Virtual and augmented reality have had a rough few years: Pundits tried to proclaim VR “dead” despite growing consumer interest and sales, while AR’s high prices and limited utility relegated dozens of competing headsets into various “enterprise” niches. If you believed the naysayers, mixed reality was just a fad that should have been over by now.

CES 2020 proved the anti-VR and anti-AR crowds wrong — profoundly wrong, in my view. Walking through the North, Central, and South Halls of the Las Vegas Convention Center, I found mixed reality technologies all over the place, and not just from the expected players. Major automakers, peripheral developers, and streaming companies were all showing off VR- and AR-ready solutions, many of which were actually exciting. This show was easily the best VR and AR event I’ve attended, both because of and despite the fact that I had to walk miles in the real world to see the state of the art in mixed reality technologies.

Here are some of the most compelling VR and AR topics from this year’s CES.

Automotive VR and AR

The image above illustrates the broad sweep of VR at CES — this year wasn’t just about one headset in a booth, or one demo tucked away in a corner, but rather groups of people using mixed reality to “experience” new innovations for themselves. As one example, Hyundai used eight Pimax widescreen VR headsets to let booth visitors experience a ride in its S-A1 flying taxi, a real version of which was suspended in the air, as shown below. This was just one of quite a few VR experiences offered at CES 2020 by automakers, with a particularly solid use case for offering virtual rather than real experiences.

Above: While throngs of visitors gawked at a real, life-size version of Hyundai’s S-A1 flying taxi, eight people could use VR glasses to experience a flying Uber ride for themselves.

By comparison, what initially appeared to be a Honda VR autonomous driving simulator instead turned out to be a nine-minute story about the next 15 years of automotive advances, told with VR. Honda used cartoony but completely 3D VR to show off technologies such as “swarm” vehicle-to-vehicle traffic coordination in emergencies, and car windows that could serve as shopping displays or “soothing” views of the galaxy for passengers.

Lest that idea strike you as far-fetched, all it took was a brief walk to Audi’s “Intelligence Experience” to see the real thing in action, as the car’s windows were video screens. These displays weren’t gimmicks, either. Audi’s screens had AR icons pop up to indicate how a windshield heads-up display could flag live points of interest, electric charging stations, and the like as you drive. At one point, it recommended a breathing exercise for a passenger, seemingly based on health data.

Automakers were also using intriguing alternative display technologies to provide heads-up information to passengers. A separate Audi 3D mixed reality demo used left and right eye sensors to create a hovering stereoscopic display that only the driver could see; here, it was displaying a video, but in the real world it would likely be used for AR-style HUD purposes.

Many different approaches to glasses-free 3D displays were being shown off at CES, but that’s a big topic for another day. The value of such displays was particularly pronounced in the automotive world, where drivers shouldn’t need to wear glasses or goggles to enjoy the benefits of in-car AR.

Consumer and enterprise VR

Consumer VR has two standard-bearers at this point, Sony and Facebook, but neither used CES 2020 to make new product announcements. Sony instead touted its latest PlayStation VR milestone — 5 million units sold, more than any other tethered VR headset — while Facebook quietly enjoyed strong demand for the Oculus Quest, which largely sold out during the holiday season without the need for a price drop.

After generally unfavorable reviews for the HTC Vive Cosmos headset introduced at last year’s CES, HTC skipped this year’s show, which meant that none of the big consumer VR players had new hardware on hand this year. But there were other companies with interesting technologies to share.

Nolo showed off a 6DoF controller solution that could be added to existing smartphones, PCs, or headsets for $200, enabling SteamVR games to benefit from motion tracking with an accessory bundle. The accessories will work, the company notes, with 5G cloud VR games when they become more commonly available.

bHaptics showed off the Tactsuit line of wearable haptic accessories, including a $499 Tactot vest that makes you look like a SWAT team member when you strap a set of powerful vibrating actuators on your chest. I tried the system with PUBG, and saw it with music, and there’s no doubt that it brings strong sensations to your entire upper torso in a largely body size-agnostic design. The company is working on software-level support for an upcoming VR version of PUBG, which could be a big deal later this year. Update on January 17: bHaptics says that it “accidentally delivered incorrect information” regarding PUBG VR, which it doesn’t know to be “exact and true.” The company says that it’s pursuing software level integration with the current version of PUBG.

Enterprise VR looks like it’s in healthy shape, as well. Though I covered them in separate articles, Pimax and VRgineers both showed off impressively high-resolution “8K” (actually 4K per eye) VR headsets that are meant not just for enterprise users, but the most demanding customers — pilots and astronauts among them. While VRgineers boasted that its new 8K XTAL headset has already been purchased by the U.S. Air Force, I saw people from the Air Force evaluating Pimax’s Vision 8K X at the show.

While it’s impossible to capture a perfectly representative image through one lens, suffice it to say that both devices effectively eliminate the “screen door effect,” and only let you see individual pixels when foveated rendering — stronger central than peripheral detail — is turned on. Looking through both the XTAL (above) and Pimax (as rendered on a TV, below), there’s no doubt that even the most demanding enterprise and military users will be thrilled by the clarity of these new solutions.

Other VR companies are angling for a place in the enterprise, too. China’s Pico revealed Neo 2 headsets with and without Tobii eye tracking as lower-priced and potentially more versatile competitors to HTC’s Vive Pro and Vive Pro Eye.

And Panasonic showed prototypes of small, lightweight VR glasses (above) that appear destined for enterprise rather than consumer use, but may never advance beyond the concept stage. To achieve their size, the glasses use atypically small microdisplays that were shown as components at CES last year; they benefit from supposed HDR color rendition, but have a very limited field of view. Panasonic reps wouldn’t pin down many specifics, and I had the sense that the company hasn’t yet etched its plans in stone. We’ll have to see whether the concept actually becomes a product.

Consumer and enterprise AR

When people look back at CES 2020, they’ll remember it as the show when augmented reality had its first real consumer moment — the point when the technology stepped beyond the realms of sci-fi and $3,500 HoloLens headsets into mainstream affordability. Multiple companies were showing $500 to $600 AR glasses with various features, all intended for release before summer 2020. The critical factor that spurred this innovation was the use of a smartphone for core processing while loading lightweight glasses with sensors, cameras, and stereoscopic displays, an initiative Qualcomm has called “XR Viewers” or “XR Smart Viewers.”

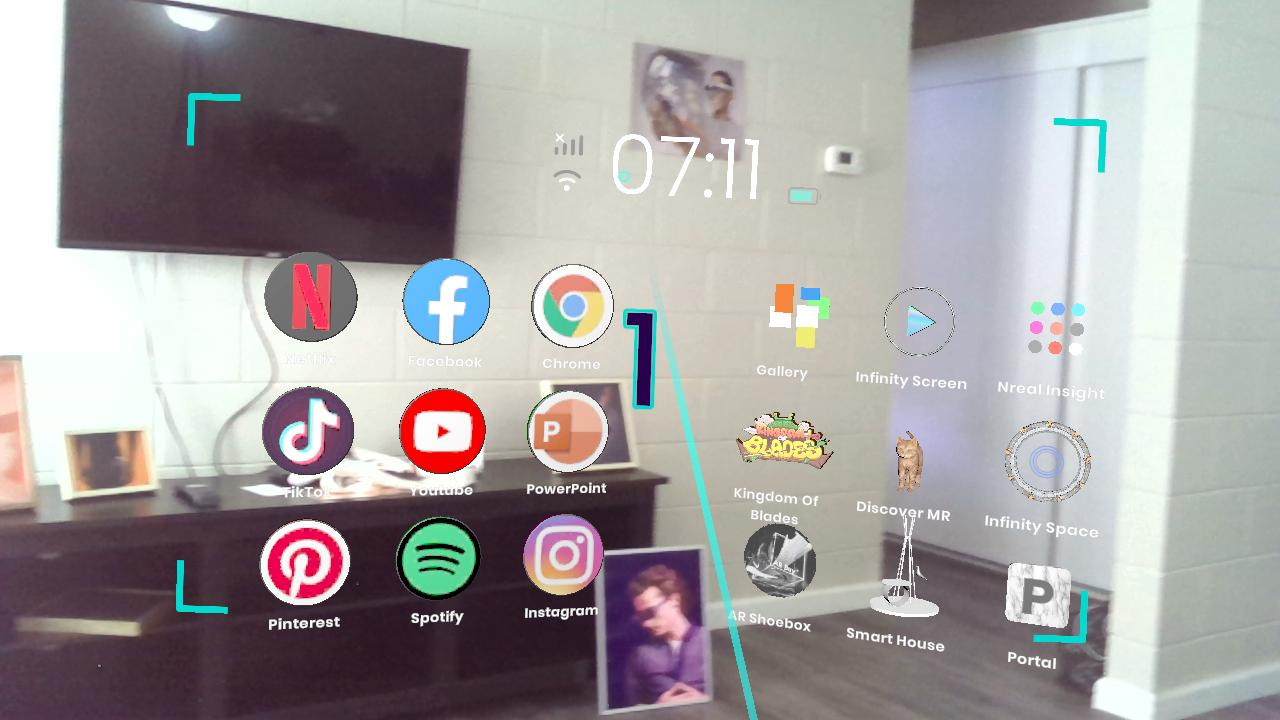

Without repeating myself by restating my positive impressions of Nreal’s Light AR glasses or Nebula 3D AR UI, I’m going to take a different tack here and share the bigger AR picture that emerged after I tested a whole bunch of new AR hardware at this year’s show. The TL;DR version: AR has come a very long way since last year’s CES, but I’m still on the fence about how mainstream it will be by next year’s show.

Above: Nreal’s Light AR glasses have established a design and performance paradigm other companies are already trying to match.

Nreal Light is the best of a growing pack of consumer AR solutions that, as of now, appear mainly to be coming from Chinese companies. There’s Nreal, and then there’s everything else — glasses that range from “similar ideas” at best to knockoffs at worse, none with the combination of design, comfort, visual performance, and software support Light brings to the table. After trying similar-looking glasses from MadGaze, 0Glasses, and others, it’s clear that there will be no shortage of fairly lightweight AR glasses in the marketplace this year, but Nreal’s will stand above the rest.

Above: 0Glasses’ RealX apes Nreal Light’s look, but not the experience.

Show floor buzz from multiple companies in the consumer AR space is that Apple is unlikely to enter the market this year, and may well be two years behind the early market entrants. This isn’t a huge surprise given the multiple reports of challenges and delays in Apple AR development, but it gives earlier entrants an extended opportunity to win fans — and influence broad consumer perception of AR — while Apple waits for the near-perfect combination of technologies and design to become feasible for mass production.

My chief personal concern at this stage about the consumer AR glasses I’ve tested is somewhat unexpected but critical: fit. In most of the glasses I tested at CES, the optical systems were projecting on an angle that works fine for noses that sit lower on the face, but if the bridge of your nose is higher, you may have to tilt the glasses unnaturally to see the “augmented” area. Then, it may appear to be too high or low, and if the glasses have an interior camera for gaze tracking, it might not be able to see your eyes correctly.

VR systems have been challenged to get the right horizontal IPD (interpupillary distance) to match displays to the varying distances between eye pupils. AR glasses now appear to be contending with a vertical positioning challenge as well, to say nothing of the need for flexible frames to match larger head sizes, cable positioning and weight considerations, and so on.

Above: The Nebula interface looks like a home screen from the front, but each of the icons and text elements is actually 3D and can be viewed from any angle as you walk around.

My secondary concern is the performance of AR glasses’ room-scale tracking systems. When these glasses can properly map a room, like Oculus Quest can for VR, their interfaces can do a remarkable job of displaying location-persistent content. When I tested Nreal Light’s Nebula system, for instance, I was able to physically walk behind the “home screen” interface full of icons and text to see their (nice-looking!) back designs. But it remains to be seen whether the shipping version of the room-mapping feature will actually work as well as Quest’s, or fall short.

Above: MadGaze was using a hand-tracking rhythm game to show off Glow Plus AR glasses, but the tracking feature didn’t work well at all when I tried it.

AR companies are also working through input solutions. Nreal is open about the fact that it’s experimenting with virtually every available option — its consumer glasses will have the ability to use a smartphone as a 3DoF input akin to a laser pointer, rely on head-mounted cameras for eye and hand tracking, and/or work with third-party 6DoF arm sensors (below) and controllers. Other AR glasses developers appear to be focusing on one or two input options, rarely with great results.

I didn’t spend much time with enterprise AR solutions at CES, largely because the jump from last year’s to this year’s devices didn’t seem profound, and the best-known enterprise AR players — Microsoft and Magic Leap — weren’t exhibiting on the show floor. At least in the (many) spaces I visited, I didn’t see any HoloLens or Magic Leap One hardware in use at booths, a change from last year when at least a couple of prominent companies offered demos using those devices.

More common were companies such as Vuzix, which used CES to announce M4000, an enterprise AR headset similar to its earlier M400, but now with a completely see-through (and more expensive) optical waveguide display. The pitch is that M4000 will provide specific industries with a visually less intrusive AR viewing option, while M400 will continue to serve most of its enterprise customers’ needs.

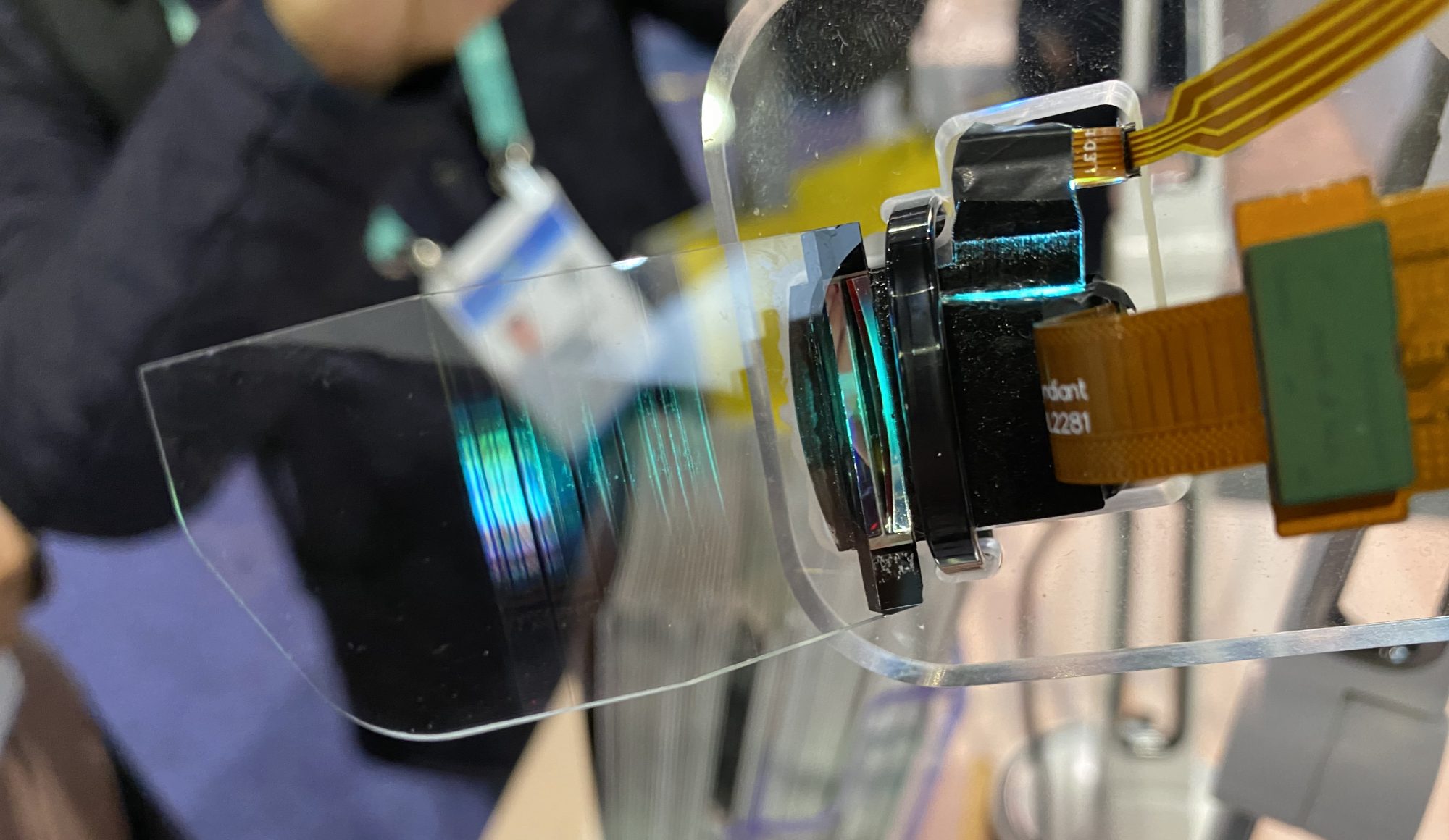

Above: Syndiant’s waveguide displays use side-mounted projectors to channel beams of light into lenses. At the right angle and distance, those lines turn into a video image.

Since waveguide is considered within the industry to be the display technology of choice for future AR solutions, I asked display maker Syndiant about the pricing and performance differences we can expect to see this year. Waveguide displays start at price levels 15-20% higher than non-waveguide screens, the company spokesperson said, but to get waveguides with equivalent or superior resolution and detail, say nothing of multiple planes of depth, the cost could jump to a 50% or 100% premium. In other words, don’t expect waveguides in consumer AR headsets too soon.

Summing it all up

Since CES is an industry-only event — and a gigantic one that any person will struggle to see in full — I can’t suggest that you rush over to Las Vegas to see all the AR and VR innovations for yourself before it ends this week. But this year’s show is truly a great exhibition for mixed reality, regardless of whether you’re interested in consumer or enterprise markets, AR or VR, and glasses-based or glasses-free displays.

It really feels as if AR’s hardware, software, and overall user experience elements are beginning to show the polish they’ll need to achieve mainstream use in the foreseeable future. VR’s gradual expansion from consumer devices into retail and business use is actually becoming compelling as well. So if CES 2020 is any indication, this is going to be a really exciting year for mixed reality, and I’m looking forward to seeing what happens in the months to come.