future is safe is if the machines have precise data about their rules and location.

“AirMap is really pushing around the world to prove the advance uses of drones,” Hose said. “Our belief system is that we will live in a world where drones are flying all over the place. But to do that, you have to have clear rules and the regulations of all the drones in the system. And the only way that will happen is through automation of regulations and maps.”