Among journalists, no one has gotten inside the story of the Oculus Rift as much as Blake Harris, who has just published The History of The Future: Oculus, Facebook, and the Revolution, a book about Oculus founder Palmer Luckey and the creation of the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset.

In part one of our coverage, we published a transcript of a talk that Harris gave at a book reading in Mountain View, California. This is part two of the conversation, where I interviewed Harris extensively about how he did his research, his interaction with Facebook, and his close relationship with Luckey.

I covered the news about Oculus early on, writing stories on a regular basis. But Harris tried to soak in the whole story over four years, and the result is a 500-page book that talks about the insider view of the stories and events that I covered.

Harris spoke to Luckey almost daily during the four years it took to write the book. And he had exclusive access to executives at Oculus and Facebook — until Luckey got fired in March 2017. After that, Harris lost his access, but he was still able to finish the book.

In the book, we see the role that CEO Mark Zuckerberg played in Luckey’s departure, as well as the fraying of the relationship among the top leaders. We asked Facebook for a comment to some of the stories in the book, but did not receive a response.

I think this one was even better than Harris’ first book — Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo and the Battle that defined a generation — which came out in 2014 and chronicled the fight between Sega and Nintendo in the 1990s as Sega stole a march on Nintendo with the launch of the Sega Genesis. The book was written in a dramatic way, and it was licensed for a film adaptation by Hollywood directors Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Author Blake Harris, writer of The History of the Future.

GamesBeat: I wondered about your journalistic enterprise of doing this, how you approached it. From doing my own books [on the Xbox and Xbox 360], I had some interesting experiences as well. On the first book I had more than 200 questions for Microsoft when I was fact-checking and otherwise making sure what I had was correct. They chose to answer none of those questions. It was funny. On the second book, I worked with Microsoft again to get access and all that, and they answered every question I had.

Blake Harris: What would you attribute that to? Regret from the first time around, or just different people involved?

GamesBeat: Maybe regret? I think they knew that some stories were going to get written from a certain point of view, or some facts would be relayed from a certain point of view. They wanted to make sure that, the second time, they were more engaged.

I wanted to ask you generally, then, what was your working relationship with Oculus and Facebook like over time? You summarized some of the big points in your talk, but did you have certain ground rules going in as you pitched it to them?

Harris: I’ll be pretty broad about this. After Console Wars, at either E3 or Comic-Con, I was talking with Tom Kalinske and Al Wilson and Michael Kiraz, who’s the son of someone mentioned in the book. At that point I was thinking about doing my next book about Rovio, the company that did Angry Birds. Tom said, “No, you should do something better than that.” I was also very interested in VR and Oculus, but I didn’t think I could get access to that. Tom just said, “No, definitely do that.” Michael, who was at Nyko at the time, he knew Palmer and offered to introduce me.

I was introduced to Palmer in July 2014. I proposed the idea of getting interviews and writing a book. He replied, at that time, that several journalists had reached out with similar requests, and in his opinion Oculus hadn’t accomplished anything yet. They now had to go from selling a dev kit to a mainstream product. But at the same time, he liked Console Wars, as did some other people there, so he was at least open to a conversation.

We had that conversation over the next five months. I went out to Menlo Park in December 2014. I was hoping to leave there with access, but that didn’t happen. It ended up taking 14 months after that to get access from Oculus and Facebook. Even at that point, what I was asking for was them letting me speak with the main players and setting up interviews. But they ended up giving me exclusive access, or at least choosing to work with me and not work with any other authors.

The way it was set up was that they would introduce me to anybody that I wanted to talk to at the company, and it was up to that person whether they wanted to speak with me or not. Then, after the introduction was made, I could have my own relationship to them. Some people I spoke with every day or every few days. Some people I only spoke with once. There were no parameters set on the relationship, which was good. I could ask anything I wanted.

Above: The History of the Future captures the rebirth of VR.

I assumed that part of that, to some degree, is because as with Console Wars and everything else I’ve ever written in non-fiction, I told them that I would be planning to share most if not all of what I wrote based on information that they gave me and give them a chance to review. I was very clear that that didn’t mean I would do what they told me to after review, but I would welcome their input. That helps with fact-checking. I’ll make any changes of a factual nature.

That continued for two years. It was February 9, 2016 that was the first day I had my interviews with Brendan and Nate. I think it was February 10, early February of 2018, when I had what turned out to be my last trip to Menlo Park to interview Ed Bosworth, Hugo Barra, Max Cohen, and a few others. Part of the purpose of that trip was, I had recently shared with them the first 60 percent of the book. I big part of the trip was to get feedback in addition to those interviews I had. I also met in a group meeting with Brendan, Nate, their head of comms, their legal team, and a bunch of others. Then I had follow-up calls with them.

Obviously the second half of the book has more of the stuff that they aren’t happy to see published. The first half of the book, they went through all of it and let me know about anything they believed was factually incorrect. Then I did follow-ups to confirm that or not. I think I talked about the dissolution of the relationship before, but I’m happy to go into any more detail you want.

GamesBeat: It sounds like you were comfortable with sharing what you wrote ahead of time because of that rule that you really—it was still up to you as to what got written. It’s not as if they were allowed to have some kind of prior restraint on you.

Harris: Yeah. To that point, I very specifically—what comes to mind is when I had a call with Nate Mitchell with a couple of hours. He asked me if I could please not include him and Palmer being in the car with Jack McCauley as Jack was making some racist comments. Nate was embarrassed that he didn’t reprimand Jack. I felt that was important to include, but I asked him, “Are all these statements accurate?” He said, “Yes, but it’s not a good look for me.” I said, “Okay, I’ll consider not including it,” but I felt like it was relevant, so that was in there. That happened with a lot of things.

GamesBeat: There was the notion that you had to reconstruct some things. The firsthand, secondhand, and transposed sort of note that’s in the beginning.

Harris: I’m pretty disappointed by how that ended up being printed in the book. That went through legal, and it was really pared down to limit liability as much as possible. I think the most significant point is “transposed” in particular, because I did change my approach after Console Wars.

I might have said this during the signing, but there are obviously 15 or 20 percent of people who didn’t like the dialogue aspect of Console Wars. I still stand behind that choice. I wish I had mentioned it in the front of Console Wars — that I collaborated with these people, that I wasn’t just making stuff up off the top of my head. But there was some validity—I can understand the concern. And because this book was so much more recent, because there were email records, and because I recorded every conversation I had with people, I felt it was important to try to do better.

The rule I had for myself was that every line of dialogue in the book is something that I have in an audio file. It’s either a first-person recollection or a second-person recollection. All of it is verbatim from these people. That was very much a documentary-style format, where you can have someone remembering their own experience or telling a story. It’s always in their own words, as opposed to my words.

Above: The Oculus VR team

GamesBeat: Dialogue is a better way to tell a story in your view, then? You don’t want the “according to so-and-so in an interview he gave to Rolling Stone”—you don’t want that mucking up the text and making it less readable.

Harris: As someone who’s spent several years doing documentary work, I’m very much a believer in the idea that how somebody says something is almost as interesting as what they say. It’s also about what they choose to say. A lot of times Palmer says things that seem to come out of left field, or he makes weird connections. To me that’s central to understanding him, and there are similar cases with other characters. Particularly, anything that’s longer than one sentence in dialogue, I’d say that’s almost definitely from the source themselves. There’s a lot of good Palmer rants and Brendan talking in Brendan’s style.

The dialogue is critically important. It’s how we interact, and especially, it’s how we remember how we interacted. Body language is a big part of it, but most of the time people remember the words in our interactions more than anything.

GamesBeat: Having lived through some of this, I can see that there’s a lot that’s left out. What’s here feels like Palmer’s story. Did you view it that way, that whatever you wanted to include or not include in this had a lot to do with the main character of the story?

Harris: I think that’s fair. I would expand it to say, though—I remember the first time I met with Brendan in February 2016. He asked me, outside of his office, “What’s your vision for this book?” It was very early, but at the time I said I imagined it as a marriage between Palmer and Brendan, and by Brendan I also meant Nate and the rest of the Scaleform mafia. I wanted the four of them, or in particular Palmer and Brendan, to be the prism of the story.

That said, without Brendan [Iribe, CEO of Oculus VR]—he couldn’t weigh in, and I couldn’t have his feedback, or even him talking about some of the events at the very end of the book. I didn’t have his feedback on the second half of the book. I probably defaulted more to Palmer’s perspective, as well as for other reasons you can guess. I think this stuff is pretty interesting from his perspective. But I did want to tell a lot of the story from Brendan and Palmer’s perspectives and what they felt was important.

GamesBeat: You explained at the reading about the loss of access at a certain point. Were you talking to Palmer just about every day to that point? Do you feel like you really got to know him, what kind of person he was?

Harris: I’ve spoken to Palmer almost every day for the past three years. You form a close relationship with someone. Other than my wife, I don’t think I could say that about anyone. I do think I know him very well. I think I know him better than almost anyone in the world, other than his girlfriend or his family.

But at the same time, he’s not the only person I was speaking with. He was probably the only person I spoke with every day, but there were other people I spoke with every couple days, whose names I will not mention, because they’re still at the company and they probably don’t want it known that they continue talking to me.

Above: Nicole Edelmann and Palmer Luckey cosplay as Quiet.

I guess the point I want to make is that I do think I know Palmer extremely well. That level of access was critical to telling the story in a successful way. But given that approach, I was always very wary that my story might be slanted by his perspective or my own personal bias, unconsciously or consciously. I tried to put as many checks into place as possible to avoid that happening, and really think critically and get frequent feedback from other people at the company.

GamesBeat: Did you feel like he was misunderstood, like he got a raw deal not only from Facebook, but from the public?

Harris: Yeah, obviously. I think he was treated very unfairly by Facebook and treated very unfairly by the media. But at the same time, I think he made more mistakes than he admits that he made. Just the fact that I think he made a mistake to donate to Nimble America in the fashion that he did, without doing any due diligence–I understand why he did so anonymously, but the idea of fashioning a persona, the nimble rich man persona, around it–whether or not he actually wrote the words, he did essentially endorse those words. That was in poor taste. I don’t think he necessarily feels that he made a mistake in that regard.

All that said, I don’t think his mistake warrants the reaction. I think that was based on misinformation. I especially don’t think it warrants the way he was treated by Facebook, and in particular I’m shocked by the fact that Zuckerberg forced him to write a statement supporting a candidate other than the one that he actually planned to support.

Above: Brendan Iribe, former head of Facebook’s Oculus VR division.

GamesBeat: I was curious about that. Did Facebook ever respond to that and say, “No, we didn’t do that”? You say that very authoritatively, and so I wanted to check that if they ever disputed it.

Harris: I’ve actually been surprised by how few people–fortunately people have accepted this as the truth, which is good, because I believe that this is the truth after years of research. But it is such an enormous claim. I mean, it’s illegal. It’s very unethical. This is something that I was hesitant to write unless I had really good sourcing on it. I know the lawyers at Harper Collins felt the same way. I ended up getting emails, some of which I got after my final draft, but before publication, to try to bring something to the lawyers.

That’s a long-winded way of saying that in the second edition of the book, I’m going to have even more from the actual emails. But there is an email from Facebook’s general counsel to Palmer’s employment attorney saying that Mark himself drafted this and the details are critical. The other thing is, that could all be true, but then maybe the version that Mark drafted was very similar to the version that Palmer drafted, even though I had heard otherwise. I was finally able to get a copy of Palmer’s early drafts, and they bear no resemblance to what was eventually posted. I needed to be very careful about that. I feel very confident.

To answer your question about Facebook, initially–part of the reason that the relationship fell apart was because I had a conversation–I was told the same thing by several people. They all told me that it was Palmer’s choice to say he voted for Gary Johnson. But they also told me that in the context that they didn’t even know he was a Trump supporter, that he was always a Gary Johnson supporter. In particular, in one conversation, I replied to them and said I knew for a fact that he was a Trump supporter. I talked about it with him frequently to try to understand why he felt that way. That really threw them off. They made a lot of comments that were not true with regards to that, and then they never responded one way or the other.

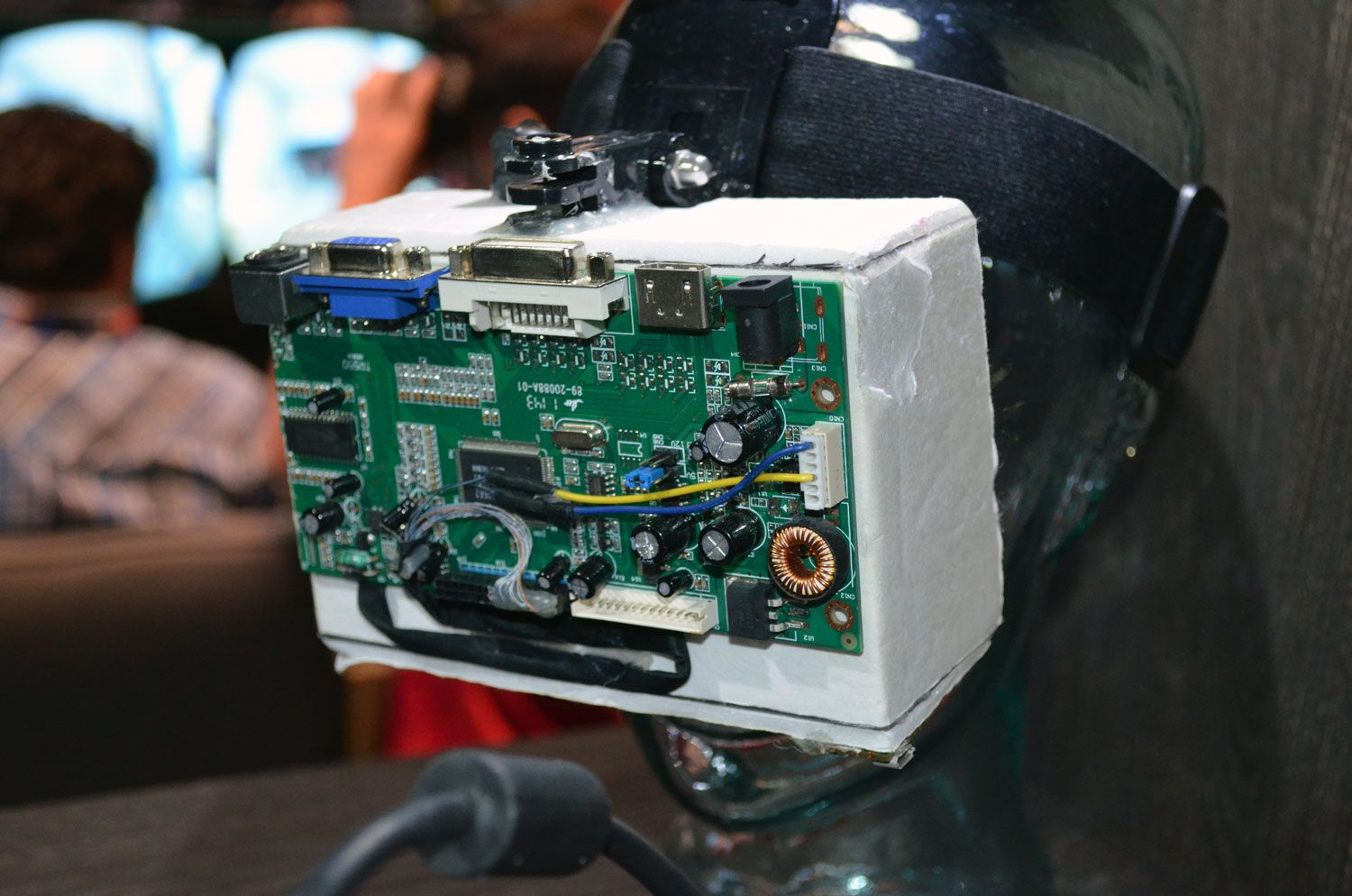

Above: Oculus Rift prototype

GamesBeat: There are quite a few mysteries still that surround the firing. I thought it was interesting when you went on Fox and talked about this some. You mentioned that you were a liberal yourself, and you didn’t necessarily agree with Palmer’s political beliefs.

Harris: That’s right.

Above: Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook CEO, in the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset as Oculus VR CEO Brendan Iribe looks on.

GamesBeat: It sounded like you had to be careful in this particular part of the story.

Harris: Yeah. I would also say that it was kind of like–I don’t want to be too dramatic, but it was emotionally grueling for me, the whole process. I felt like, at the end of the day, Palmer had been very mistreated by his employer and by the media for being a Trump supporter. I felt like, in a sense, getting the truth, or at least the stuff I was uncovering, was going to absolve him. The idea of spending two years working to absolve a Trump supporter for his support of Trump–I don’t know if that was a mission I would have initially cared to set out for.

But at the end of the day, there are two things. I absolutely disagree with Palmer on a lot of political issues, and in particular around Trump. I feel like with Trump, someone could have the perspective of, his rhetoric doesn’t matter, and all that matters is his actions. Maybe it’s because I’m a writer and I deal with words for a living, but I absolutely disagree with that. At the same time, as much as I dislike Trump, I don’t find his supporters offensive purely because of their support of Trump. I find Trump offensive. But I can understand why he can be selected as a lesser of two evils, or why certain people could prioritize a Supreme Court seat or not going to war overseas.

The other thing that I found humbling, that gave me some optimism–after Facebook lied to me about what happened with Palmer–I should probably talk a bit about his exit, because I’ve since learned some things, and the different versions of the story are interesting. After I was told what I suspected might have been not true, or seemed a little puzzling, when they went as far as to say as it was Palmer’s choice to leave, I ended up bringing that to people that I trusted at Oculus and Facebook. People who I know are fellow liberals, as well as some Trump supporters there. I said, “Look, if you guys don’t help me tell a different story, this is all that I have. I can’t just write about my hunch that there’s a different version.”

It was really nice, to me, that people there on different ends of the political spectrum still felt Palmer was wronged. They were willing to stick their necks out to get me the details on what actually happened. I always thought this was more about principle than about a partisan position.

GamesBeat: In some ways it’s easy to start pointing fingers in this kind of situation. “Why didn’t Palmer behave in a different way? Why did he make that donation? Why did he continue to go to Trump rallies?” But that gets to–it’s beside the point. It’s not illegal for him to do that.

Harris: The legal issue is one thing. That’s pretty black and white. It’s not illegal for him to do it, and what happened to him was illegal. There’s also the ethical aspect, though, and that’s important. Especially because–I live in a liberal bubble too. But half of our country, 40 percent of our country, does feel differently. A lot of those people have valid reasons for feeling that way, as opposed to just anger or nationalism.

Going back to what I said about how this was a grueling experience for me, it really did force me to confront a lot of my own beliefs. I think I was personally intolerant of other views, or I assumed that liberal views were correct views. Spending a lot of time talking to Palmer, talking to the founder of Nimble America, and thinking about what I believe–if a colleague of mine believed in certain things, would I be okay with that?

Above: The early Oculus VR team

GamesBeat: You don’t want to be painted as the guy who’s defending someone who’s really not a nice person, a hateful person.

Harris: Right. That’s a big thing. Fortunately, because I had been in touch with Palmer at that point — I’d spoken to him every day for a year — I had a pretty good sense about who he was and what he believed. Now, two years after that, I feel even more confident that I have an accurate assessment of him. But I was very concerned that it was possible that Palmer donated to Nimble America and didn’t really know that much about what it was, and that the founders were hateful people, white supremacists. In my first calls with them, they were kind of snowing me, kind of making me hear what I wanted to hear.

But I did, over the course of–I think it was about a year and a half. I probably had about 10 hours of conversations with the Nimble America founder, a guy named Michael Maliovsky in the book. I genuinely believe that what he told me was true, and that seems to be backed up by his Reddit posts. I remember at one point, my heart sunk when I pulled up–I was able to get an archive page of his Reddit before he deleted it, and I saw he was a moderator for the Daily Stormer. I thought, “Oh my God, he’s a Nazi.” But then it turned out that was just him trolling Nazis. Okay, I’m not helping a very bad person here.

GamesBeat: That did make a difference to you? That you want to write about a person who isn’t hateful.

Harris: Yeah. Look, at the end of the day I was going to follow the facts where they led me. I would have done the same thing even if it turned out that it was a hateful group. I would have reported that. I would have felt bad about spending so much of my time investigating something that I didn’t believe deserve to exist.

One thing I found very saddening was that–in November, three months before the book’s publication, I shared some chapters with high-ranking folks at Oculus and Facebook who had declined to speak to me. At this point it was already too late for them to make changes, but out of respect I shared some of the chapters with them, including the chapters about Nimble America. Multiple people told me, “Wow, I didn’t know that.” These were the people who ended up deciding Palmer’s fate.

I found that staggering, that they had no idea what this thing even was. In fact, one of them had off-handedly mentioned to me that Palmer was involved in a “disinformation campaign.” That wasn’t what this was. I was shocked that they didn’t have any personal curiosity about this. I was personally curious about it — Palmer, what kind of stuff was he mixed up in? What kind of guy is he? And if not for the sake of my book, at least for the sake of them evaluating whether he should have a job there, you’d think they would triple-check that and make sure they knew exactly what he was involved in.

Above: Founders signing the first Oculus Rifts.

GamesBeat: It sounds like the internal investigation you mentioned there didn’t serve Facebook very well.

Harris: I have to say, I was shocked that the internal investigation didn’t turn up something. I figured that they would find something Palmer had done wrong, but I guess that speaks to how he acted professionally. We are all, as consumers of the media, sort of scarred by the depiction of Palmer. Even though it turned out to be largely untrue, I still think that our opinion of him changed a bit. I mention that to say that I think people now remember him or think about him as more of a rabble-rouser, kind of naughty, pushing the limits at work. But that didn’t happen. Since then he’s cosplayed in a bikini and definitely lived his life out loud a bit more, but he didn’t do those things while he was at Facebook. He was largely a model employee. He has his personality. He’s naive in certain ways. He’s excitable. But it wasn’t as if–

GamesBeat: He seems more like an independent thinker. Like a likable kid.

Harris: It’s kind of sad. When I was talking with [another writer], who’s doing a book on Facebook, he made an observation that I thought was very spot-on, that it was kind of sad–or I guess he didn’t say it was sad. But he made the observation that Facebook’s campus is One Hacker Way. Mark’s a hacker. He saw a lot of the young Mark in Palmer. The fact that Mark had no place for Palmer in his company shows that Mark wouldn’t have a place for a younger version of himself in his company. That shows a lot about how Facebook has changed.

GamesBeat: I also wonder whether they were just mad about the lawsuit, what Palmer might have done that messed them up on that. But that seems like a false trail as well.

Harris: That was one of my initial instincts as well, given the timing of the firing. But it was always very significant to me that they told him to pack up his office and took away his admin privileges the day they rested the case, not the day of the verdict. This wasn’t a reaction to the verdict.

Palmer, when I suggested that was a potential motivation–and by the way, Facebook never told me this. They told me a lot of things, but they never suggested that that was what it was given the timing. But when I suggested to Palmer that certain people think that, he said it was ridiculous. During the two years or however many years of legal work, he was never told by Facebook that he’d done anything wrong. I said, “Well, maybe they never told you that because it was in their best interest not to tell you that.” He said, “Yeah, I guess you’re right.” But going over some of the other facts–all of the other charges against him were later reversed. The timing of his firing–I just think that’s a red herring.

GamesBeat: It did sound like they kept him around longer than they wanted, just to help him defend the company during the trial.

Harris: Exactly.

Above: A young Palmer Luckey

GamesBeat: But they wanted him out before that.

Harris: Right. Then you have to look at–basically, Facebook decided–this is speculation on my part. But you have to assume they’d decided that they wanted to fire him pretty soon after what happened, since they didn’t put him back in the office. So why did they keep him around? One plausible explanation is that, because it’s illegal to fire someone for their political beliefs, they wanted to have some intervening time.

The other is that they did want him around for the trial, because he’d agreed to let Facebook defend him, and Facebook’s priority was to–I remember talking to Palmer about this. I said, “If you were not at the company, would you have given different testimony?” He said, “No, it’s not about lying. It’s about strategy.” He was referring to the Facebook attorneys. They focused on Facebook not losing the more important issues, like theft of trade secrets. Because there was a limited amount of time, they might not have had certain witnesses who would have defended Palmer, or even Brendan. So it was really about strategy.

Anyway, it seems really unlikely. The story I’ve heard, the explanation of why Palmer got fired, is that there was no longer a role for him at the company. I find that incredibly hard to believe. I feel that way even more so after he’s put out certain things on his blog, like how to monetize the audio in Oculus Rift. He’s not a useless person. [laughs] He also could have been an asset to appeal to that other half of the country, but that’s another conversation.

GamesBeat: Before I forget, one other thread of thinking I had was around whether or not people came to the conclusion that ZeniMax was right, that Palmer was just a kid, a fool who didn’t know anything, and Carmack was the smart guy who made it all happen. Maybe Facebook believed that and eventually concluded that he didn’t belong. But to me that sounds incorrect in that it assumes that Palmer was technically inept. It sounded, from what you documented in the book, that he really did have a lot of these ideas that they ran with. They relied on him for technical expertise — things like what you do with your hands in VR, the Oculus Touch, that sort of thing.

Harris: Correct. The way that people at Oculus — the people who fired him, the high-ranking Oculus and Facebook talking about Palmer — is exactly the same way as ZeniMax talks about him, as if he was almost this doofus who was in the right place at the right time. He just rode John Carmack’s coattails. It sounds reasonable. But then you look at the facts, and also, like you said, he’s still putting stuff on his blog, the hacks you can do. Then you hear him talk for 20 minutes nonstop about VR and you realize this guy is brilliant. He’s not someone who lucked out. He was obviously very lucky. But not in the way they like to tell it.

GamesBeat: Just from talking to Palmer myself, I know he’s an intelligent guy. It was interesting to see ZeniMax try to paint him that way. I then think, maybe if they believed that he was not technically that valuable, then why did they keep him around? Maybe he kept them around because he told a good story or served as a good spokesperson, but once he was a tainted spokesperson, and the public maybe unfairly vilified him, he was no longer useful.

Harris: I think what you describe there is a large part of their perspective. I think they’d pass a polygraph with that perspective. That’s how people there think and do think is what happened. It’s understandable.

The two things that come to mind with that, and neither of them are refutations–one, I think that if that were the case, then they owe him the opportunity to explain himself to colleagues, and to not be vilified, if public perception is what cost him his job. The other thing is, the way the deal was structured gave him most of the money paid out on the back end. I think it was a shitty thing to do, to fire him before all of his options vested. They have the right to do so, but when you make that acquisition deal and you’re told you’re going to be kept around, it’s reasonable to think you’ll be there for the duration.

Above: Oculus leaders. Palmer Luckey holds a Rift in his hands.

GamesBeat: Some people did refer to him as “the Oculus billionaire.” That didn’t seem like it was true based on my calculations.

Harris: Yes, that’s not true.

GamesBeat: It’s off by hundreds of millions. He did fine, but getting painted as a billionaire–was that part of that vilification?

Harris: Yeah. Brendan made at least twice as much as Palmer made in the deal, and the deal was for $3 billion. But it wasn’t like Palmer made $1 billion and Brendan made $2 billion, though. The stock went up, but–it was like 16 percent. It was nowhere near a billion, but it was obviously an enormous amount of money.

GamesBeat: It was good to see that there were some real behind-the-scenes explanations for a lot of things we all saw from the outside. There was one area I was curious about that I didn’t really see an answer for, though, and that was–why did Valve come back with such a vengeance and do Steam VR?

The only thing I could think of was that–some of what I’d heard publicly was that they wanted there to be choice in the market. They wouldn’t have done VR themselves if Oculus had stayed an independent company, but once they were bought by Facebook, Valve saw that as a closed system. Now they needed the equivalent of something like what Android is to iOS.

Harris: This is speculative on my part, and it’s not in the book, but that’s what I’ve heard as well. I was never able to confirm anything from a primary source, anyone who was in the room for these conversations, even if it was people at Valve, so I didn’t feel like I could report that. But that’s a great example of something you think should have been answered in this book, that would have been good to know. It certainly would have been intriguing and exciting to see them building up after they lost Abrash and others.

Everyone who’s currently at Valve declined to speak with me. I really only reported things that I felt certain about. Unfortunately, that’s not in there. But I’d love–if I could go back in time and see anything, that’s one of my top choices. That’s my white whale, to some degree.

GamesBeat: It’s funny to see Valve in that position, because sometimes they get accused these days of being monopolists, right?

Harris: The whole thing is very funny. Early on, when Gabe says that he doesn’t want VR on Steam, because they only have curated high-quality products–obviously their perspective on that has changed, because they chose more of a democratization of content, to the extent that they’ve allowed a lot of content that people find objectionable. But it’s interesting to see how much they’ve changed there.

It’s also interesting–basically everyone from Oculus and Facebook that I spoke to thinks that Valve was the Goliath, because they had this PC monopoly with Steam, and Oculus was the David. And then the people I spoke with from Valve, although there weren’t very many of them, they said, “Facebook has billions and billions of dollars. They’re the Goliath.” It’s interesting that both of them cast themselves as David in this David and Goliath story. They’re both pretty well off. [laughs]

Above: The Oculus Quest sits behind the Touch controllers.

GamesBeat: You did a good job of conveying all of these things happening very quickly without clogging it all up. There’s just this small scene with the Reddit guy, or a small scene with Phil Chen from HTC, but you get the point, that this was an important part of the narrative, even if it’s not something where you have to do the blow-by-blow.

Harris: I appreciate that. Space was an issue. It was a fight to get it to this length. But in cases like Phil Chen, I could have written five more pages about what happened next and his contributions. Maybe someday I’ll get to that. But I did feel like there was enough there. I wanted to at least make clear that this was a significant event that happened, and you could glean enough about what happened to go from that dot to the partnership with HTC and Valve, their meeting in late 2014.

The degree of difficulty on this book was a lot harder than Console Wars. There were a lot of different stories to juggle. Then there was also just the fact that–Console Wars doesn’t get that much into the hardware. Everyone understands the idea of plugging in a console and playing a game. But this had things like degrees of freedom and different kinds of tracking to explain. It was tough.

GamesBeat: I don’t know if there’s a part I missed or not, but I didn’t see a capsule description of Jason Rubin. I saw his name appear, but I don’t remember seeing him being introduced.

Harris: No, you’re spot on. There’s a few things like that that are very embarrassing to me, that were not caught before publication. The first time I mention Jason Rubin, he’s just referred to as “Rubin,” and later on he’s referred to as “Jason Rubin.” But you’re right. There’s no introduction. Another one is Oculus Touch. You know what Touch is, but I never actually explained that this hand project became Touch. I just start talking about Touch. There are a few places like that where I’m definitely embarrassed. We’ll be correcting them for the next edition. It’s an outright mistake on my part.

GamesBeat: So if you were going to describe Jason Rubin [properly], and his historical significance for Oculus, what would you say?

Harris: Jason Rubin…He and Jason Holtman–often playfully referred to as “The Jasons”–were amongst the first couple of targets that Oculus went after following the acquisition announcement. And while things didn’t quite work out with Holtman, it’s easy to understand why Oculus put Rubin on such a pedestal. Speaking with devs over the past few years, almost all of them who worked with Jason would end up saying something like ‘That guy knows how to make games.’ More importantly to Oculus: he knows how to help others make games; I think that’s something underrated about him–that from Naughty Dog to now he has consistently shown an ability to build games not only from the ground up, but to step in at various stages, provide insightful feedback and help others bring their vision to life.

Above: Superhot VR is coming to Oculus Quest.

GamesBeat: Sometimes you work on these and you wonder what the extra perspective brings to this whole understanding of the story. Sometimes there isn’t any. There’s a risk in writing books, that sometimes you never get to the bottom of things. But to me there’s a payoff in this book. I learned things that I didn’t know after writing a story every week about Oculus.

Harris: I really appreciate that, because that’s important. Getting that sensitive with Zuckerberg and Palmer’s exit was a big part of why it took me longer to finish the book, but a big part of it, too, was what you’re talking about. I could have written, basically, here’s what happened and here’s what happened next, but I don’t know that you would have gotten the holistic conclusion that I felt like I came to by connecting certain dots.

One other thing I wanted to mention related to Palmer’s employment, because I’m looking at a list of things that are going to be included in the next edition. Palmer–another story I was told, and that also sounds viable, is that Palmer did poorly on his performance reviews at Facebook, because Facebook is known to have very high standards for their employee reviews. That was one of the first things I was told by Facebook. Then I got hold of his performance reviews, and they showed he did very well. Just throwing it out there, in case you end up hearing that excuse from Facebook.

What you described, I think, is a big part of it. A significant portion of his job was to be a spokesman, and they felt that he could no longer do that job given then public perception of him, whether it was right or wrong. That’s hard to argue. I just don’t know that that warrants firing someone who has a lot of other responsibilities at the company.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that you didn’t go to a lot of things in person or see a lot of these things. But it does sound like you had so much access to Palmer that you had a lot of things described to you pretty well.

Harris: And not just Palmer. Especially with the events, because there were so many devs there. In the end I probably interviewed, I don’t know, 150 different people. At one point–one thing you see a bit in the book is how critical the community was, things like /r/Oculus on Reddit, and the enthusiasm from developers.

At one point I had a section of the book that was Q&As I’d done with members of the community, partly to capture that enthusiasm and partly to show what they thought of the Oculus/Palmer relationship, because they seemed to have some misconceptions that were understandable, given how Oculus wasn’t messaging and the closed-door nature of it all. I ended up not including that. But those people were very helpful to me as far as the events in VR over the past few years.

Above: Palmer Luckey on the cover of Time in August 2015.

GamesBeat: It did seem that Palmer was really the one that saved their reputation in the wake of the acquisition.

Harris: It’s interesting now, after two years of him as a villain, to see what he’s doing now with Anduril. Anduril being in defense technology, it’s much more serious, much more life-or-death stuff, and it’s incredibly valid if someone has issues with what they’re doing. Or at least skepticism. But it’s nice to see him out there evangelizing for why he thinks that Silicon Valley and technology enthusiasts should be working with the defense sector. It reminds me a lot of the early days of Oculus, going out there and just trying to change the public perception of VR. I see a lot of those some qualities exhibited today.

Although again, it’s an entirely different situation, and I’m personally skeptical. I have a healthy skepticism about what Anduril is doing. I want to know more.

GamesBeat: That was the border control technology, using AI?

Harris: Yeah, yeah. There was a story over the weekend about a project made on contract to do AI for drones. I think these are some scary-sounding things, and I think the public should know more about them.

GamesBeat: Did you get any feedback that you thought was really worth mentioning from any of the principle players that have read the book?

Harris: This is going to sound like bragging, but–their feedback is what I care about most, because it’s the barometer of whether I did a good job or not. I could send you a few of the comments, just telling me that I nailed it. The management of Oculus and Facebook have alleged, non-specifically, that there are factual inaccuracies in the book. Hearing from the people who lived it that, no, there are no factual inaccuracies at all, or at least among the things they can personally confirm, that made me feel really good.

GamesBeat: We talked a lot about Palmer. Did you come away with any particular impression of Brendan?

Harris: I will say that I think it’s saddening that Brendan didn’t seem to be there for Palmer when Palmer needed him most, or could have used some clarity. But their relationship aside, I can’t imagine a better person to run a startup than Brendan. He’s incredible. Building out a vision, recruiting the team, and building a company, building assets–I think that hopefully the book speaks to his entrepreneurial prowess.