With Brenda Romero‘s Empire of Sin game about the Chicago mob, the place came first. From the days when she was a curious child and her mother wouldn’t tell her about it, Romero devoured all the information you could about Al Capone’s empire in the 1920s.

Then she put it on the shelf. She made 47 other games over the course of nearly 40 years, including Jagged Alliance and Gunman Taco Truck (conceived by her son). She won many awards for her work, and she became a program director for game design and development at the University of Limerick in Ireland. She also makes games with her husband, John Romero, and her family at Romero Games.

But she finally came back to the idea for Empire of Sin, and Paradox Interactive plans to publish the game in 2020.

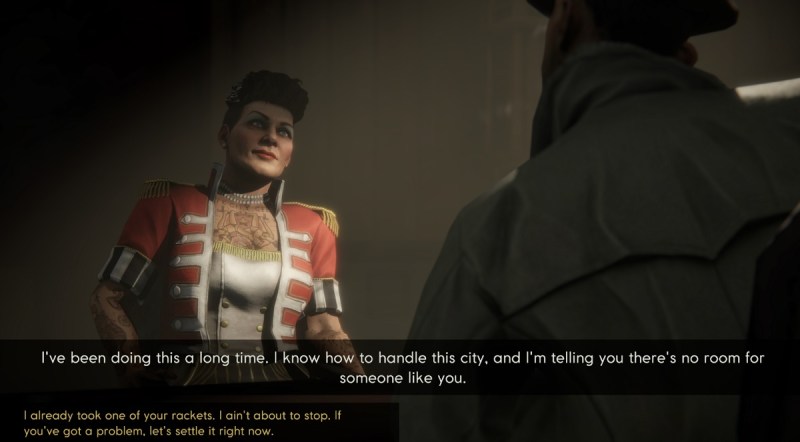

In the game, you assume the role of a young mob boss in Prohibition-era Chicago. You have to build an empire in a strategy game that includes both economic planning as well as violent attacks on rival gangs. Your empire will depend on the characters you groom for it, and you have to take their relationships into account, like whether two characters have an ongoing feud.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

For Romero, this game goes back to her childhood. She grew up in Ogdensburg, New York. Her grandfather used to walk across the river crossing to the Canadian border. There was one bar, dubbed the Place. It was the oldest continuously operating bar in the U.S., and it didn’t shut during Prohibition. Young Brenda asked her mother why, and she wouldn’t say.

So began the curiosity and the road to Empire of Sin. I spoke with Brenda Romero recently, and here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Brenda Romero

GamesBeat: I was surprised as anyone at the subject for your next game. It sounded like you had pitched this many years before, or some version of it. Has this been cooking for a long time?

Brenda Romero: The first time I pitched it was to Paradox. But Prohibition itself is a pretty broad theme. It’s an area I’ve been interested in. I spent the first 20 years of my career working primarily in RPGs, so it didn’t necessarily fit there. I guess it was a sort of side intellectual curiosity. If there was a new book about it, I’d read it. When a TV series came out, like Boardwalk Empire, I was all over that. Any movies that had to do with it.

I was trying to figure out a way to make a game that hadn’t been made. It’s an interesting theme, but I didn’t want to make something that was like a game somebody else made. Somewhere, floating in the Atlantic, probably in 2014, I thought of the game that eventually would become Empire of Sin.

GamesBeat: It all goes back to the question you asked your mother about the speakeasy?

Romero: Yeah! She was uncomfortable providing that answer. Just a bit of context, my mother — I remember once, the phone was ringing. I said, “Mom, just tell them I’m not here.” She said, “Then I won’t answer the phone.” She was not going to lie. Which is a great credit to her. For, me being a curious kid, she normally, in any other circumstance — she volunteered at the library. She would have taken me to the library with any questions I had.

With this one, she was not comfortable telling me what the truth was. Being a curious kid, to me it was like, “Oh, there must be something in there. Now I need to know about it even more.” I’m positive that her intent wasn’t to spark this massive curiosity about whatever secrets were in this place that nobody could know about, that the cops covered up. I had all kinds of ideas in my head about what it could be. But that simple refusal — you can’t know what’s behind that door — suddenly sparked all kinds of thoughts.

GamesBeat: Have you thought about that since becoming a mother yourself? Do I want to tell my kids everything about how to run a criminal empire?

Romero: [Laughs] You know, I don’t know — the interesting part about this is that I didn’t know that it was a criminal empire. You’re right. If your kids ask a question, telling them everything they need to know about crime probably isn’t the best answer. But who knows? I’m sure there’s lots of other stuff that she may not have answered. But it was the way that she pushed me off that and just wouldn’t answer, didn’t take me to the library, no books, no nothing — it made me think there was some juicy stuff there. And I was right.

Above: Empire of Sin is a strategy game.

GamesBeat: How did you spend time learning about this? Was it just books and other media, rather than any existing video games?

Romero: No, not through existing video games, although certainly — I’ve noticed there have been some games made around the time period. But my interest in it goes back to the Apple II days. I obviously wasn’t pitching it on the Apple II, but it was something I was interested in. This was a lived experience. The bar that I’ve referenced, that I talked about Gamescom, that’s a real bar. It’s still there. The stories of people who brought alcohol across the St. Lawrence River, that’s real lived experience. People’s parents and grandparents, my grandparents, they did this. There are ways to learn that are beyond games and beyond books. A huge part of it, though, was just reading.

In other games you can see — people have drawn comparisons to XCOM, which is one of my favorite games, and to Civilization, another one of my favorites. Jagged Alliance had RPCs (role-playing characters), and I always loved that. Certainly there are elements of some of my favorite games in this game, a mashup that delivers the experience I want to have.

GamesBeat: Doing it as a turn-based strategy game, how did that idea develop?

Romero: The idea to have these different empires, different criminal empires facing off against one another — the theme itself is strategic. That’s already there. If you watch Boardwalk Empire, it’s pretty clear that there’s all kinds of strategy going on. The movement of resources, how those resources are going to be protected, how they’re going to be sold — it was a real-life strategy game.

The decision between turn-based and real time, that came down to the type of gameplay I favored as a design. For me that was turn-based gameplay.

GamesBeat: Did you think about trying to do this as a particular kind of mafia game, like the Sopranos in the modern day, or did you have specific reasons to do it in the Prohibition era?

Romero: I didn’t think about doing it more modern-day. From the very beginning, I wanted to make a game — the place came first in this case. It wasn’t that I wanted to make a strategy game. I wanted to make a game about Prohibition-era Chicago, because I loved it. It was such a rich place. I love Chicago as a city. I like the potential depth of Chicago in that it has easy access to the Great Lakes, easy access to Canada. The Great Lakes provide access to the ocean. It’s become a modern-day pipeline for criminal empires to the north.

There was something about Chicago and the history of Chicago in that time that had the most depth, to me. I love Capone. I love the showdown with Elliott Ness. Some of the other mobsters of the era, I moved them over to Chicago in my alternate reality.

Mob economics

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: The economics of running an empire, is that part of the fascination here? How did they figure out how to run these underground businesses? It’s almost a kind of business simulation idea.

Romero: Yeah, it is. It goes — I say this because of where we are currently in development in the game. I’m spending a lot of my time balancing and making sure that the experience doesn’t kill you right out of the door, or we’re not leaving you feeling like, “Jeez, I’d better get moving.” But the depth of what those mobsters had to do economically is not lost on me.

First of all, there are only two resources, or three I guess. There’s money and alcohol and time. You would think that with just three resources, how much depth could you have? But my God. There’s all kinds of things that go on. If I have a brewery, how big is my brewery? If it’s really good, it might come to somebody’s attention. If I’m drawing attention I’d better make sure I have lots of security in there. I’d better try to put up a front, so people aren’t looking at it. What kind of alcohol will I brew? There are many different questions, each of which affects something else.

Strategically, just from a balance perspective — having worked on some complicated RPGs, this game, to me, is even more of a challenge to balance than that. There are so many moving parts around a relatively small core. But a lot of people are trying to get at that specific thing. You can even think about the relationships people have with one another. Are you allies? Do you have a trade pact? Do you have a non-aggression treaty? All kinds of things come into play just in terms of how you deal with the other mobsters in the game.

GamesBeat: It does inspire comparisons to XCOM, but you’re only really controlling your character, right? You’re not controlling your other companions around you.

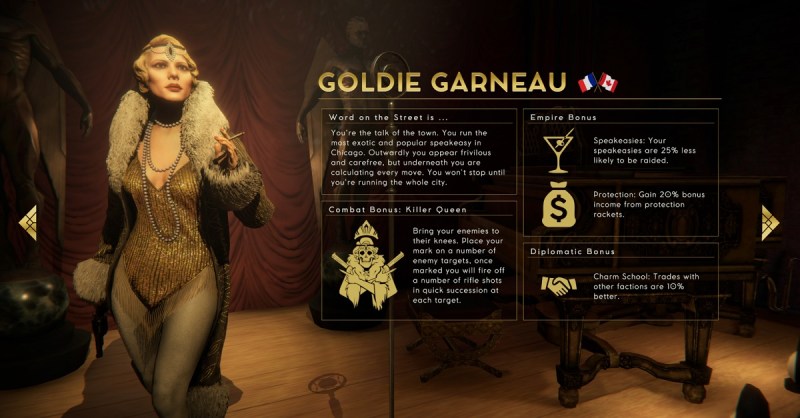

Romero: You are, actually. When you first start the game, you choose which boss you want to play. Bosses are unique visually, but they’re also unique from a strategic point of view. Each one of them has two empire bonuses, and then they have a diplomatic bonus. Capone gets on well with the other Italian gangs. Another thing about Chicago, it has this sort of — ”war” isn’t the right term, but there’s an uneasy tension between the Italians and the Irish in the city. So you have diplomatic benefits, and then each boss also has a unique combat ability. That’s your starting state.

Then you go into the game, and there are 60 different RPCs you can hire. You control those RPCs to a certain extent. They have their own agency, within reason. Just like if you were a traditional mob boss, you can tell them what to do. You control them in combat and you control their movements in the world. But it’s possible that two of your characters could fall in love with each other. As the boss, you can say, “Look, forget about this. It’s not happening.” They’ll listen to you. They might be sullen for a while. But you control those characters. They work, as you might expect, on a take. They keep some of what they make and send the lion’s share up to you.

A complicated strategy game

Above: Brenda Romero and John Romero are working on Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: These dependencies sound like they’re the thing that makes this complex technically.

Romero: There are certainly a lot of moving parts in the game. There’s loads to do. As you well know, nothing makes itself. This game would be nothing more than just an idea without the coders and the artists that are creating it.

Specifically, it’s Ian Dunbar who’s working on the RPC dynamics. He’s the person — we joke with him, because he’ll say out loud, “If two people fall in love and they something something something” — it was one of my more amusing experiences, listening to a programmer talking about how to programmatically create love and intimacy between two people.

GamesBeat: It seems like a big game for an indie team to pull off, too. Is this more ambitious than your other games? Do you have more resources at hand?

Romero: An overactive imagination, if that counts? We have, I would say, two things that we’re fortunate to have. One is that it’s a very experienced team. That pays off in so many ways. Just from how will we architect the code to lot of the design decisions that we make. That’s not to say there aren’t changes. There are obviously changes.

Then we also have a tremendous asset — I know it’s sometimes said as lip service, but in this case it’s pretty obvious, and I’ve been transparent about it. We have an ace in the hole with Paradox. If there’s a publisher that knows its players inside out, knows what they want, it’s Paradox. There are some times as a designer where I’ll think, “There are three different ways I can do this,” and we can ask Paradox, “What would your players prefer?” They’ve also been fantastic about doing lots of UR tests. Seeing how people respond to the game and making changes in the game while the clay is still soft and we can still make those changes.

You’re absolutely right that it’s an incredibly challenging and ambitious project. It wakes me up regularly at five in the morning. “Hey, have you thought of this thing? This is something that needs to be done.” It’s by far my most ambitious game. There’s not even a question about that. But so far, so good.

GamesBeat: Were there some things you learned from Wizardry or other earlier games?

Romero: Tons, believe it or not. I know the length of time it will take me to balance something based on previous times that I’ve balanced games. Wizardry, at this point in time, it’s older. It’s not the same style of game. But I did like — in Wizardry I had characters that you could recruit for your team. I loved having the interesting interactions with those characters. That certainly hasn’t been lost.

Many of the games I’ve worked on, the game doesn’t always take itself super seriously. There are things that are sometimes funny. Even though this is a very serious time and theme, there’s ridiculous stuff that happens. Capone kidnapping someone to play his birthday party. Normal people might just book a musician, but not Capone. He kidnaps Fats Waller to provide the entertainment. Stuff like that is in the game as well.

In the early Wizardry games, especially Wizardry VI I think, there was a ridiculous amount of research, enough that you could even think it was unnecessary. All of those weapons were individually researched. Why? Who knows. They could have been done in a spreadsheet. But there was that craft to it. That’s carried forward. Ian O’Neill is the guy who deserves credit for this, for the weapons research and which weapons to put in the game and what weapons might have been used in the 1920s and how they were used.

A family matter

Above: Empire of Sin

That’s something that’s carried forward, or I should say something that’s similar between the two games. I didn’t bring up Wizardry VI and say we should do it just like that. Empire of Sin is absolutely its own thing. When you brain figures out how to make something work in a way that’s not been done before, those are the moments that you live for in your career.

If you get a chance to even have one of those moments — for me, when I’m working on pitches or trying to think of something unique today, I’ll isolate myself, completely isolate myself. Usually my brain won’t stop thinking about a topic. This is a case in point. It’s some niggling thing that I keep thinking about and reading books about. I’m fearful that it’s going to come out in another giant game. But we’ll see. This one should have legs under it for a while.

GamesBeat: This genre seems as popular as ever, gangsters and the mafia in general. People are still fascinated with it.

Romero: There’s certainly a lot to the theme. You could put any genre next to this. You could have a Prohibition-era adventure game, a shooter, an RPG. Platformer might be pretty weird? [Laughs] But you could do it. There’s lots of stuff.

For me, once I figure out the theme, then I’m trying to hone in on what might be the most interesting — even though Paradox had picked up the game and we knew we were making it with them, even in the very earliest days, a lot of the game was formed with me and the coders at the time sitting around a table and saying, “If you could do anything, what would you want to do?” Playing it like a role-playing game. Many of the actions you can take in the game now come out of those early sessions. Obviously I thought through some of those things for the pitch as well.

That’s my very long way of saying that I like to make games that I could also play off the computer. To me that’s a richer experience. It’s also an easier way to prototype.

GamesBeat: How much of the family is helping with this?

Romero: [Laughs] I guess we’re in a fortunate situation. We have a literal family business. John is obviously working on design and production stuff. The other kids, as they can, are testing the game. But I should say, there’s an actual fully functional testing department. They’re more like, “Hey, can we have access to the build?” I think it’s safe to say that for this one it’s just John.

GamesBeat: The kids are learning something about criminal empires, then.

Romero: [Laughs] Unbelievably, yeah. But you know what, it occurs to me — John’s great-grandmother is in the game. She’s Elvira Duarte, who actually ran a brothel empire in Mexico, in Nogales. There’s been some funny comments on my Facebook wall, where one of John’s cousins will say, “Oh, mama Elvira is going to be in the game! That’s going to be pretty wild!” I guess she counts as another one.

John has a really colorful family. My family — Frankie Donovan, my great-grandfather, he lived in Canada at the time. He was an Irish immigrant to Canada. He would have brought alcohol across the St. Lawrence, which wasn’t deep at the time. It hadn’t been dredged, so it would easily freeze over in the winter. His real name was Paddy Donovan, but because nobody would possibly believe that, and it could have been interpreted as sort of mocking, we went with Frankie. But there’s nothing about Frankie that didn’t look Irish.

Coming out party

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: Did you have a good reaction to the announcement at Gamescom? Any interesting feedback that came from that?

Romero: Oh my God, yeah. This is a really direct answer, but — when you have an idea where you can’t point to something else that’s like it, it’s terrifying. It’s absolutely terrifying, because you love it. Your team, everybody, the people you’re working with, they love it. Obviously your publisher believes in it. They’ve been super supportive for us. All that’s well and good. But we’ve all seen ugly babies, right? A terrible thing to say. [Laughs]

When we announced the game at E3, the reaction was incredible. It was better than we ever would have dared hope for. And then going to Gamescom, sitting people down — we worked really hard on the build. We wanted to make sure it didn’t crash the second you looked at it. We wanted a tutorial in there so people could have a good experience. Having all that in there, the reaction, even at Gamescom, was really favorable. If you look at the review that IGN put out, and then Rock Paper Shotgun, and I’m sure there will be others to follow — generally it takes a bit for the first impressions to come out. But I’m thrilled with it.

Of course, I see all the stuff that’s yet to be done. I see the balance that doesn’t make sense in some areas. I see the screens that need to be revisited, or some of the nitty-gritty diplomacy stuff that still has to be implemented. I see all of that, and so it’s tempting, when you’re first bringing out a game, when you’re first announcing something — you still see what needs to be done, but people see what you’ve created. The response has been incredible. I wouldn’t have dared hope for anything as positive. It’s been a really warm response. It’s been great. I don’t know how you could want anything better.

Just going back to that initial point, when you’re making something somebody else hasn’t made before, well, is there a reason somebody hasn’t made this before? Is this a bad idea? Am I the only one who thinks this could be cool? We got an email from someone over the weekend, just this long email about, “This is the game I’ve waited for. Please don’t fuck this up.” We’re getting these emails like, “Thank God, we’ve been waiting for this!” But that one email with “don’t fuck this up,” please don’t let that be the trailing quote. [laughs] That would be greatly appreciated.

I don’t remember making a game that had just this much pre-fan involvement. Paradox fans are great, so it kind of doesn’t surprise me. But we’re getting people just sending emails about what they liked. Are they going to be able to do this or that? The game really seems to be resonating with people.

GamesBeat: How did you end up working with Paradox?

Romero: It’s the standard way things tend to work in the industry. Maybe some people aren’t familiar with it, but I go to Gamescom, or to a lot of these shows, and you put together a deck, maybe 20 pages describing what the core of your game is, key team members, the gameplay. You’re trying to create an idea for people. You may or may not have a prototype, but having one is certainly more helpful than not.

We went to Gamescom, and I pitched the game to — I had what I referred to as the throwaway pitch, as in, “I doubt this company would want this, but let me pitch it anyway so I can warm myself up.” I may have even had two of those, just throwaway pitches. Then it came time to talk to Paradox. I remember that meeting so vividly. I remember where I was standing, where the Paradox team was. I remember everything about that meeting.

It was one of the most tense moments, because I knew — you can’t open a pitch meeting with the following words: “This game is so for you. I know it’s for you. If there ever was a game designed for Paradox, this is the game.” You can’t open a meeting with that, because that would end the meeting. [laughs] But I believed it. I believed that they would like this game. I believed in the game. At the end of it, Shams Jorjani just said, “I love it.” I probably exhaled the biggest breath ever.

I tried to hold it together outside, because loving an idea and signing a game are two different things. But anyway, we pitched it to them at Gamescom in 2015.

GamesBeat: How long has it actually been in development, then, where you guys have been really working on it?

Romero: It didn’t get started until — it takes forever to sign a game, to actually go through all the nitty-gritty of the contracts and that sort of stuff. We started work proper at some point in 2016. Then the team grew from there.

Incorporating diversity in game design

Above: Brenda and John Romero at the Microsoft event at Gamescom 2019.

GamesBeat: You’ve been active around issues of diversity in the industry. Has some of that come back around to how you make a game like this, that’s set in a time period like this? Is there a way to do this in a more diversity-conscious way?

Romero: There are two answers I have, and they both answer the question, but I think it’s best if I split them. One, 1920s Chicago was not a fantastically nice time. The cops were super corrupt. People had brothel empires. They were selling booze illegally. It’s a seedy time that’s represented in this game. That goes with the time period.

On the diversity side, I feel super strongly that you should be able to see yourself, whoever you are, in a game. It’s not a question of me not making room for other people. I don’t want to take somebody else’s space. I just want to add a new space for somebody else. Historically, we knew that there had to be people whose shoes you could fill. Sometimes it was obvious. Sometimes it wasn’t so obvious. But just by doing a ton of research — we already had a pretty diverse cast just through research.

There’s Stephanie St. Clair, who I brought over from New York. Daniel McKee Jackson. I already mentioned Elvira Duarte. Goldie, who’s in the game because obviously you need to have a 1920s flapper there. But hopefully the starting crew of characters itself feels pretty diverse. It’s not just for diversity’s sake, but because these were the real players during that time. Daniel McKee Jackson was fantastic. He was an undertaker who had a casino empire.

Just because the stories that are told, the stories we might know about — we might have heard of Capone. Everybody’s heard of Capone. But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t a ton of other stories to be written and to be remembered. Sometimes people’s stories didn’t get written up, because they weren’t deemed newsworthy. But when you have a good 20 years’ worth of research going, you can pretty much get your hand on that stuff.

Then, when it came to the RPCs in the game, that’s an intentionally diverse cast. Talking about brothels, our brothels are equal opportunity brothels. Hopefully there’s not something pre-coded into the game that implies one envelope or another. The characters in the game don’t necessarily have gender. You can assign a gender and figure out what it is based on the way they talk and what they say. But there are certainly characters in the game that — it’s the 1920s, but I’m guessing they would identify as gender non-binary. Nowhere in the character sheet does it say that Al Capone is male.

Each of the characters is designed. They’re not random characters. They have backstories. They have friends. They have people they can’t stand. They come into the game with flaws. They could be an alcoholic. They could have gambling issues. They could come into the game in love. They’re designed, and then as you play through the game with them and the other characters they interact with, they start to develop more from there.

It was not the driving thing behind this game by any stretch of the imagination. But bear in mind that when I played games as a kid, I didn’t have an opportunity to play — if I was creating a character, I didn’t get to play as a female character. I always had to rescue the princess, right? I don’t want to perpetuate that. I also think about my son. He could adjust his glabella in a game, but he couldn’t have his skin color or his hairstyle. That sort of stuff–we don’t need to do that, so let’s not. This isn’t a platform I’m going out on, but it’s intentional. It’s designed. It’s in there. It’s important.

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: What was the immediately preceding project for you? I’m trying to remember which games you’ve worked on at the same time.

Romero: Oh God, in the background there’s all kinds of stuff. At any given time, when a game developer is hoping to get something picked up, there are probably five different things in the background.

One project which was not a game, but was as intensive as one, was packing up everything in California and moving to Ireland. That was probably a year and a half, just in terms of — okay, we’re going to wind down our company in California, start a new company in Ireland, move four kids over to Ireland. It was a massive project.

Getting here and finding a team of great people, which was actually not hard, thank God — three of our coders have worked together for 15 years. They’re amazing. Keith O’Conor was with Ubisoft. He’s originally from Ireland. For him, the opportunity to come home and work on games was great. He’s our CTO.

Making games in Ireland

Above: Empire of Sin

GamesBeat: What is the Irish game industry like right now?

Romero: The Irish game industry gets bigger every single year. Some of the biggest games to come out of Ireland — how do I describe this? Ireland has a couple of different levels. There are super healthy indies here, primarily centered in Galway and Dublin. There’s a healthy, well-connected indie scene. EA has a massive office in Galway. Riot has an office here. Blizzard has an office in Cork. Then there are the super middleware companies, like Demonware and Havok. Those are Irish born and bred. Brendan Greene, from PUBG, he’s originally from County Kildare. I know he’s not here, but there’s a lot of great stuff that’s come out of Ireland. To me, that’s laudable.

You always have to think of yourself — well, you don’t have to, and I didn’t when I came from the states. It wasn’t a question of, “What does this state offer me that that state doesn’t? Why would we set up our company here versus there?” But in Europe there can be pretty large differences between the supports that different governments provide. Right now Ireland has a very healthy film industry and a very healthy big tech industry. It’s worked out incredibly well. Most of the big tech companies have headquarters here, their European headquarters. Certainly not just for tax benefits, either.

I imagine that same attitude will start to work itself down further into the creative industries, into the creative tech industries. Games everywhere sit in this uncomfortable funding space. Tech can say, “No, that’s art,” and art can say, “No, that’s tech.” Many countries have had to go through this before, where they’ll figure out how they’ll grow their game industry. It’s not necessarily a country, but we saw this in Montreal. Montreal made a serious place for games, and you can see that turned out well. France did something similar.

It’s a very long answer, but the industry here is healthy. There have been some great success stories. It’s growing. I’m super happy we’re here. My only regret is I wish I’d moved here five years before we did. I absolutely love it in Ireland.

GamesBeat: Except for the state of Louisiana, I don’t think there’s anything the U.S. is doing to try to compete in that way.

Romero: Even the question — the reason you move to California to set up your game company is because you’re getting some big tax kickback. It’s because that’s where the coders and artists and designers and audio engineers are. But it’s so expensive. Increasingly people are leaving.

For us, we realized we could do this from anywhere. We loved it here. There’s a reason that Ireland gets as many visitors as Hawaii does. It’s nearly embarrassingly beautiful. The people are great. It’s a great way of life.

GamesBeat: Does Ireland have its own game conferences yet, or are you generally going to other countries for that?

Romero: There are some here and there. The developer conferences, not so much. There’s enough in England. There’s IMIRT, which is a game developer association here in Ireland. They have lots of things going. Sometimes there are smaller events in Galway or Dublin or elsewhere around the country. There are events here or there, but nothing in the way of big conferences yet.