There’s no question that Apple’s design chief Jony Ive is leaving the company with a complicated legacy — too many elegant hardware designs and patent-worthy enabling innovations to count, offset by some profoundly misguided software interface decisions and an irritating track record of fragile products. It is now impossible to consider Apple’s triumphantly thin MacBook laptops without worrying about the longevity of their keyboards or whether their screens may stop working due to overly thin cables; similarly, even Apple’s latest operating system releases still bear UI design scars from Ive’s infamously shoddy redesign of iOS 7 six years ago.

I have loved many if not most of the products Apple has released over Ive’s tenure, and even though I was one of the first (if not the first) to publicly call him out nine years ago for violating several of famed designer Dieter Rams’ principles of good design, there are few designers I admire more than Ive. His work brought me back to Apple’s Macs after years in the Windows PC wilderness, introduced me to the best music players, phones, and tablets I’ve ever owned, and even convinced me to give wristwatches another try. I live with, rely upon, and appreciate his work every day.

But that doesn’t mean I’m blind to what has happened with Apple’s design during his tenure, particularly over the past decade or so. One of my chief complaints nine years ago was that, antithetical to Dieter Rams’ principles that good design is long-lasting and environmentally friendly, Ive was increasingly creating products that were easily damaged and destined to be tossed out rather than repaired. The iPhone 4 — a memorably beautiful device — was just the first in a series of Apple smartphones that even the company’s hand-picked reviewers accidentally shattered during early testing. Several earlier iPods were so easily scratched that the company faced class-action lawsuits over unusably tarnished screens, to say nothing of their instantly scratched mirrored backs.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

This is a design issue, but it’s one dictated by business decisions — Tim Cook’s department. Sure, I can understand the business logic behind making beautiful things that quickly begin to degrade in either appearance or functionality. The theory is that an initially satisfied customer will blame herself for the product’s eventual failings and return to the store to purchase a replacement. In practice, this theory is certainly true for some people, but generally only for a limited period of time. After it happens twice, or under questionable circumstances — did I breathe on it wrong? Is the software update actually slowing my device down? — the person begins to wonder what’s actually going on. And at some point, the jig is up.

Apple has maintained that there’s nothing seedy going on — that it is a world-leading recycler, and thoughtful about keeping devices running for years — but the reality isn’t that simple. Years after the first glass-bodied iPhone, which was followed by multiple metal-bodied sequels, it’s gone back to selling glass devices again. It might be the strongest or most recyclable glass Apple has ever used, but the glass still shatters after accidental drops and costs hundreds of dollars to replace. And regardless of whether it calls this “recycling,” its retail employees still push users to consider replacing their old devices rather than fixing them.

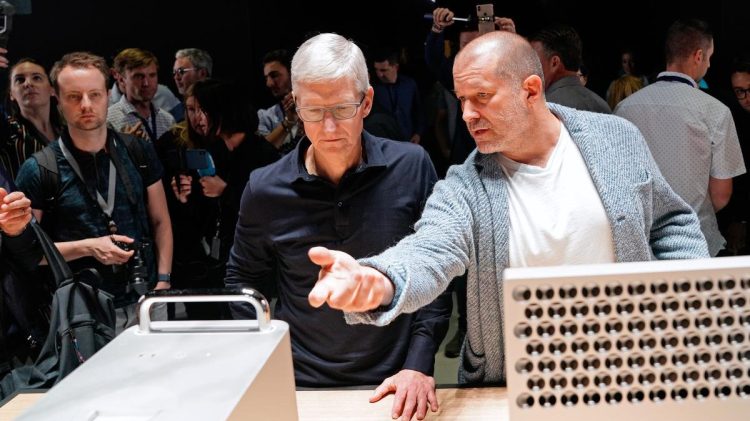

You can debate whether this is actually Steve Jobs’ legacy, Jony Ive’s, or Tim Cook’s, but it’s one of the most glaring problems with today’s Apple, and is long overdue to be fixed. Any environmental report is incomplete without mentioning that hundreds of millions of new devices are being manufactured in a manner that makes them highly likely to require repair or replacement within several years of purchase. More than anything else, remedying this should be Apple’s biggest post-Ive design pursuit.

Will making more durable products compromise unit sales? Perhaps, but Apple doesn’t report unit sales anymore anyway. And as I’ve said before, even unit sales needn’t suffer if the company returns to its prior practice of offering devices at every market price point, rather than just midrange and high-end ones. Since less expensive products tend to sell at multiples of more expensive ones, whatever replacement shortfall the company might suffer with existing customers can be more than made up for by attracting new ones.

![]()

As important as hardware has been to Apple’s success, its software user interfaces have struggled ever since UI design was added to Ive’s responsibilities years ago. Ive took the reins from departing SVP Scott Forstall, a Steve Jobs protege who famously obsessed over individual app icon pixels with the same sharp lens as his boss, and agreed that skeuomorphic design — using real-world textures and objects in digital interfaces — was intuitive for users. Under Forstall, Apple’s UIs didn’t put a button labeled “Back” on the screen when a backward-pointing arrow sufficed, and the arrow didn’t have to look plain when a nicer one could match the rest of the UI.

Ive tossed that entire philosophy and much of Apple’s prior iconography out the window when he redesigned iOS 7, suggesting at the time that users had grown past the need for visual metaphors and would benefit from cleaner, simpler interfaces. Drop shadows were dropped, anything detailed was flattened, and everything from text to glyphs (including arrows) became illegibly thin. It was embarrassing, and the immediate result was an interface that looked like an ugly cartoon, without any of the nuances that had made iOS the envy of the mobile device world.

Apple’s retreat from skeuomorphism was at least partially backed at the time by the usual coterie of Apple Kool-Aid drinkers, but it was a mistake that the company has continued to claw back from every year since it happened. Ever since iOS 8, the refrain each year has been that iOS 7’s rough edges are getting polished, but overall, both the operating system and its third-party apps have lost all of their personality — unless you count emojis and Animojis, there’s nothing fun or charming about Apple’s software anymore. Even the very latest iOS 13 betas feel drab compared with pre-iOS 7 UIs, while the continued use of flat, shadowless UI graphics makes poor use of the devices’ high-color, high-resolution screens.

Ive might or might not have been responsible for all of the bad UI decisions, but as with Apple’s hardware, his departure gives Apple the perfect opportunity to substantially change course rather than make small adjustments. Apple had its “aqua” and “brushed metal” phases, the former rather famously drawing customers back to the Mac after a period of stagnation. Moving past “flat” to something better — preferably with enough shadowing to promote legibility — would be a very welcome next step.

Over the past six months, it’s become clear that Apple is hoping to make more money on services than ever before, which is to say that it won’t rely as heavily on growing hardware or software sales to keep growing its revenues. To sell services, however, it will need not only to keep existing customers buying more Apple products, but also to win over new customers, tasks that will only be accomplished if its hardware feels worthy of a premium and its software remains atypically easy to use. As competitors are coming closer than ever to closing the gaps on design and user experience, improving hardware durability and software UIs are solutions that are well within Apple’s abilities. Only time will tell whether it has the courage to make the big changes here that will ultimately benefit its customers.