Watch all the Transform 2020 sessions on-demand here.

This morning in a hearing before House lawmakers on Capitol Hill, Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials detailed the administration’s use of facial recognition technologies across the country. It was the second such hearing to date — the first took place in July 2019 — and it followed less than a month after the agency’s decision not to expand screening at airports to all citizens embarking on international flights.

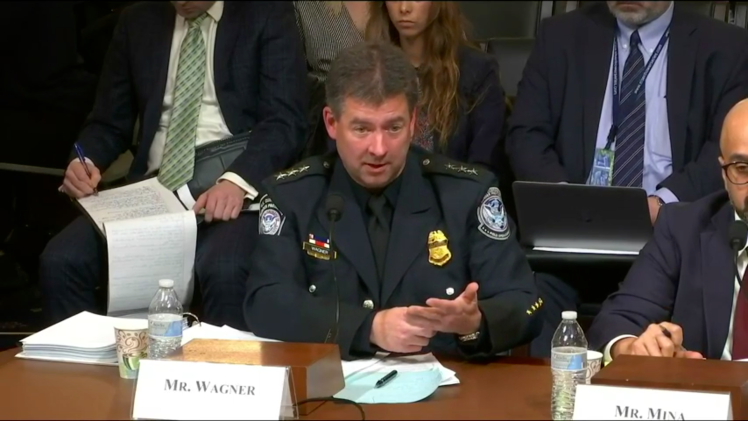

According to John Wagner, deputy executive assistant commissioner at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP), more than 43.7 million people have been scanned by the agency’s Traveler Verification Service and other such systems at border crossings, outbound cruise ships, and elsewhere so far. At undisclosed land borders, it helped to identify 252 people attempting to use a combined 75 U.S. travel documents (like passports and visas) belonging to someone else, about 7% (18) of which were under the age of 18 and 20% (46) of which had criminal records.

“Humans are prone to fatigue. Sometimes, they have biases they may not even realize, including race and gender biases,” he said, demurring on a question about whether facial recognition alone led to the imposters’ identification. “Our officers are very good at identifying behaviors in [a] person when they present a travel document. But the technology on top of those skills and abilities should bring us to the forefront.”

Chairman Bennie G. Thompson (D-MS) countered with a recent study published by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), which attempted to quantify differences for 189 facial recognition algorithms from 99 developers using 18.27 million images of 8.49 million people, the bulk of which were sourced from State Department, DHS, and FBI operational data sets. It found examples of age, gender, and racial bias in several widely deployed systems, to the extent that all but the top-performing systems — a slice of which had no statistical evidence of bias — were 10 to 100 times more likely to misidentify African American, Alaskan Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian American faces compared with their Caucasian counterparts.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Wagner said the CBP uses an algorithm that’s 97% to 98% accurate at matching faces in the DHS’ database — which is expected to have the face, fingerprint, and iris scans of at least 259 million people by 2022 — from one the “highest-performing vendors” identified in the NIST report. (That’s up from the 85% reported by a Homeland Security watchdog in September 2018.) The department is currently using an “early version” of NEC’s facial recognition technology at screening sites, he said, and it plans to switch to a newer version — NEC-3, which had the second-lowest false negative identification rate in a subcategory of the NIST test — as early as March.

In response to a question from Thompson about the algorithm’s accuracy gap — the 2% to 3% percent of people who aren’t identified by CBP — Wagner chalked it up to “operational variables” including camera model, picture quality, lighting, and human behaviors. The quantity of photos of a given person impacts accuracy, too, he said — passport pictures taken when someone was 20 won’t necessarily look like their 29-year-old selves.

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) asked about the CBP’s data storage practices, alluding to a data breach involving the agency’s Biometric Exit program last year. Photos of faces and license plates for more than 100,000 travelers driving in and out of the country were exposed as the result of an attack on a federal subcontractor, reportedly vehicle license plate reader company Perceptics.

Wagner reaffirmed that in the case of U.S. citizens, new photographs captured by the government for purposes of travel documents are discarded after 12 hours (and a potentially smaller window in the future) with “a record of the transaction across the board.” (Information collected from foreign nationals is transferred to a separate database, where it’s kept for 75 years.) And in the event of a recognition error, in-house analysts examine and attempt to correct it — DHS is actively tracking the number of photos it receives and its match rates against them, despite the fact that it doesn’t own all of the equipment used to capture those photos. (Airports and airports like Delta, United, American, and JetBlue operate some cameras in partnership with the DHS.)

Furthermore, Wagner said, airlines and airports are assigned sets of business mandates within which they must commit to refraining from storing, sharing, and saving captured photographs. They’re also required to submit to CBP audits of their cameras and technology, the first of which will take place in the “next couple of months.”

Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-IL) pointed out that some passengers have reported being unaware or confused about how to opt out of biometric screening. Wagner said that to remedy this, CBP is working with airlines to explore printed disclaimers on boarding passes and notifications at ticket booking time and when customers are checking information for other electronic messages. Separately, the agency has taken out some forms of advertising advising people on their options.

“[We’re] answering Congress’ call … by continuing to strengthen biometric efforts,” said Wagner. “Use of facial comparison technology simply automates processes that are often done manually today.”

For more than a decade, Congress has spurred homeland security officials to develop programs that use biometrics to track the movements of foreign nationals existing and entering the U.S. In 2016, lawmakers authorized up to $1 billion from certain visa fees to fund the program, and in March 2017, President Trump signed an executive order to expedite deployment of biometric screening programs.

In December 2019, CBP announced plans to expand screening to as many as 100 million passengers traveling on over 6,300 international flights per week by 2021, including U.S. citizens, ostensibly out of concern that a separate screening process would create logistical challenges. But after pushback from legislators and privacy advocacy advocates, some of whom noted that Congress has never explicitly authorized the collection of biometric data for citizens, it switched course and kept the current system — which allows citizens to opt out of facial recognition screening — in place.