To brand or not to brand is one of the oldest discussions in video games. Adding a popular brand like Harry Potter could be just the thing for Niantic’s next game, coming on the heels of Pokémon Go. But Electronic Arts once focused a huge amount of resources on brands like James Bond and Harry Potter, and it encountered oversaturation and consumer exhaustion.

We discussed these topics at a panel I moderated at the recent Montreal International Game Summit. Brands in games are cyclical. Sometimes they work in the early stage of a platform, and sometimes they do better amid an explosion of titles, like with the mobile game ecosystem.

We knew this is well-worn territory, so we tried to make the session as in-depth as we could. We looked at the pros and cons of brands versus new intellectual properties across many different franchises. My expert panelists included Caglar Eger, head of strategic partnerships at Goodgame Studios; Matthew Leopold, director of global business development at Yodo1; and Louis-René Auclair, cofounder of RocketJump Games and former chief marketing officer at Hibernum Creations.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: Brand panel at MIGS 2017: (left to right) Caglar Eger of Goodgame Studios, Matthew Leopold of Yodo1, and Louis-René Auclair of RocketJump Games.

Caglar Eger: I work at Goodgame Studios, which recently merged with the Stillfront Group. Now we’re a listed company in Sweden. We’re about 250 people, based in Hamburg. We’ve been developing games since 2009. We jumped into mobile games, originally coming from web games, in 2013. Our best known game is Empire: Four Kingdoms on both web and mobile. The franchise generated more than $800 million in the last five years. I’ve been doing business development for Goodgame Studios since 2012.

Matthew Leopold: I head up Yodo1’s business development and marketing team. Yodo1 is a Chinese publisher. We recently moved into the global spotlight with a couple of titles called Crossy Road and Rodeo Stampede on the mobile side. We’ve also started publishing on the PC in China, working with a bunch of developers from all over the world. We were founded in 2011 and we’ve been bringing games to the Chinese market ever since. I’ve been working in China for the past six years. I just moved back to the states a month ago. It’s still pretty new to me.

Louis-René Auclair: I head RocketJump Games in Montreal. I used to be the chief marketing or business or branding officer at Hibernum here in Montreal as well. Unfortunately they closed down last summer. I’ve been working with IP almost all my career, in video games and toys, most recently with Beauty and the Beast and the Bruce Lee IP as well.

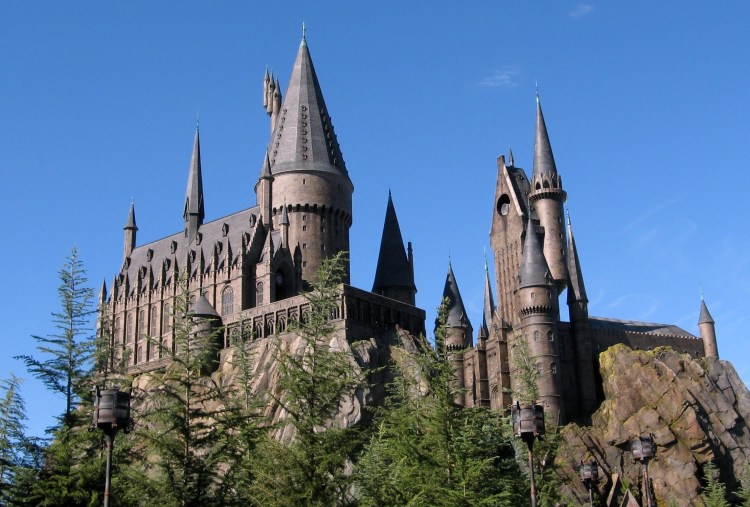

GamesBeat: One good thing to start with is, what is a brand? I wrote about Jam City, a mobile game publisher. They announced that they’re making a Harry Potter game. The Harry Potter brand has a lot behind it. It has 450 million books sold and $7.7 billion generated by the films. You can figure that’s pretty well imprinted on billions of people around the world. That’s a brand.

A lot of indie developers start out thinking they’ll make their own brand. There’s a scale issue around how you get started with a brand and where you can go with it. How would you tackle the subject?

Auclair: Creating a brand or using a brand comes down to what your goal is with your game, with whatever you’re creating. Obviously using an already existing brand costs you money. That money should go toward getting more users for your game. Hopefully using a brand generates more downloads. So then you have to do the math and evaluate. If I create my own brand, how much marketing do I have to spend to get people notice my IP and make it a well-known brand?

We talk about Harry Potter being a brand. Yes, it generates billions of dollars, but it also cost billions of dollars to make the movies, to make this brand. There’s a lot of money involved on all fronts. If you don’t have the ability to spend up front, to create your brand and get eyeballs on it, you should go with an existing IP. But the IP is going to cost you money. It’s all about, I believe, your own creativity and your own focus, how you want to approach your game and your IP.

Leopold: It’s important to consider where the brand is in terms of geography and what you’re going for in terms of marketing. Some brands, like Marvel, do very well universally, but some brands don’t exist in China. A lot of the Fox brands don’t make it in China. You have to think about the markets you’re targeting with a brand. A brand is only considered a brand if it’s known in the region you’re going for.

Eger: The main question for game developers—do you need a brand to create a successful game? This is something that’s becoming, these days, pretty common. People are using existing IP, whether it’s big or small. It doesn’t matter, so long as there’s an IP, because the hope is to reduce your marketing cost. Three or four years ago, you had a CPI cost of 50 to 80 cents. Now you’re paying $15-20. That’s one of the biggest reasons game developers are moving to IP. The question, again, is do you need to do this to have a successful game?

Above: James Bond

GamesBeat: So the point of advertising is to get people familiar with your brand, but if they already know the brand, that’s a step that’s out of the way for you. You can just start selling.

Electronic Arts used to be nothing but Hollywood brands. They had James Bond. They had great success with Harry Potter. And then at some point they hit a wall. These brands in games stopped resonating with people. Why did that happen? Harry Potter is as strong today as it ever was, generally, but at some point EA gave up making Harry Potter games. Why not make one every year?

Eger: I think that’s something EA needs to answer. [laughs] But is overexposure a problem? You look at Marvel, for instance. There are so many Marvel games these days. What is a brand’s value if you create a new game alongside so many other people using that same IP? This is something you need to ask yourself.

Besides that, some developers also think—this is maybe something EA recognized. You don’t need an IP to make a good game. If you have an IP, you won’t automatically have a successful game. You need a great game first, and then maybe you can put an IP on it if you think that will lower your CPI costs. But nothing else works if you have a bad game.

Auclair: Yeah, I think EA fell victim to the brand-slapping strategy. People were seeing a lot of success, other studios started doing IP games as well, and they did what we call “brand slaps.” Take a brand and put it on the box, even if it doesn’t have anything to do with the lore of the IP.

It’s about treatment. It’s about the maturity of game-makers and the maturity of the public. At some point you get sophisticated enough to go looking for better entertainment, better games, better gameplay. If you buy a game about King Kong and it doesn’t do anything with the brand, doesn’t explore that world, doesn’t deepen your love for the world, it’s useless. It’s a bad strategy to take IP and just make crap with it, and that’s what happened on the console front. To this day it’s difficult to get good console games from Hollywood.

In mobile, because of the cost of user acquisition and marketing in free-to-play, it’s still pretty relevant. But you see that the games coming out are much more sophisticated. They use the brand properly. They promote the brand.