Time means nothing when you’ve created something special. Jordan Mechner launched Prince of Persia in 1989, when he was 25. And 30 years later, he is still talking about the franchise that inspired and delighted gamers for what seems like an eternity in video game history.

Forgive the cliche, but for many fans, Prince of Persia is timeless.

Mechner spoke about the franchise and what it has been like to create art cross video games, film, and graphic novels over the decades in a fireside chat with game developer Fred Markus at the Gamelab event last week in Barcelona.

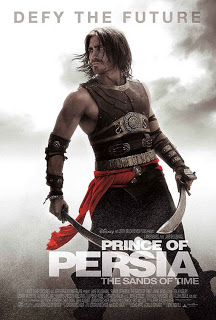

The success of Prince of Persia helped Mechner stay in games for decades working on titles such as Karateka, and it gave him a chance to write graphic novels as well as do films. Mechner worked with Jerry Bruckheimer as a writer on The Prince of Persia: Sands of Time film, which grossed more than $336 million after in debuted in 2010.

And during the fireside chat, Mechner said he was working on a book about his original notes from working on the first Prince of Persia game. Here’s an edited transcript of their fireside chat.

Above: The original Prince of Persia debuted in 1989.

Fred Markus: It’s been 30 years, right? For Prince of Persia?

Jordan Mechner: Yes, this is the 30th anniversary year of the original Apple II Prince of Persia. 30 years ago I was at my Apple II trying to get to alpha.

Markus: And that’s how it started. Did you start with games, or did you start thinking about other things before you worked on Prince of Persia?

Mechner: Yesterday, after dinner, I was talking with Rami Ismail about how people only see the published, successful games on our resumes. But like most of us, by the time Prince of Persia was published I’d been making games for 10 years. Since I was in high school, when I got my first Apple II computer in 1979. I started making games, first in BASIC, and then in assembly language. I made a ton of games that were never published. I worked hard on them — I worked for a whole year on an Asteroids clone, trying to make it as much like the arcade version as possible — but then Atari told publishers we couldn’t do that. We couldn’t publish copies of their games. That never got published.

I spent my first year in college making a game called Death Bounce, which was like Asteroids, but just different enough that I thought I wouldn’t get sued. I sent it to Broderbund, my favorite publisher. Broderbund’s founder, Doug Carlston, called me. This was my first real contact with the game industry. I was in college in my dorm room. This was before the internet. All these game-makers and publishers were just names I’d seen in magazines, or on the title screen of a game.

Markus: Broderbund was a big [publisher] at the time.

Mechner: Yeah. I got a phone call while I’m lying in my college dorm room. It was Doug Carlston. He said, “Hey, I got your game.” I’d mailed it to them on a floppy disc. “It’s well-programmed, but the game industry has moved on. This year the public likes a different thing.” He sent me a copy of Choplifter. Anybody here remember Choplifter? This blew my mind in 1982. It was the first game I’d played that told a story. Asteroids, Space Invaders, you had three lives and you had to get a high score. All of that was based on the business model of putting quarters into machines. Choplifter told a story, and at the end it said “The End.”

That was the inspiration for my next game, Karateka. I worked on that for two years. It was a fighting game, a 2D side-scrolling fighting game. But it was a story. You were supposed to rescue someone. I don’t even know if there were fighting games at the time. It was 1984. There was Swashbuckler?

Above: Prince of Persia: Sands of Time had wall running.

Markus: Konami had Yie Ar Kung Fu a very long time ago.

Mechner: Yeah, they came out about the same time. And so Prince of Persia was my next project after Karateka. By then I considered myself a veteran of the industry at age 21. Although most of the stuff I’d done hadn’t been published. I was also kind of torn between thinking, “Should I keep making games?” Because I also loved movies. I wanted to be a screenwriter. I wanted to do animation. If the Apple II hadn’t come along when it did, or if I’d been born 10 years earlier, I probably would have tried to be a comic book artist or a film director. That was my dream.

What was so great about the Apple computer was it put into my hands the power to make a game, which was like an interactive story. Creating that fantasy in a world that people would hear about and play. And the industry was so young that there wasn’t that much of a gap. Star Wars came out in 1976, and when I tried to make my little Super 8 movie, obviously it wasn’t as good as Star Wars. Anybody could see that a kid had made it. But the games I was making in assembly language, in high resolution, there wasn’t that much of a difference between my games and the published games, which at the time you bought on a floppy disc in a ziplock bag. It felt like it was within reach.

Markus: The medium was in a place where you could put your own titles out there and not look completely outdated. When Karateka and Prince of Persia came out, they were pretty breakthrough titles in terms of visual and story. Then you got Prince of Persia published?

Mechner: Yeah, Broderbund published Prince of Persia. It’s interesting. Our subject today is kind of different media, and games being one. You could even say that games are many media, because today’s triple-A games, multiplayer games, mobile games, they’re all very different. They’re different art forms and different business models from those early games that we sold on floppy discs.

After Prince of Persia shipped on the Apple II, I’d spent 10 years of my life in front of an Apple II screen. I really wanted to try to pursue film. I’d spent a year in between those two games, in between Karateka and Prince of Persia, writing my first screenplay. It didn’t get made. It almost got made, which was very exciting for me at the time. But ultimately it also taught me a lesson, which is that a film takes so many people, and to make it you need a producer, a studio, someone to put up the money.

The great thing about Prince of Persia on the Apple II was that — if the movie I had written didn’t seem to be happening, I could just go back and keep working on the game. I could push that forward all by myself. That’s still the case today. In a way, it’s even more the case, because there are so many great tools available now. It’s harder to make a game stand out now, out of the thousands of games that are released, but the tools to make something amazing are in everyone’s hands.

What’s rare is the real innovation, the leap forward, but it still happens. Yesterday we had Brendan Greene talking about how he came up with PUBG, which was all about the idea. He didn’t have incredible means at his disposal to create that. Minecraft, a few years ago, is another one. There are still ideas out there waiting to be had, to happen.

Markus: You were 25 when you published Prince of Persia?

Mechner: Yeah, I was 25.

Markus: And then it was 14 years until the next one. During those 14 years, did you go back to movies?

Mechner: At that time, movies — the convergence we talk about now had not yet happened. Making games happened on the PC with floppy discs. Online was barely starting to come in. Movies were on 16mm film. You needed a camera and a film lab. You were cutting and splicing celluloid. It was a completely different craft.

After Prince of Persia, I went back to New York, where I’m from originally. I went to film school. I spent a year learning how to shoot and edit on 16mm film, and do sound. I made some short student films. But the connection with video games wasn’t there. The teachers at film school, they would look at Prince of Persia and say, “What is this?” To me, it has cinematics. It’s telling a story. They’d say, “No. We’re making film here. Listen to us.”

Likewise, while making games–what I was learning about camera angles and so forth didn’t really play in making games yet because there were no camera angles. Prince of Persia has one camera angle.

Above: Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time was a blockbuster movie in 2010.

Markus: The movie industry was only just going digital. George Lucas was starting to bring that in slowly, but there wasn’t a direct link. Movie guys didn’t know what they were looking at when they saw computers and video games.

Mechner: Broderbund wasn’t far from LucasFilm, up in San Rafael, California. As a teenage Star Wars fan who stood in line to see Return of the Jedi on the first day in 1983, I got to go visit the Skywalker Ranch. Steve Arnold, he had on his wall a framed rendering. It was the first render I’d seen. I was making 280 by 182 pixel graphics, and then I saw what looked like a photograph of the road, Lucas Valley Road, going up to Skywalker Ranch. Then I thought, “That’s not a photograph. That’s computer graphics. What?” They were doing something called raytracing.

Markus: That was in the ‘80s. Lucas was probably the only company that had its hands in digital graphics at the time. That was the only link at the time between movies and the digital world.

Mechner: I got away from your original question. But yeah, in those 14 years I went to film school. I made some short films. At the same time there was the sequel to Prince of Persia, Prince of Persia II: The Shadow and the Flame. I did that remotely. The team was at Broderbund in California. That was the year I spent living in Paris. I wanted to travel. I learned Spanish and French and I spent the summer shooting a short film in Havana, Cuba. That was the year after the Soviet Union had withdrawn support, so Cuba was in economic crisis. We went down there with 16mm cameras and shot a film.

I was trying to get out into the world, get out of the industrial park, get out from behind the Apple II. At the same time, in Paris, where we edited this short film, I had a PC, which blew out the electricity in our building. But it was still on floppy discs. I edited the levels for the game and sent them by DHL to California. Every few days a DHL packet would go back and forth for the team.

Those two threads came together when I made — I founded a team to make a game called The Last Express in San Francisco. It was a game set on the Orient Express in 1914 on the eve of World War I. It was a CD-ROM adventure game, and so to make it we actually had to do a film shoot. We had a cast of actors and costumes which we rotoscoped. I didn’t mention rotoscoping, but that was a tool to do the animation, first for Karateka and then Prince of Persia, to make it more realistic.

Markus: You used that in Karateka?

Mechner: Yeah, yeah. Karateka was on Super 8. I filmed my karate teacher doing punches and kicks. I projected the frames and traced them on tracing paper. Getting those framed images onto the Apple II — this is ancient history, probably beyond the scope of this discussion, but by the time of Prince of Persia, VHS had come in. I was able to videotape my brother running and jumping and climbing and doing all these things. Again, it was a painstaking process to digitize those frames.

For The Last Express, we created an automated digital rotoscoping process, which took the thousands of frames of the film shoot and turned them into something that looked like pen and ink drawings. I was really inspired by comic books at the time, European comic books. Enki Bilal, Hugo Pratt. I loved comics growing up, but they were American comics, a totally different thing. When I went to France and saw the kinds of adult stories that comic books could tell with these beautiful visuals, that was really inspiring. With The Last Express, part of the inspiration was to make an interactive, fluid pen and ink animated comic.

Markus: It was the first time you encountered this big breakthrough, that movies and games could merge for you.

Mechner: It was the first time I felt like I was using what I learned about screenwriting, directing actors, doing voice recording, camera angles, storytelling. It felt like I was using what I learned about film in a game. But at the same time, a game is a completely different kind of storytelling. A film is a story where you, as the filmmaker, as the editor, you control everything. You create suspense and pacing. You’re telling one story. In a game you’re creating a world where the player can choose how to move through it at their own pace.

Markus: As you were mentioning before, the player is controlling time, how much time they’ll spend in a room somewhere, for example.

Mechner: Even more so today. In a multiplayer game you can decide how long you want to hang out in a particular area, seeing what’s to be found. Or you can just go ahead and get into something different. That’s what’s so challenging about storytelling in games. In film you have control. You can work on it for a year and get the pacing just right. “It’s a little boring in this part, so let’s make it shorter.”

In a game you create an engine that players can use any way they want. They can break it. If you play in a certain way and you’re bored, that’s not the player’s failure, it’s the game designer’s failure. You want to create an engine that players will use to create, just by naturally playing, their own stories. The great thing about something like PUBG is it works really well at that. The stories that get naturally created are thrilling. They have that dramatic pacing and a lot of variety.

At that point, it’s actually worth recording your game session and posting it, which is another new medium now. It’s a subset of film and TV, these recordings of games made by players.

Above: Karateka

Markus: Sands of Time had a lot to do with the handling of time. When that happened, you were working on a big triple-A game with a big triple-A publisher. You even had Disney involved. Suddenly there was that convergence really happening, where you had both a game and a movie going on.

Mechner: Sands of Time — I think it was 2001 when I went to Ubisoft, and 2003 when the game shipped. For me, that was the moment when these two or three threads of my professional life really came together. The first Prince of Persia, the 2D Prince of Persia, at the time it was a dead franchise. Today there’s a resurgence of retro gaming, where you can find and play old games online, but that wasn’t so much the case in the PlayStation 2 generation. We were making a new game for gamers who, a lot of them, hadn’t played and didn’t know about the first Prince of Persia.

Markus: And it was another visual breakthrough.

Mechner: How many people out there played Sands of Time? That was a great project with a great team in Montreal. A young team, too. The challenge was really — let’s make a new game that’s Prince of Persia, but set ourselves free to try to see what would be fluid, dynamic navigation now.

If you just transpose the Prince of Persia moveset to 3D, like we tried to do with Prince of Persia 3D a couple of years earlier — actually, the first Tomb Raider in the PSX generation, that had the Prince of Persia moveset. You can step forward, run, and jump. But just by itself in 3D it didn’t have the fluidity of the 2D games, where you can chain a lot of movements together and feel the thrill of being a character in an action movie. It’s like Indiana Jones in the first 10 minutes of Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m jumping, missing the ledge, grabbing the vine.

With Sands of Time, taking it to the vertical was the breakthrough that made that possible. You could run on walls and rebound. That was a great project.

Markus: And then you worked with Disney as well.

Mechner: I worked in Montreal with the Ubisoft team on the game, and then I went back to Los Angeles and pitched the movie to Jerry Bruckheimer and Disney. The Prince of Persia movie was happening. That was really when time came full circle.

Markus: That was when you were finally able to work in every medium you’d experimented with. How did you feel games fit into storytelling across all these different media?

Mechner: They’re all very different. Each one of those things is a different craft, and there are so many individual crafts now that go into making a game or a movie. I’m not an animator by the standards of today. I’m not a programmer. All of those were just means to an end. I was able to get good enough at those individual crafts to make a game in 1989.

On a film you multiply that by 10. The person who makes the armor that the Persian warriors are going to wear, that’s a lifetime of craft, of studying history and costume design. How do you hand-tool leather? How do you make weapons out of different materials?

Above: Karateka

Markus: It’s all specialists in their domain.

Mechner: Right. To be on the set of the Prince of Persia movie when it was shooting in Morocco, with actual camels and horses and hundreds of people in costumes — to think that this is what making those little sprites on the Apple II had led to, it was kind of overwhelming.

I actually didn’t have much to do at that point. I had written the first version of the screenplay. I got the movie going. But by the time it was filming, I was the first of maybe five screenwriters that came after me. Jerry Bruckheimer especially is known for having a lot of writers work on a film. Everybody on the set has a job to do. It’s a well-oiled machine. People are moving lights, herding camels, closing up tends, sending trucks ahead to build the next camp, and I’m just the guy who made the game and wrote the first screenplay. Why am I even there?

To keep busy on the set I took my sketchbook. Sort of like the set photographer, whose job was just to take pictures of the madness. It looked like the Exodus, hundreds of people going across the desert. Here’s this Persian warrior who’s taken off his helmet and sitting drinking water in a tent, next to all these TV screens. I’ll sketch that.

Sketching for me is a kind of Zen. There’s something about — the scale of time on these projects is so different. If it’s going to take a year to make — sometimes it’s 10 years from the very start to the time the public actually sees something. The great thing about a drawing is — in the time it takes to pick up a guitar and play a song, you can pick up your pen and do a sketch. The sketch is like a record of those three minutes.

Markus: The first time I met you, we were in France and I was fishing by the river. You were behind me, and you were actually drawing me fishing. I saw that drawing not so long ago. The interesting thing about your drawings is that they’re very mature, very pure drawings. They’re not noisy or complicated. The purity of the lines, the silhouettes, people’s faces — we were talking about how design is not about adding things. Good design is about removing until you get to the essence of what you’re working on. I found your drawings very much like that.

Mechner: Often, when I have more time to do a drawing — the more time I can spend on it, the more flaws I see in it. As it gets more realistic, I can see, “Oh, I didn’t get the shading quite right. This is a bit out of proportion.” That’s where the fact that I’m not a trained artist becomes more evident. But if it’s just a few lines, it’s kind of magical. Somehow our imagination fills in everything that’s not there. With a couple of lines you can suggest something that communicates more than a more detailed drawing I spent an hour making. It’s like that with games, too.

Markus: Or writing, or comics. Comics are the same way.

Mechner: In comics you have all kinds of styles. Some of the most popular comics of all time, like Charlie Brown, are really simple drawings, and yet they’re universal. Some very, very detailed, realistic comics are amazing too, but there’s a — our imagination somehow enters into something very simple in a way that — the more lifelike it is….

Markus: Pixel art wasn’t called pixel art at the time. It was just what we could do.

Mechner: When you say, for example, that the animation in the original Prince of Persia or Karateka was fluid — it’s eight frames per second. The character is 40 pixels high. The player’s imagination is bringing so much to it. But then suddenly you say, “Okay, we have all the pixels in the world, all the sound effects, and we can make this look like a movie.” That’s a different challenge. You get the uncanny valley. “It almost looks like a movie, but there’s something wrong.”

Markus: That’s the incredible choice that the last Legend of Zelda made. They had that conversation for a very long time about the visual style of the game for these reasons.

Mechner: I loved the new Zelda. When you were talking about the GDC talk the designers gave — they showed all the different visual styles they tried for Zelda before they arrived on what they used. They had more photorealistic ones, but they ended up coming back to this cartoony, cel-shaded look. In their words, it’s an art style that lets you lie. You can shoot a deer with an arrow and it turns into a snake. That’s pretty different from the Red Dead Redemption experience, where you have to skin the animal–

Markus: If you want to leave room for weird stuff and not break that barrier of photorealism, you have to find a style that allows you to communicate that. That’s where there is that link, that difficulty of choosing what you’re going to do. Are you going to go fully realistic? Are you going to leave room for the imagination? We see that in a lot of indie games.

Mechner: Finding the right visual style, the right language, is key. When it’s just right, as in Zelda, so many other things become easier.

Markus: Another thing that’s changed through the time period we’ve been working in the industry is the arrival of massively multiplayer games, or not so massively multiplayer games like PUBG and Fortnite. All these games that let the player go and make their own story. What do you think about what’s happening to storytelling in games?

Mechner: Games aren’t just one medium. It’s a whole range of media. New ones are being born all the time. A multiplayer game isn’t just — there’s the story of the universe, whatever story or lore the designers have created for the world. Then there’s the stories of individual missions and characters that the designers created for players to discover. But more than that, there’s the story of the player playing the game. As with PUBG, the rules can be very simple, and yet the player’s story can be very powerful.

The success of games in which players have more creative power to have unique experiences that no one has had before — you feel like by playing the game, you’re creating something. That’s hugely powerful. All the technology, plus of course mobile technology connecting billions of people together — it seems like that’s the direction that naturally, as people, we want to go. We want to share these experiences.

Above: Ubisoft published Prince of Persia: The Forgotten Sands in 2010.

Markus: We want to keep the story going. Pokemon Go is something like that. Everyone has their own story about playing Pokemon in their youth, and then Pokemon Go arrives. It doesn’t have fighting or anything else like that in there, but you still want to perpetuate your story.

Mechner: There have been incredible stories about Pokemon Go. “I was out at three in the morning and these teenagers were following me in a bad neighborhood, and a cop came over and was about to arrest them, and they say, ‘No, we’re looking for Pokemon.’” Here are these people who would normally be opposed to each other, and they’re united by this game.

Markus: When it came out, I was living in a village in the south of France, with almost no one there. At 6PM, everyone’s gone home. But when Pokemon Go came out, for a month I could go outside at 10PM and it felt like it was a village full of zombies. Everybody was walking around. There were parents with their kids, kids running around. It was dark, the middle of the night, and you could see people walking around in the light of their phones. I’d never seen anything like it. The impact of a player’s story and the meta-story of Pokemon kept on going.

Mechner: Something you mentioned before that we touched on is the way that time functions differently in different media. We talked about how players control their own experience of time in a game. Even in what we call linear media, though, it’s interesting how differently time functions, and how so much of the craft revolves around that.

In film, editing and pacing changes everything. You can have a longer cut of a film that actually feels like it goes by faster. There’s not a dull moment, but it’s actually 20 minutes longer than a shorter cut where you start to feel bored. It’s because of the subtleties of how — through sound, through choice of camera angle, through editing, that’s a big part of the art of filmmaking. It’s really the art of editing. TV is cinematic, and it’s sort of the same craft, except that you’re telling a story — instead of telling a complete story in the space of two hours, you’re telling it over maybe 60 or 70 or 80 hours. It’s a long form. There’s a whole different rhythm.

Markus: And you have a teaser at the end of a show all the time. I don’t know if you’ve read the Tintin comics, but at the end of every story, the last double page is about what’s going to happen next, the cliffhanger.

Mechner: Comics, graphic novels, is another form of storytelling that’s very different. I found that out around the time of the Sands of Time game. That was the first time I actually wrote a graphic novel script. It was for an anthology prequel to the movie. Disney had the idea to do this, and I volunteered to write it. I’d loved comics since I was a kid, as I mentioned. That’s probably what I would have kept on doing, had I not been the right age to get excited by the Apple II.

That was the first graphic novel script I wrote. I got to work with six great artists. The idea was that each of them did a chapter. Part of the challenge was to create six stories with a story, kind of like the 1,001 Nights, to justify the fact that each was in a different art style. But that was the beginning of my education in a completely different medium.

Then the first really big one was Templar, a book I wrote about the Knights Templar in the 14th century. It was a swashbuckling adventure story. The illustrators, LeUyen Pham and Alex Puvilland, taught me a lot about how to tell a story on the page. My first draft was — I was coming out of movie screenwriting. This could work in a movie, but in a graphic novel they would thumbnail it and storyboard it in a different way.

That was a whole new apprenticeship for me in how time doesn’t work at all in the same way. For one thing, you have a page, or a two-page spread actually, and the reader sees it all at once. All you can do as the artist is guide and suggest to the reader how long to spend on a particular panel. People read the words, but you don’t guarantee that they’re going to spend any time looking at the image that you’ve taken a full day to draw with all this incredible detail. They could skim right over it. Other pages they might linger on. The reader can turn back.

Markus: They have full control.

Mechner: Right. And reading a book the second time is not the same as reading it the first time. In a sense it’s almost like a game in that you’re creating something that’s going to be experienced by readers at their own pace, in their own way. But it’s still linear. What you put on the page is going to be exactly the same every time. But time is still critically important. The parts that you read fast versus the parts you read slow.

Above: Prince of Persia: Sands of Time

Markus: When I moved to the mobile industry, it’s interesting, because time is of the essence in mobile games. You can have games that can be experienced for 30 seconds. Three minutes might be all the time you have to play. When you don’t know if the bus is going to come or not, you might have three minutes. You might have 30 minutes if you’re on wi-fi at home. People also play while they’re watching TV or doing something else at the same time. If there’s a break or a boring part in a TV show, they’ll pull out their phone and play something quickly. It’s another completely different way to deal with time.

Mechner: Before we take questions, I do have one announcement I want to make. It’s a small announcement. We mentioned it’s the 30th anniversary of Prince of Persia. It’s not a new game! The thing about games and movies is they take a lot of people and a lot of time. I’m just part of the picture. But it’s a book.

I kept a journal 30 years ago when I was making Prince of Persia on the Apple II. I didn’t think anybody would read it. But a few years ago I posted it online and released it, kind of self-published it, as an Amazon book. It’s gotten a great response. Just through good timing — I was wishing that I had something to share in this 30th anniversary year for Prince of Persia. Stripe Press called me and said, “We’d like to reissue a hardcover collector’s edition of the making of Prince of Persia.”

In fact, the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York has the collection of all my old sketches, the original VHS tapes and floppy discs, box art, all of the artifacts of that era. It was really nice of them. I had a garage full of stuff that was taking up space, and they kindly took half the contents of my garage back to New York. They’re going to make those archives available. We’ll be able to do an illustrated edition of the old journals, showing the work in progress.

Markus: So it’ll have new content, stuff people haven’t seen before.

Mechner: Oh, yeah. This is stuff that even I haven’t seen. This is the interim versions of Prince of Persia on one floppy disc, where the next day I replaced it with another, but I stuck it in a shoebox. The Internet Archive took those discs and they have this amazing hardware that somehow copies the image, even of a protected disc. They’re putting all of this online slowly. Not just Prince of Persia, but all the old Apple II games. It’s amazing what they’re starting to put up there. I can play games that I haven’t seen, literally, in 40 years. Even games where 20 copies were sold total.

Anyway, that’s what the book is going to be, an illustrated collector’s edition of the making of Prince of Persia, the journals. We’re going to try to get to alpha by September, which is when the Apple II Prince of Persia went alpha 30 years ago, and ship the book by the spring, the spring of 2020, which is when the PC version of Prince of Persia shipped. That’s the little announcement.

Markus: Do you have sketches in there, or?

Mechner: We’ll see how feature-rich we have time to make it. But it would be fun to incorporate artwork into it. We want it to be authentic artifact of the past. Not to go back and analyze and re-create history, but to just — to me part of what’s interesting about the journals is that I was wrong, all the time. I would say with confidence that I’d be done in three more months. Cut to one year later: “I’ll be done in three more months!” There are entries where I said, “I’d better hurry up and finish this game, because I don’t even know if there’s going to be a games business this time next year.” This is in 1987.

It’s interesting to see how, when we’re in something, we don’t have the same perspective. Looking back, we tend to edit our memories so they make sense and it’s all part of a coherent story, like the one we’ve just told, as if our lives make sense. But with a journal–when you’re in it, you can’t see it.

Markus: It’s an important notion. When you look back at things, you see the end result. You don’t see everything that happened before. Even as you’re watching presentations of triple-A titles or anything like that, you don’t see everything that happened in the back. And since we’re all entertainers we don’t talk about it. We don’t talk about the nightmares.

Mechner: A lot of it we can’t talk about.

Above: Prince of Persia on the Apple II.

Markus: Yeah, we can’t, legally.

Mechner: Rami and I, last night — Rami tweeted this. He said, “We should all publish our shadow resume, all the projects that failed, the ones that never got published, the ones that sucked, so people can see this and get a more realistic picture.”

Markus: I would get killed by so many companies. It would be scary.

Mechner: We got tweets back. Some people said, “My shadow resume would look like this: NDA, NDA, NDA.”

Question: What would be your advice for people who want to make games, to somehow, someday tell the story that they have in their mind? Or a TV show, or a movie?

Mechner: It’s easier to make a game than it is to make a movie or a TV show. If you’re an indie developer, if you use the tools at your disposal, make what you can make. You might imagine some huge triple-A universe in great detail, but make the version of it that you can make. With a TV show or a movie, write the script. Write a spec script or a pilot describing this world and put it out there, see who responds.

Question: You’ve talked about your fascination with time and its behavior in different mediums. Sands of Time was very much an exploration of time behavior and time control. What would you do nowadays to keep exploring that subject?

Mechner: Every project dictates its own — the rewind in Sands of Time, which you’re talking about, that was a response to a constraint. In an earlier, more primitive version of the rewind–in The Last Express there was a clock, and when you reached a dead end in the story you could rewind a little bit or rewind a lot.

The reason for that was our feeling that when you die, it says “Game Over,” and the player has to restart, you’ve broken the continuity of the experience. It pulls you out of the world. The rewind was a way to stay in the story longer, to stay immersed. Even though you’d made a mistake, you could keep playing. After Sands of Time there was a whole generation of indie games that use time in all kinds of brilliant and clever ways. I think the best ones are really tied to the game itself. It makes sense for that game, but it wouldn’t necessarily make sense for another game.

As far as Prince of Persia is concerned, time has always been a theme of the series. There was the hourglass in the original game. But again, that 60-minute timer — you have to save the princess within 60 minutes or it’s too late. That was a way to deal with — we didn’t want people to be able to play forever, but we also didn’t want to punish them by saying, “You’ve played for 20 minutes, now start over from the beginning.” Plus the fact that time — timed puzzles, slicers, and spikes and things like that, on the micro level are so key for that kind of running and jumping action gameplay. That made it a natural fit.

Question: We’re in the middle of a renaissance for classic games from the early 2000s, like World of Warcraft. Can we look forward to a return for Prince of Persia?

Mechner: As I said, I don’t have anything to announce today except the book. But I would love to replay those old games.

Above: Fred Markus (left) and Jordan Mechner talk about Prince of Persia at Gamelab.

Question: You’ve been a writer for Prince of Persia games, the movie, graphic novels. Which one would you say was the most challenging as far as adapting the prince’s story to different media?

Mechner: The movie screenplay was a challenge, because that was the one time it was a direct adaptation. For Sands of Time, the game, it wasn’t adapting the story of the original Prince of Persia. It was creating a new story that was custom tailored to that game and that team. The rewind, the parkour, we knew that was the gameplay. Then it was a matter of coming up with a story that would put that gameplay in the best possible context, that would highlight its strengths and minimize its weaknesses.

The fact that the story of the Sands of Time game takes place in a destroyed palace, where all the characters other than the Prince and Farah are sand monsters, that was a choice we made because our engine couldn’t do crowds of living, breathing, interacting people the way that you can in the modern generation. It was convenient that everyone you ran into was a sand monster who was trying to kill you. The fact that the palace was destroyed — what’s the point of being able to do parkour and run on walls if you can just take the stairs? The staircase has been destroyed by an earthquake, so now you have to find a creative way to get up that broken flight of stairs. In that case the storytelling was a pleasure. It was easy. “Let’s find the story that works best for a game.”

Adapting that to a movie, I guess, was a challenge because — if this was going to be a Disney, Jerry Bruckheimer summer movie, it’s not going to be a story about two people going through a destroyed palace. Resident Evil was a horror movie and that worked fine, but we weren’t making a small, low-budget horror movie. We were making what had to be this giant thing. It had to have ancient Persia. It had caravans and armies, all of that stuff. Okay, how do we come up with a story that takes advantage of what movies can do, and especially what Jerry Bruckheimer can do, but somehow still tell the story of the game? How do we make it feel like it’s somehow still Prince of Persia, and somehow still Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time?

We have a dagger that can turn back time. But what could be more un-dramatic in a movie than a hero who goes through the movie, and any time something bad happens, he can just press a button and undo it? That’s nice to have in a game, but in a movie you can only do so much of that. Changing the rules of the dagger, so it only has a very limited amount of sand, and adding a journey aspect to the story — again, the movie evolved a lot from the first screenplay that I wrote. You can read about it on my website, if you’re interested. But it still kept the same basic structure of the story.

So, to answer your question, adapting a game story into a linear two-hour movie story was a real challenge.

Markus: The constraints just aren’t the same. The game engine’s constraints, you match the story to that. But a movie’s constraints are completely different. You have to adapt to the medium.

Mechner: Different constraints and also different opportunities. You don’t want to just do something within the constraints. You want to do something that’s going to be awesome in the way that only that medium can be awesome.

Question: When you worked on the original Prince of Persia, you did it all by yourself. You didn’t have any creative constraints. Nowadays, if you wanted to develop a new game, you’d probably need to work with a lot of people, other creators, marketing, whatever.

Mechner: And a ton of money.

Question: Yeah, a ton of money. Game development is a different world now, even for indies, compared to that time. How do you feel about that? Did you prefer that long-gone era?

Mechner: It’s a trade-off. Making a triple-A game or a big movie is thrilling. It’s like a huge circus. It’s great. I feel really lucky to have experienced that. Also, the creative collaboration with so many people who bring a lifetime of experience to their crafts, it’s amazing. I would never want to give that up.

But just to stay sane, in the midst of these projects that take years and are out of my control in important ways, and the way they turn out involves a lot of compromise with reality — it’s refreshing to be able to do, for example, a graphic novel, which is a collaboration — on Templar I was the scriptwriter, and I worked with a husband and wife team of artists, as well as a colorist and an editor. That’s a team that’s small enough to fit around a table in a café. We worked together for four years. That’s very intimate.

To be able to do that at the time when the movie and these other things were happening — I could say, “Okay, what happened today on the movie is crazy and there’s nothing I can do about it. But let’s work on this chapter of the book.” Sketching is probably the most solitary part of it, because I don’t even talk to anybody. I do it myself and nobody ever even sees it. The balance of having all of those things — for each of us, depending on our personalities, you have to find the right balance.

Some people just love the craziness of being in a studio, running a studio, having everybody wanting your attention constantly. They thrive on that. For me, a little bit of that — I’m personally happiest if I can balance that with some quiet time, writing time, sketching time, and the smaller projects.

You have your hands on different things at different times. As creative director of a big game, you have your hands mostly on Powerpoint presentations and what you say to people in meetings. You don’t sit down and code. Sometimes if you’re lucky you get to sit down and write a vision document or a little story. If you’re a screenwriter you get to write every word. You have your hands on the script, but then you hand that script to someone. You didn’t make the movie. You made a draft.

Above: Jordan Mechner in 2012.

Markus: If you know the Apple II hardware, you know it doesn’t let you just do what you want to do. The constraints are pretty insane. You have to work with these constraints. It’s different, but–

Mechner: Making the Apple II Prince of Persia, it was like, “Okay, I’ll spend this week making a graphics routine to blast sprites to the screen a little faster than the routine I wrote last month.” That’s what you have to do.

Disclosure: The organizers of Gamelab paid my way to Barcelona. Our coverage remains objective.