Coming out party

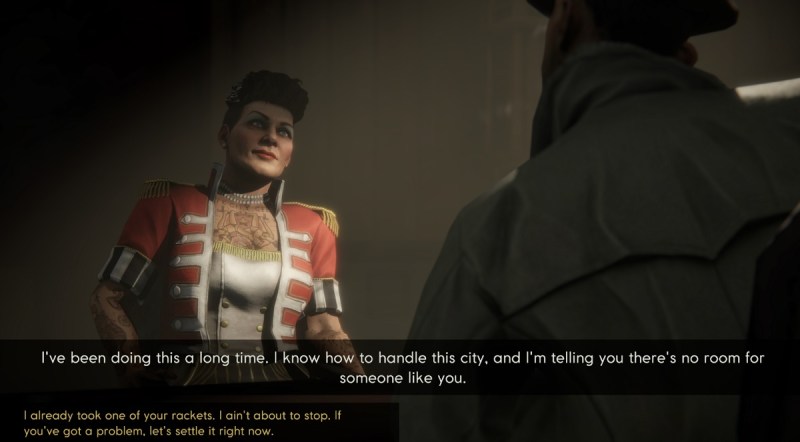

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: Did you have a good reaction to the announcement at Gamescom? Any interesting feedback that came from that?

Romero: Oh my God, yeah. This is a really direct answer, but — when you have an idea where you can’t point to something else that’s like it, it’s terrifying. It’s absolutely terrifying, because you love it. Your team, everybody, the people you’re working with, they love it. Obviously your publisher believes in it. They’ve been super supportive for us. All that’s well and good. But we’ve all seen ugly babies, right? A terrible thing to say. [Laughs]

When we announced the game at E3, the reaction was incredible. It was better than we ever would have dared hope for. And then going to Gamescom, sitting people down — we worked really hard on the build. We wanted to make sure it didn’t crash the second you looked at it. We wanted a tutorial in there so people could have a good experience. Having all that in there, the reaction, even at Gamescom, was really favorable. If you look at the review that IGN put out, and then Rock Paper Shotgun, and I’m sure there will be others to follow — generally it takes a bit for the first impressions to come out. But I’m thrilled with it.

Of course, I see all the stuff that’s yet to be done. I see the balance that doesn’t make sense in some areas. I see the screens that need to be revisited, or some of the nitty-gritty diplomacy stuff that still has to be implemented. I see all of that, and so it’s tempting, when you’re first bringing out a game, when you’re first announcing something — you still see what needs to be done, but people see what you’ve created. The response has been incredible. I wouldn’t have dared hope for anything as positive. It’s been a really warm response. It’s been great. I don’t know how you could want anything better.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Just going back to that initial point, when you’re making something somebody else hasn’t made before, well, is there a reason somebody hasn’t made this before? Is this a bad idea? Am I the only one who thinks this could be cool? We got an email from someone over the weekend, just this long email about, “This is the game I’ve waited for. Please don’t fuck this up.” We’re getting these emails like, “Thank God, we’ve been waiting for this!” But that one email with “don’t fuck this up,” please don’t let that be the trailing quote. [laughs] That would be greatly appreciated.

I don’t remember making a game that had just this much pre-fan involvement. Paradox fans are great, so it kind of doesn’t surprise me. But we’re getting people just sending emails about what they liked. Are they going to be able to do this or that? The game really seems to be resonating with people.

GamesBeat: How did you end up working with Paradox?

Romero: It’s the standard way things tend to work in the industry. Maybe some people aren’t familiar with it, but I go to Gamescom, or to a lot of these shows, and you put together a deck, maybe 20 pages describing what the core of your game is, key team members, the gameplay. You’re trying to create an idea for people. You may or may not have a prototype, but having one is certainly more helpful than not.

We went to Gamescom, and I pitched the game to — I had what I referred to as the throwaway pitch, as in, “I doubt this company would want this, but let me pitch it anyway so I can warm myself up.” I may have even had two of those, just throwaway pitches. Then it came time to talk to Paradox. I remember that meeting so vividly. I remember where I was standing, where the Paradox team was. I remember everything about that meeting.

It was one of the most tense moments, because I knew — you can’t open a pitch meeting with the following words: “This game is so for you. I know it’s for you. If there ever was a game designed for Paradox, this is the game.” You can’t open a meeting with that, because that would end the meeting. [laughs] But I believed it. I believed that they would like this game. I believed in the game. At the end of it, Shams Jorjani just said, “I love it.” I probably exhaled the biggest breath ever.

I tried to hold it together outside, because loving an idea and signing a game are two different things. But anyway, we pitched it to them at Gamescom in 2015.

GamesBeat: How long has it actually been in development, then, where you guys have been really working on it?

Romero: It didn’t get started until — it takes forever to sign a game, to actually go through all the nitty-gritty of the contracts and that sort of stuff. We started work proper at some point in 2016. Then the team grew from there.

Incorporating diversity in game design

Above: Brenda and John Romero at the Microsoft event at Gamescom 2019.

GamesBeat: You’ve been active around issues of diversity in the industry. Has some of that come back around to how you make a game like this, that’s set in a time period like this? Is there a way to do this in a more diversity-conscious way?

Romero: There are two answers I have, and they both answer the question, but I think it’s best if I split them. One, 1920s Chicago was not a fantastically nice time. The cops were super corrupt. People had brothel empires. They were selling booze illegally. It’s a seedy time that’s represented in this game. That goes with the time period.

On the diversity side, I feel super strongly that you should be able to see yourself, whoever you are, in a game. It’s not a question of me not making room for other people. I don’t want to take somebody else’s space. I just want to add a new space for somebody else. Historically, we knew that there had to be people whose shoes you could fill. Sometimes it was obvious. Sometimes it wasn’t so obvious. But just by doing a ton of research — we already had a pretty diverse cast just through research.

There’s Stephanie St. Clair, who I brought over from New York. Daniel McKee Jackson. I already mentioned Elvira Duarte. Goldie, who’s in the game because obviously you need to have a 1920s flapper there. But hopefully the starting crew of characters itself feels pretty diverse. It’s not just for diversity’s sake, but because these were the real players during that time. Daniel McKee Jackson was fantastic. He was an undertaker who had a casino empire.

Just because the stories that are told, the stories we might know about — we might have heard of Capone. Everybody’s heard of Capone. But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t a ton of other stories to be written and to be remembered. Sometimes people’s stories didn’t get written up, because they weren’t deemed newsworthy. But when you have a good 20 years’ worth of research going, you can pretty much get your hand on that stuff.

Then, when it came to the RPCs in the game, that’s an intentionally diverse cast. Talking about brothels, our brothels are equal opportunity brothels. Hopefully there’s not something pre-coded into the game that implies one envelope or another. The characters in the game don’t necessarily have gender. You can assign a gender and figure out what it is based on the way they talk and what they say. But there are certainly characters in the game that — it’s the 1920s, but I’m guessing they would identify as gender non-binary. Nowhere in the character sheet does it say that Al Capone is male.

Each of the characters is designed. They’re not random characters. They have backstories. They have friends. They have people they can’t stand. They come into the game with flaws. They could be an alcoholic. They could have gambling issues. They could come into the game in love. They’re designed, and then as you play through the game with them and the other characters they interact with, they start to develop more from there.

It was not the driving thing behind this game by any stretch of the imagination. But bear in mind that when I played games as a kid, I didn’t have an opportunity to play — if I was creating a character, I didn’t get to play as a female character. I always had to rescue the princess, right? I don’t want to perpetuate that. I also think about my son. He could adjust his glabella in a game, but he couldn’t have his skin color or his hairstyle. That sort of stuff–we don’t need to do that, so let’s not. This isn’t a platform I’m going out on, but it’s intentional. It’s designed. It’s in there. It’s important.

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: What was the immediately preceding project for you? I’m trying to remember which games you’ve worked on at the same time.

Romero: Oh God, in the background there’s all kinds of stuff. At any given time, when a game developer is hoping to get something picked up, there are probably five different things in the background.

One project which was not a game, but was as intensive as one, was packing up everything in California and moving to Ireland. That was probably a year and a half, just in terms of — okay, we’re going to wind down our company in California, start a new company in Ireland, move four kids over to Ireland. It was a massive project.

Getting here and finding a team of great people, which was actually not hard, thank God — three of our coders have worked together for 15 years. They’re amazing. Keith O’Conor was with Ubisoft. He’s originally from Ireland. For him, the opportunity to come home and work on games was great. He’s our CTO.

Making games in Ireland

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: What is the Irish game industry like right now?

Romero: The Irish game industry gets bigger every single year. Some of the biggest games to come out of Ireland — how do I describe this? Ireland has a couple of different levels. There are super healthy indies here, primarily centered in Galway and Dublin. There’s a healthy, well-connected indie scene. EA has a massive office in Galway. Riot has an office here. Blizzard has an office in Cork. Then there are the super middleware companies, like Demonware and Havok. Those are Irish born and bred. Brendan Greene, from PUBG, he’s originally from County Kildare. I know he’s not here, but there’s a lot of great stuff that’s come out of Ireland. To me, that’s laudable.

You always have to think of yourself — well, you don’t have to, and I didn’t when I came from the states. It wasn’t a question of, “What does this state offer me that that state doesn’t? Why would we set up our company here versus there?” But in Europe there can be pretty large differences between the supports that different governments provide. Right now Ireland has a very healthy film industry and a very healthy big tech industry. It’s worked out incredibly well. Most of the big tech companies have headquarters here, their European headquarters. Certainly not just for tax benefits, either.

I imagine that same attitude will start to work itself down further into the creative industries, into the creative tech industries. Games everywhere sit in this uncomfortable funding space. Tech can say, “No, that’s art,” and art can say, “No, that’s tech.” Many countries have had to go through this before, where they’ll figure out how they’ll grow their game industry. It’s not necessarily a country, but we saw this in Montreal. Montreal made a serious place for games, and you can see that turned out well. France did something similar.

It’s a very long answer, but the industry here is healthy. There have been some great success stories. It’s growing. I’m super happy we’re here. My only regret is I wish I’d moved here five years before we did. I absolutely love it in Ireland.

GamesBeat: Except for the state of Louisiana, I don’t think there’s anything the U.S. is doing to try to compete in that way.

Romero: Even the question — the reason you move to California to set up your game company is because you’re getting some big tax kickback. It’s because that’s where the coders and artists and designers and audio engineers are. But it’s so expensive. Increasingly people are leaving.

For us, we realized we could do this from anywhere. We loved it here. There’s a reason that Ireland gets as many visitors as Hawaii does. It’s nearly embarrassingly beautiful. The people are great. It’s a great way of life.

GamesBeat: Does Ireland have its own game conferences yet, or are you generally going to other countries for that?

Romero: There are some here and there. The developer conferences, not so much. There’s enough in England. There’s IMIRT, which is a game developer association here in Ireland. They have lots of things going. Sometimes there are smaller events in Galway or Dublin or elsewhere around the country. There are events here or there, but nothing in the way of big conferences yet.