Monetizing esports is still a work in progress. The idea of watching people get paid to play games seemed far-fetched not long ago. But market researcher Newzoo estimates that 165 million esports enthusiasts are now watching esports, with that number expected to reach 250 million by 2021. Occasional viewers will drive those numbers to 557 million by 2021.

That means that esports has a huge chance to surpass both the revenues and the viewership for traditional sports — if only the teams, leagues, broadcasters, streaming companies, and video game publishers can figure out the best business models for monetization.

We talked about this challenge in a recent webinar on esports monetization. Our expert panelists included Jonathan Singer, industry strategist at Akamai; Robb Chiarini, director of esports at Ubisoft; and Kent Wakeford, chief operating officer at Gen.G, an esports organization.

Esports has many different avenues for driving revenue. Those include advertising, sponsorship, merchandising, ticket sales, concessions at events, media rights, streaming videos, and prize money. There are many ways to innovate across all of those categories.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

The session was moderated by VentureBeat’s Rachael Brownell and me. It was sponsored by Akamai. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Above: Kent Wakeford of Gen.G speaks at GamesBeat Summit in April, 2018.

Dean Takahashi: We have a great panel here today to talk about esports and monetization. I’ll ask our panels to introduce themselves a bit first. Let’s start with Jonathan, from Akamai.

Jonathan Singer: I’m our gaming industry strategist, which means I get to talk about video games all day, which is pretty cool. At Akamai we secure and deliver fantastic digital experiences for the world’s top brands. We were instrumental in helping the video game industry move from physical to digital distribution as the primary model of game distribution. That’s the quick rundown on Akamai and myself.

Robb Chiarini: I’m director of esports at Ubisoft. I’ve been there for five years now. I’ve had a great career in video games with Blizzard before that, IGN before that. I’m a community guy that’s done this for a very long time, long before we had the term “esports.” I’m an evangelist about esports. Anything I can do to help the ecosystem. I’m super excited to talk about this today.

Kent Wakeford: I’m co-founder of Gen.G Esports. Gen.G is a global esports company that owns and operates seven esports teams, including the Seoul Dynasty in the Overwatch League. We have the 2017 world championship League of Legends team, a two-time world championship Heroes of the Storm team, a championship PUBG team, our Clash Royale team in China, which plays in Shanghai, as well as our newly announced Fortnite team, which trains and plays in the U.S.

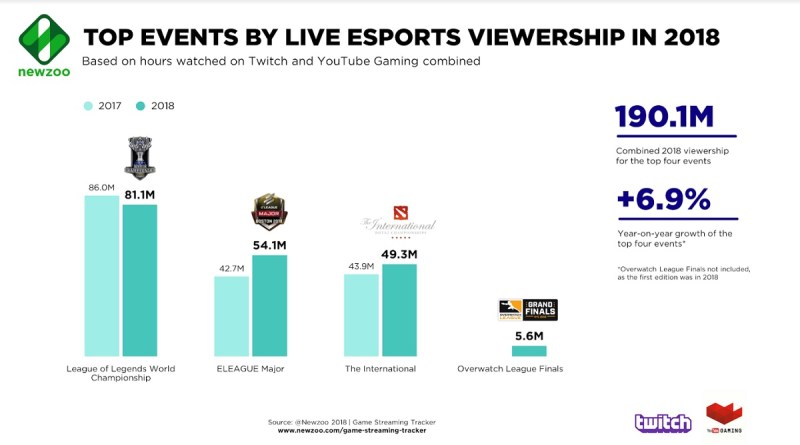

Above: Newzoo sees live esports viewership growing for some big events.

Takahashi: Everybody’s here because we all know esports is a big deal. Compare that to where it was just two, three years ago. Newzoo, the market researcher, anticipates that esports is going to be a $1.7 billion industry by 2021. The excitement around deals is all over the place. I happen to be writing esports stories every week, if not a few times a week these days.

Since we’re VentureBeat, we’ll go straight to the money talk here. Kent, what are the current esports revenue models, and where is the bulk of the revenue coming from today?

Wakeford: If you think about esports at the league and the team level, the easy analogy is with traditional sports. Let me start with an analogy to the 2018 World Series, Boston Red Sox and LA Dodgers, and the 2018 League of Legends world championship, with China’s Invictus and Europe’s Fnatic.

If we think about revenue coming out of these games, we can start with media rights as the first pillar, which we know is the big revenue driver for traditional sports. In the World Series we had Fox as the broadcaster. The World Series had about 14.3 million average viewers for the games. Compare that to League of Legends. Their broadcast rights are more on digital streaming platforms like Twitch, with worldwide viewership of 78.5 million. Media rights is a key and dominant revenue driver, both in traditional sports as we’ve seen, and now quickly gaining in esports, because of the massive viewership.

That’s number one. Number two, you see live events. Going back to the analogy of the World Series versus the League of Legends world championships, live events, sold-out stadiums—for League of Legends it was in Korea. For the World Series it was New York and Boston. But you have tens of thousands of people buying live tickets, concessions, and everything else.

Then you get to sponsorship. Sponsorship is a big, big area of growth for esports. You’re seeing, at the league level, great brands coming into esports like Toyota and T-Mobile and others. On the team level you’re seeing big brands, both endemic brands and non-endemic brands, coming in and sponsoring teams and players.

So you have media rights, sponsorship, and live events. Merchandise is another big area. You’re starting to see that grow. There are some great esports teams doing a great job, whether that’s 100 Thieves or Fnatic. And then the last area – and this is revenue that ultimately flows down mainly to the players – is prize winnings. Whether it’s the player pool for the World Series that goes to the players, or the prize pools for League of Legends or DOTA or any other games, that money flows to the teams, and the majority ultimately goes to the players.

From a revenue perspective, media, sponsorship, live events, merchandise, and prize winnings are the pillars. The biggest revenue driver to the leagues, currently, is media rights. What we’re seeing today is that the largest revenue driver for the teams is sponsorship revenue.

Above: Rob Chiarini, director of esports at Ubisoft.

Takahashi: Robb, I guess we shouldn’t forget that sales of games going directly to game publishers is a big part of this too.

Chiarini: Yeah, exactly that. When we look at esports in the current revenue models, as he mentioned, we look at a lot at traditional sports. I’d always say to look at traditional entertainment, too. Look at TV shows. At the end of the day, esports itself is a viewership phenomenon. There are players and all these mechanics within it, but it’s no different from actors and players in other sports. We all agree that the viewership is what’s super impressive. From viewership you get merchandise, people viewing and traveling and spending. That’s where you get the buying power for sponsors and others.

On top of that, for us, when we compare ourselves to traditional sports—traditional sports had to go this rate. If you’ve ever heard me talk about these things, I talk about how traditional sports have to sell media rights. They have to have sponsors. They have to have advertisers. They have to have all this influx of money, because they don’t have anything, at the end of the day. They don’t own the ball. You and I could start up a new football league tomorrow if we wanted to and no one can stop us from using that sport as a vehicle for a program. We’d get our own sponsors, do our own things, and we could do anything we wanted. Nobody owns the IP of the football.

With video games, we’re in a very different place, in that we can look at things differently if we choose to. As many esports start up, they look at it going, hey, this is a marketing a vehicle, a messaging vehicle, an engagement vehicle, a community retention and engagement vehicle, rather than a P&L against a thing to provide an entertainment that creates profit. For us, owning the game gives us the opportunity that every activity we do, every dollar we spend on an esport, is actually a way for us to engage with our existing communities, create viewership, create playership, create opportunities for monetization within the game and on the game itself.

All of that is super interesting. I believe esports has the biggest leg up against traditional sports in that way. Adding to that—I agree with your list, merch and media rights and things. There are some other things that are interesting. Gambling is out there in the space, not that I’m a proponent or otherwise, but that’s a revenue stream that’s out there in the world. Fantasy leagues, gambling sites, things like that. Another thing we do in esports, or in gaming in general, is interactive money. When you look at things like Twitch Bits and things of that nature that allow people to purchase around the game, that’s different from the traditional sports. That’s another revenue opportunity within the ecosystem, and for all of gaming.

Takahashi: A lot of influencers out there are making a lot of money from esports-related live streams and other things.

Chiarini: I go back to the drops and items and things inside the game, different layers of monetization. We’d categorize that underneath gaming. But there’s the whole other platform life. Twitch Bits is a good example, an external currency that’s involved in the ecosystem. Somebody is spending to do things with that.

Subscriptions are subscriptions. Move that to one side. It doesn’t matter if you subscribe to Netflix, which is a very strong competitor to esports. Anything that takes eyeballs away from something else is a competitor. Not everyone looks at it that way, but I think gaming companies, esports companies, everyone of us is an entertainment medium and we should look at all of those spaces as potential threats. Subscription models are just another source of revenue.

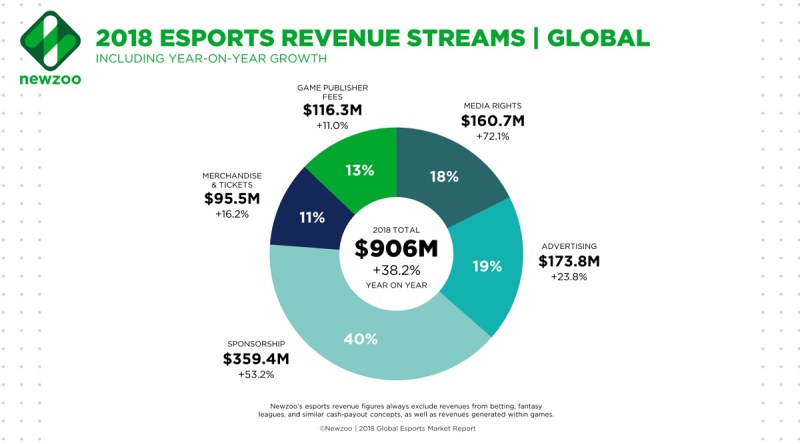

Above: Sponsorship is the biggest source of revenue for esports in 2018.

Jonathan Singer: I have a little bit of a bomb to throw, which I feel is a good way to start off a panel. [laughs] That is, we talk about where the revenue is growing to. I think it’s supposed to be $904 million this year and then a billion soon enough, with 380 million global viewers. That’s a nice size of audience. But when you do the division there, you’re talking about $2.60 a user.

If you look at the companies that are coming in, you have all the big names in video games. You have big names from outside. Again, this is VentureBeat, so people are worried about the money. Is that enough money to go around? It’s not a lot of money yet. I know we’re growing as an industry, but when we’re talking about revenue models, you have to talk about how we’re getting there and how we get—everyone’s fighting for a slice of that pie.

Wakeford: I think what you just framed up is one of the most exciting opportunities in esports. Goldman Sachs had a report recently where they showed that the average esports consumer monetized to about $3.94. Whereas the average consumer in traditional sports is monetizing to about $54. That means there’s a 10X opportunity within the esports market to grow and build those connections with fans, to bring them things they’re willing to pay for, for their excitement and their fandom and their engagement with teams and players. I view that as an opportunity.

When I look at the revenue growth drivers in esports, I think they’re all way under what the reality is going to be. We see it in the viewership. We see what’s happening on a global basis with stadiums being built all around the world – in the U.S., in China, in Korea. We see brand sponsors coming in. We see bigger media rights deals happening. We see merchandise. We just saw the announcement with the Overwatch League and Fnatic doing merchandise. It’s moving at a much faster speed than a lot of the industry reports have been putting out. That’s the opportunity. That’s why you see so much capital coming into esports.

Chiarini: When we talk about esports, we’re comparing this giant macro of a term, across a huge industry, multiple titles, multiple games, multiple sports if you will. It’s a gigantic term we use to encompass everything. Different publishers, different games, different titles, these are all different points along that cycle. Some further along, some back behind. Some new, some starting, some growing. It’s not equal across the board. We’re talking from a very macro view. I think that’s important, because I know some of the people watching are new to esports and trying to understand that. It encompasses so much when we talk about esports as a class.

Takahashi: There are definitely winners and losers already at this stage in the game. Everyone saw the news that the H1Z1 league shut down in mid-season.

Chiarini: I would never say that there are necessarily losers. Again, it’s a strategy. Esports itself might not meet certain games and certain appetites for different things. They might feel that some other marketing strategy or activity that they’re doing is more beneficial and this isn’t proving out the results that they want. It’s tough. What scope works for your game at that time, and things change.

Singer: Kent’s response was pitch perfect. What I was looking to get at, when you talk about the difference between the ARPPUs for esports and for traditional sports–when you look at the demographics, if you look at baseball in the U.S., the bulk of their demographic is over 55 years old. Versus esports, it’s millennials and Gen Z. You need to think about — we’ll get to that in the next question as well — engagement, and how you’re engaging with them from a technological standpoint, because these are the digital natives everyone in advertising has been talking about for years.

How are they going to interact with esports? Where are they going to interact with esports? What do they expect from their viewing experience? That’s where you see, as we move from traditional revenue models around the base that traditional sports built to future interesting revenue models Robb alluded to with perks and in-game currency, to other ways of interacting with fans. That’s my point I want to make until we get to the next question.

Above: Female esports players are on the rise.

Takahashi: That’s a good point. The perks part of streams, tips that happen in those streams, those are things that don’t happen in the traditional sports revenue picture. That’s something interesting about how much more digital the esports infrastructure is.

Chiarini: You brought up age, the 55-year-old average age of baseball viewers. All of our esports fans are growing older too. As they mature and raise families on esports, just like previous generations did on baseball–not that I’m saying baseball is going away, but we’re starting to see legacy now like traditional sports have had. Your parents may have been sports fans, so they took you to games and you became a fan. We’re seeing that same thing happen with esports. Even for us, for all of us looking at esports now, and what that demographic is–as it’s aging and maturing, what’s the value proposition for those people, as well as new fans? It’s going to be an exciting elongated process for that.

Singer: Just to make sure, Robb, Ubisoft isn’t bringing up a public stance that they’re going to kill baseball.

Chiarini: Uh…no? I think there’s enough room for everyone, for all these games, for the different sportsballs and everything else. There’s plenty of room for everyone, an appetite for each of us.

Takahashi: We’ve gone into a bit of this already, but what lessons can be learned, both positive and negative, so far? Traditional sports lessons, but other lessons as well.

Wakeford: As a team owner, I think there’s a lot of great lessons from traditional sports. There’s a lot of areas to innovate, especially with the digital connection between fan and player. We talked about a lot of the traditional revenue streams and media. There’s a lot of room for improvement in looking at how traditional sports have been able to really engage fans in broadcast and go deep into player backgrounds and create a connection with storytelling around players. You’ll see that emerge in this coming year in esports.

Sponsorship we touched on. The gates are open and that’s happening. Another big area is live events. As I mentioned before, there are stadiums and arenas opening up all around the United States and the world for esports events. You’ll see a lot of innovation in how events are put on and engage people to come and have a great time. And then merchandise is another area that traditional sports teams have done a great job with. You’ll see that evolve.

One other area that’s also evolving, and we’ve spent a lot of time on this at Gen.G–we planted a flag in South Korea, the birthplace of esports. If you think about a lot of the players within esports, so many of them are from Korea. It’s like Brazil in soccer in terms of so many great players coming out of South Korea. What you’re seeing now is a whole infrastructure being built around the trading of players. That’s another area of revenue that you’ll start to see. Whether you look at the soccer teams or other professional teams, you’ll see trading of players become another big area of growth. As an esports team owner, I’m looking a lot at traditional sports for best practices in that area.

Chiarini: As I alluded to earlier, monetize everything. Traditional sports, they do a great job of every potential revenue source around the thing they create and how to monetize that, how to build upon that. To Kent’s point, how do we create deeper connections with fans, through storytelling and other pieces of content? How do you tell the story and own this ecosystem that you’ve created? Some of the traditional sports team and sports leagues do a great job of revealing that humanity that we all can connect to and do something with that.

Above: LA Valiant at the Overwatch League.

Takahashi: I’ve looked at the Overwatch League and the structure for that, with the emphasis on local teams. That seems a pretty good mirror of traditional sports, where almost all traditional sports out there are really tied to local teams and local audiences coming out to stadiums. They’re not coming from around the globe to fill a stadium in New York City. I thought it was interesting that Mike Sepso, the co-founder of MLG, just joined the New York Excelsior team to try to develop that local audience and local revenue opportunity there.

Other kinds of games out there, though, don’t have that localized structure at all, like Rainbow Six: Siege. Robb, I don’t know whether you guys are looking at whether localization of esports is going to be a huge opportunity.

Chiarini: That’s great timing for me, in that–Ubisoft traditionally is a very territorial and regionally strong company. We have 36 offices around the world, studios. Each of our different regions and communities have their own marketing teams on the ground, as well as community teams to support local initiatives. We split the world in half between NCSA and NEA, but then within each of those regions, we have very strong markets. It’s always been a strength of ours.

At times there’s been conflict. You have all these different programs and things going on, and trying to make it a holistic approach can be difficult and challenging. For esports it’s been a change in the way we operate our business in that we’ve always been so strong at the local level. Bringing something up to a global level with our pro league and being able to do something worldwide was a growing pain. It was challenging, but fun.

On top of doing our global pro league, where we have a North America region and Latin America and Europe, we’re also starting up, in each of those regions, localized national programs. For instance, in the U.S. we have the U.S. Nationals, which is a U.S.-based program. All the teams have to reside within the U.S. somewhere. We’re splitting it into eastern and western conferences, very traditional to sports. Our finals are coming up next weekend in Las Vegas. It’s really about the local market and adding a layer of esports at the professional level to cater to that particular market, just as you’d mentioned.

We’re doing those programs all over the world — Brazil, France, Belgium, all these other different groups are spinning up local initiatives on top of the global stuff. It’s a little bit faceless in some ways when you have an “NA” team. That can be difficult for somebody to connect to. But a U.S. team that’s based out of the west coast, that’s very familiar. You can connect with that a bit better. That’s one of the initiatives we’re tackling.

Takahashi: The audience might benefit from understanding a bit more about the Overwatch League and how that’s structured. There’s a buy-in that the owners pay to get a slot for a team, but there’s also revenue sharing coming back. Kent, can you talk about some of that?

Wakeford: What the Overwatch League has done, as well as what Riot’s done with franchising for League of Legends last year, that’s changed the overall dynamic within the esports market. In my opinion, it’s really propelled the growth of the entire market. With franchises, where you pay money to buy in and secure a lot, similar to a sports team buying into a league, and you own that.

You own it in perpetuity, which means that as a team owner, I can make a long-term investment. I can sign long-term agreements with my players. I can sign long-term sponsors. I can invest in marketing. In the Overwatch League, where we’ll be hosting live events in our own arena in Seoul, I can invest in the infrastructure to be able to host live events. That really changes the dynamic and the investment thesis going into esports. That’s what’s made me so excited. I believe that franchising is here to stay. It’s what ‘sunlocked a rapid and massive flow of capital into the esports market.

To your question about league revenue sharing, now that we’ve paid into the league and we own a franchise, own a part of this league, as the league sells sponsorships and merchandise and in-game assets, there’s a rev share back to the teams. Over time we receive value back from the league, from all the activities the league does. It’s a great model, and it’s been great for us as a team ownership group.

Takahashi: It’s like a dividend you get back when you buy a blue chip stock, something like that.

Wakeford: That’s a good analogy. [laughs]

Singer: We’re talking about lessons learned from traditional models and where we’re going, but one of the things that traditional models haven’t had to deal with–in a way they’ve sort of had to deal with this, in that sports players are personalities with their own brands. But are there any questions around cash flow and what you do with players who not only own their own brand, but own their own channels?

There’s a weird divide between esports and personal broadcasting, right? Players bring their audiences with them. They have Twitch channels or they’re on Mixer or what-have-you. As a team owner, you need to play back and forth with their need to keep their channel alive, or compensate them for losing their channel. If you want Ninja to leave his daily Fortnite channel to be on your Fortnite team, you’d have to pony up a lot of money. Is that a concern at the team level? What are both of you dealing with around this as you talk esports?

Above: Seoul Dynasty is an Overwatch League team.

Wakeford: It’s a great a question, and it’s a very real dynamic within esports. As a team owner, we view this as an opportunity. All of our players stream. They stream on Twitch. They stream on other channels throughout China and other areas of the world. It’s part of the everyday life of a player within esports. From a compensation perspective, that goes into the compensation for the player. They’ll get the bulk of the revenue being derived from their channel on Twitch, but they’re going to do it under the team brand.

For a player, the more views and subscribers and followers they have, the more money they’ll make from streaming. What you’re seeing is a lot of both the highly dedicated professional players, as well as streamers who are playing in Fortnite and other games–streaming is a fundamental part of esports. As a team ownership group what you need is to be able to balance how much time your players are spending on streaming versus training. That’s the interesting dynamic for a team ownership group. The rest of it all just flows through in the economics to the players.

Singer: The reason I wanted to start off with that is because I was curious as to how that confuses advertisers. We talked about advertising being one of the main revenue forms, both in traditional sports and in esports. In traditional sports the NBA had to figure out how to get you to keep watching your TV and not walk away when commercials came up. There are ways to do that around relevance of the content.

When we all got on this webinar, one of the first things Rachel said was, “Please disable your pop-up blockers.” One of the big concerns is around the relevance of your advertisements and the fact that in many of these big markets, ad block penetration is incredibly high. That’s between 15 to 25 percent in a lot of developed markets like the United States and western Europe and Australia. It’s even higher in Scandinavian countries, and in India as well. More than 25 percent of people are using ad blockers.

That’s a big issue that I think folks are going to have to target when they look at how they’ll extract money from esports. If you install an ad blocker, that probably means the content you’re being served isn’t relevant. “This is a bother to me,” versus–if the new Star Wars trainer is coming out, Robb, whatever he thinks of the past two movies, he’d go out and watch that trailer, because that’s relevant advertising. I know Robb loves Star Wars. There’s a big question around relevance of advertising that I think this market needs to answer going forward.

Wakeford: Let me jump in from a team perspective. I keep going back to opportunities. One of the big reasons why sponsors, big brand sponsors, are jumping into esports is to be within the stream. Not an ad that can be blocked.

We talked about the percentage of ad blockers, but really, with the audience of esports, they’re millennials, right? These are millennials who watch more esports than baseball or the NHL. Yes, they have a high propensity for ad blockers and everything else. But when they’re watching the stream and what is in the live stream, whether that’s the player’s jersey sponsors — in our case Nighthawk — or the brands that are integrated into the actual live viewing of an Overwatch game, those brands are not being blocked by ad blockers.

Those brands are part of the fabric of esports. They’re supporting the teams and the leagues. That’s the opportunity for brands that come in. They’re able to connect with this highly targeted demographic of millennials. They’re able to get in front of them and be part of the conversations. That’s one of the big reasons why I see so many big brands looking and starting to engage with esports. It’s specifically this ability to connect with a highly valuable demographic in an authentic way.

Above: The Clash Royale League world finals are headed to Japan.

Takahashi: There are a lot of inescapable ads out there, right? And that’s the goal. We did go into this a bit already, but I’m curious how some of the conversations go with brands, about how you get into esports. Are there any technologies that can accelerate brands jumping into esports?

Singer: I’ll hop on this first, being the technology provider. We’re talking about making money and how you engage your audience. Obviously the first way, when you think about esports, is large-scale live events. Those viewing experiences need to be the highest quality viewing experiences. All of these events are driving 10 times the engagement that on-demand events do. Your long tail doesn’t match that big burst of engagement and social presence and everything that goes along with it.

I’m going to try to make this answer fairly brief, rather than a big technology pitch. But at Akamai we see three keys to making the most of that opportunity in your big event. That’s the quality and reliability and scalability of your stream. I’ll give you a quick example. Earlier this year, the India Premier League for cricket — I know we’re talking esports, but bear with me — it had the world’s biggest online viewing event to date. We had 10.3 million concurrent viewers. At Akamai we hosted 65.3 terabits per second of traffic on the network.

Why is this a big deal for esports? There are two reasons. One is, these conversations–that’s where we want esports to go. We want these huge events with everyone viewing at the same time. That’s the size you want to have. The thing about the audience, again, and I alluded to it earlier–what device are they watching on? What network are they watching on? How are they engaging with your content? There are a lot of mobile viewers. People want to watch on the train. People want to watch everywhere.

The second is that, when we’re looking at this event happening in India, we actually had folks testing the network in train stations in Mumbai and Delhi to make sure that the network was functioning. It’s going to be the same for esports. Kent is going to have viewers watching on their phones on trains in Seoul. Or maybe I want to watch his match this morning at 6AM on my commuter rail trip. For these top-quality online event experiences, you need to have a really strong CDN partner that has all of those bases covered in scalability, reliability, and quality.

That’s what we’ve done. It’s what we did with the India Premier League and with a lot of the biggest large online events in the world. That’s my pitch and what we really think, as far as technology being important. It’s to make sure the infrastructure is there to have these massive online events happening, and have people engage with them in real time.

Above: A Seoul Dynasty fan cheers on his team in the Overwatch League

Wakeford: Obviously what Akamai does is critical for the overall ecosystem to exist. I think as it relates specifically to sponsors and brands, what brands are going to look for as they dive into traditional esports is they’re going to look to the same way that they buy, measure, and report on all their other traditional media buys and sponsorships.

What we’ve seen is a number of companies coming in, both new companies like FanAI, which I happen to be on the board of, or GumGum, which provides media valuation, and even Nielsen, which is coming into the esports world–all of these companies are now providing a lot of the data analytics, targeting capabilities, reporting capabilities, so that these brands and sponsors can now come in, do their media buys, see the valuation, compare it to what they’re doing in traditional sports or in other traditional media.

What you’re seeing with a lot of brands is that the return on the investment in esports is greater than what they see in other types of media buying. It’s that type of measurement, that type of feedback loop that’s going to catalyze the further adoption of esports by a lot of the big brands.

Rachael Brownell: Our poll was, is your company currently doing esports? And you had a variety of options there. It’s interesting here because it’s a sort of tie between, “No we’re not currently doing esports” and “We’re interested in doing esports.” The next one is the folks who have been doing esports for more than 12 months. Basically, what it sounds like is our audience is either thinking about it and not sure where to start, or they’ve been doing it for more than a year. Robb, let’s start with you. Does anything in that surprise you? Do you feel like a lot of people aren’t quite sure where to start?

Chiarini: It’s great. I think what they’re doing is right. It’s what we keep seeing from new people entering the space. They’re doing research. They’re listening to webinars, jumping to conferences, having meetings. They’re learning and trying to understand the space. Because again, we use “esports” as this bigass title, right? [laughs] It’s a lot of micros, a lot of things. It depends on what game, what publisher, what team, what organization, what region. There are so many different layers that for someone going in they just get inundated. It’s crazy. You hit a wall and don’t know where to start.

I think that people joining these kinds of things, listening in, getting some perspective from different points — from publishers, from teams, from different partners and sponsors that are already in their space, from technology brands, all the different groups that are out there — is great. This is what we see all the time.

I can’t tell you how many times I go to a conference and I have a group of people who come up to me and say, “We don’t do anything, but we’re interested. We don’t know quite where to start. Where do we go? We’d like to talk a bit.” They’re just learning. So this is totally expected and totally appreciated. I’m glad they’re doing that. This is the group of people I want to talk to the most. How can we help them find their way in this space, create some meaningful activity, and be able to expand on that? We just want to help educate.

Brownell: Jonathan, two questions, really. It sounds like a lot of people are interested in esports, but not everyone knows how to make money doing it. Unless we’re all millionaires, we can’t usually undertake to do things unless we can fund them. Are these results surprising to you? Do you have a recommendation for folks that are just starting out?

Singer: No surprise here, but–there were some questions that popped in that I’ll tie to what you just asked me. Someone said 20 percent penetration of ad blockers for gamers seems very low. Who provided that data? That was actually the general population. We can assume that with gamers it’s going to be higher. Another question was, what can we do right now to make money?

If you’re not in the position to go out and buy a team or sponsor a team, then there are three different things that you want to be thinking about to go in and provide differentiation and make money out of esports. Those are relevance, value, and choice.

Above: Riot’s European competition for League of Legends.

Relevance gets back to that ad blocking conversation and what Kent said. Advertisers here are relevant. They’re in the right place. They’re hitting the right people. But gamers are going to have ad blockers installed. What can you do to change their minds? How can you reach them if you know ways to make your advertising more relevant to who someone is at that point, and not the boots they bought last week that you’re going to market to them again? If you can make the ads more relevant — if you’re in that space — you’re in a good place to address the rapidly growing esports market.

The second piece, value, is what Robb alluded to earlier. We can provide people with in-game perks. We can provide people with in-game currency. There are companies like Sliver.tv that are providing similar things as perks just for viewing. If you’re in a place where you can use a new technology like blockchain to really track what people are doing and help reward viewers for consuming your advertising content, or consuming the streaming content itself–technologies and those sorts of business models are another way you can make money in esports.

The third is choice, which we haven’t gotten to, and I’m curious how Kent and Robb are going to react to this. I think I know how Robb will react. That is, are you developing a technology or looking at technologies that allow viewers to engage with the game itself? This gets to the question of, what is an esport? What are traditional gaming models versus what we can do in the future? Can I interact with your game? I said it in our interview. Can it be the Hunger Games? Can viewers pay or vote to change the map that the players are going to play on next? Can they buy bonuses for their team and throw a little silver box from a parachute? Can they do things like that? Is there technology that enables that, or a game that’s going to enable that?

That’s the last piece of what I think is an interesting place to make money. I want to leave that last one out there for Kent and Robb to respond to and say, “That’s a terrible idea” or “That’s interesting.

Wakeford: As you look at technology that interacts with the game, you’re going to have to work directly with the game publishers. Or if it interacts with the streaming experience, you have to create something–there are plenty of opportunities to create extensions on the Twitch platform that enable different engagement models with streamers and players. There’s a great opportunity on the platforms like Twitch. It’s unclear with the game developers, if they’re going to allow third parties to come in and allow you to have your custom loot boxes, dropping Coca-Cola or something else into the game.

The other area, as we go back to the traditional sports model–merchandise is starting to take off. Live events are starting to take off. There’s a whole ecosystem that’s evolving and developing around esports at a very rapid pace. If you’re in those areas, there’s a lot of room for innovation and a lot of room for new brands to come in and provide something that’s unique for the esports audience. I think we’ll see a lot of new companies doing that. As well as some of the traditional companies.

Chiarini: The short answer is, anything is an opportunity. It needs to make sense. It needs to not detract from the game. We’re looking at in-game integrations and yeah, I think we’re going to see more of that. For years, sponsors and people have been getting inside games. You’ve seen different advertisements, from small things to billboards and signs inside a game to all manner of stuff. I think it’s open. It’s just, what does the value proposition look like from both ends? What does that look like for development? How does it change the game fundamentally, if it does? I think everyone’s open to that. It’s just a question of what’s the opportunity, like anything else.

Above: League of Legends World Championship 2017

Takahashi: How does monetization differ between east and west? An audience members asks if there are any regions in the world that are further along with esports.

Wakeford: The three largest markets for esports in the world are China, the U.S., and Korea. They all have different strengths. What you’re seeing in China today is massive viewership across multiple different streaming platforms like Douyu, Huya, and so on. Huge engagement in streaming. You’re seeing multiple esports complexes. These are complexes that are hundreds of millions of dollars to build. They’re popping up throughout China. There’s a huge appetite for esports and live events in China. You’re seeing huge growth in those areas.

In the U.S. you’re seeing higher monetization rates in terms of sponsors coming in, higher CPM rates for media, higher dollars being paid for broadcast and media rights. On the monetization side you’re seeing a lot of strength in the U.S. And then in Korea, esports has been part of the cultural fabric there for a while. You see huge participation in live events, where people go to esports games as a normal weekend event. They’re filling arenas and stadiums.

You’re seeing differing areas of growth by region. If you’re an esports team–we happen to have offices in Shanghai, in Seoul, and in Los Angeles. We’re diving into all three markets. But if you’re an esports team, depending on what market you’re in, you’ll want to lean into these different growth areas that are happening in the different regions.

Chiarini: I would totally agree with those points. China brings a huge viewership. Korea, the history, the fabric you mentioned, the DNA of that ecosystem. The U.S. is traditionally the money. It’s the market that everyone is interested in, the consumer market. It’s lucrative as far as partnerships and sponsorship. There’s a history there for how traditional sports do things, so there’s a lot of commonality there.

After that, looking at Europe, just the desire of wanting things and doing a lot of cool innovation–there’s a lot of desire in the EU to do new things. As far as regions go–at the end of the day it’s all based on where and what is going on for that game. If you’re looking at the micro level, what’s going on with a game? How do you as a brand or a group as a team feel that going into a market makes sense? If you’re an esports team that’s strong in Europe you might look at Latin America as a growth opportunity, because that’s strategically important to you.

I would say that even though there are varying degrees of regional success, there are still opportunities because of digital content, because of the consumership of those things. There are plenty of options.

Takahashi: We have another audience question here. Are there any companies you think are doing an awesome job with esports? What are some things you can admire in some of these companies that are pioneering?

Singer: I think I mentioned Sliver.tv earlier. They’re doing some cool things around providing value for the viewers. There are others out there, but that’s the first one that comes to mind. Then there’s a company called Genvid that’s doing interesting things as far as player choice and getting involved with the content itself. Allowing spectators to interact with esports content. Those are two of the ones immediately pop into my mind, apart from all the giants out there that are producing the games people love to play.

Wakeford: Speaking of one of the giants, I think you have to recognize that Activision Blizzard is doing a phenomenal job in terms of what they’ve done with the Overwatch League. They created the gold standard of what leagues look like as far as infrastructure for the teams, the best-in-class guidelines for all the players, bringing in sponsors, media rights, innovating in how they’re broadcasting, moving to a regional system. They’ve really pushed the ball forward, so to speak, in growing the esports ecosystem.

Above: Fnatic at the League of Legends World Championships.

Takahashi: We may be able to squeeze this one in as well. What’s the current landscape and relationship between individual esports athletes and corporate sponsors? Are there core management firms popping up to represent athletes? Are team owners handling sponsorships, or are athletes handling business relationships themselves?

Wakeford: As a team owner–there are a number of agencies, esports agencies. They’ve been acquired by larger agencies, so now UTA owns one of the larger esports agencies, as well as ICM. Those are also agencies that represent celebrities and musicians and so on. There are big agencies representing esports players.

For most of the sponsorship agreements, they’ll usually come through the teams and sponsor players as part of the team organization. In some cases you’ll see players outside having their own independent sponsors as well. But today, a majority of the sponsorships are flowing through the teams to the individual players.

That’s very different in the context of streamers like Ninja, who are out there with their own agents and managers securing their own sponsors. But for the professional team players, the teams are playing a big role today as it relates to sponsorship.

Takahashi: One company I just read about that raised some funding was Matchmade. They’re match-making with individual esports streamers and brands, getting sponsorships for influencers.

I think we’re just about out of time. To wrap up, it might be good to ahead a year or two at what you expect for esports and what’s coming next. What’s coming next for monetization? What’s the form of monetization that will kick in in a big way in a year or two?

Singer: Anything that makes esports different from traditional sports, I think, is what we’re going to see more of. That’s in how they engage with their communities and the technology that they use to provide events and provide services? That’s what I’ve been poking at the other panelists with throughout. I think that’s one of the big ways that the market will continue to grow. We’re looking forward to seeing continued growth and more cool events.