At sites around the world from Tokyo to Los Angeles, Berlin to Paris, London to New York, locations are becoming new places to perceive our everyday surroundings differently via mobile phone-based augmented reality. Personal computing is migrating from the one way 2D screen to the mobile camera lens/3D view, promptly changing the rules of UX/UI design. Where will you anchor digital content? What are you going to make your users feel? How does the AR designer respond?

All the world’s a stage

Architectural, product, or current UX design methodologies alone are not enough to deliver great AR immersive experiences. AR immersive experiences are a type of storytelling were design should strive to serve the story, whether the work of a single visionary writer or the local social stories of the individual. The reason, in part, Samuel Beckett and Henrik Ibsen are among the most influential theater innovators of the last two centuries was their monastic attention to design.

For designers aiming to create great experiences, there is a design history that can inform their work despite having to experiment in a new medium. “Seeing place,” is the source etymology of the word “theater” stemming from the ancient Greek “theatron,” and it is theater design that offers seven practical insights for AR design.

1. Define the mise-en-scène

“Mise-en-scène” refers to “everything placed on the stage or in front of the camera — including people. In other words, mise en scène is a catch-all for everything that contributes to the visual presentation and overall look of a production. When translated from French, it means ‘placing on stage.'” Acknowledging the size, shape, and layout of an indoor/outdoor space directs a performance’s mise-en-scène, ultimately the design aspect of theater production. It is the visual theme or telling of a story.

On entering a theater of any kind, a spectator walks into a specific space, one that is designed to produce a particular reaction or series of responses, the reception of that space becomes part of the total theatrical experience. What will the AR experience provoke?

2. Use proxemics

The Apple AR(t) initiative is a guided walk within six cities which includes iPhone-based AR experiences by six artists including Nick Cave, Cao Fei, and John Giorno. Similar to a scenographer (theater designer), as part of this design process the artists would have to apply the study of proxemics — how humans use space when we are communicating, the manipulation of space and spatial relationships among people, (digital) objects, and setting/location.

Where to anchor content? What scale should the digital content be at this location? How should this make the user feel? By answering such design questions, combining unique location, digital content, and storytelling, AR experiences can avoid becoming stagnant and billboard-like.

3. Use composition

The pleasing arrangement of actors/digital content within the theater ground plan/map of the location for the AR experience that lets the audience/users know where to look at a given moment. Drafting a ground plan indicates the proxemic potential of the actors/digital content and the theater space. The purpose is to discover dramatic actions and to illustrate these in the simplest possible way through emphasis or contrast. Composition does not require movement at all, it is a static caught movement in time and space, leading the audience to see what the director/AR UX designer believes is essential. It concerns itself with clarity like a still life painting of the stage at one moment in time.

4. Use blocking

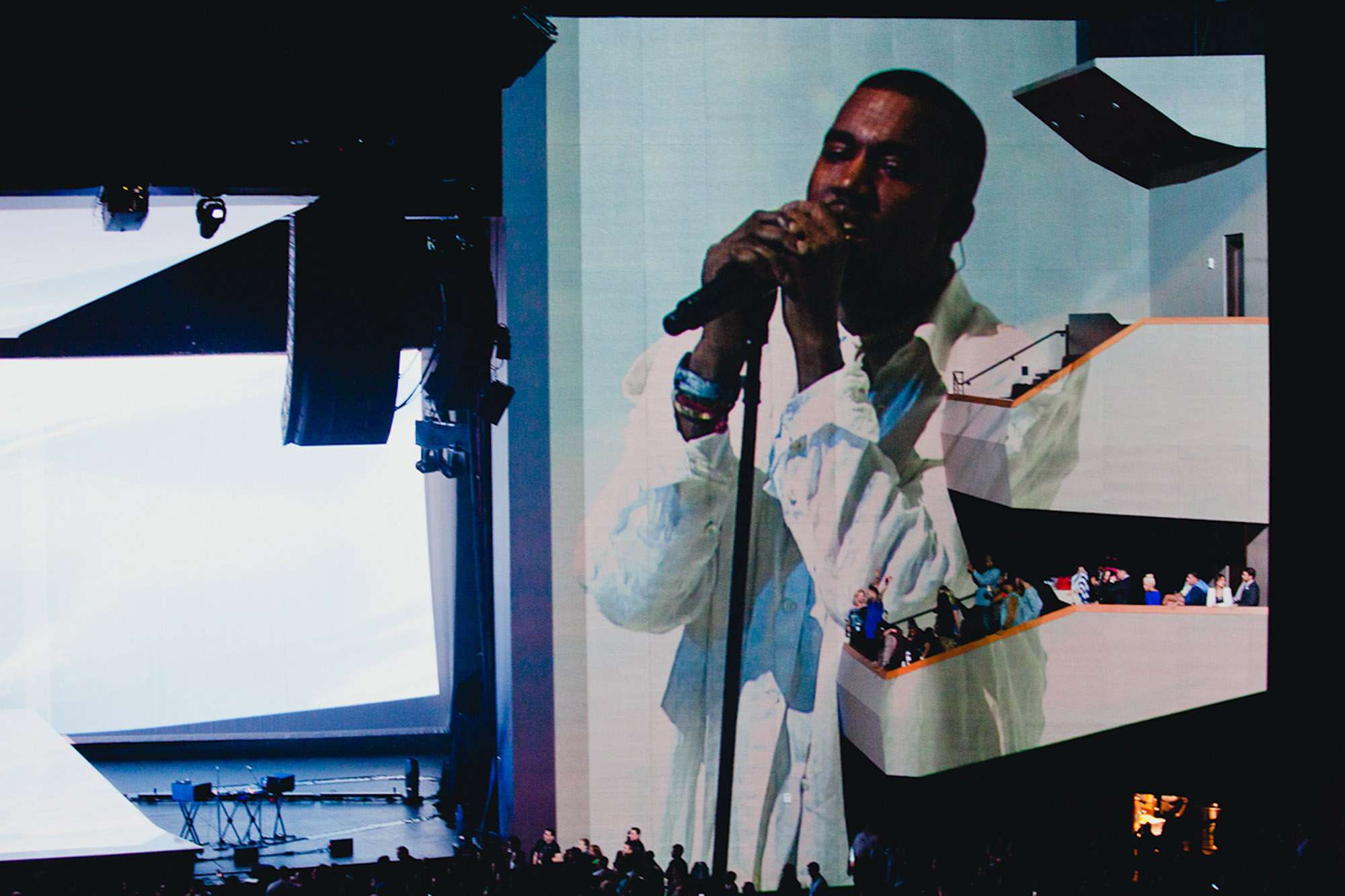

“The theater demands democracy for the same experience from every angle,” notes stage designer Es Delvin, whose clients include Kanye West, U2, and the Royal Opera House, and it is blocking, the choreography of the play/AR experience which promotes such. It is clarifying the movement of the actors/digital content or users and the unique relationships of the characters. The physical distance between people can relate to social, cultural, and environmental factors, even stressing character and plot development. Something as simple as strategic placement, lighting, and controls can make an emotional impact for the user.

Above: Es Delvin’s AR for Kanye West

5. Use picturization

A process by which we add meaning, the storytelling aspect of blocking. The stage designer Minglu Wang asserts, “I am not only designing what the audience can see on stage but also the empty space that they can’t see.” Picturization tries to get across subtext — the meaning that may not be supported by the words. It is the visual interpretation of each movement at play so that the dramatic nature of the situation will be covered to the audience / users without the use of dialogue and action. It allows the designer to explore and discover. In Japanese theater, “Mie” or “frozen moment” is a powerful and emotional pose struck by an actor who then freezes for a moment. It is meant to show a character’s emotions at their peak, one that remains in the mind of the viewer.

6. Collaborate within a vision

The AR Designer is a leader of collaborators working towards a sole vision similar to a scenographer, who is responsible for all of the aesthetics of a performance. In a recent project supported by Google and architect David Adjaye at the Serpentine Gallery, Hyde Park, London, artist Jakob Kudsk Steensen was required to lead a diverse team to realize his AR application with the collaborators comprising a technical director, curator, producer, developers (inclduing Unreal developers), UI & graphic designers, field recordist, sound designer, audio developer, researcher, narrator, and subject matter experts from the British Natural History Museum.

7. Design for the human locale

What does theater do? According to Ariane Mnouchkine, Ibsen theater award winner and cofounder of the Théâtre du Soleil, “theater is a ritual, one should go out of the theater stronger and more human than when you went in … epic theater is where the audience shares a moment of consciousness.” In Berlin, the MauAr app enables visitors to see how the Berlin Wall changed and grew over the years before coming down in 1989. One of the aims of the app creator was to “understand what it was like to live in a dictatorship and then in turn what it is like not to live in a dictatorship, and how valuable freedom, democracy, and human rights are.”

Here’s to the storytellers

The 2018 staging of “The Encounter” at the London Barbican by Simon McBurney was minimalist with sound being deployed to aurally immerse the audience in the play’s setting, the Amazon jungle. It exemplifies how spatial design means not simply designing the space on the stage, but the space inside the audience’s heads. Es Delvin remarks, “theater-makers are aware of the ephemerality of what they’re making. In the end, everything is only going to exist in the memories of people.”

With the nascent mobile technology of AR, the creation of imaginary theatrical worlds wholly independent of temporal and spatial constraints of the physical world is steadily becoming quite possible. As the script of a play is nothing without the successful execution on stage, an immersive AR experience idea is nothing without the careful direction of a lead designer. Our societies have always been shaped by the storytellers and the best AR designers will serve the next generation of great storytellers.

Combining insights from across the humanities and technology Christopher Mc Alorum writes on emerging technologies that augment the landscape. His website is www.christopher-mcalorum.com.