This morning the California Department of Motor Vehicles released a batch of 2019 reports from the companies piloting self-driving vehicles in the state. By law, all companies actively testing autonomous cars on public roads in California are required to disclose the number of miles driven and how often human drivers were forced to take control of their vehicles, otherwise known as a “disengagement.”

Formally, the DMV defines disengagements as “deactivation of the autonomous mode when a failure of the autonomous technology is detected or when the safe operation of the vehicle requires that the autonomous vehicle test driver disengage the autonomous mode and take immediate manual control of the vehicle.” Critics say it leaves wiggle room for companies to withhold information about certain failures, like vehicles running red lights in order to avoid hitting pedestrians about to cross the street. But in lieu of federal rules, the reports offer one of the few metrics for comparing the industry’s pack leaders.

According to the DMV, AV permit holders — of which there are 60 — traveled approximately 2.88 million miles in autonomous mode on California’s public roads during the reporting period, an increase of more than 800,000 miles from the previous reporting cycle. Currently, 64 companies have valid permits to test autonomous vehicles with a safety driver on California public roadways, up from 48 companies in 2018. It’s worth noting that only five companies — Aurora, AutoX, Pony.ai, Waymo, and Zoox — have permits under the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to transport passengers in autonomous vehicles, with Zoox receiving the first one in December 2018.

Waymo

Waymo’s 153 cars and 268 drivers covered 1.45 million miles in California in 2019, eclipsing the company’s 1.2 million miles in 2018, 352,000 miles in 2017, and 635,868 miles in 2016. Indeed, it was a year of mileage milestones for the Alphabet subsidiary, which passed 1,500 monthly active riders in Phoenix, Arizona — the only state of the nine in which Waymo has driven where its commercial taxi service, Waymo One, is available. Waymo announced earlier this year that its autonomous Chrysler Pacificas and Jaguar I-Pace electric SUVs have driven tens of billions of miles through computer simulations and 20 million miles on public roads in 25 cities (up from 10 million a year ago).

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

The company’s disengagement rates dropped from 0.09 per 1,000 self-driven miles (or one per 11,017 miles) to 0.076 per 1,000 self-driven miles (one per 13,219 miles).

The improvements are perhaps partly attributable to Waymo’s AI data mining techniques inspired by Google Photos and Google Search, as well as the company’s ongoing collaboration with Alphabet’s DeepMind on AI techniques inspired by evolutionary biology. DeepMind’s PBT (Population Based Training), which starts with multiple machine learning models and replaces underperforming members with “offspring,” managed to reduce false positives by 24% in pedestrian, bicyclist, and motorcyclist recognition tasks while cutting training time and computational resources in half.

Separately, Waymo says that it’s currently developing its fifth-generation Waymo Driver in Silicon Valley, San Francisco, and Los Angeles and that it runs disengagements through its simulation program. Later this year, it plans to share more on the safety framework it’s developing.

Waymo hasn’t shared the number of customers who’ve ridden in its fleet of over 600 vehicles to date, but it said last December that over 1,500 people are using its ride-hailing service monthly and that it has tripled the number of weekly rides since January 2019. Additionally, it revealed that it has served over 100,000 total rides since launching its rider programs in 2017, and shortly after announcing a partnership with Lyft to deploy 10 cars on the ride-hailing platform in Phoenix, it reiterated that a portion of its self-driving taxis no longer have a safety driver behind the wheel. Completely driverless rides remain available only to a “few hundred” riders in Waymo’s Early Rider program, the company says.

In a move that laid bare Waymo’s ambitions for the lucrative freight transportation industry, the company recently announced it will begin testing Peterbilt trucks retrofitted with its tech stack on “promising” commercial routes in Texas, New Mexico, the San Francisco Bay Area, Michigan, Arizona, Georgia, and on Metro Phoenix freeways (as well as on the I-10 between Phoenix and Tucson). This came after Waymo began mapping the streets of Los Angeles to study congestion and expanded testing to highways in Florida between Orlando, Tampa, Fort Myers, and Miami.

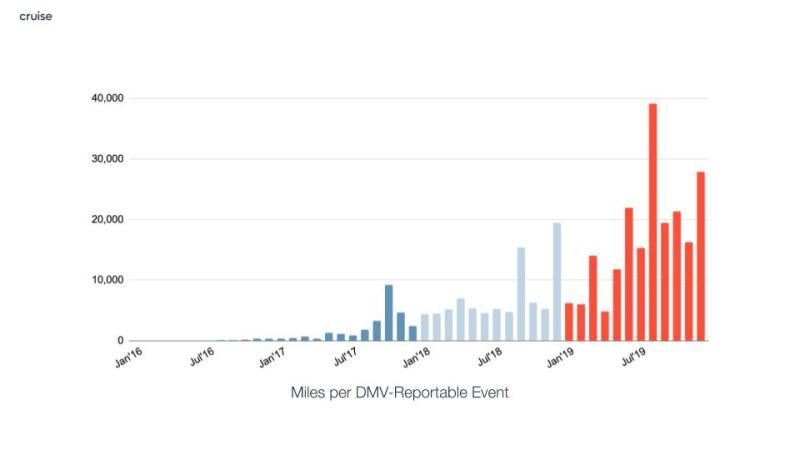

GM Cruise

Cruise Automation, the GM subsidiary that’s estimated to be worth over $14.6 billion, reported a significant uptick in miles driven. Its retrofitted Chevy Bolts racked up 831,040 miles in 2019, up from 447,621 miles in 2018, 131,676 miles in 2017, and 9,776 miles in 2016.

Cruise recorded disengagements for the first half of 2019 separate from those recorded in the second half of 2019, reflecting what it says was a combination of upgrades and revamped testing procedures that drastically cut down on disengagements per mile. In the first half of 2019, Cruise reported 43 disengagements (or 7,635 miles per disengagement) in 328,285 total miles driven. In the second half of 2019, it logged 25 disengagements (or 20,110 miles per disengagement) in 502,755 miles. That works out to 68 total disengagements in 2019, versus 86 disengagements in 2018 (once every 5,205 miles) and 105 disengagements in 2017.

For a frame of reference, that’s across the roughly 233 self-driving vehicles Cruise was operating in California as of early 2019, up from 130 in June 2017.

Cruise CEO Dan Ammann recently offered a glimpse into the progress the company has made toward a fully self-driving vehicle fleet. During GM’s investor day conference in New York, he revealed that Cruise has reduced the amount of time between software updates while cutting the time it takes to train its AI models by 80%. Major new firmware rolls out up to 45 times more frequently than before, and as often as twice weekly.

Cruise runs lots of simulations across its suite of internal tools — about 200,000 hours of compute jobs each day in Google Cloud Platform as of April 2019 — one of which is an end-to-end, three-dimensional Unreal Engine environment that Cruise employees call The Matrix. Over 30,000 instances spin up daily across 300,000 processor cores and 5,000 graphics cards, each of which loops through a single drive’s worth of scenarios and generates 300 terabytes of results.

Cruise operates an employees-only ride-hailing program in San Francisco called Cruise Anywhere that allows those who make it past the waitlist to use an app to get around mapped areas. Separately, building on the progress it has made so far, Cruise has a partnership with DoorDash to pilot food and grocery deliveries in the Bay Area for select customers. The company also continues to make progress toward its Origin vehicle concept, which features automatic doors, rear seat airbags, and other redundant systems and lacks a steering wheel.

Apple

Apple’s ongoing self-driving effort — code-named Project Titan — made incremental regress in 2019, this year’s report shows. Compared with 2018, a year in which Apple’s roughly 52 autonomous vehicles covered 79,745 miles, its 66 cars drove only 7,544 miles in total.

The company’s cars experienced 64 disengagements in 2019, versus last year’s 871.65 disengagements per 1,000 miles with a disengagement approximately every 1.1 mile.

It hasn’t exactly been smooth sailing for Project Titan, which reportedly kicked off as early as 2014. Apple was only permitted to test autonomous vehicles on California roads in 2017, lagging behind rivals like Waymo. And proposed technical collaborations with BMW and Mercedes-Benz failed, as did potential alliances with Nissan, BYD Auto, McClaren, and others.

Eventually, Apple found a partner in Volkswagen, and the two produced an autonomous employee shuttle van based on the automaker’s T6 Transporter commercial platform. But in 2018, Project Titan suffered a blow when a former Apple employee was arrested by the FBI for allegedly stealing trade secrets. In 2019, it suffered another when Apple cut the staff of roughly 5,000 employees by 200, shifting some to machine learning projects.

Shortly afterward, Doug Field, former senior vice president of engineering at Tesla, was tapped to lead the Titan team, and Apple later acquired self-driving startup Drive.ai.

Uber

Uber didn’t report much in the way of progress regarding miles or disengagements in California for 2019, after reporting 2,608 disengagements per 1,000 miles (or 0.4 miles per disengagement) in 2018. In May 2018, the company announced it wouldn’t renew its permit to test self-driving vehicles in California, citing caution in the wake of a fatal accident involving one of its autonomous cars in Arizona.

Above: An autonomous Uber in San Francisco

That’s all likely to change next year. In a bid to close the gap with rivals — including GM’s Cruise Automation and Alphabet’s Waymo — Uber reapplied for a permit, which was granted earlier this month. It cautioned at the time that it didn’t have immediate plans to engage in autonomous driving, although it’s eyeing San Francisco as a potential site. Instead, Uber will kick off driving with trained drivers behind the wheel and notify local, state, and federal stakeholders prior to launching driverless tests.

In an S-1 filing ahead of its initial public offering last year, Uber noted that its Advanced Technologies Group — the division responsible for its autonomous transportation projects — has grown from a team of 40 Pittsburgh-based researchers in 2015 to a 1,000-person workforce spread across offices in San Francisco and elsewhere. Furthermore, Uber said it has collected data from “millions” of autonomous vehicle testing miles to date and completed “tens of thousands” of passenger trips to date. And it’s gathering map data in Washington D.C., San Francisco, Dallas, and Toronto.

Lyft

Lyft’s 20 driverless cars racked up 42,930 miles in 2019 and experienced 1,667 disengagements under the supervision of the company’s Level 5 team — a relatively high number compared with many of its rivals.

The Level 5 team is a group of data scientists, applied researchers, product managers, operations managers, and others working to build a self-driving system for ride-sharing. Since the division was founded in July 2017, the group has developed novel 3D segmentation frameworks, new methods of evaluating energy efficiency in vehicles, and techniques for tracking vehicle movement using crowdsourced maps.

Earlier this year, Lyft announced the opening of a new road test site in Palo Alto, California, near its Level 5 division’s headquarters. At the new center, engineers will mimic real-world driving scenarios involving intersections, traffic lights, roadway merges, pedestrian pathways, and other public road conditions, components of which will be reconfigurable.

Above: A diagram of Lyft’s autonomous car decision-making model.

The development came after a year in which Lyft expanded access to its employee self-driving service in Palo Alto (where it has secured permission from city officials) with human safety drivers on board in a limited area. The company says in 2019 it increased the available routes “threefold” and that it plans to grow the regions covered “rapidly.”

In November, Lyft revealed that it’s now driving 4 times more miles on a quarterly basis than it was six months ago and that it has about 400 employees dedicated to autonomous vehicle technology development globally (up from 300 previously). According to the company, 96% of people who try hailing a driverless vehicle in the Lyft app say they want to do so again.

In May, Lyft partnered with Google parent company Alphabet’s Waymo to enable customers to hail driverless Waymo cars from the Lyft app in Phoenix, and Lyft has an ongoing collaboration with self-driving car startup Aptiv, which makes a small fleet of autonomous vehicles available to Lyft customers in Las Vegas. More recently, Lyft released an open source data set for autonomous vehicle development it said was one of the largest of its kind, with over 55,000 human-labeled 3D annotated frames of traffic agents.

Aurora

Aurora, which last year raised investments from Amazon and others totaling $600 million at a valuation of over $2 billion, reported that its lidar sensor-, radar-, and camera-equipped Lincoln MKZs (which might be swapped out for Chrysler Pacific minivans in the next year) drove 39,729 miles (26,300 manually) and disengaged 10.6 times per 1,000 miles in 2019. (Aurora blames 25% of the 142 reportable disengagements on a software issue that was fixed early in the year.) That record is compared with 11.5 disengagements per 1,000 miles in 2018.

Auora says that after a year of focusing on capabilities such as merging, nudging, and unprotected left-hand turns, its autonomous system — the Aurora Driver, which has been integrated into six different types of vehicles to date, including sedans, SUVs, minivans, commercial vans, and Class 8 freight trucks — can perform each seamlessly “even in dense urban environments.” As it expands its vehicle fleets for data collection, testing, and validation this year, it plans to improve how the Aurora Driver predicts and accounts for “non-compliant actors,” or people who aren’t following the rules of the road, like jaywalkers and drivers who aggressively cut into the lane.

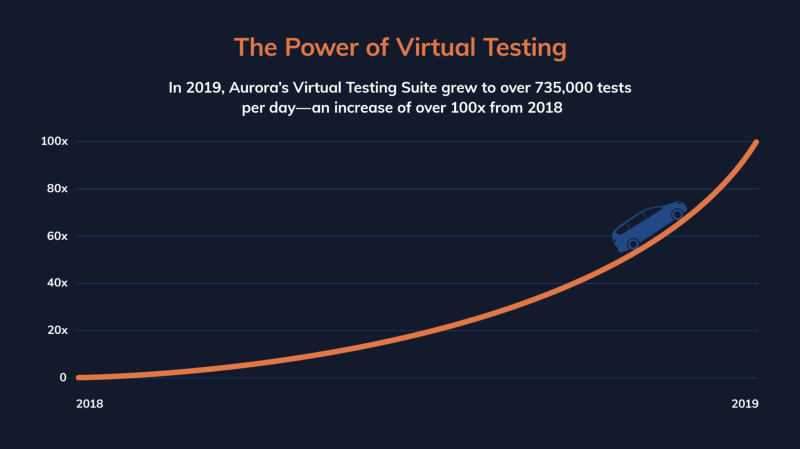

Aurora has prioritized investment in its Virtual Testing Suite, which allows it to run millions of off-road tests a day and feed driving decisions into motion-planning models, allowing them to learn from experience. Thanks to the Virtual Testing Suite, Aurora can model tests involving pedestrians, lane merging, and parked cars. CEO Chris Urmson estimates that a single virtual mile can be just as insightful as 1,000 miles collected on the open road and says that in 2019, virtual testing grew to over 735,000 tests per day, an increase of over 100 times from 2018.

Aurora says that in a typical mile of driving in 2019, its vehicles encountered approximately 3 times more cars on the road and nearly 10 times more pedestrians compared with 2018. Plus, it says the Aurora Driver improved in its ability to nudge (i.e., move around stagnant objects, like double-parked vehicles); navigate pedestrians, crosswalks, and traffic lights; make right-on-red turns onto roads with speed limits no greater than 25 miles per hour; make unprotected left turns that do not involve multiple lanes; conduct lane changes; negotiate merges; and share the road with cyclists, where it slows its speed behind them or merges with them if appropriate.

On the virtual testing side of the equation, the company claims that the Aurora Driver completed 2.27 million unprotected left turns in simulation before attempting to perform one on the road (in September 2019). That number now stands at 31.28 million in simulation.

Nuro

Driverless delivery startup Nuro reported 68,762 total miles driven and 34 disengagements (2,022 miles per disengagement) in 2019, versus 0.97 disengagements per mile (1,028 miles per disengagement) in 2018. It listed 33 vehicles as having collected autonomous miles in California, though it noted that this isn’t the entirety of its fleet.

Nuro was cofounded in 2016 by Dave Ferguson and Jiajun Zhu, both veterans of the secretive Google self-driving car project that eventually spun out as Waymo. The Mountain View, California-based company has about 400 employees and 100 contract workers and has so far deployed over 75 delivery vehicles, and it plans to test 50 vehicles on roads in California, Arizona, and Texas in the coming months, with safety drivers behind the wheel.

In a step toward that goal, the company last week announced that its R2 vehicles had been granted an autonomous vehicle exemption by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (DOT) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

The R2 features a more durable body that’s able to handle a greater variety of roads, climates, and weather conditions than the outgoing R1. Its smooth and rounded cabin, which has contours where side mirrors would otherwise be placed, is designed to create room for bicyclists and other “vulnerable” road users while improving lateral maneuverability.

The R2 will soon join a fleet of self-driving Prius vehicles in Houston, Texas, making deliveries to consumers on public roads from partners including Domino’s, Walmart, and Kroger. Under the terms of the exemption, Nuro will be permitted to produce and deploy no more than 5,000 R2 vehicles during a two-year period, and it will have to report information about the R2’s operation (including the automated driving system) and conduct outreach in communities where it will deliver goods.

Pony.ai

Pony.ai reported that its 22 cars drove 174,845 miles and experienced 27 disengagements in 2019 (6,476 miles per disengagement). In 2018, it said that its cars disengaged 0.98 times per 1,000 miles, or once every 1,022 miles.

The Fremont, California-based startup, which was founded in 2016 by former Baidu chief architect James Peng and Google X veteran Tiancheng Lou, recently concluded a multi-month pilot robo-taxi service in Irvine, California — dubbed BotRide — in partnership with Hyundai (which provided ONA Electric SUVs) and Via (which supplied the passenger booking and assignment logistics). This followed an April test of Pony.ai’s “product-ready” driverless cars in Nansha, China and was one of the first robo-taxi services to be made available in California.

Pony.ai is also collaborating with Toyota to explore “safe” mobility services involving driverless technology across a range of segments and industries. The two companies plan to kick off a pilot program on public Beijing and Shanghai roads to “accelerate the development and deployment” of autonomous vehicles, using Lexus RX vehicles and Pony.ai’s driving system.

Above: A Hyundai KONA Electric SUV outfitted with Pony,ai’s autonomous navigation tech.

Pony.ai’s full-stack hardware platform, PonyAlpha, leverages lidars, radars, and cameras to keep tabs on obstacles up to 200 meters from its self-driving cars. This platform serves as the foundation for the company’s fully autonomous trucks and freight delivery solution, which commenced testing on public roads in April, and it is deployed in test cars within the city limits of Fremont, California and Beijing (in addition to Guangzhou).

Baidu

Tech giant Baidu’s four autonomous cars in California drove 108,300 miles and saw six disengagements in 2019 (a disengagement rate of 0.055 per 1,000 self-driven miles), versus 4.86 disengagements per 1,000 (205 miles per disengagement) the year before. To date, Baidu’s fleet has traversed more than 1.8 million combined miles during tests in 23 Chinese cities, up from roughly 1.2 million miles across 13 cities as of July 2019.

Baidu is slowly but surely progressing toward the launch of a commercial robot-taxi fleet in mainland China. In December, the company announced that it had secured 40 licenses to test driverless cars carrying passengers on designated roads in Beijing, making it one of the first to do so in the Chinese capital. In related news, Baidu inked a strategic partnership with Geely to equip the Hangzhou, China-based automaker’s cars with DuerOS for Apollo, a set of AI-based IoV solutions with voice assistant, augmented reality, and motion detection capabilities.

Above: Baidu and Hongqi: Level 4 car

Baidu is also collaborating with Chinese state-owned car company FAW Group, which develops the Hongqi line of luxury cars, to deploy driverless vehicles in the Hunan capital of Changsha within the next few months. Other automotive partners include Ford, which it embarked on a two-year project to test self-driving vehicles on Chinese roads with.

Baidu separately inked a deal with Volvo to develop autonomous electric cars specifically for the Chinese market. In 2017, it launched a $1.52 billion driving fund — the Apollo Fund — as part of a wider plan to invest in 100 autonomous driving projects over the next three years. Perhaps not coincidentally, Changsha will serve as the pilot site for Apollo Go, Baidu’s ongoing robo-taxi project.

Zoox

The 58 vehicles registered to Zoox, the secretive self-driving car startup headed by former Intel chief strategy officer Aicha Evans, drove 67,015 autonomous miles and recorded 42 disengagements in 2019. That’s compared with 0.52 disengagements per 1,000 miles (or 1,922 miles per disengagement) in 2018.

Like other self-driving vehicles, Zoox’s cars — which have four-wheel steering, dual power train, and dual batteries — use machine learning algorithms to contend with environments they’ve never seen before, like construction zones. They take in visual data and chart new courses around obstructions and obstacles, all without the need for human intervention.

Zoox is testing the bulk of its vehicles in San Francisco (and a few in Las Vegas), like Cruise. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the company is using data collected from the real world to inform simulations that continuously improve its systems’ performance. Its cars drive city blocks to create topologies, and its engineers use these topologies to create three-dimensional representations that AI agents travel endlessly in order to self-improve.

Tesla

Tesla reported a measly 12.2 miles driven autonomously on public roads in California during all of 2019. But the company says it conducts its testing via simulation, in laboratories, on test tracks, and on public roads in various locations around the world, and that it “shadow-tests” its cars’ autonomous capabilities by collecting anonymized data from over 400,000 customer-owned vehicles “during normal driving operations.”

Telsa’s Autopilot — the software layer running atop its custom chips — is effectively an advanced driver assistance system (ADAS) that taps machine learning algorithms and an array of cameras, ultrasonic sensors, and radars to perform self-parking, lane-centering, adaptive cruise control, highway lane-changing, and other feats. The company previously announced that cars with Full Self-Driving Capability, a premium Autopilot package, will someday be ready for “automatic driving on city streets” and to “recognize and respond to traffic lights and stop signs.”

In its most recent voluntary safety report covering Q4 2019, Tesla said it registered one accident for every 3.07 million miles driven in which drivers had Autopilot engaged. According to a model developed by MIT researcher Lex Fridman, Tesla’s cars are estimated to have driven nearly 2 billion miles in autonomous mode,

Disengagements

Whether the disengagement metrics communicate anything meaningful remains the subject of ongoing debate.

Aurora, for one, has noted that disengagement numbers don’t adequately capture improvements or their impact over time. That’s why the company records two types internally: reactionary disengagements, where a vehicle operator disengages the system because they believe an unsafe situation might occur, and policy disengagements, where an operator proactively disengages ahead of an on-road situation the system hasn’t been taught to handle.

Aurora’s Urmson claims that technical or engineering velocity is a superior measure of progress because it captures advancements made on core technology. “Historically, the industry and media have turned to tallying on-road miles and calculating disengagement rates as measurements of progress,” he wrote in a Medium post. “If we drive 100 million miles in a flat, dry area where there are no other vehicles or people, and few intersections, is our ‘disengagement rate’ really comparable to driving 100 miles in a busy and complex city like Pittsburgh.”

In a blog post earlier this year, Kyle Vogt, cofounder and CTO of Cruise, posited that it might be time for a new metric for reporting safety of self-driving cars. “Keep in mind that driving on a well-marked highway or wide, suburban roads is not the same as driving in a chaotic urban environment,” Vogt wrote. “The difference in skill required is just like skiing on green slopes versus double black diamonds.”

Vogt and Urmson aren’t the only ones who have voiced disapproval of disengagement-based safety measures.

San Francisco-based self-driving truck startup Embark, which last year released a voluntary disengagement report, declined to disclose those numbers in favor of a new system of metrics “that [capture] the different scenarios” its system encounters. (Despite this, it revealed that in 2019 it tested 449,837 automated miles with 0 crashes.) “Within the company, we have migrated away from using disengagement rate as a performance metric, and to remain consistent with our internal thinking, we have decided not to release a 2019 disengagement report,” wrote Embark CEO Alex Rodrigues in a Medium post.

Apple has called on the DMV to “amend or clarify” its position on disengagement and testing without safety drivers. And in a blog post this month, Waymo wrote that “the key to self-driving technology safely improving and scaling is through a robust breadth of experience and scenario testing, represented by a wider array of data points beyond disengagement alone.”

“We appreciate what the California DMV was trying to do when creating this requirement, but the disengagement metric does not provide relevant insights into the capabilities of the Waymo Driver or distinguish its performance from others in the self-driving space,” wrote Waymo in a series of tweets today. “While most of the development, learning, and validation of the Waymo Driver comes through billions of miles driven within our simulation environments, our real-world driving experience is primarily outside of California, in markets like Detroit, Los Angeles, and Phoenix. Most of our large-scale real-world driving, which is critical for full-system validation (including validating the realism of our simulator) comes from Phoenix.”

Nuro’s Zhu said in a statement that the metrics for miles driven and miles driven per disengagement are “not a comprehensive measure” for technological success, business maturity, or safety. “We view the autonomous vehicle disengagement reports as an opportunity to amplify the comprehensive safety strategies used by Nuro to develop our autonomous technology,” he continued. “We also continue our engagement with regulators on how our unique vehicle design and operation prioritizes the safety of others with whom we share the roads.”

In a conversation with VentureBeat, Dmitry Polishchuk, the head of Russian tech giant Yandex’s autonomous car project, noted that Yandex hasn’t released a disengagement report to date for this reason. “We have kind of been waiting for some sort of industry standard,” he said. “Self-driving companies aren’t following the exact same protocols for things. [For example, there might be a] disengagement because there’s something blocking the right lane or a car in the right lane, and [the safety driver realizes] as a human that [this object or car] isn’t going to move.”

Stalled regulation and skepticism

Unfortunately for companies like Yandex, Cruise, and Aurora, autonomous car companies can likely expect less regulatory guidance, at least in the U.S. At CES on January 8, Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao announced Automated Vehicles 4.0 (AV 4.0), new guidelines regarding self-driving cars that seek to promote “voluntary consensus standards” among autonomous vehicle developers. The guidelines request but don’t mandate regular assessments of self-driving vehicle safety, and they permit those assessments to be completed by automakers themselves, as opposed to by a standards body.

Advocacy groups — including the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety — almost immediately criticized the policy for its vagueness. “Without strong leadership and regulations … [autonomous vehicle] manufacturers can and will continue to introduce extremely complex supercomputers-on-wheels onto public roads … with meager government oversight,” Advocates president Cathy Chase said in a statement. “Voluntary guidelines are completely unenforceable, will not result in adequate performance standards, and fall well short of the safeguards that are necessary to protect the public.”

In the U.S., legislation remains stalled at the federal level. More than a year ago, the House unanimously passed the SELF DRIVE Act, which would create a regulatory framework for autonomous vehicles. But it has yet to be taken up by the Senate, which in 2018 tabled a separate bill, the AV START Act, that made its way through committee in November 2017.

There’s evidence to suggest the standstill is contributing to public fears about self-driving cars. J.D. Power’s inaugural 2019 Mobility Confidence Index Study found that a majority of respondents harbor doubts about the technology’s robustness, with 71% saying that they’re worried about driverless system failures or errors and 57% saying they fear malicious vehicle hacks. This was roughly in line with results from a PSB Research survey commissioned by Intel last year, which indicated that nearly half (43%) of people don’t feel safe around driverless vehicles, and a recent CarGuru survey of 1,146 automobile owners that found that 87% wouldn’t rely on autonomous cars given the choice.