Watch all the Transform 2020 sessions on-demand here.

All machines built prior to the computer were designed to serve as an extension of the human body. Think of things like the crane, the bicycle, and the butter churner. The computer was the first machine built to expand the human mind. The interface has changed over the years, but the goal has remained the same: to develop a machine that can perform intellectual tasks better than a human, just as a forklift lifts objects better than human arms do.

To date, we have not built a machine that can perform every single function of the body at once, and we also have yet to develop a form of artificial intelligence that can effectively do all that a human brain can. And yet much of the rhetoric surrounding chatbots is monolithic, assuming that they are useless unless they can speak and think as well as a human can. This is a mistake.

No single chatbot can perform every mental function we want from it. Though some have tried — think: Alexa and Google Assistant — none have succeeded. And this should come as no surprise; after all, we have yet to create a machine that can both shovel a hole and beat an egg. Instead, we have opted for an army of machines, each of which has a narrow purpose that it performs far better than its human counterpart ever could.

The chatbot market has already begun to fracture and narrow. WeChat, for instance, offers two bots: subscription accounts bots and service accounts bots. The first bot’s purpose is to discover. It understands a wide vocabulary using natural language processing (NLP) and helps users search for and discover content, much like Google does. The second bot, which we’ve termed the service bot, has existed since the 1960s and is designed to follow a simple decision tree structure. This chatbot is highly functional today, and serves a purpose in many areas including airline ticket reservation, ordering food at an airport restaurant, customer service, and checking in at a doctor’s office, just to name a few.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Both types of bots can be highly functional; the problems arise when we expect one to do the work of the other. In fact, WeChat developed this market split after rolling back more intelligent versions of these bots based on user dissatisfaction. The reality is that users don’t want AI-driven, chatty, Turing-test passing bots. They want bots that will effectively facilitate the completion of a goal.

The discovery bot

The discovery bot attempts to tease out intent based on natural language processing, much in the same way that the Google algorithm identifies a searcher’s goal. Unlike traditional search bars, however, the discovery bot offers a mobile-friendly way of setting parameters around your search.

For instance, if you were to turn to your personal shopper bot and say that you want a pair of winter boots, the bot would extract intent by setting parameters around what you want. It could ask, “Are you looking for ankle boots or knee-high boots?” or “Would you prefer leather boots or man-made materials?” The way we currently set these limits is highly manual: We choose from a drop-menu or type parameters into a search bar. The discovery bot instead limits the options it shows based on a series of questions and answers.

The most revolutionary aspect of this bot is that it learns your tastes over time. The results it shows you eventually become highly tailored to your preferences. This is the opposite approach to search that, for instance, Amazon.com uses, where it shows the most highly rated or the most popular items on the first page, but includes all 480 million items that it sells. The user then has to narrow which items they are shown through drop-down menus. Chatbots move us away from this crowd-sourced model of search to a personalized model.

Alibaba, the Chinese ecommerce giant, has deployed a chatbot named AliMe that identifies intent, matches queries with answers based on a knowledge graph, and then offers personalized shopping help. That said, the bot’s natural language processing is imperfect, in part because users themselves may not express semantic intent accurately. Furthermore, users often modify or completely alter intent midway through a shopping experience, which can derail a logic-loving bot.

Another potential problem with discovery bots — and the reason that we have not yet seen them widely deployed beyond individual brands — is that when chatbots learn through machine learning without any direct human control, they can learn the wrong behaviors. This is what happened with BabyQ. While machine learning provides the best framework for bots to learn, it also separates the bot’s internal logic from the developer perspective and makes it harder to control.

Because of this, the most effective discovery bots today are brand associated and follow a decision-tree structure. If the bot’s conversational abilities are controlled and restricted, then it certainly won’t turn into an expletive-loving racist; the downside is that such a bot reads as less human and conversational.

The service bot

The service bot’s purpose is to fulfill simple tasks, gather feedback, and provide customer service. This bot is significantly easier to build than the discovery bot because its user’s intent is not open-ended. Because it doesn’t need to process language and parse the user’s objective, it can just lead the user through predetermined decision tree paths.

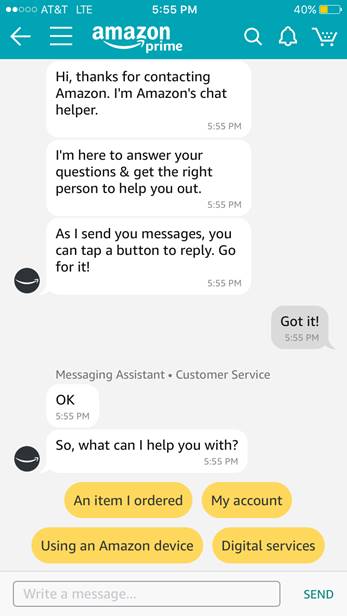

The service bot is significantly easier to deploy and also significantly more user-friendly. As the screenshot above shows (taken from the Amazon Prime customer service chat option), the chatbot is essentially just presenting menu options that lead users down different paths to support. This mitigates the chances of the chatbot misunderstanding its interlocutor and eradicates the need for the machine to identify intent — the users do so themselves.

Companies already deploy these bots in a variety of fields. From the Domino’s Facebook bot to the Marriott Slackbot to the Amazon Customer Service Bot, many businesses are putting chatbot technology to use to streamline operations. By leading customers through a mobile-friendly series of choices, the chatbot is able to rapidly meet customer needs, whether it’s troubleshooting an Alexa-enabled device or ordering a pizza. Most of these bots also have a minimal level of NLP. For instance, the Domino’s bot understands if you ask for the day’s deals, even though those aren’t included in its menu options. But these bots are not designed to stray too far from their limited initial offerings.

These bots are ideal for interactions that have a restricted number of paths the user can take. Note that there are only four initial paths you can go down with the Amazon bot. By stating up front what they can do, the bots also set up expectations for their capabilities. The Amazon chatbot doesn’t help you pick out a bridesmaid’s dress, nor would you expect it to.

It’s about interface, not intelligence

Both the discovery bot and the transactional bot are useful to the user because of their respective interfaces. While they both do have elements of artificial intelligence, their purpose is not to pass the Turing test, but to make online interactions easier and more personalized on the mobile screen. And when businesses leverage this advantage, they will see that introducing chatbots to their online processes can dramatically improve the user experience.

The pitfall of chatbots thus far has simply been that we expect a single bot to perform the acts of many. We have made the chatbot in our own image. But the chatbot is still a simpler species than we are, and for now, it offers the most use via narrow, streamlined settings.

In fact, this mirrors evolutionary development. Complex nervous systems take millennia to develop, while simpler parts of the body, like kidneys, existed in animals long before higher consciousness did. But to throw the baby out with the bathwater would be a mistake. Instead, we need to use the simpler organs that the chatbot currently possesses, and give it time and training to develop complex systems like accurately identifying open-ended intent and learning to mimic human speech. Conversational interfaces like those in movies such as Her come to mind as a perfect example, ostensibly evolved out of simpler versions of themselves.

Luckily for us, human developers act much more rapidly than Mother Nature. Companies will likely develop the discovery bot in various retail settings this year (pioneers including H&M and Sephora have already launched versions of it), and in the coming 10 years we may even begin to see these distinct breeds evolve into one highly intelligent chatbot that can actually hold a human conversation.

Abinash Tripathy is the CEO and cofounder of Helpshift, a customer support platform.