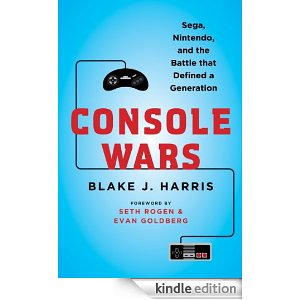

Blake Harris is a historian of the video game wars. His first book — Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo and the Battle that defined a generation — came out in 2014 and it chronicled the fight between Sega and Nintendo in the 1990s as Sega stole a march on Nintendo with the launch of the Sega Genesis. The book was written in a dramatic way, and it was licensed for a film adaptation by Hollywood directors Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg.

That book’s success let Harris quit his day job as a Wall Street trader, and it enabled him to research his newest book, The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook, and the revolution that swept virtual reality. Harris spent more than four years on the book, with close access to Palmer Luckey, who founded Oculus as a 19-year-old living in a trailer in front of his parents’ house.

After Facebook acquired Oculus in 2014 for nearly $3 billion, Harris was able to get exclusive access to the executive team to chronicle the revival of virtual reality. But after Luckey was let go in March 2017 and Facebook learned the inside story that Harris was picking up, he lost access. That made his work harder, but Harris persevered and published a 500-page tome on the story.

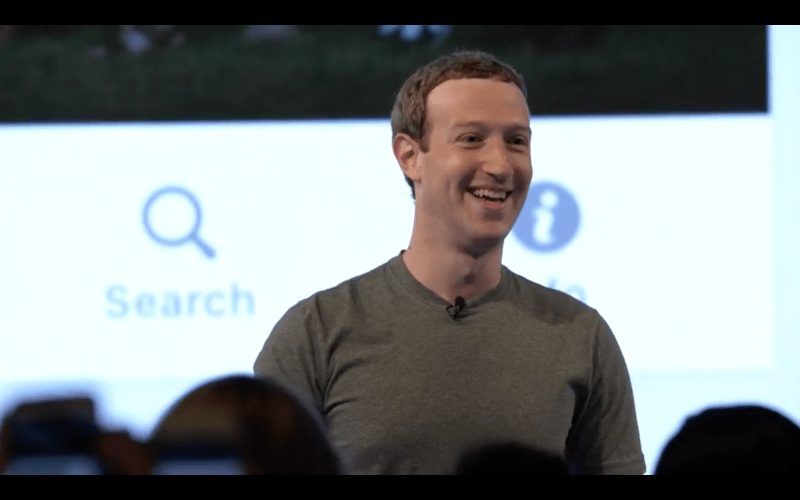

In the book, we see the role that CEO Mark Zuckerberg played in Luckey’s departure, as well as the fraying of the relationship among the top leaders. We asked Facebook for a comment to some of the stories in the book, but did not receive a response. I attended a book reading that Harris gave in Mountain View, California, and this is a transcript of that session. In it, I asked some questions, as did members of the audience. I also did an interview with Harris that will run on another day. I found Harris’ talk, interview, and book to be very illuminating on the history that I covered on a day-to-day basis as a writer at GamesBeat.

Here’s an edited preview of our interview.

Above: Blake Harris is the author of Console Wars and The History of the Future.

Blake Harris: Ten years ago, or even seven years ago, I had a day job trading commodities for a financial brokerage in New York. I was working for Brazilian clients, trading coffee and soybeans and corn and all this stuff. When I first started out of college, it was fun. It was a lot like the movie Trading Places, with all that chaos. Then everything went electronic and it wasn’t very fun, but that gave me more time to daydream about writing.

Throughout my 20s I was screenwriting on the side, very unsuccessfully. I ended up spending all the money I had saved up from this job making movies, also very unsuccessfully. One of the big turning points for me, a disappointing turning point, was that my screenwriting partner and I wrote a script called The Sordid Tales of an Evil Tyrannical Ex-Dictator. It was about a dictator who was overthrown from his country in Europe, comes to the United States, and works at a DMV in the Witness Protection Program. This was the script we were sure was going to finally break us and make us millions of dollars and launch our careers and let me wear shorts every day. Then, a week after we finished it and sent it to our manager, Sacha Baron-Cohen announced he was doing a movie called The Dictator. Everything we had put together was immediately worthless.

I understood that. If I was a studio I’d much rather bet on Sacha Baron-Cohen, who has a great track record and is very funny, than me and my buddy Jonah. Around that time — I was probably 27 years old — I’d always been hoping to make it as a writer, I was starting to think that maybe wouldn’t happen. I guess I had always imagined somewhere in my mind — this was probably inspired by Dave Coulier on Full House — if I don’t make it by the time I was 30 or 35, I was going to give this up, it was never going to happen.

But I was always going to write, and since I was going to do that, I wanted to make sure to write things I really love, because there’s always a possibility that Sacha Baron-Cohen might be working on a similar project, and what I’m doing might end up being–not worthless, but commercially not viable.

As seems to often be the case when I’ve interviewed people who found success, the one project that I set out to do with no monetary goal in mind was the one that ended up being successful. It doesn’t always work that way, but it tends to be in the ballpark. This was the one I did purely out of passion and not to try to fit some template of an action comedy about a dictator.

Above: The Oculus Rift.

Before I even set out to write Console Wars, I really just wanted to read it. I grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s. I now, as an adult, love behind the scenes business stories. I remember going to a Barnes and Noble on 86th Street in Manhattan — I live in New York — and asking where the video game history section was, thinking it would be near the music history or film history. Then I learned that there was no such section in the store, and there wasn’t even a single book in the store about video games, the history of video games, the business of video games. The only somewhat related thing they had were walkthrough guides.

That just seemed very odd to me. At the time I hadn’t played games in many years, but I knew it was a big industry. I liked watching other people play. I’m very bad at video games, which is partly why I don’t play all that much. But I love the industry and I love what’s being done out there. And so, again, before even really imagining that there was a project here, I just started trying to get in touch with Sega and Nintendo employees from the early ‘90s.

My biggest worry was that–as a kid growing up I imagined that working at Sega or Nintendo was like working at Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. Although I guess the working conditions weren’t that great there. Like going to his factory, maybe. I would talk to these people and they would say, “No, working at Sega and Nintendo was just like any job, punching a time card.” But almost everyone I spoke with, especially in the beginning, they described it as the greatest experience of their lives. That was inspiring to me.

I ended up accumulating more and more contacts and starting to put together an outline and a story. Console Wars is essentially a narrative, a case study, of how Sega went from five percent of the market to 55 percent of the market and toppled Nintendo’s monopoly, and then shot straight back down. The rising part of that trajectory, there’s a lot of business lessons I learned. One of them was that Sega did a really good job of identifying that they were an unknown, as was I, and they aligned themselves with younger celebrities who would help their brand.

I literally googled for celebrity gamers and Seth Rogen’s name came up. He was definitely out of my league. I didn’t expect to hear back from him. But I knew this guy liked Nintendo, probably also liked Sega, so I had my manager send him a copy of a treatment I put together. Miraculously, he was interested in meeting. I met with him and his partner Evan Goldberg in January of 2012, seven years ago now, and I remember meeting with them on a Thursday. Not only was it surreal and unusual to be hobnobbing with someone who I knew from the movies, but I remember thinking, “Wow, this is the first time I’ve ever had a meeting with an actual decision-maker.” I’d always met with creative executives that would end up with us telling each other that our people would call each other and nothing would happen.

At the end of that meeting–we spoke for a couple of hours, and then later that day I got a call that Seth wanted to produce a movie based on the book that I hadn’t written yet. But I had interviewed about 100 people, so I had a good sense of the story. He also wanted to produce a documentary. That was amazing and life-changing. I remember going back to my commodities job four days later on Monday and thinking, “Wait, my life was supposed to change, but I’m back to work at 6:30.”

Eventually Scott Rudin joined the project, and we ended up going out with the book proposal. Flash forward a bit from here, but the last note here was that I remember, when we went out with the book proposal, that even with this great package of people who were way more successful than I was, who were making movies and documentaries based on this–we went to 25 publishers, and 22 of them passed because they said video game books don’t sell. I remember thinking that was a weird thing to say. That’s a segue way to saying that if anyone out there is interested in writing a video game book, I always try to make myself available to provide advice, because I thought that was a pretty crazy thing for them to say. I’m glad that Console Wars sold well, and I like reading video game books, so if you have an idea, get in touch.

That came out in May 2014. It was a very big, life-changing experience for me. I quit my day job. I remember telling my manager that it was kind of sad that I would never write a book as good as Console Wars, and he said, “No, you’ll keep getting better with each book.” I said, “Well, I hope so, but I’ll never find a topic that has such a convergence of pop culture, technology, entertainment, larger than life personalities, and billions of dollars.”

It remains to be seen whether VR and the legacy of Oculus will come anywhere close to Sega and Nintendo, but I did end up sinking my teeth into this story, spending three and a half years working on it. I think the earliest memory I have of it was–because this was such a big deal, that I had a book coming out, it was also a very big deal when someone wanted to write an article about me. I think the first publication to contact me was Popular Mechanics. They did a profile on me. It was such a big deal that my dad came to the photo shoot. Everyone in my family was super excited about it. The issue came out on Mother’s Day of 2014, so I slipped out of Mother’s Day brunch to get an issue of Popular Mechanics. I was so excited to finally see myself.

Before I even got to that point, though, I was so interested in what was on the cover, which was Palmer Luckey, the founder of Oculus, and this cover story about how his company had sold to Facebook for a few billion dollars. I was somewhat familiar with Oculus, but I never stopped to pay much attention to it. I thought it was a good sign when I was heading back to the restaurant and not giving my mom the issue with her son in it because I was captivated by the story about Oculus.

After that, I knew that I wanted to write a book about Oculus, or in the near future I suspected that would be something I’d like to do. But also, to tell the stories in the way I liked to tell them, it requires really credible access to the people involved. I want to be able to place readers in the room with them, on their shoulders, in their heads. It took me about 14 months from my first visit to Oculus to get permission from Oculus and Facebook to be introduced to anyone at the company and set up interviews. That finally happened in February 2016. This was one month before Oculus launched the Rift product, CB1. I felt like I was right there, on the precipice of something great.

My last book was a rise and fall story, and I thought this one was just going to be upward to the top of the world. That’s not how it turned out. I wouldn’t say this has been a rise and fall story, but I think anyone who’s interested in VR has been a little surprised by how it played out over the past few years. Also, the fact that the main character, one who appeared on the cover of Popular Mechanics and inspired my interest, he was no longer at the company within less than a year. It turned the book upside down. But as writers we go where the story takes us. I tried to follow that story when it went to places I never imagined I’d be writing about, particularly politics and crazy sub-Reddits.

Above: Oculus Quest fine print: “Neon circles not included.”

This book took three and a half years. This was three and a half years of me working full time on it. Console Wars took three years, but I had a day job for two of those. It was not the emotional investment that this one was. Because this one got into politics, and a lot of times politics I don’t agree with, it was pretty exhausting. I kind of can’t believe it’s finished. It was a running joke between me and my wife — or not a joke, because she didn’t find it funny at all — that I’d be done with the book in the next couple of weeks, because I said that every week or so for two and a half years. She deserves a huge award. I wish she were here. She got the dedication in this book. My mom was pretty upset about that, but Katie really deserved it.

The publisher didn’t sign up for this three-and-a-half year project either. They expected the book to be done in 18 months. For the most part they were supportive. There were some ups and downs. Because I didn’t turn it in on time — I ended up turning it in two years later — that was two years I wasn’t getting paid. My wife was wonderful enough to financially support me during that time. I’m glad she did. I’m glad I didn’t take the easy way out of just trying to finish the book for the sake of fulfilling a contract. I made sure to get to the bottom of the topics I was investigating.

Question: There was a post that went on your Reddit AMA where you mentioned that at a certain point, Facebook pulled access due to something they saw in one of the advance copies you sent them. Would you be able to talk about that?

Harris: Oh, yeah. It wasn’t an advance copy. In general, I’ve always tried to be very open and transparent and semi-collaborative with the people whose stories I’m writing, because I feel like they’re owed that much. Obviously that doesn’t mean they’ll have editorial approval over what I write, but I find that sharing with them–at worst they can give me feedback I disagree with. But often it spurs other ideas.

Early on, or I guess throughout the two years of my relationship with Facebook, we had a pretty good relationship. I shared materials with them and the people involved. When it came to the issue of Palmer Luckey, the founder of Oculus, and his not being at the company anymore–for those who are unfamiliar with him and his exit from Facebook, the short version is that in September 2016, he made a $10,000 donation to a pro-Trump organization. That organization’s goal was to put up billboards across the country, meme-like billboards, a very internet-inspired organization. Their objective had nothing to do with the internet, but the way the story was reported was that, essentially, Palmer and this group had been responsible for all the crazy shit you’d see on the internet, all the hateful, misogynist, anti-Semitic stuff from the past election season. That wasn’t true, but it certainly felt true, if you were on social media, because it kept being reported and referenced in articles reporting the same thing.

From that point on Palmer was basically sidelined at Oculus for six months, and then he exited the company. There were not too many details when that happened, in March 2017. I had come to know Palmer pretty well through where I was at this point in the project. I knew that it wasn’t his choice to leave. But initially Facebook declined to comment about what happened. Then, after I continued sharing material with them, I told them, frankly, my biggest concern with the book was Palmer’s exit and how to handle it. I couldn’t have one of the main characters in the book just disappear and say, “Whoops, that was the end.” I needed to provide some explanation.

Eventually I did get an explanation from a handful of people on a pretty senior level, people who could speak on behalf of the company. I came to believe that that explanation was fictional. They were going so far as to say that he chose to leave the company, which I would bet my life is not true. Some other details seemed to not add up. I started thinking about why they were telling me this and not just saying, “No comment,” or presenting a more plausible story. I was thinking that because of my narrative non-fiction writing style, which intentionally does not attribute specific information to sources, I felt like they were essentially trying to launder misinformation through that style.

I was hearing the same story from multiple people, having it confirmed. Palmer couldn’t talk to me, or wasn’t talking to me, I assume, because he was legally gagged from doing so. I felt I was being used to put this information out there. I ended up sending a chapter that was just a straight-up question and answer transcript with one of the people there, to see how they would react when their names were put on this material.

The conversation was on the record. The irony of the conversation I sent was that, in the conversation, I had asked this person if they felt that Palmer had been treated poorly by journalists who broke the news about him, because the conversation with the journalists had been off the record, and then this person said said, “No, no, it’s not off the record unless you specifically get a journalist to agree it’s off the record.” I thought that if there was any doubt about it, this was certainly not an off the record conversation.

After I shared that with them, the situation escalated to a whole different bunch of people who I had no relationship with. They asked me not to publish that. They gave me a different story about why Palmer was fired, having to do with bad performance reviews, which I also knew was not true. Also, around that time, the head of AR and VR at Oculus told all the employees not to speak with me anymore. That was pretty much the end of that relationship. I felt like I was lied to, and also I was no longer able to speak with employees. A lot of them continued to speak with me, of course, because they were not happy with the situation.

That was the other thing. I have no bone to pick with Facebook. I think it’s a free service that does a lot of good things. There are some harmful effects, in my opinion, but you can use it or not use it. I know some people, some journalists out there, think it’s an evil company that needs to be destroyed or something like that. That’s not my opinion at all. I was just shocked by how all this played out with Palmer. His experience seemed like a pretty good proxy for a lot of things going on in the digital landscape, from online mobs to politics in the workplace. I think what happened to him was unfair. At any company I would feel that way. I believe that if he had different politics he would still be at the company.

But the fact that this was happening at Facebook, a company that is–explicitly and internally, so much of their ethos is based on openness and transparency. I think that for the most part, they’re pretty sincere about it. I don’t think those are just empty words. But it did feel to me that when push came to shove, they were empty words. In particular, for Mark Zuckerberg, who has spoken — not too recently, but in the past — at length about privacy and believing that our digital lives and our personal lives are the same thing — he doesn’t seem like a big fan of privacy. He preaches openness and transparency. Yet he was the least open and least transparent one in this whole situation, going so far as to direct what Palmer would post about supporting a different political candidate than the one Palmer actually planned to vote for.

That was how the relationship came to an end. I think it’s unfortunate. So much of the book is a really positive, inspiring story, with ups and downs. There are some cautionary elements or debatable elements, like whether it was a good idea for Oculus to wait on the hand controller, the Touch controllers, until nine months after launch. I have my opinion, but ultimately it’s debatable. Whether they waited too long for the launch–they’re all good conversation points.

For anyone who’s already read the book, you probably felt the same way I did writing it. The last 100 pages are a completely different book, almost. I don’t think it had to be that way. It’s interesting that what Palmer seemed to experience, being lied to by the company and being pushed aside, was how I felt writing it. But I’m glad that I was the one in the position, and I’m glad, like I said earlier, that my wife was able to support me while I chose to try to get answers to that stuff, so I could make sure it was included in the book.

At the end of the day, the goal of getting into VR and AR is to own a piece, or have some role, in the metaverse, as it were, and to have a leadership role in shaping our virtual reality. I think the things that the company does in actual reality are very relevant to how they would govern in a virtual reality, what sort of things we might expect from the company.

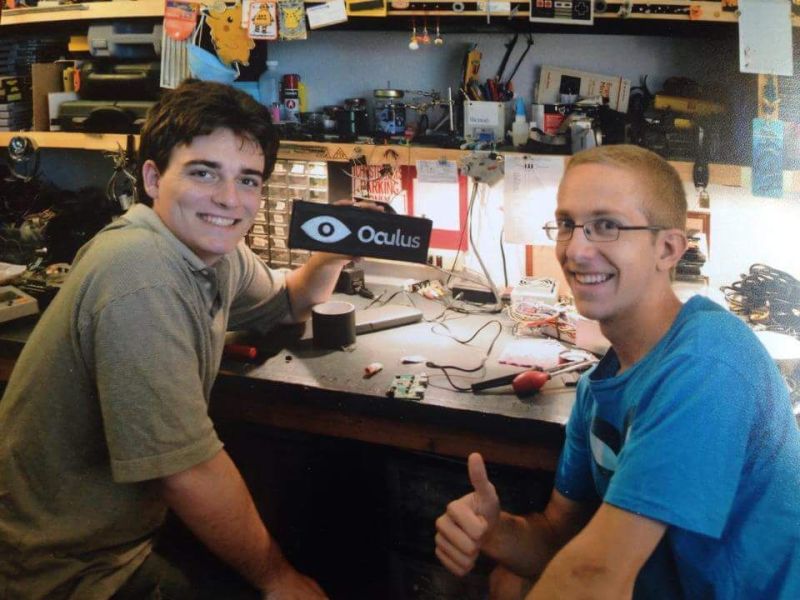

Above: Ross Martin and Palmer Luckey showing the first commercial Oculus Rift.

Question: Were you able to get Palmer to keep talking to you after this cutoff happened, or did you have to stop talking to him as well? Since it’s come out, have you gotten more reaction from Facebook?

Harris: Like I said, starting in February 2016, that was when my relationship and having access to people at Oculus began. This all took place between September 2016 and March 2017. During those six months, in which Palmer was forbidden to talk to his colleagues or to explain the situation, other than through the statement Mark had written and that he posted, I was talking to him. There were things he couldn’t say to me, but I do think that Facebook forgot I was–I mean, that I had a relationship with him.

He was careful about not talking about some of the stuff that happened that day. But when Gizmodo was doing Palmer Watch every day — where’s Palmer, we haven’t heard from him, he hasn’t been on social media — and people were wondering if he was being disappeared, I was talking to him every day. That was fascinating on a human level, to see someone who was no longer a daily part of something that they felt so connected to, and which they almost literally were the face of for an entire industry. Some of that is in the book. There’s a chapter about his exile.

After he exited the company–I assume one of the conditions was that he couldn’t tell me, that he had signed an NDA. But given our relationship it was pretty obvious. Unless he just suddenly became an asshole. [laughs] But no, he couldn’t talk to me about a lot of stuff. I still felt it was valuable to maintain the relationship, because like I said, I want to tell a character-driven story. Continuing to get to know him and how he thinks about certain things was helpful. The excuse to keep talking was to spend a lot of time talking about his new company, which is called Anduril. It’s a defense technology company.

In terms of the reaction from Facebook, I knew–I haven’t heard anything from people there in the past week or so, but I know that earlier in January, some employees were posting internally about the book, and they seemed to be excited. A manager calmed down their excitement, or curbed that enthusiasm, and said that–the response from management, in private conversations that I was told about, was that they didn’t know what was in the book, but they had heard that it was including manufactured drama, and was heavily focused on Palmer. Oh, and that they had worked with me early on, but then I broke trust with them.

I’m still not really sure what they mean by that, but they’ve said that a lot. There’s nothing in the book–the reason I knew they said this is because I got a lot of messages from people at the company who thanked me for keeping everything that was off the record off the record. I also just think it was significant in general that I knew what was being said. Maybe there was more I didn’t know about, but I think a lot of the people at the company, regardless of their political views, were not happy about how that whole situation played out, and felt a sense of distrust with the company. They were more willing to trust me, because I seemed to have more information.

They had the book for several weeks at that point. It’s not the worst kind of lie to say they hadn’t seen it yet, when they had. But just, wow, openness and transparency? And since the book came out, Facebook has done–it’s like a cut and paste operation for the past year. Every time there’s a negative story about them, they just say that not everything in the story is correct, without specifying what’s incorrect or providing any additional comment. It’s about what I expected. I guess we’ll see if there’s any more from there.

Question: The chapter “Nine Stories,” you could probably take that chapter and expand it into a book of its own, just based on the indie dev renaissance that sprang up as a result of Oculus. How did you distill all the stories from the indie scene down to those nine?

Harris: I don’t think I’m going to expand it out into a book, but if anyone were going to, I’d love to read that book. Or just write more about the indie dev experience. So much of what was wonderful about Oculus and the energy from the early days goes back to a decision that Brendan Uribe, the CEO and co-founder of the company, really helped to push, which was–Palmer’s initial vision for the Kickstarter, or for Oculus, was to get development kits out to other hardware enthusiasts and hackers like himself. By “kits” I mean actual put-it-together kits. Something I wouldn’t have known what to do with.

Brendan was really adamant that it needed to be a finished, complete kit. And then John Carmack was adamant even before that. I think Palmer was moving in that direction. But what was not initially the case was that–I make a comparison between Oculus and Ouya in the book, which was another potentially disruptive gaming system. They sold, for $99, a system that went to developers, but also consumers. That was their product. Early on Oculus made the decision that their customer was not going to be someone like me. It was going to be positioned exclusively for developers, with the goal of exactly what you’re describing, to have this sort of renaissance or this excitement and being a developer-focused company.

Above: Paul Bettner of Playful and Jeff Grubb of GamesBeat.

In that chapter I tried to pick people–it was hard. A had a list of about 20 people I could have picked. In most cases it was ones that either had a continued storyline throughout the book, or should have had, and will have in the paperback edition. I just never was able to include that. For example, one of them was Justin Moravetz, who did Proton Pulse. Part of it was because I loved his story of how, when he was in middle school, for a science project they had them build something of the future, and he built a homemade VR headset. I think that really helped capture the passion of a lot of these people. But at the same time he was working at Sony, and that was something I thought might be worth exploring.

Another thing I could mention, though at the end of the day I made the decision–I don’t mean this as an excuse. But the length of the book was always a big issue with my publisher. My first book was 550 pages, so of course I felt this one would be 550 pages too. They were thinking more like 300. I think it was a good victory to get to 500. Hopefully by the paperback it’ll get a bit larger still.

People have been sharing stories, either developers or other people on the periphery of the industry, since the book came out. I love all those stories. I almost was thinking I’d like to set up a webpage for people to put up their stories. Something where–I didn’t want it to come across like I’m trying to take possession of their stories. I just want there to be a place where you can read all these stories.

At the end of the day, as cool as the DK1 was, or the Rift, or whatever iteration, or even any other competitor product, it’s really hard to make money, because the ecosystem is just not big enough. Anyone working in this space is almost certainly doing so purely out of passion or experimentation. That’s the stuff I’d like to write about. I really felt like I could have written that about almost any developer who was taking that risk. I just wanted to try to pick ones that would line up with the bundled games in the Rift, or other things that I should have gotten to.

Question: Do you talk at all in the book about some of the competitors, like HTC and Valve or Magic Leap, what the whole ecosystem is doing?

Harris: Yeah, yeah. Console Wars is very much a corporate rivalry story. When I first started this, I think my actual pitch was, this is going to be a corporate rivalry story between Facebook and Microsoft with the HoloLens and Magic Leap and Valve and all these places. That was my perspective from the outside, having a console war mentality.

What I came to find when I got into the story, particularly the early years, was that it was such a collaborative process. As much as it can be between different companies who each, in the end, would like to beat each other. Valve, because of their role very early on with Oculus, and because a lot of the people there who were leading their small VR team, like Michael Abrash and Atman Binstock, ended up at Oculus, there’s a lot of focus on them in the earlier chapters. Not as rivals or competitors at that point, but just as a company with smart people who were curious about VR.

Later on in the book, there is not as much as one might expect there would be. For example, one of the chapters that was cut was just about Google’s VR project. I hope that will one day be returned to the book. But my thinking on a lot of this was, I wrote a book about stuff that happened 20 years ago. My first day of writing that, I knew what the beginning, middle, and end of the story were. It changed a lot from my outline, but I generally knew how it was headed. I knew what the pacing would be. This was a completely different beast, without even getting into Palmer Luckey.

Just as someone who constantly refreshed websites like UploadVR, who’s looking for every morsel of stuff that’s happening, there was a while where there were so many companies — the well-known ones like Magic Leap and Microsoft, and even the smaller ones doing games or middleware — because so much of it is passion-driven, it’s all appealing to me. For a while I had a Beautiful Mind sort of wall of all these companies and potential angles to go with. Maybe that would have worked as a book, but the more I thought about it, the more I factored in the unknown of it all. All too often these things are pitched as the big breakthrough, the next big thing, and I didn’t really feel like I could make reliable bets on whether that was accurate or not.

Above: Oculus Quest has no wires, so you can play tennis in VR without tripping.

I started to think a lot about the show Mad Men, which has always been one of my favorite inspirations. There’s a quote at the beginning of the book. If you were going to make a documentary about advertising agencies in the ‘60s, or tell a story about advertising agencies, you can go to different agencies and show different perspectives, or you can really just stick with Sterling Cooper and, through them, see a lot of what else was out there. The priority is still these characters and Sterling Cooper, so you’re not going to going to go out of your way and have a chapter on the Google VR project. But you’ll at least become familiar with it. That’s what I ended up opting to do.

Another–”challenge” maybe isn’t the right word, but another thing I thought about a lot–because this is a book about current events, and because I had a lot of information I thought would be newsworthy, there was maybe an approach to optimize the book toward getting out breaking news. For a while that was a direction I went in. Call me a romantic, but I like to think of good books as timeless. I wanted this to be a book like Console Wars that was still read five years later. I didn’t want to have to rely on these juicy morsels, or the perception that there would be information that you have to read now.

There’s a lot of other ways to get that out there. I could write an article. If I can’t dive into something I can share it with another journalist and see if they’re interested in it. I ended up really–the more the VR and AR ecosystem expanded, and expanded so quickly during what felt like the gold rush period, the more I stuck the scope of the book to focusing on Oculus and trying to see through the eyes of those core characters.

Above: Palmer Luckey (founder, left) of Oculus and Chris Dycus, employee No. 1.

Question: Palmer was very young when all of this happened. I’ve talked to him a couple of times. It’s clear that he was sort of astounded by it all. He was very much a kid. He talked about–when the deal with Facebook was consummated, he had more money to buy the juice that he liked. Things like that. Do you think that if all of that had happened 10 years later, if it’s the same sequence of events? Do you think he’ll be fundamentally the same person 10 years from now?

Harris: A lot of people like you, who I’ve been in touch with while writing the book, trying to pick your brain and share a little of what I’ve found–basically, I’m saying people who are open to the idea that what was reported was not fully accurate. The usual thought is, “Oh, Palmer’s just young, so it’s a stupid young person mistake.”

I think that because of what happened, and feeling like he was pushed out of his company the way it went, that did fundamentally change him. Even just looking at his new company, he’s much more careful about making sure to retain voting shares, to make sure he can’t get kicked out of the company. But as far as the starry-eyed lackadaisical approach, or almost just the childlike wonder, I think that hasn’t changed.

To me, one of the more significant conversations in the book is, after the Nimble America thing happens and it becomes a big deal and it’s reported that he’s funding this racist troll group or whatever–basically, after the worst comes out, true or not, he returns home from where he was during this period of time. He happened to be taking his first vacation since joining the company. He returns home to his four closest friends, his roommates, the people who had been with him since before Oculus, from his original message board–these people are as close to him as family, or probably closer from getting to know them over the years. Their question to him is, “What the hell?” And he jokes around at first, because that’s his way, but he doesn’t seem to show any contrition for what he did. In his mind–I think he referred to it as a “fun lark.”

On the one hand you could say he’s just not fully grasping the gravity of it, or that’s just how he thinks it should be, that people should think of it as a fun lark, even though a lot of people don’t. But I thought that was really significant, to have all those people in that conversation with him and to go through it all with them, go through the conversation so I could get it. It seemed like that would be a moment of pure honesty on his part.

I still talk to him almost every day, and I’ve never heard him say, “I shouldn’t have done that, or I should have done it in a different way.” His mentality is more like, “Why do people care about this?” There’s something to be said for that. But he’s also a smart guy. He should probably know that people are going to care about it, whether or not they “should.”

Above: Hayden Dingman at PCWorld testing out the Oculus Quest

Question: Do you still think VR is going to be as big a deal as everybody thought it would?

Harris: It’s something I’ve thought about a lot, now that I’ve had more time to think about the bigger picture and not focus on this story. Like a lot of people, even a lot of you in this room, my real interest in this book–Popular Mechanics got me interested in the story, but what made me want to spend years of my life working on this was my first VR experience, taking it off and literally just saying, “Wow, that was the future.” Then processing what that means, or how a company could monetize this, or what would be the business of it. Is this a platform? Is it a peripheral? What is happening here?

I preface with that to say that I still get that feeling a lot when I try VR. I don’t feel like I’m jaded by it. I’m still very frequently awed. But there’s also the reality of how things have gone over the past few years. You talked earlier about the chapter with the indie developers. A large part of my interest in that is because I find it beautiful that people would take such big risks for something they believe in, even if there’s not necessarily a financial goal or if it’s an unknown. At the same time, I did think it was significant that almost all of those people are no longer doing VR. Or at least Playful and Paul Bettner and company, who created Lucky’s Tale, and CCP, who created the other bundled game–I think it’s significant that those two companies, who were the first to jump in, the first to drink this Kool-Aid to be first for this thing that was going to make billions of dollars, they aren’t in VR anymore.

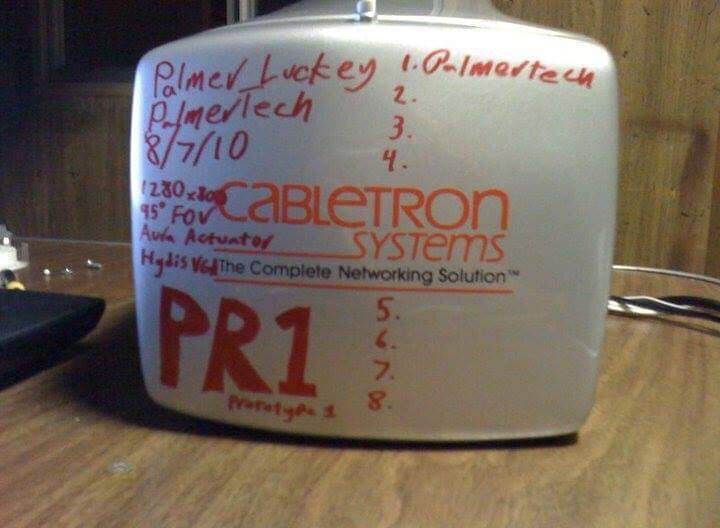

Above: Palmer Luckey’s first prototype of the Oculus VR headset.

It’s certainly not for a lack of passion. Or at least at Playful that’s the case. I haven’t spoken to the current team at CCP. There is this reality that we have to face, and I think that–I’ve been thinking more and more about something that Palmer told me, that I probably should have put into the book.

In an early conversation between him and Brendan, the CEO, Palmer has explicitly told me–he said, “I’m the person who started Oculus. Without me there would be no Oculus. But without Brendan it wouldn’t have been successful.” He credits Brendan for as much or even more of the success than himself. Very early on, during their first meeting actually, Brendan was talking about how big of a deal this is going to be, how this is going to change the world. Palmer felt the same way. He just felt it was going to take longer.

What I liked about that conversation was that Brendan, and very much how Mark Zuckerberg and a lot of other people have framed the expectations for VR–he saw it as a somewhat similar trajectory to smartphones and mobile computing. You go from Blackberry to iPhone, and within three to five years it’s ubiquitous, with millions and millions of phones. Palmer, at least back then — I’m not sure if he still feels the same way — he compared it to the PC revolution, where you had companies like Apple in the late ‘70s making PCs for more of a homebrew crowd. People were actually putting computers together, like Palmer’s original vision. It probably wouldn’t have gone anywhere. So you did need that hype and that excitement.

But I think that it’s looking more and more like, at best, it would be the PC evolution. In addition to it appealing to enthusiasts and people willing to brave the wild west era of the technology and the marketplace–if you look at how Apple excelled in the late ‘70s, you would say the PC revolution started then. But my family didn’t own a computer until the mid-’90s. That, to me, is when it became mainstream. That’s 15 years.

I don’t think this is going to take 15 years, if it happens at all, but what happened largely between the late ‘70s and when it got to my family was computers being used for business and enterprise purposes. That’s where we are seeing some strength for VR, whether it’s for training, for the military, for health care. I guess the short answer is I’m still as bullish and excited about VR as I was, but I don’t think it’s going to be something that my mom is going to buy, or call me up and ask how to use, in anywhere near the timetable I’d originally thought about.

Above: Author Blake Harris, writer of The History of the Future.

Question: When you were writing this, were you relying primarily on interviews, staying in New York to write and working through correspondence? Or did you try to get some first-hand accounts of what was going on? Did you got to Oculus Connect, to VR LA? Did you come out to California to get down on the ground?

Harris: Almost exclusively I relied on secondhand. In general I’m a homebody. I like to be removed from it. But I also realize that maybe that’s just an excuse because I’m a homebody. For a large portion of writing the book I had a really bad lower back issue. I was walking with a cane and not very mobile. That also contributed to why it took me so long.

But it is almost exclusively secondhand, and for that reason, my favorite compliments have been not from press, or excited readers even, but from people at Oculus in those early days saying, “You really captured it. It’s like you were there.” At least that makes me believe it can be done when you’re not there.