testsetset

Though I only occasionally write about augmented reality, I sift through plenty of “news” these days that is kinda-sorta AR, but not really. For example, if you believe that a TV show is using “augmented reality” to superimpose weather graphics on the screen next to a live meteorologist, AR has been commercially available for decades. Video compositing and computer graphics have become dramatically more realistic and easier for presenters to use, but I wouldn’t call this augmented reality — at best, it’s augmented video. Similarly, as Instagram, Pokémon Go, and Snapchat overlay cartoony graphics on top of a live video feed from your phone’s front or rear camera, they’re augmenting your personal reality, just not convincingly.

I would love to differentiate the concepts of true- and quasi-AR by using some nice terms like “Hard AR” and “Soft AR,” but those phrases are already taken. Seven years ago, Oculus chief scientist Michael Abrash was working for Valve, where he said his team distinguished Hard AR as wearable lenses that perfectly intermixed digital and real content that a group could share, versus Soft AR, which had noticeable imperfections, such as ghostlike rather than solid digital imagery. “Hard AR is tremendously compelling,” he said, “and will someday be the end state and apex of AR. But it’s not going to happen any time soon.”

Abrash was correct: Many years later, Facebook’s Oculus unit is still talking about developing the underlying technologies for a hard AR solution, rather than actually manufacturing AR devices. The dream, Facebook said this week, is a pair of “all-day wearable AR glasses that are spatially aware.” Before that happens, it noted, Oculus Insight spatial AI will have to shrink to 2% of its current energy requirements, and benefit from related hardware manufacturing innovations. In other words, don’t expect to see finished consumer AR glasses at Oculus Connect 6 next month.

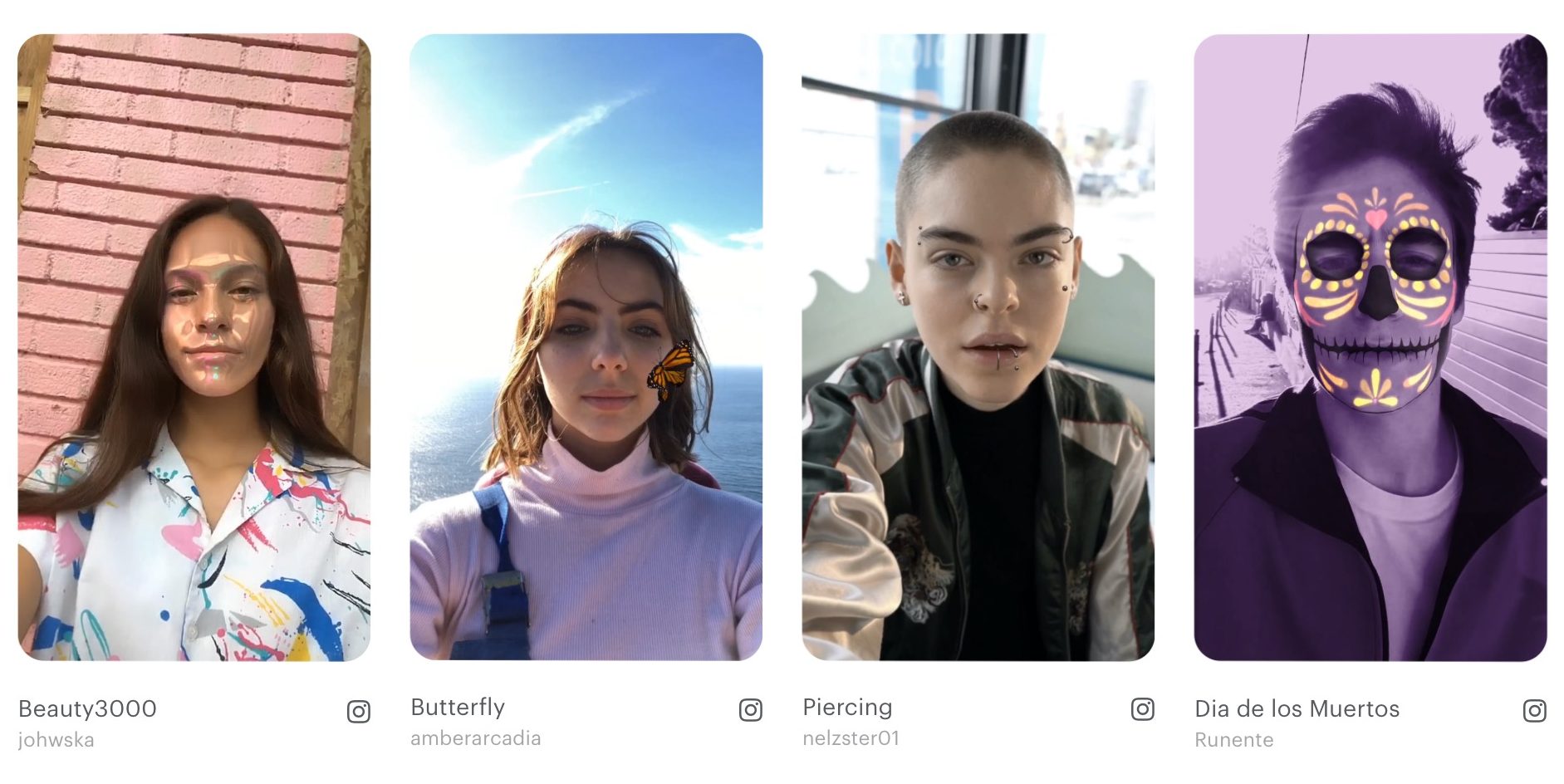

So engineers at major technology companies know what AR will eventually look like, and keep taking small steps that move closer towards or approximate the technology along the way. On the hardware side, HoloLens and Magic Leap One fall short largely because they’re ghostly and have poor fields of augmented view. Apple, Google, and their app makers sidestepped the lack of AR headset technology by using smartphone screens to show ARKit and ARCore content. Until shareable, persistent AR assets become more common within the real world, the results will mostly be quasi-AR apps that put cartoony animal features on your face, stars behind your head, and text banners on backgrounds.

Above: Facebook’s Spark AR Studio.

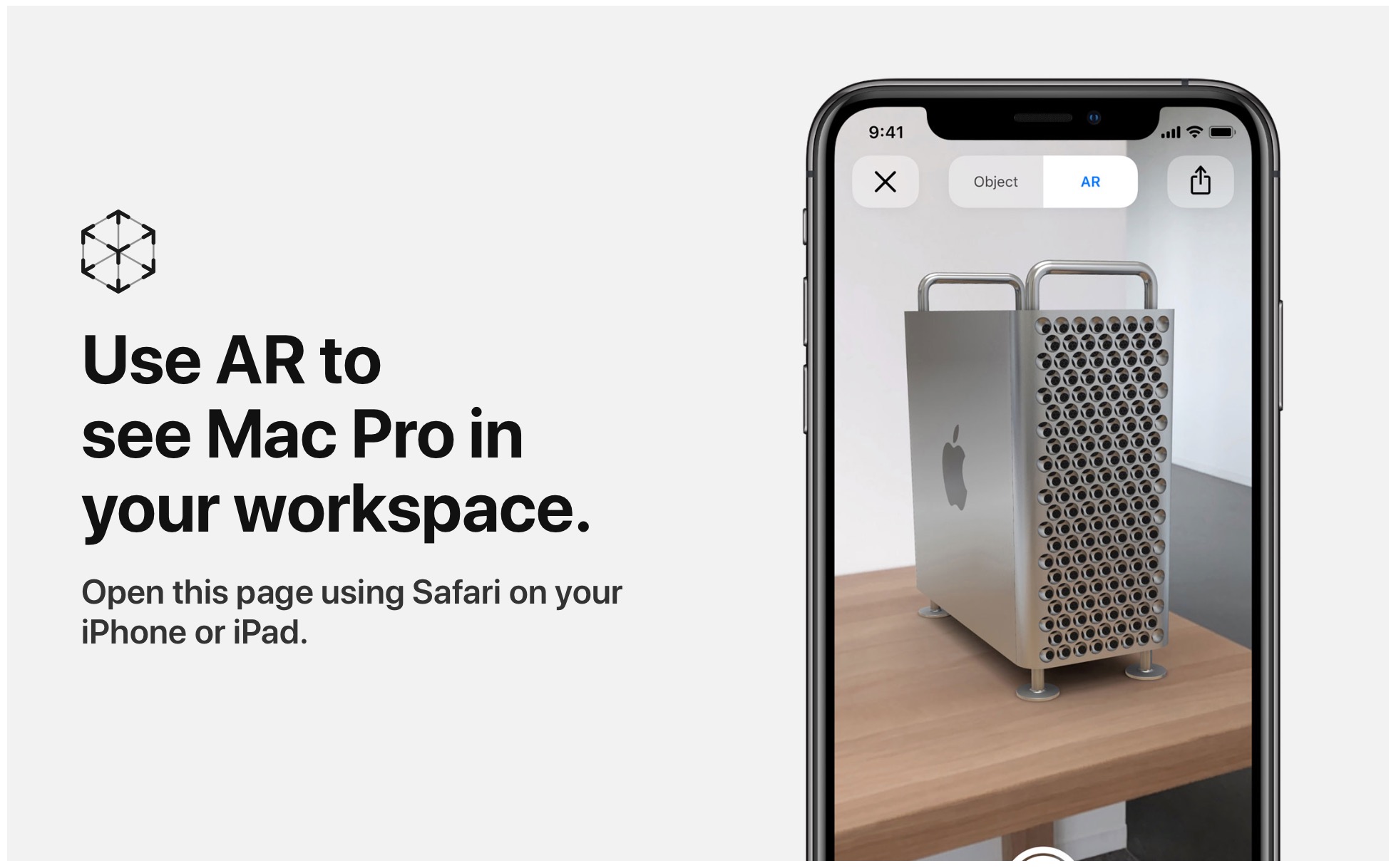

This isn’t to say that these baby steps are bad. Marketers are increasingly finding this quasi-AR useful in convincing people that couches will look right in their living rooms or that computers will fit on their office desks. They’re also letting people try on shoes and shirts without actually soiling real clothing and giving people the chance to see what they’d look like with different features. A particularly ambitious app will let you tour a whole house using AR, assuming you have an empty lot to walk around with your phone or tablet while doing it.

None of these things is Hard AR in the form engineers and science fiction visionaries were writing about years ago. Even when using HoloLens and Magic Leap headsets, there’s little sense that the hardware is bringing plausible digital content to life for viewers. The graphics aren’t photorealistic, the in-glasses viewing windows are small, and the positional tracking struggles to keep up with live movements. There’s something there — it’s just not anything regular consumers would buy. Due to their limited availability and high price tags, most people will never even try on HoloLens or Magic Leap devices as they exist today.

That’s unfortunate for only one reason: In the foreseeable future, seeing AR through a headset is going to be dramatically more immersive and compelling than seeing it on a screen. VR users know the distinction between Sony’s Astro Bot on a TV versus stereoscopic goggles feels like the difference between watching from afar and actually being inside the game’s environment. Once you see realistic AR objects overlapping reality in a pair of glasses, there’s a good chance you’ll want to keep seeing them.

Hence, the baby steps. As people become accustomed to using AR software on the screens they carry around every day, they’ll have a better chance of becoming dedicated AR hardware users whenever the devices are ready. Until that day comes, I’m going to continue hunting for a better term than “quasi-AR” to describe the augmented video apps that are becoming increasingly available, and arguably increasingly important, with every passing month.