Above: Oculus Quest has no wires, so you can play tennis in VR without tripping.

I started to think a lot about the show Mad Men, which has always been one of my favorite inspirations. There’s a quote at the beginning of the book. If you were going to make a documentary about advertising agencies in the ‘60s, or tell a story about advertising agencies, you can go to different agencies and show different perspectives, or you can really just stick with Sterling Cooper and, through them, see a lot of what else was out there. The priority is still these characters and Sterling Cooper, so you’re not going to going to go out of your way and have a chapter on the Google VR project. But you’ll at least become familiar with it. That’s what I ended up opting to do.

Another–”challenge” maybe isn’t the right word, but another thing I thought about a lot–because this is a book about current events, and because I had a lot of information I thought would be newsworthy, there was maybe an approach to optimize the book toward getting out breaking news. For a while that was a direction I went in. Call me a romantic, but I like to think of good books as timeless. I wanted this to be a book like Console Wars that was still read five years later. I didn’t want to have to rely on these juicy morsels, or the perception that there would be information that you have to read now.

There’s a lot of other ways to get that out there. I could write an article. If I can’t dive into something I can share it with another journalist and see if they’re interested in it. I ended up really–the more the VR and AR ecosystem expanded, and expanded so quickly during what felt like the gold rush period, the more I stuck the scope of the book to focusing on Oculus and trying to see through the eyes of those core characters.

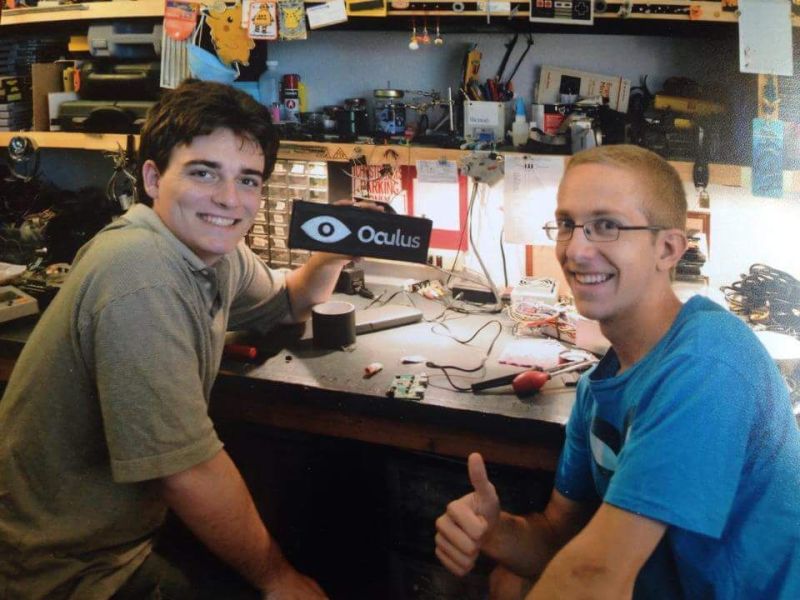

Above: Palmer Luckey (founder, left) of Oculus and Chris Dycus, employee No. 1.

Question: Palmer was very young when all of this happened. I’ve talked to him a couple of times. It’s clear that he was sort of astounded by it all. He was very much a kid. He talked about–when the deal with Facebook was consummated, he had more money to buy the juice that he liked. Things like that. Do you think that if all of that had happened 10 years later, if it’s the same sequence of events? Do you think he’ll be fundamentally the same person 10 years from now?

Harris: A lot of people like you, who I’ve been in touch with while writing the book, trying to pick your brain and share a little of what I’ve found–basically, I’m saying people who are open to the idea that what was reported was not fully accurate. The usual thought is, “Oh, Palmer’s just young, so it’s a stupid young person mistake.”

I think that because of what happened, and feeling like he was pushed out of his company the way it went, that did fundamentally change him. Even just looking at his new company, he’s much more careful about making sure to retain voting shares, to make sure he can’t get kicked out of the company. But as far as the starry-eyed lackadaisical approach, or almost just the childlike wonder, I think that hasn’t changed.

To me, one of the more significant conversations in the book is, after the Nimble America thing happens and it becomes a big deal and it’s reported that he’s funding this racist troll group or whatever–basically, after the worst comes out, true or not, he returns home from where he was during this period of time. He happened to be taking his first vacation since joining the company. He returns home to his four closest friends, his roommates, the people who had been with him since before Oculus, from his original message board–these people are as close to him as family, or probably closer from getting to know them over the years. Their question to him is, “What the hell?” And he jokes around at first, because that’s his way, but he doesn’t seem to show any contrition for what he did. In his mind–I think he referred to it as a “fun lark.”

On the one hand you could say he’s just not fully grasping the gravity of it, or that’s just how he thinks it should be, that people should think of it as a fun lark, even though a lot of people don’t. But I thought that was really significant, to have all those people in that conversation with him and to go through it all with them, go through the conversation so I could get it. It seemed like that would be a moment of pure honesty on his part.

I still talk to him almost every day, and I’ve never heard him say, “I shouldn’t have done that, or I should have done it in a different way.” His mentality is more like, “Why do people care about this?” There’s something to be said for that. But he’s also a smart guy. He should probably know that people are going to care about it, whether or not they “should.”

Above: Hayden Dingman at PCWorld testing out the Oculus Quest

Question: Do you still think VR is going to be as big a deal as everybody thought it would?

Harris: It’s something I’ve thought about a lot, now that I’ve had more time to think about the bigger picture and not focus on this story. Like a lot of people, even a lot of you in this room, my real interest in this book–Popular Mechanics got me interested in the story, but what made me want to spend years of my life working on this was my first VR experience, taking it off and literally just saying, “Wow, that was the future.” Then processing what that means, or how a company could monetize this, or what would be the business of it. Is this a platform? Is it a peripheral? What is happening here?

I preface with that to say that I still get that feeling a lot when I try VR. I don’t feel like I’m jaded by it. I’m still very frequently awed. But there’s also the reality of how things have gone over the past few years. You talked earlier about the chapter with the indie developers. A large part of my interest in that is because I find it beautiful that people would take such big risks for something they believe in, even if there’s not necessarily a financial goal or if it’s an unknown. At the same time, I did think it was significant that almost all of those people are no longer doing VR. Or at least Playful and Paul Bettner and company, who created Lucky’s Tale, and CCP, who created the other bundled game–I think it’s significant that those two companies, who were the first to jump in, the first to drink this Kool-Aid to be first for this thing that was going to make billions of dollars, they aren’t in VR anymore.

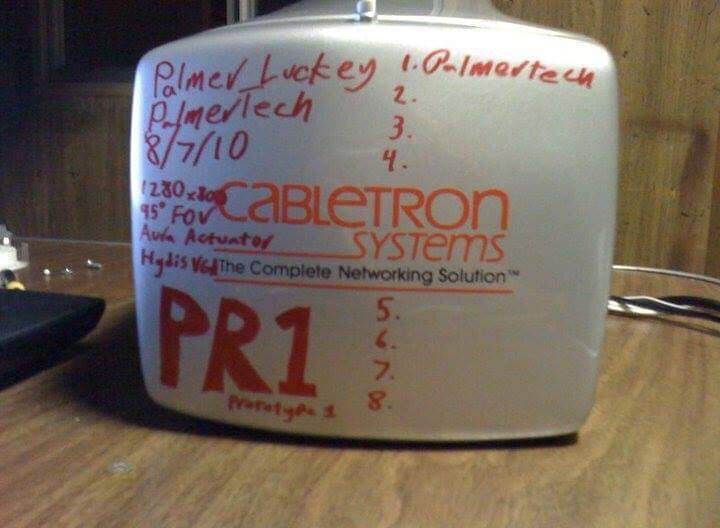

Above: Palmer Luckey’s first prototype of the Oculus VR headset.

It’s certainly not for a lack of passion. Or at least at Playful that’s the case. I haven’t spoken to the current team at CCP. There is this reality that we have to face, and I think that–I’ve been thinking more and more about something that Palmer told me, that I probably should have put into the book.

In an early conversation between him and Brendan, the CEO, Palmer has explicitly told me–he said, “I’m the person who started Oculus. Without me there would be no Oculus. But without Brendan it wouldn’t have been successful.” He credits Brendan for as much or even more of the success than himself. Very early on, during their first meeting actually, Brendan was talking about how big of a deal this is going to be, how this is going to change the world. Palmer felt the same way. He just felt it was going to take longer.

What I liked about that conversation was that Brendan, and very much how Mark Zuckerberg and a lot of other people have framed the expectations for VR–he saw it as a somewhat similar trajectory to smartphones and mobile computing. You go from Blackberry to iPhone, and within three to five years it’s ubiquitous, with millions and millions of phones. Palmer, at least back then — I’m not sure if he still feels the same way — he compared it to the PC revolution, where you had companies like Apple in the late ‘70s making PCs for more of a homebrew crowd. People were actually putting computers together, like Palmer’s original vision. It probably wouldn’t have gone anywhere. So you did need that hype and that excitement.

But I think that it’s looking more and more like, at best, it would be the PC evolution. In addition to it appealing to enthusiasts and people willing to brave the wild west era of the technology and the marketplace–if you look at how Apple excelled in the late ‘70s, you would say the PC revolution started then. But my family didn’t own a computer until the mid-’90s. That, to me, is when it became mainstream. That’s 15 years.

I don’t think this is going to take 15 years, if it happens at all, but what happened largely between the late ‘70s and when it got to my family was computers being used for business and enterprise purposes. That’s where we are seeing some strength for VR, whether it’s for training, for the military, for health care. I guess the short answer is I’m still as bullish and excited about VR as I was, but I don’t think it’s going to be something that my mom is going to buy, or call me up and ask how to use, in anywhere near the timetable I’d originally thought about.

Above: Author Blake Harris, writer of The History of the Future.

Question: When you were writing this, were you relying primarily on interviews, staying in New York to write and working through correspondence? Or did you try to get some first-hand accounts of what was going on? Did you got to Oculus Connect, to VR LA? Did you come out to California to get down on the ground?

Harris: Almost exclusively I relied on secondhand. In general I’m a homebody. I like to be removed from it. But I also realize that maybe that’s just an excuse because I’m a homebody. For a large portion of writing the book I had a really bad lower back issue. I was walking with a cane and not very mobile. That also contributed to why it took me so long.

But it is almost exclusively secondhand, and for that reason, my favorite compliments have been not from press, or excited readers even, but from people at Oculus in those early days saying, “You really captured it. It’s like you were there.” At least that makes me believe it can be done when you’re not there.