Not many people can trace the kind of impact that Katie Scott has had as a game designer at Electronic Arts.

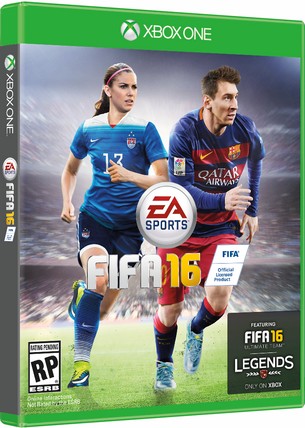

She considered herself a very “typical game designer, an average game designer,” and was working on FIFA, EA’s flagship game played by soccer fans around the world.

But she was passionate about games and about taking the diversity of female characters in FIFA as far as it could go. She helped implement female characters in FIFA. In 2017, she shared a memo about FIFA’s diversity with eight colleagues and bosses. It reached the highest levels of the company, and it spurred changes across all of EA’s games.

If anyone can claim to have struck a blow for diversity at EA, it is Scott. She spoke about her experience at the Gamelab event in Barcelona. I attended her session and recorded what she said. I also asked her some questions, along with other members of the audience.

Here’s an edited transcript of the conversation.

Above: Katie Scott (left) speaks at Gamelab about female characters in soccer games.

Katie Scott: I’m a game designer. I’ve been a game designer at Electronic Arts for about 10 years. The last four and a half years I’ve been on FIFA. I wanted to let everybody know here that I consider myself to be a very typical game designer, an average game designer who designs games. But I happened to find an area of passion for myself within games. I didn’t have any idea that would be a part of my life. I wanted to talk to you a bit about the journey and where we started.

I joined FIFA in 2015 to be the lead technical designer of our story mode, the Journey, which meant my role was mainly in technology. I was tasked with writing a technical pipeline to make cinematics within FIFA, which was something we’d never done before.

When we made the Journey, we thought we wanted to make a story that was diverse. It wasn’t because we had some moral high ground or any business goals in mind. We just thought that football was the most diverse sport on the planet. We had to be true to that, so we put diversity in our game. Our hero, Alex Hunter, is from a biracial family. We gave him a diverse supporting cast with lots of powerful women, including businesswomen. We gave a rich motherly character to the story, an up-and-coming woman player. We were ethnically diverse. Something like 95 percent of our scenes had someone that we considered to be underrepresented in video games.

We said, “Yay, we’re doing amazing. We did such a good job on this. We’re doing great.” But you know, we weren’t doing great. [laughs] In 2017, I guess it was, Electronic Arts invited Julie Anne Crommett. She’s the VP of multicultural engagement at Disney Pixar. She came to EA to do a talk. She talked for maybe 40 minutes. Her message was basically that if you do not know what’s wrong with your product, you can’t fix it. That seems pretty obvious, but I don’t know that it is that obvious.

There was a story she was telling about Grey’s Anatomy. I don’t know if anybody watches that here. Grey’s Anatomy has a woman lead character, a woman hero. It’s directed by a woman as well. And yet when they took a look at Grey’s Anatomy through the lens of diversity and inclusion, they found there wasn’t a single woman background character in an entire season, something like that. It was this crazy blunder. By the time they discovered that, the director was obviously shocked, and she desperately wanted to fix it.

I went back to my desk and thought, “You know, we thought we did a great job on FIFA, but did we? Do we even know? Could we even define the quality of our diversity and inclusion in FIFA?” I was reviewing everything she said and i thought, “How do I quantify this? How do I measure this? How do I say we’re doing a good job on FIFA? What areas of FIFA are we missing on? What is our Grey’s Anatomy character issue on FIFA?”

Above: Four U.S. soccer stars do motion capture for FIFA 16 game.

I decided that I would summarize what I thought were the three critical questions in this endeavor. The first one being, how often do we tell the stories of underrepresented people? The second one is, if we’re putting underrepresented people in our game, how do we make sure they’re portrayed authentically? It’s not enough that they exist. They have to be a positive representation. They have to be real. They have to be someone people can relate to. And the third question being, are we imparting unconscious bias into what we’re doing? Obviously, we’re all susceptible to unconscious bias, and that’s not a bad thing, but it’s something we need to be aware of. If we’re aware of our biases, we can probably smash what they are.

I looked at our story through this, and I thought about these questions. My plan was to look through the entire Journey, every single scene — it was something like 225 minutes of content — and quantify what I was seeing. As much as I thought we were doing okay with women in our game, there were so many areas where we were not doing okay, which was interesting, because I was the lead designer of this mode. [laughs] Clearly I was not doing a good job here.

I detected that many of our women were overly masculine. I also could sense that their art, animation, and areas in that creative department didn’t seem to have the same resources put to them as the male characters did. I also uncovered a couple of really key fixes that we could do right away. This is a video game, not Grey’s Anatomy. I could go to my desk and make changes to our game that day, and they’d show up in the build the next day.

For example, we had a scene in the Journey that took place outside of a women’s match. It was a women’s national team match. And just like in Grey’s Anatomy, not a single woman character in the background. That was a really easy fix. That one we could change — video games have this privilege to be able to change things right away.

Above: Katie Scott spoke on a panel at Gamelab on inclusivity.

But the real results were that I sent this assessment — I called it my diversity assessment for FIFA 17 — to eight people in my company. It didn’t stop with those people. Those people passed it on to other people. People got really excited. People actually rallied around us. Suddenly we sparked a conversation. Everyone was talking about it. My diversity assessment went all the way up to the CEO of our company. Suddenly, on FIFA, we were thinking about diversity and inclusion as part of our process. In the same breath that we’d talk about our budget, our scope, our time, our technology, we would say, “What about diversity? What about inclusion?”

What’s interesting about the questions is that questions are very safe. They’re very non-accusatory. If you’re someone, a developer on a game, and you know a question is coming your way — what did you do to make sure that character was authentic? — that’s in your brain. It plants a seed. It means that the next time you’re going to design a character, you think, “I’m going to be asked that question. I’d better do a bunch of research. I’d better talk to people who are potentially of that demographic to help me with this character.”

What resulted from that was a gaming first, actually. It’s the first female hero in a sports narrative video game. It’s never been done before. That’s Kim Hunter. With her, we used these three questions to completely redefine who she was going to be in this game. We used a couple of women on our team to do script and story consultation, and we did some pretty major rewrites to Kim’s story, because we felt she wasn’t coming through authentically.

I’ll give you an example. In the story Kim is friends with Alex Morgan, who’s a professional player with the U.S. women’s national team. Alex was originally written as a motherly character. We all thought on the team that it would be more appropriate if Alex acted more like a sisterly character to Kim. Kim is really young in the story — she’s 16 years old — and she’d probably think of Alex, someone in her 20s, as more of a sister.

Above: American soccer player Alex Morgan in EA Sports’ FIFA 16 soccer game.

We also gave all-new gameplay mechanics to Kim. We were going to use Alex Hunter, the other hero I mentioned, and his personality mechanics. But we looked at it and they didn’t make sense for her. She was a different person. It wasn’t authentic to Kim. We rewrote that mechanic for Kim to make hers different. We also gave new art, animation, and wardrobe for all the women. By animation, I mean we spent our entire cinematic animation budget on animation for women. We had a massive library of male animations, something like 18,000 clips. Our women’s animation library for cinematics was something like 1,000 clips. It was completely dwarfed. Quite often we would run out of animation and put a male clip on a woman, and you could tell. She’d walk like a cowboy. [laughs]

We ended up with these amazing female characters. We had great female football players. We had an amazing female football coach, who also happens to be LGBTQ, which is part of our story as well. Alex Hunter’s mom is an interesting one. She’s the black woman on the left there. Her story in the Journey is that she’s supposed to be a fashion designer, but in the first Journey, we didn’t pay attention to that particular aspect of her character. We put her in a really ugly green pants suit thing with a horrible hairdo. The actress actually remarked to me that she was really disappointed with the way she looked in the Journey.

And so we went back and saw that we’d missed on this character. What should we do? We didn’t answer that question. What are we doing to portray her authentically? And the answer was nothing. We did nothing. We decided we’d redo her. What does a black woman in her 40s in the U.K. — what might she really be like? We used the actress herself as a source of that inspiration and modeled her entire look after the actress, because she was exactly who we wanted. This is a brand new amazing hairdo, brand new wardrobe, everything. This character is art directed by a woman. She was art directed by a man in the first Journey. There were all these examples of amazing results.

But it got even bigger than that. We used those question on FIFA, but then our company said, “You know what, this is our most important conversation. We want to use this framework on every game at EA if we can do it.” We formed this group called the inclusion council, which is comprised of more than a dozen or so developers at EA, with specialties in diversity or a particular passion for diversity, or people who are part of our employee resource groups for certain groups, including Pride or BEAT, which is the Black American employee resource group, as well as Latinx and people like that.

We now use these questions company-wide. We now have 12 games in the program that we’re assessing through the lens of diversity and inclusion. So many examples of things that we’ve changed — recently the Sims put out a pack that went through the framework and made lots of changes to that. We’ve had so many positive results because of this inclusion framework.

Above: FIFA 16 female player Christine Sinclair

I also want to talk a bit about Volta, which is part of FIFA that we just announced a couple of weeks ago. We’re bringing street football back to FIFA, which has been a big fan request for many years. I’m pleased to say that I was able to completely redesign the character creator for FIFA. I did that with diversity in mind. I wanted to make it easy for everyone to make a character that they could make a relate to very quickly within FIFA.

We also have a couple of FIFA firsts. We have a new create a character that for the first time includes feminine characters, female-identified characters. You can make them now with FIFA. Also a FIFA first, we’re putting mixed gender teams on the pitch. That’s something we’ve never done before. Within Volta you can play together. Finally, we are also serving the story from two different perspectives. If you choose to play as a female-identified character, you get a different story than if you choose to play as a male.

I wanted to share some learnings I’ve had as I’ve gone through this journey. My belief is that anyone can be a hero, yet when I think about what we all might be picturing in our minds when we think about a game hero, I think it’s this. This is an image that comes from Gamer Rant, and they were trying to understand why we believe we need these very grizziled, beardy white dudes to be heroes.

The explanation they come up with is that the non-characterization of heroes is intended to be a blank slate on which you can transplant your own personality. But the problem I have with this is that it makes a very bold and clear statement about what’s normal and default. What it’s basically saying is that being a male of a certain age, of a certain ethnic background, is more normal than something else. I believe we’re staring in the face of an opportunity. I’m mainly going to talk about women here, but I think there are opportunities in many other areas.

First of all, women are just as likely to own consoles as men now. But they’re also 2.3 times more likely to want to play a hero of their own gender. I hypothesize that men are very well-represented in games, and therefore are less likely to feel excluded from gaming. They’re more willing to play as the opposite gender. I don’t know about the women in this room, but when I put in a game and I see an option to play as a woman, I’m like, “Oh, me, there I am.” It makes a difference to me.

Women are a huge gaming segment. I have 45 percent here, but that’s actually the lowest I could find. I’ve seen it as high as 49 to 51 percent. Finally, this is the crazy thing. After all of this amazing stuff that happens, in 2018 at E3 a game was still three times more likely to have a male protagonist in a campaign. That just shocked me.

More stats. 60 percent of girls prefer to play a protagonist of their own gender. Only 39 percent of boys feel the same. The theory here is that it’s stifling sales to girls more than it’s promoting sales to boys, which is interesting, because for 40 years in gaming we’ve thought of boys as the key customer.

And here’s one more thing I want to point out before we move on. It’s extremely healthy to ask men in our society to project themselves onto female characters. When we ask men to see things through the eyes of somebody else, we’re really helping to challenge that idea that men can’t identify with women as full human beings. I believe that we’ll deeply change the way that empathy works in our society if we ask people to see things from a different perspective.

Above: Soccer star Sydney Leroux of the U.S. women’s national soccer team, in EA’s FIFA 16.

Question: I guess this rolled out with Battlefield the last time, and there was a big outcry over it. Could you lay out some of the behind-the-scenes context for that at EA? There was a lot of protest from gamers, that having women soldiers wasn’t really accurate to World War II.

Scott: I can say that — obviously, being on the path to better inclusion at Electronic Arts is going to have its ups and downs. I described in the panel as I don’t expect it to be a leap. We’re here and then we’ll be here. I do expect it to go up and down. With Battlefield, we didn’t have the framework in place. Would things have been different if we did? I have no idea. But I know that going forward, we’re looking forward to doing a better job and making sure that we’re making the right moves for the right reasons. I’m very proud of Battlefield. I’d like to stress that. But I think this is not always going to be easy.

Question: I appreciate the work that goes on inside the game, but I don’t know if the marketing gives the same level of priority to diversity in games. How do you feel about that?

Scott: I mentioned this in the panel as well. I didn’t believe I could work on FIFA. I thought it was impossible that a woman could be on the cover of the game one day. I think in terms of marketing, this is a brand new thing for us, a brand new program, something we just started. We’re starting somewhere, and I really would love to grow the program in so many other ways.

I don’t just mean in character portrayals. I’m interested in accessibility and abled gaming. I’m interested in bringing more diverse developers into the process. There are so many places to take it. So my answer to you would be, I’d love to involve marketing in this as well as we move forward.

Question: When you introduced this change, adding women in FIFA, did you notice an uplift in sales? Do you believe you were able to grow your market, a change in the balance of women and men buying the game?

Scott: When we started on this journey, I really wanted to do this. I thought, “This should be easy. I should be able to get this information no problem. This will be a great metric we can use to measure our success.” It’s actually really difficult to gather that information. Typically people will self-report their gender, and it’s not always accurate. There’s also a lot of questions like, “Why do you want to know that?”

What I found to be interesting is that as time went on — we just didn’t care about that so much. We weren’t looking to boost our sales numbers, or looking to say, “Okay, we have so many million users who are male, now can we add 3 million more if we put women into this game?” I think we were a lot more interested in just doing the right thing, doing the interesting thing, to make our product better. I can’t say that we’ve really revisited that idea since then. Did we need to prove this as a business ROI type of thing? We just kind of left it alone.

Above: Women are on par with men in FIFA 16

Question: I’m interested in how this idea to increase representation was coming from the bottom up, coming from the team, instead of management. How were you able to convince your producers and other superiors that putting more budget and more resources into going in this direction was going to be better for the game, for the audience, for investors, and for the company?

Scott: EA has benefited from the inclusion of several female developers recently on FIFA. Interestingly, when several of us joined, we were aware of each other, but we were also working on something — the art director I mentioned, who art directed Alex’s mother, I didn’t know her at all, but at the same time I was working on some diversity initiatives, she was also working on her boss to say, “We need to do this.” I’d started hearing it from a lot of different angles.

Once you sit down and talk to someone about the reasons why you’d like to do something, it’s actually really easy to get people on board. As much as we believe that diversity leads to better business outcomes, we also have a team of amazing people who are people, who have wives, who have daughters, who have sisters. It wasn’t that difficult of a conversation.

However, we had to do things in certain steps. I came up the first year and I wanted a million things. I couldn’t get all of them, but by the time FIFA 20 comes out — I look back and I can’t believe I got a female character creator in the game that wasn’t there when I first started. I believe that it’s a real testament to the culture we have on FIFA and how much we value each other.

Above: “Oh, no! A g-g-girl! HISSSS!”

Question: The rigging and the technical aspect, can you talk about how much work went into that, or how difficult it was to do the female characters, and why they had to be different from what you’d used for male characters?

Scott: I’m not sure that people are aware of this or how well it’s appreciated, but rigging is one of the most complicated things in a game. So yes, it was a massive undertaking. Again, it’s something that we rolled out over a couple of titles, because it was such a big deal. But if we decide we want to do something, we want to do it right.

Of course there were times where we thought if we could cut a corner here or there, but the answer was always no. We weren’t doing a good job if we were cutting corners. So yes, it was a significant amount of work. But now that we have it, we enjoy it. We can do whatever we want. It’s amazing. I’d say that just in terms of the technical side, the way that women move their hips is the really big thing, and their shoulders. That’s a a really big difference, typically.

Question: I come from the university side. We have women there, but the majority is still men, not only in programming but also in art and game design. As we were discussing before, when we go to high schools and talk to teachers there, it’s usually five men in a room. When I ask they usually say, “Well, we know you came to talk about video games, so we thought you’d want to have people from the technology side here.” And they’re mainly men. I say, “Well, video games are about art. They’re about narrative. They’re about psychology. They’re about all kinds of people.” Never mind thinking that women might be interested in technology. If you don’t have that many women on that side, well, what’s happening?

We have this pedagogical setting where what we see is that it’s underneath our brains. Games are about engineering, and because games are about engineering, that’s supposedly more connected to men. My question, then, is what can I do to attract more women to study games, so that we start reversing the state of things?

Scott: You might be familiar with the story that — when Nintendo brought out their brand new console, the Nintendo Entertainment System, they made the call that stores would put the console in the boys’ toy aisle. That’s set the stage and the tone. Gaming was for males. For a long time, for as much as 35-ish years, gaming actively disinvited women.

We have entire generations of women who didn’t grow up gaming. They find the concept foreign. It’s not part of their hobbies. I’ve worked with women who are hesitant to put their hands on a controller in front of their peers, because they don’t even feel comfortable holding a controller, or know how to use it.

I believe that to really change the course of this — obviously we need women playing games and enjoying games. That will lead to more female developers in general. But at the same time I think we can attack it from another angle. We can change the way that we portray gaming as developers.

It used to be that when you’d go to an interview, people would ask, “Are you a gamer? What games do you play?” We’d like to remove that from our questions. I’d like to remove that from interviews. In fact I’d like to say the opposite. In a lot of the jobs that interviewed for at EA, I say, “You don’t have to be a gamer. I’m not interested in that. I want to know what you’re going to bring to this that’s different.” In fact, I’m happy if you’re not a gamer, because that helps us with something. That maybe helps us understand a big miss that we’ve made.

Above: Female red beret soldier in Battlefield V.

For example, a lot of our quality assurance testers are really huge football fans. When it comes to testing the game from the perspective of being extremely intimate with the game, sometimes they’ll miss something. Sometimes they’ll miss that a tutorial screen has a huge bug in it because they bomb right through it. They already know it so well. I’m interested in people who bring to gaming something that we don’t have already. A lot of the time they’re non-gamers.

We want the best engineers. We want to steal them from Netflix. We want the best artists. We want to steal them from film. We want the best product managers. We want to steal them from hospitals and universities. The only way we can do that is if we tell them, “It doesn’t matter what happened to you in your gaming background in the past, whether it’s there or not. You have a place in games.”

Question: We have a tendency to look at gaming as very endogenous. Everything happens inside the bubble. If you don’t go outside the bubble and reach people outside the bubble, if you don’t draw them in and start learning from them, nothing will happen.

Scott: Consider this. Can you think of an industry that’s more demanding that the people who work in that industry use the product than the gaming industry? I can’t really think of one. Can you imagine if you worked at the Twinkie factory and they demanded that you ate a Twinkie every day to work there? That’s the analogy, right? That’s what I believe about gaming. Anyone can make these. If you’re passionate, if you’re curious, and you’re a problem-solver, there’s a place for you in games.

Question: You talked about the data around how almost 50 percent of gamers in general are women. On FIFA itself, what is that balance like as far online gameplay? We all know that competitive players, especially men, often aren’t so nice when they’re playing online. What do you think Electronic Arts can do to solve that problem?

Scott: Unfortunately, I can’t give exact numbers. That’s sort of our secret information. It is a lot more than you would think. Our female user base is probably a lot higher than the number you might picture in your mind.

As far as your question about toxicity, this is another topic that I think we’re really at the dawn of looking at and trying to take seriously. As a company and as an industry, we’re committed to gaming for all. As we put out more games and see more ways to make sure that gaming is safe — that’s really what it is. I’ve been thinking lately about this idea of safe social. Everyone, or typically a lot of people, want to be social in gaming, but they certainly don’t want to be blasted while they’re doing it. So what are the different ways in which we can help people be safe while they’re being social at the same time?

We’re probably, as an industry, going to have to do a bit of brainstorming and working together and trying to figure this out better. But I’ve seen a couple of different systems lately that get me really excited. Apex Legends has this amazing ping system, where you don’t have to communicate with your party at all, other than in the gaming context. Those are the types of things that really excite me.

I was just at a summit in Los Angeles about three weeks ago with a lot of gaming and social media influencers. We put out the call to them and said, “Hey, you’re a huge part of this. Help us with gaming toxicity. You set the tone. You’re a part of this community. People follow what you do and appreciate what you do. Help us send the message that what we’re looking for is fun and safe gaming. I’d like to understand that better. I’d love to hear what your ideas are.”

Question: Ultimate Team is one of the most popular modes in FIFA. Have you looked at adding women to the Ultimate Team mode? Likewise, are you looking at adding women’s professional teams to FIFA, beyond just national teams?

Scott: That’s a set of questions I actually don’t have a good insight into. We have a whole group of people who do our licensing and deal with the teams you’re talking about. It’s the same with Ultimate Team, because I don’t work on Ultimate Team. I wish I could tell you!

Question: Has there been any discussion about the inclusion of transgender players and characters in FIFA and other games?

Scott: Yes. Obviously — we’re on a journey. We’re starting from something that’s small and trying to grow it There’s a couple of things under the hood that made that difficult this year. It’s something I was interested in for our character creator. But I think going forward we’re always going to be looking for opportunities to be more inclusive, particularly around the the LGBTQ, the transgender space. I believe that’s a demographic in need of authentic and positive representation. I’d love to be able to go in that direction, and I think as a company we would all like to as well.

Question: You mentioned 12 titles that you were working with around this framework. How soon do you think that will be rolling out as part of all of EA’s games?

Scott: We only started this in around February of this year. We thought it was going to be a pilot, that we would pilot this and try it out. But so many game teams came calling. They came to us: “We heard about this inclusion council. How do we get involved in this?” We’re going to start seeing some really positive results, and I believe that what’s going to happen is the game teams are going to come to us, from our studios into our inclusion council.

My dream and my hope is that actually becomes part of our game development framework, which is something that every game team at EA goes through to ship a game. It would be a standard part of our process.

Above: FIFA 16’s “Play Beautiful” ad.

Question: Do you think that men and women are different in terms of gameplay elements and motivation? Do you think that we need to design games differently for men and women?

Scott: I was raised in Canada, in a very diverse country. I think we had something of a simplistic view of diversity in that I was raised to not see color, not see gender. But I don’t think that’s helpful. I think what’s helpful is actually to see people for who they are, because everyone does have a different experience.

Men and women, if we want to make a generalization, do have different experiences. Sometimes they have different desires and different things that motivate them. I think it’s also important to acknowledge that many people are motivated by the same things, whether they’re men or women or of any other gender identification.

I think it’s important to think about game design from a lot of different angles. Should we design games with motivations in mind that women typically have? Yes. Should we design games with motivations in mind that we just think would be interesting, male or female? Absolutely. Should we design games that have motivations that women typically don’t have, but maybe we could pull them in if we look at removing barriers to those different gaming motivations? I don’t think one size fits all. But I do believe that if we can acknowledge both the sameness and differences between different demographics, we’re going to be in a better position.

Question: A lot of people are studying motivation from a game design angle, not looking at gender necessarily, but motivators in general. Richard Bartle was here at Game Lab two or three years ago talking about player types. He developed this concept 20-something years ago. He was the first person to deliver the taxonomy of players. Then we had Amy Jo Kim. She was sort of refurnishing this idea of player types. And then we had Andrzej Marczewski in the U.K., who came up with eight to 12 types.

None of these tie to gender really, but there are people who like to disrupt. There are people who like an entrepreneurial experience. There are people who like to explore. There are people who are pure players, who are just happy playing and don’t care about anything else. What do you think about that idea? It’s growing to a level that looks like consultancy, these metrics that are useful and that we can use like other things. We look at demographics, gender, geography, but we don’t look at motivation as much. Maybe instead of looking at gender, because we have many genders in the end, we should start looking at these metrics of motivation?

Scott: Absolutely. We do use segmentation at EA, what we call segmentation, around different player motivations. There are players who are storytellers, competitive achievers, puzzle-solvers. Those are all different gaming motivations. It’s amazing in that it tells a big part of the story when it comes to game design. But I don’t think it tells the whole story.

For example, you can take a motivation like competitive achievement and you can think, “Okay, as long as the game is really hardcore and competitively balanced, they’re going to have fun.” But they might not have fun because they typically to experience a heart-pounding moment. They love to be competitive, but they also want to get to a point where the game is getting more and more intense and exciting, and then there’s some kind of climax where their heart is beating like crazy. But other people might want to be competitive, but they also want to just relax.

Looking at game design from a lot of these different perspectives is where we’re going to get the best game design. I’m interested in player motivations, but I’m also interested in the types of emotional journeys that people like to be on, the mindsets they enjoy when they’re playing. Just as I’m interested in what people’s gaming experiences are in their lives, what barriers to gaming they face, and how we can reduce those barriers.

Particularly as we’ve been discussing, women have faced barriers to gaming. That means we do have to attend to their specific needs. At the same time, we can be looking at their motivations and their quests for an emotional journey. We have to combine all these things together. I do love the motivation segments, but I think that tells just part of the story.

Disclosure: The organizers of Gamelab paid my way to Barcelona. Our coverage remains objective.