Investors, gamers, and game developers who are cold on virtual reality should look to the 2017 Game Developers Conference as confirmation that VR has legs. Developers don’t sound as clueless as they did last year, based on attendance at VR-related panels at GDC 2016 and GDC 2017. The difference is palpable.

The fate of virtual reality does not rest on the development of more advanced optics, higher framerates, and lower latencies, nor does it depend on the evolution of the three major VR hardware solutions, the HTC Vive, PlayStation VR, and Oculus Rift. The hardware is not what will ultimately determine whether investors in VR make the profits they’re seeking, and whether futurists see the day when VR is an ordinary, household technology.

Because the success or failure of VR is much more in the hands of the game developers providing content for all three platforms.

Consumer VR still rests mostly within the video game world, and so the platform is subject to the popular refrain among gamers when it comes to any new hardware: “But there’s nothing to play for the system!” (We’re seeing the same discussion play out right now in reference to the newly released Nintendo Switch.)

A growing comprehension of the psychology of virtual reality, or how we can fool the human brain into believing that the virtual is actually the real, combined with technical acumen has finally produced a healthy slate of games for VR. Burgeoning mastery of the VR space has made critical successes like Fantastic Contraption (from Northway Games), Job Simulator (from Owlchemy Labs), and Raw Data (from Survios) possible.

These are the games from which VR developers can learn best practices. The fate of virtual reality depends on how quickly developers can learn and apply those lessons, and continue to release software compelling enough to warrant early adoption of the technology. Taken collectively, the VR-related panels at GDC 2017 suggest that developers are on the case, and the future of VR feels less nebulous as a result.

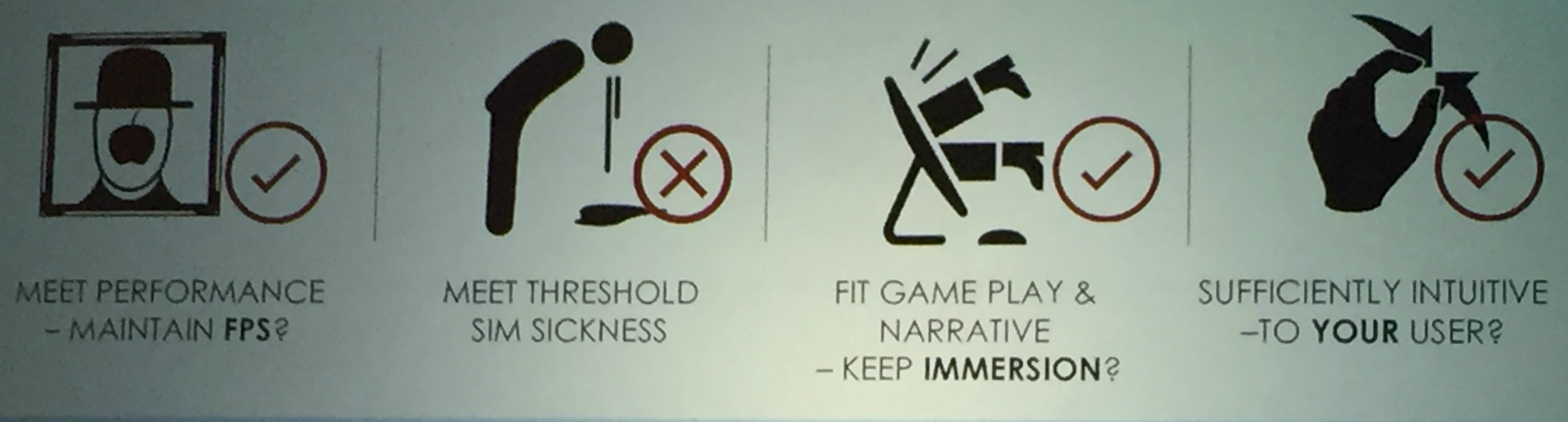

Above: Above: The basics of successful VR design.

From then to now

Wind the clock back one year. Virtual reality was a sensation at the 2016 Game Developers Conference. Panels scheduled in smaller rooms were choked with attendees. Sometimes, even spillover rooms with remote video feeds of the panels were standing-room only. Attendance at VR panels on the Monday of GDC 2016 forced organizers to move Tuesday’s panels into larger rooms in order to accommodate demand.

Because none of the major hardware solutions had yet been released at that time, game developers at GDC 2016 could still project their own hopes and ideas onto VR. Game developers working in VR didn’t entirely know what they were doing. It was the same feeling that pervaded the Oculus Connect 2 conference in September 2015, and VR developers at GDC 2016 didn’t seem to be bothered by this. The excitement of pioneering a new technology was enough to override all other concerns, it seemed.

Virtual reality panels at GDC 2017, on the other hand replaced fantasies of what VR could be with the reality of where the industry currently stands. Gear VR sales stand at either 4.5 million or 5 million headsets sold-through, depending on whether you listen to market research firm SuperData or Samsung Electronics America respectively. Sony in February revealed that PSVR has sold-through over 900,000 headsets.

Oculus and Vive sales are anemic by comparison. SuperData in February also released data that indicated “more than 400,000” Vive units had been sold, beating out the Oculus Rift, which sold a little over 200,000, according to the report. But the high barrier of entry to the Vive and Oculus, if we include the cost of a gaming PC that can handle the hardware, ought to make those numbers unsurprising.

These numbers represent neither failure nor success from any objective measure, especially not when insiders like John Riccitiello, CEO of Unity Technologies, don’t expect VR to start turning the sort of profits bullish developers and investors were hoping for any sooner than 2018. In the face of three relatively low-profile VR hardware releases in 2016, coupled with the lack of high-profile successes in VR, it’s no surprise that developer interest seems to have cooled, judging by panel attendance at GDC 2017.

The information conveyed in those panels, however, demonstrated how quickly VR developers are coming to grips with the hardware.

Above: You have about three seconds to disarm that bomb. Good luck!

Even the best VR devs are still learning

Games like Fantastic Contraption, Job Simulator, and The Lab are some of the highest-profile examples of successful, fun VR design we could point to. One might imagine that the developers of these games have therefore attained some level of mastery over VR. It might be more accurate, however, to say that successful VR developers are the ones who continue to ask the right questions about how the technology works at a psychological level.

Jesse Schell is the founder of Schell Games, the developer behind one of the earliest high-profile VR games, I Expect You To Die. Schell and his team had an advantage: Schell has been working with VR for 25 years, going back to his time creating VR experiences for Disney theme parks as an Imagineer. Schell also teaches a course at Carnegie Mellon University called “Building Virtual Worlds,” where every two weeks, a cross-disciplinary group of designers and programmers builds something unique. This often involves VR.

“So, another thing that I learned out of [Building Virtual Worlds] is the notion of getting up close, in VR,” said Schell at his panel entitled “Lessons Learned from a Thousand Virtual Worlds.” “A lot of people don’t realize that the brain has special nuclei for dealing with situations where physical objects come within arm’s reach. There are certain parts of your brain that turn on when that happens. Other media are not able to turn that on, but VR is able to turn that on.”

Schell delivered a prime example of how developers are understanding what makes for compelling VR experiences, by understanding the related psychology that powers those experiences. Comprehending how VR does what it does to the human brain is not just an interesting aside for developers. It may be a prerequisite for success. “We made strong use of that in I Expect You To Die,” said Schell. “We’re making use of it in all of our VR games.”

Proprioception, or the mind’s ability to sense the relative placement of parts of the human body (like being able to tell whether your arm is being held straight up over your head or extended out away from your body), is another sense that VR developers are learning how to manipulate. If you’re playing a VR game with a control pad, your hands are in relatively the same position during the entire experience, so proprioception isn’t involved.

When hand units like SteamVR controllers or Oculus Touch are being used, and the player is changing the shape of their arms as they reach around the simulation, proprioception becomes a factor. As long as the position of the player’s body parts in VR matches the relative position of the player’s parts in the real world, the brain accepts the illusion of reality.

When the vestibular system that affects our balance doesn’t match up with what a player is seeing in VR, that’s a surefire way to make the user motion sick, so developers have learned not to tilt the horizon, in VR experiences. The human brain is not always a liability that VR developers have to account for. Sometimes, the human brain is a tool that VR developers can use to create smoother, better experiences.

The idea of the “snap turn,” for instance, a practically instantaneous camera movement to a different angle from which the player had been seeing, triggered by pressing a control stick left or right. It’s a form of movement that may be foreign to the brain, but it works because the brain doesn’t have time to process the weirdness of a snap turn. It happens too fast.

Chris Pruett, head of developer relations at Oculus, explained how the trick works at his GDC 2017 panel “Lessons Learned from the Front Lines.” “Snap turns are a form of a sort of more general rule which is called change blindness,” Pruett said. “Change blindness is the idea that if you don’t show the brain something, and it changes … I didn’t see it, so I buy it.”

This is why snap turns, and the popular point-and-teleport movement option in VR, most often referred to by developers as “blinking,” don’t make users motion sick. The movement happens too quickly for the brain to register the change, hence the brain accepts the user’s new position in the virtual space.

These learnings are the basis for successful VR software development. If we did not hear game developers talking about the fundamental rules of successful VR design one year after the release of the Rift and the Vive, we might have cause to worry if we care about the future of VR. That game developers are understanding the rules and limitations of VR so clearly, and so quickly, is a ray of hope for anyone who wants to see VR succeed.

Above: Office work is fun, if it’s only for pretend, and takes place in 2050.

One possible explanation for why VR panels at GDC 2017 were less full than last year was the Virtual Reality Developers Conference held as a standalone event in November of 2016. I asked Alex Schwartz, founder of Owlchemy Labs, and a member of the VRDC advisory board, whether the event in November may have stolen some of the thunder from GDC 2017.

“VR is still so incredibly new and there is so much to discuss, try, share, and learn,” Schwartz told GamesBeat via email. “There are a surprising amount of VR conferences already, and I think developers are still trying to figure out the best format for sharing information. GDC every year is fantastic, but we’re finding that smaller more specific conferences can be useful to get deeper into certain topics. We’re working with a new technology so there is a TON of ground still to cover.”

According to Schwartz, when the VRDC advisory panel sat down to decide what panels to host at GDC 2017, disseminating practical information was the goal. “Everyone agreed that we need less speculation on ‘what’s possible’ and more postmortems and lessons learned from people who have actually shipped content/tech in VR,” said Schwartz. “People are still learning how VR works as a medium, including specifics of narrative, design, and mechanics that are keyed to the technology, and it’s definitely best to hear both the successes (and failures!) from people who went through the gauntlet.”

For VR developers who have worked with the technology for decades, hearing these conversations at GDC 2017 sometimes felt like watching the youngsters catching up with the adults. “This is the first grown-up conversation I’ve heard,” said Andrew Prell, following a Monday afternoon panel titled “Teleportation and locomotion from the trenches: What movement is right for you…” about the different ways VR developers can move players around virtual spaces without making the players ill.

In the late 1990s, Prell took the first-person shooter Wolfenstein 3D, created a VR version of the game appropriately titled Wolfenstein VR and sold it as an arcade experience. For Prell, many of the questions VR developers were grappling with at GDC 2017 have long since been answered. “SIGGRAPH [an annual meeting of experts in computer graphics and interactive techniques] in the early ‘90s was like a VR meeting,” Prell said.

Grown-up conversations about VR, for Prell, are not about developers’ dreams as to what VR could or should be. They concern what developers did, what worked, what didn’t, and why. Viewed from that perspective, GDC 2017 played host to some of the most “grown-up” conversations about VR that the game industry has been privy to thus far.

They’re conversations that need to happen. As stated by Carrie Witt, lead artist at Owlchemy Labs, during the GDC 2017 panel simply titled “The Art of VR,” effective techniques for PC and console design don’t necessarily work for VR, and in some cases opposite wisdom from traditional positions may apply.

“For Job Simulator,” said Witt, “sometimes we had the problem of making objects that you interact with too close to real life, and a really good way of simplifying them for VR was looking at Fisher-Price toys.” The idea of deliberately abandoning realism would be anathema for core gamers looking for developers to tap into the power of the Unreal Engine, for example, and create the slickest and fastest graphics possible.

VR games like Raw Data that stress Unreal-level graphics might only be able to run at the lowest settings possible on some VR-ready PCs. Raw Data made $1M in one month, and thus demonstrated the market for “core” VR content, but it does not represent the way most VR developers are approaching their games.

“Believability is more important than fidelity,” Witt later told GamesBeat. Job Simulator may feature cartoon hands, but 1:1 hand tracking makes the hands feel believable anyway. And while Job Simulator as a whole may look like a cartoon the level of interactivity allows Job Simulator to fool the brain into thinking the game world is real, even if it is a cartoon. Again, VR developers know how to use psychology to their advantage in order to craft the compelling experiences that justify the value of VR to the consumer. It provides experiences that you cannot get anywhere else.

Above: VR developers face challenges that no developer has ever faced before. Every first step potentially sets a new standard.

GDC 2017 did not paint an entirely-rosy picture of the VR industry. Nelson Rodriguez, the director of games industry marketing at Akamai, in a panel titled “Dear VR, where’s my money?” pointed out that some VR developers are being sheltered from the vagaries of the marketplace via support from platform holders.

“Subsidized game development,” said Rodriguez, “which seems to be in the several-hundred-million-dollar range right now. … There’s a subsidization model which, I think we’re still in that space. We’re still at that time, right?”

“I don’t think that’s a business model, I think that’s a funding model,” replied Mihir Shah, co-founder of Immersv, Inc., a mobile virtual reality advertising network. “That’s a way to get funded which is non-dilutive and it’s a great way to do it, but it’s not a business model. You can’t do that forever.”

Raph Koster, one of the foremost experts in the video game industry on MMO design, in a panel titled “Still logged in: What AR and VR can learn from MMOs” described the unique challenges that designers of VR social spaces will have to face. In a traditional MMO, for example, moderators can review chat logs in the face of harassment accusations. Virtual reality social spaces will likely have players communicating via voice chat, so this tried-and-true method of policing MMO populations won’t work.

How do the developers of VR worlds handle harassment complaints without impartial evidence to review? “If you don’t have tools like this,” said Koster, “you are literally going to spend your entire monthly profit on the first call [from a player with a complaint], standing there mediating between two people who are yelling at one another.” Should hand gestures be recorded for this purpose, so that moderators can investigate obscene gestures that one player might make towards another, and weigh the degree to which said gesture sparked a confrontation?

Developers expressed concerns over whether VR experiences are currently accessible enough for all sorts of players, and shared the results of research into what kinds of VR content are preferred by senior citizens. Educators hosted panels that laid out road maps for the best way to teach VR to students and provide a steady flow of new talent, without which the commercial VR industry may not survive.

Cynics might point to these challenges as further evidence that the odds are mounted against the success of VR, but that’s the wrong lesson to take away. One year ago, VR developers were all but holding their hands up and admitting ignorance. This year VR developers can afford to think about these more subtle challenges, because it seems as though VR is not going to be just a flash in the pan, and the developers working in the space can afford to think about the future in different ways than ever before.

At this point, especially after the 2017 Game Developers Conference, smart money might bet on VR being here to stay, and early adopters and investors should feel more confident than ever that their attention and money were not being wasted.