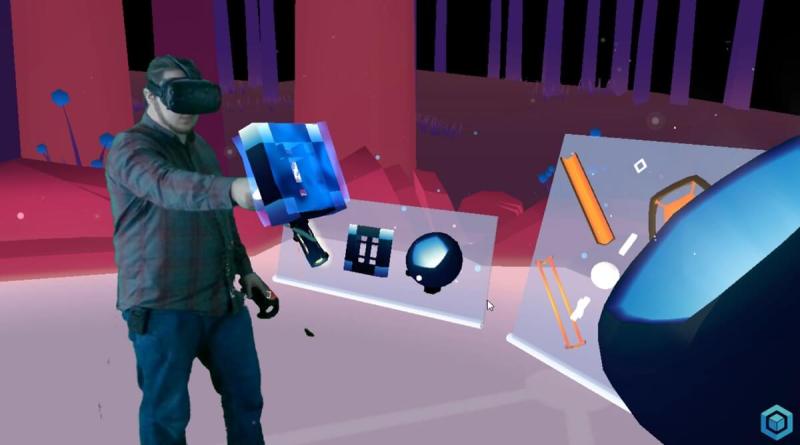

Above: MixCast VR.

We’ve done a couple of film collaborations with independent filmmakers. One was about sustainability and the Amazon rain forest, called Tree. It has every sense available to you — sight, sound, smell, haptics — so you feel like you’re a tree in the Amazon. You’re growing and growing. I’m not going to spoil the ending, but it’s about protecting that forest, so you might imagine what happens to you. But again, it’s a really good story and a way to raise awareness.

Another creator in particular is Eliza McNitt, who’s an Intel Science Fair winner. She’s created a couple of films. Her first one is called Fistful of Stars, placing you in the middle of a galaxy. We’re working on a new one with her called Pale Blue Dot, which is focused on Earth. In addition to gaming, there commercial and educational applications, and I think film is only just getting started. There are categories at Sundance and all the other festivals now, so we’re beginning to see what might happen there.

One last area on the content front is the stuff the Intel Sports Group is doing. We have a whole division at Intel now focused on what they call the digitization of sports. It’s the way that, when people watch football or baseball, it’s all being digitized in some way or another to let them engage with it more. That’s a very big domain, but a portion of what they’re doing involves how you view it and consume it in VR in different ways.

They have an effort going where we acquired Voke. They’ve turned that into the TrueVR technology, where they’re streaming 360 sports content, but you can switch between different camera points in the stadium. “I want to be court side. I want to back up and view from behind the net.” That’s not being created just to propagate VR, but VR is an obvious target for it. It’s real content that Intel is involved in developing and technology we’re taking to different partners that will end up being one of the things on the list of what you can do in [your] Microsoft headset or your Vive.

GamesBeat: Where is that available right now?

Pallister: Right now it’s Gear VR. We’re working with them on getting it to some flavor of PC VR. It’s really just that. They’re almost a startup within Intel. It’s not a question of whether we want to do it but just in what order we want to do it.

Above: MixCast VR.

GamesBeat: What’s the difference between the system we’re seeing here on the Vive and DisplayLink’s XR?

Pallister: This is using the DisplayLink codec, but the implementation here is built on top of Intel’s WiGig technology. Chances are, if you saw DisplayLink demoing something — they can build their stuff on top of other transports, but the best version right now is on top of WiGig, so they’re probably demoing stuff on top of that. Think of one as the transport layer and the other is the compression and communications layer. We built the prototype together with them.

GamesBeat: Are you just using their algorithms to encode and decode, or is it a chip?

Pallister: It’s a piece of silicon, and they’re doing that. It’s an algorithm, but it has to run at such a fast rate that it wouldn’t be power-efficient to take a general-purpose processor and run it in software there. The best power efficiency is building it into hardware. They could opt to go take a product to market, but what we collaborated with them and HTC on — HTC wants to go build, and has said they will build, an add-on for the Vive based on that combination of technologies. Our belief is that ultimately, the best solution is going to come if HTC takes it and integrates it with their product. Even as an add-on module, it’s all built to work together smoothly. It really should come out of their shop.

GamesBeat: What’s the timeline and the economics of WiGig? How fast does this become a low-cost solution?

Pallister: There are two pieces to that. As to how well it gets integrated into the product and what it’s going to cost, that’s an HTC question. Obviously, if they do a future version of the Vive, and they integrate it directly into the headset, there will be a lot of cost savings there. But it’s their call. The way we’ve spoken to them about making it work with PCs out there — right now, not many gaming PCs have WiGig built in. It has to be a PCI-E card or a Thunderbolt module or something like that. Eventually, that’ll get to where people ship WiGig in the platform, and that’ll lower cost. You could see an OEM saying they’ll do a bundle and build a gaming rig for WiGig that has this thing in it.

Above: HP’s VR headset and backpack with attached laptop.

GamesBeat: How long a process was it to figure out that wireless to PC was the better way to go versus a stand-alone headset? Is that the last year or so?

Pallister: I’ll toot my own horn and say I knew three years ago. [Laughs] Or I believed. Let’s put it that way. There’s a lot of factors in there. Some people didn’t think we could pull off a wireless solution. Some people thought a large number of customers wanted a platform that was exclusively VR, a VR Wii if you want to think of it that way. It was a continual point of debate, so we had efforts focused on both possible outcomes.

Then, it was over the past six months, eight months — even at CES last year, we were showing WiGig behind closed doors. It was becoming apparent that we could do a decent job there. We really have no compromises. The performance you can deliver from a 500-watt desktop that plugs into a wall outlet — no way you can get that kind of experience out of anything you wear on your head.

GamesBeat: It seems like WiGig might also usher in a lot of other things that should be wireless. We’re already getting to wireless keyboards and mice. I don’t know if wireless monitors or TV connections are coming.

Pallister: There are a bunch of things like that. The infrastructure is laid down for those who know how to do it. The challenge there is that — in the VR case, the implementation of WiGig was really aimed at VR. Latency is king. Resolution is second. Other things are third and fourth. You could do a solution for, say, wireless displays for gaming, taking the same approach. But a lot of what drove these things were other use cases where the priority was different.

To take the wireless display example, a lot of the first implementations — the primary use case was, “I want to walk into my conference room and not plug in anything and put my report on the screen. I don’t care about latency, but the text had better be readable, and it needs to always be compatible.” That set of priorities results into something that you then have to repurpose for gaming because as it is, it’s not so good. Over time, though, absolutely.