At GamesBeat, we like to focus on the business, innovation, and technology of games. So we’re bringing that approach to our games of the decade list. You won’t find just a list of the games we thought were the best from a critical standpoint (sorry, as much as I love you, Obsidian Entertainment, Pillars of Eternity isn’t here). What you will find are the games we believe tell the story of this decade’s industry, setting up where we believe gaming will go in the 2020s.

When we consider the games that define the 2010s, we must look at the 2000s, for three of the games that frame the decade’s innovation, be it in design, economic models, or technology: Dwarf Fortress, League of Legends, and Minecraft.

The mechanics of one of these would filter into a number of genres, and believe it or not, it still hasn’t seen its first retail release. Another would redefine both strategy games and esports, building a massive company, following, and genre … and paving the way for Riot Games to thrive in the 2020s. And our final pick helped usher in the user-generated content revolution of this decade, turning mod makers on PC into well-known names in a community that numbers in the millions … and showing, for the first time, that the idea of a walls were falling down around the game industry.

Please enjoy this journey with us, and again, thank you for supporting the independent journalism of GamesBeat and VentureBeat. We do not have a corporate owner. We’re our own thing, and that you take the time to read us and support us means more to me, Dean, Jeff, and Mike than any of you will ever realize.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

–Jason Wilson, GamesBeat managing editor

Late 2000s: A decade’s foundation

Dwarf Fortress

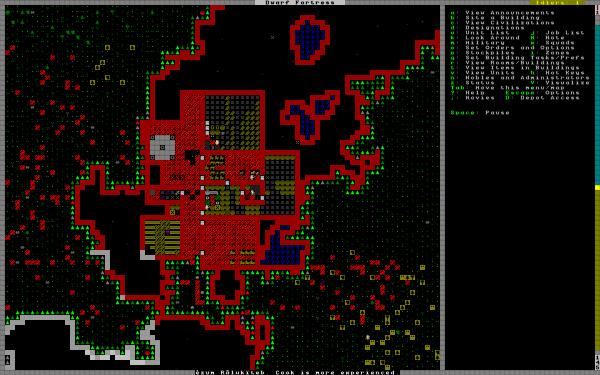

Above: There’s an entire dwarf civilization in those ASCII characters.

Dwarf Fortress’ initial release on the internet was years before the 2010s, and its full publication on Steam won’t happen until the 2020s. Yet it’s been one of the defining games of the decade despite this, alongside other 2000s games like Minecraft and League of Legends. The idea of the living game, one that resides on the internet, where content is continually added, and fans of the game can play it for years, has been possibly the biggest story of the 2010s, from mobile to blockbuster games.

That’s not the only way that Dwarf Fortress helped define the 2010s. “Losing is fun” went the tagline, which is a way of saying it’s a game about stories. It’s a game that’s as or more fun to experience other people playing, whether on forums, or via social media, or streaming. The 2010s were also about games becoming a group experience, blurring the lines between player and viewer. The rise of the roguelike generally, and survival strategy specifically, are directly tied to the idea of games as a shared experience.

Perhaps more than anything, the fact that Dwarf Fortress, a legendarily weird game, could end the decade being one of the most wishlisted games on Steam shows that the idea of what a game is — and especially what a hit game is — has changed dramatically. At the start of the decade, you’d go to a store and pay $60 for a box with a completed game inside was still a default understanding of how games worked, with digital distribution starting to open other models up. By the end of the decade, that door is wide open, and what it means to have a hit game has totally changed. — Rowan Kaiser

League of Legends

Above: Welcome to the League of Legends jungle.

I remember the first time I saw Riot Games’ League of Legends in 2009. I had no idea what to make of it. It was confusing. It was different. And I knew that I was looking at something that would change the way we play strategy games.

But I had no idea it would revolutionize esports as well.

Before League of Legends, strategy games came in two stripes: real time, where you’re building your bases, gathering resources, and constructing an army as your opponent does the same. You scout, you probe defenses while coming up with a plan of attack, and you may also deal with some neutrals running around the map. You might even have hero units as well Or you played a turn-based game, which comes in many stripes, may have you working on economies, social agendas, and more as you build up a grand civilization, researching tech-tree upgrades, and so much more.

Warcraft III’s Defense of the Ancients mod took all of this and made something new, something different, in 2003. And while others beat Riot into turning this style into a full game, Riot was the first to emerge with a smash hit. And we’ve seen League ripple through the game industry. Valve and Blizzard followed with their own takes, a genre we’d come to call MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena). A host of others followed, with many of them failing. The rush came to mobile, with varying degrees of adaptation and success. New twists emerged, such as Clash Royale (combining MOBAs and card games), and it later gave birth to a new genre that’s on the rise at the end of the decade — the auto-battler (think Auto Chess, Teamflight Tactics, and its ilk).

And as League of Legends gained traction, it found players … and Twitch. Here, it continues to be a dominant force. Every day, tens of thousands of people watch top players defend the lanes or push for the goal. And as this viewership grew on Twitch, it changed esports. Before, competitive gaming was the realm of StarCraft and South Korea, along with Evo and a host of smaller fighting game tournaments. But as League of Legends grew, so did its competitive scene. And folks then realized that these viewers represented millions in untapped dollars.

And thus the esports revolution was born, and the likes of The International, the Overwatch League, and a host of competitions for card games, shooters, and other MOBAs. — Jason Wilson

Minecraft

Above: Blockception’s Whiterock Castle was the No. 1 best-seller on the Minecraft Marketplace two months in a row.

I don’t play Minecraft. My kids do. Every day they get video game time, they spend some of it playing Minecraft on our Nintendo Switch. And what they create is amazing — castles, forts, houses and farms. And as they create, they talk about what they’re doing, trying to figure out how to get the designs from their imagination on the screen.

Now, that alone makes Minecraft innovative. We’ve had builders before, but none of them could match Minecraft in its limitlessness. Earlier in the decade, I remember how so many publications covered the amazing creations folks were making inside Minecraft. Someone did a computer in the game that works! And as Minecraft expanded, it knocked down the walled gardens, coming to just about every device that runs games — be it a PC, a home console, or a smartphone or tablet. I’m kinda surprised the screen on my fridge isn’t running it yet. With more than 176 million copies sold, Minecraft’s expanding to other genres and augmented reality.

But it’s done more than knock down walled gardens. In doing so, it heralded how corporate parent Microsoft was looking to get its games on new platforms. But it also showed a new way creators could make money — selling things they make in the store. It built on how folks were selling hats and other materials for games like Team Fortress 2 on Valve’s Steam PC store, and now, people are selling millions of dollars worth on content there.

Minecraft shows how giving people the tools to create and smashing those walls between platforms can pay off not just for a corporate parent — but for everyone. — Jason Wilson

2010: A decade launches

Super Mario Galaxy 2

Above: Mario and Nintendo are at their best in Super Mario Galaxy 2.

In 2010, many of us were still in the middle of the PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Wii era. It was a time of transition. The Wii was a huge success, but it was becoming apparent that its motion-control focus was not going to be the future of the industry, especially with casual gaming taking off in the mobile world.

But for console players, one game defined 2010 better than any: Super Mario Galaxy 2. That may seem like a strange claim. In many ways, Super Mario Galaxy 2 is a safe sequel. It looks and plays a lot like the first Super Mario Galaxy.

Galaxy 2 is just better in every way. Nintendo gave a master class on how to create a traditional sequel. The levels were more creative and the experience was tighter. Even today, when it comes time to praise a sequel, you often hear people compare it to Super Mario Galaxy. And in the midst of the Wii era and stuff like Wii Fit, Super Mario Galaxy 2 reminded us that few are better than Nintendo when it comes to making fun video games. — Jeff Grubb

StarCraft II

Above: They should make a movie about what happens when you teach an A.I. how to fight a war.

Before it came out, you would have thought that StarCraft II would be one of the biggest hits ever. Instead, it did fine. Blizzard Entertainment’s real-time strategy game sequel showed us how times were changing. The original StarCraft was a dominant force in the world of esports, but MOBAs like League of Legends had taken over. This set a trend for RTS for the rest of the decade, as the genre saw a huge decline in the 2010s. — Mike Minotti

Red Dead Redemption

Above: The beauty of Red Dead Redemption.

Red Dead Redemption could be the most impressive game of the PlayStation 3/Xbox 360 era. Its detailed world, convincing acting, and engaging story set a precedent for triple-A games ahead of the launch of the Xbox One and PlayStation 4. It’s still a standard that few have matched. — Mike Minotti

2011: Indelible influences

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

Above: The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim sure caught on.

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim was omnipresent throughout the entire 2010s. Bethesda’s role-playing game came out early in the decade, and we’re still talking about it.

For one thing, it’s very good. Skyrim offers players a giant, detailed world that’s worthy of exploration. It began to influence other open world games, even The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and the VR game Asgard’s Wrath.

And then there were all those ports. Skyrim was originally out for PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and PC. Throughout the decade, it would come to PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Switch, VR, and even Amazon Alexa (well, kind of). — Mike Minotti

Dark Souls

Above: Come, sit by the fire and warm your Dark Soul(s).

Skyrim wasn’t the only game we talked about during the entire decade. While its predecessor, 2009’s Demon’s Souls, was technically the first in the series, Dark Souls established a new kind of action-RPG formula that focused on slower combat, tough boss fights, and punishing penalties for death.

And just like with Skyrim, Dark Souls would come to every platform imaginable. But while Bethesda has been slow to make a sequel for Skyrim, Dark Souls turned into a trilogy in the 2010s, and developer FromSoftware used its formula to make other hit games: Bloodbourne and Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice.

Dark Souls would prove influential, as even Star Wars looked to it for inspiration in 2019 with Jedi: Fallen Order. In the 2000s, action role-playing games were all about fast-paced fighting and combos. Dark Souls changed that. — Mike Minotti

2012: Midsized merit, a galactic riot

Crusader Kings 2

Above: Crusader Kings II is one of Paradox’s breakout hits.

By all logic of how video games should work before 2012, Crusader Kings 2 was a disaster. Here was an incredibly niche strategy game, well outside the Civilization or RTS style that made for a hit, and in its first month? It sold a mere 20,000 copies. And yet, persistence across digital distribution, word-of-mouth, and good reviews kept Crusader Kings 2 going. This game’s combination of strategy and character relationships was special. And that specialness … was rewarded, eventually, as CK2 became a hit and an inspiration.

If any game exemplifies the Steam era of PC gaming, it’s hard not to pick Crusader Kings 2. Beyond that constant availability, Paradox kept it alive by keeping it alive with expansions, add-ons, and patches. The new model for the living strategy game wasn’t a giant expansion or two then a sequel, but a steady flow of new content with new ways of playing the game, and patches to support the people who weren’t buying. The model proved sustainable as well — Paradox used variations on it to prop up both their publishing and their development sides, becoming an ideal form of the new middle class of PC gaming enabled by digital distribution. — Rowan Kaiser

The Walking Dead

Above: Clementine is one of the decade’s best characters.

Crusader Kings wasn’t the only “middle-class” game to succeed in 2012, a year that also saw the release of Telltale’s The Walking Dead. The adventure genre, long-dormant in the mainstream, got new life with The Walking Dead’s moral choices, major intellectual property, and most important, the connection of those choices with an episodic release structure enabled by digital distribution. Telltale itself would become a cautionary tale more than Paradox’s success, but both companies felt a rush of success in 2012 because they used digital as more than simply a distribution method, instead seeing it as a way to creatively develop new types of gaming experiences. — Rowan Kaiser

Mass Effect 3

Above: Mass Effect 3 is an intersection of the decade’s trends.

Also in 2012, we have Mass Effect 3, which is unfortunately best known for its grand ending controversy, a firestorm of fans, press, and developers converging into an absolute mess of internet culture. This masks that ME3 is a great game. But also lost in the storm and fury was that the game’s multiplayer, a remarkable critical success, was also a remarkable success monetarily, as EA started added FIFA Ultimate Team-style lootboxes to more and different kinds of games.

2013: A tale of tails

Grand Theft Auto V

Above: GTA Online changed Rockstar game-development model.

Grand Theft Auto V was a massive game in 2013. And everyone knew it would be. What we didn’t know is that in 2019, it would still be a massive game. GTA V is an enormous success due in large part to the GTA: Online mode. This takes the gameplay into a shared multiplayer world where you can compete in quests, do online heists, and purchase digital items with a currency that you can get using real money.

I think the best way to put GTA V’s success into context is like this: During the decade leading up to 2013, Rockstar released one major new game per year. That included Manhunt, The Warriors, Bully, Manhunt 2, Grand Theft Auto IV, Grand Theft Auto: Chinatown Wars, Red Dead Redemption, L.A. Noire, and Max Payne 3. But since releasing GTA V in 2013, Rockstar has only released one game, 2018’s Red Dead Redemption II.

Instead of putting out new games, Rockstar began working on new content for GTA: Online. That content is cheaper to produce because the studio is mostly just adding new stuff to a gameplay and design infrastructure that already exists. And unlike a new game that might make a lot of money on its first day of release, GTA: Online makes a steady stream of revenue. This makes tricky things like revenues and staffing needs much more predictable and easier to manage.

Maintaining GTA: Online with regular updates is a much less risky proposition than making a new game. And that is GTA: Online’s legacy — especially in the 2010s. Every game developer and publisher wants their own GTA: Online. They want a game that can last for years with regular updates that brings in a steady flow of money. And based on its popularity and the popularity of other live-service games, it’s what consumers want as well. — Jeff Grubb

Dota 2

Above: Dota 2 reaps the benefits of the live-service model.

In the same way that Rockstar made fewer games after Grand Theft Auto V, Half-Life developer Valve has made very few new games since launching Dota 2 in 2013 (after a lengthy beta). And Valve’s reasons are similar to Rockstar’s. But we’re including this MOBA because of how it shaped so much of the business of games.

Dota 2 popularized community items that people could design and sell on Steam’s marketplace. This is also the game that introduced the idea of battle passes or premium progressions passes. Players could buy an item called the Compendium that you would earn levels for by playing Dota 2 matches. And that process would unlock items over time. You could, of course, buy levels if you have more cash than time. Now, battle passes are a common feature in a wide variety of games.

The Compendium revenue, however, didn’t just go into Valve’s pocket. Instead, the company contributed a portion to the prize pool for The International. This immediately turned Dota 2 into one of the premiere esports games in the world. Other studios have since mimicked this practice as well. — Jeff Grubb

BioShock Infinite

Above: Elizabeth’s A.I. received a boost from techniques folks use on the pitch and the stage.

In trying to tell the story of the decade, it’s almost serendipitous that Grand Theft Auto V, Dota 2, and BioShock Infinite all came out the same year. They so encapsulate what happened over the last 10 years. Sure, every studio wants to have their own live-service game that generates profits for years. But what is so wrong with the old way of making a game as a product? Well, BioShock Infinite is what is wrong.

BioShock Infinite was the highly anticipated sequel to 2007’s breakout hit BioShock. Developer Irrational Games started work in February 2008, and it took five long years to get the game out to fans. But more than the time, those were also expensive years. The game was so costly that even after selling 11 million copies, publisher 2K Games obviously didn’t consider the game a success.

Suddenly, we were living in a world where a game could sell better than almost any other game and still end up as a failure. Following BioShock Infinite, almost no publisher wanted to fund a massive single-player narrative-based game — especially in a world where mobile games that cost a fraction to make were generating $1 billion in revenues per year. — Jeff Grubb

2014: Shuffling fate

Destiny

Above: Chilling in the tower in Destiny.

Bungie was a superstar developer in the 2000s thanks to its Halo franchise, but this decade saw the studio leave Microsoft and its first-person shooter series behind to start something new. In 2014, Bungie created Destiny, a multiplayer FPS with MMO elements (what some folks call the “looter shooter,” like Warframe).

Destiny was ambitious, and its release was one of the biggest events of the decade. It was an instant sales success, but Bungie struggled to refine the experience into something players loved. The game would be at its best after the release of The Taken King expansion in 2015. However, Bungie would soon start from scratch with Destiny 2 in 2017. Just like before, it would take work and time — and Bungie separating from publisher Activision to take full control of the franchise — for the game to reach its potential.

Destiny represented the growth of the looter shooter in the decade, something you could see in other games like Warframe, The Division, and Anthem. It’s the kind of experience you just didn’t see before the 2010s. — Mike Minotti

Hearthstone

Above: Hearthstone: Battlegrounds is providing players a new way to play.

Speaking of emerging genres, digital card games weren’t much of a thing before 2014 and Hearthstone became a huge hit for Blizzard, turning the market into a billion-dollar segment. It gave the world a formula for a type of free-to-play game that could keep making money thanks to expansions and new cards. Many of the games it inspired are already dying or dormant, including The Elder Scrolls: Legends and Artifact, but others like Magic: The Gathering Arena are thriving.

Shovel Knight

Above: Shovel Knight Showdown is more Super Smash Bros. than Mega Man.

Indie games were a big deal this decade, but few are as impressive as Shovel Knight. Not only is it the rare retro action-platformer that’s as good as (maybe even better) than the games that inspired it, but developer Yacht Club Games released extra campaigns and modes that felt more like entirely new games than normal DLC. It’s also a great example of Kickstarter’s influence on the decade, as Shovel Knight is a product of crowdfunding.

2015: Community success

Super Mario Maker

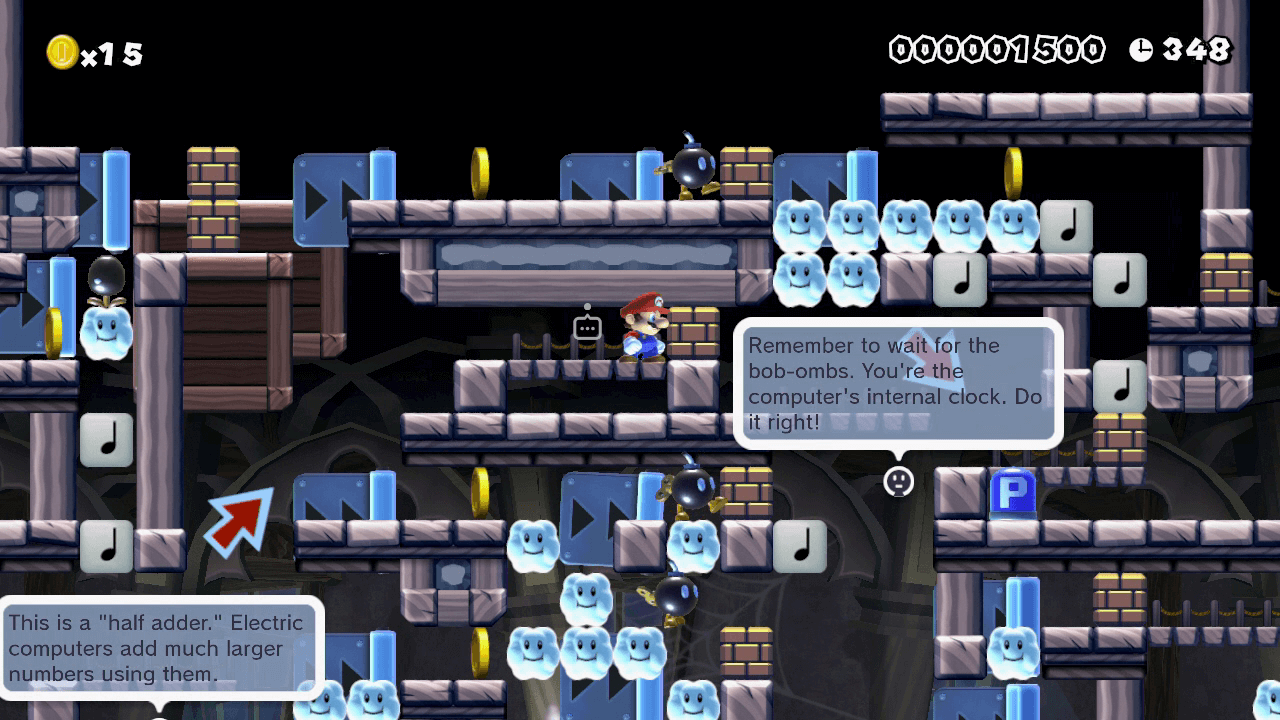

Above: Mario inside the machine!

If there’s a theme for 2015, it’s communities. Super Mario Maker exemplifies this by turning over content creation to players. This is not the first game that asks players to build levels for others, but it is the first game to make the process feel both simple and powerful. Just about anyone can build a stage in Super Mario Maker. The tools are so frictionless that they enable you to get past the basics to unlock your actual creativity.

But Mario Maker also showed how communities grow and spread online. By 2015, Twitch and YouTube were well-established for broadcasting and publishing video content. And Mario Maker showed how games can thrive based on shared communal experiences. When an especially devious creator pushes out a challenging level, you could actually hop on Twitch and watch a streamer try to beat it. And then you could even go and try yourself. It was like everyone was working on a stage together. — Jeff Grubb

Undertale

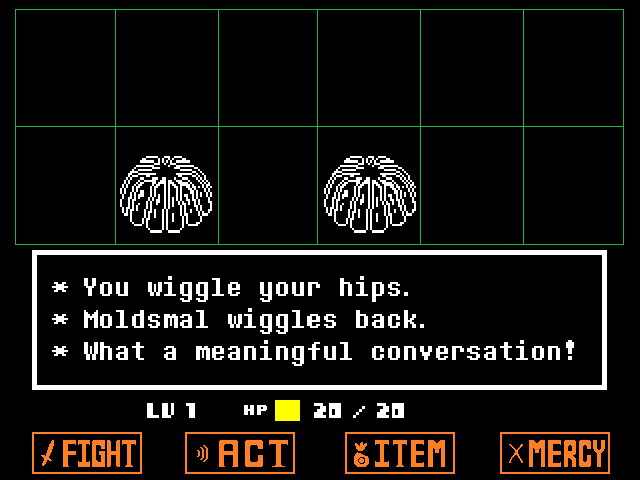

Above: Sometimes you’ll have to get up close and personal with monsters.

The megahit indie role-playing adventure Undertale also owes a lot of its success to its community. And like Super Mario Maker, developer Toby Fox made the game explicitly about fans. But Undertale is actually a criticism of people who base their entire personality around their fandoms.

And yet, the story of Undertale’s success is about a rabid fanbase pushing the game to a mythological stardom. It has dozens of fansites. Countless Tumblrs sharing memes. Thousands of works of fan art on Deviantart.

And while Undertale is proof that indie games can create a Nintendo-like fervor, it’s also representative of the democratization of development. Toby Fox made the game almost entirely on his own using off-the-shelf tools. So even as Undertale turned into a blockbuster success, other creators feel like their games are getting lost in a crowded sea of smaller releases. Over 9,000 games launched on Steam in 2018. So Undertale and other games are feasting, it’s a famine for most other studios trying to break into the business. — Jeff Grubb

2016: Mobile rises

Pokémon Go and Clash Royale

Above: Pokémon Go was the first big step for AR.

Mobile games started the decade as the most laughable of game markets, and they ended it with revenues of $68.5 billion a year, according to research firm Newzoo. Games such as Clash of Clans, Clash Royale, and Pokémon Go generated billions of dollars in revenues and engaged huge numbers of players — many of whom would never pick up a controller or play a PC game. Supercell’s success gave it a valuation of $10 billion, not so far from the $13 billion value of Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption owner Take-Two Interactive. As mobile dwarfed the console business on a global scale, it raised the question of whether it was better to invest money into a successful mobile game company than an old school console game maker.

Niantic’s Pokémon Go got players off the couch, getting them to walk to attain goals and engage with friends. These games defined the decade, introducing new ways of playing, new ways of socializing, and new business models for the West such as advertising or in-app purchases in free-to-play games. And by the end of the decade, Apple sought to change the mobile game business even more with the subscription-based Apple Arcade, and hypercasual game makers such as Voodoo tried to hook players on mobile games that took 30 seconds to a minute to play and went viral for maybe two weeks. Overall, mobile was the most successful new expansion of the game business onto new platforms during the decade.

In 2018, mobile gaming became the biggest segment in the industry for the first time. And unless there’s a major change in either business models or regulation of free-to-play games (regulators are looking hard at loot boxes, a staple here), the mobile market will continue to reign. — Dean Takahashi

Overwatch

Above: Overwatch is famous for its seasonal content

Blizzard created a team-based FPS that was a true successor to Team Fortress 2, one of the most important games of the 2000s. But Overwatch also stood out for its diverse, charming cast. The game also popularized loot boxes, a monetization that became a big craze … until fans revolted against them. — Mike Minotti

No Man’s Sky

It’s usually triple-A stuff that gets the most hype, but Sony positioned No Man’s Sky, from the small team at Hello Games, as a big deal. People were going crazy with anticipation, which lead to disappointment with the release version of the game. Hello Games would then start creating patches and updates that won back the hearts of players. — Mike Minotti

2017: A sea change

Fortnite and PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds

Above: “You can’t handle corporate synergy of this magnitude.”

You probably guessed this one. Battle royale is everywhere in 2019. It’s in Tetris, Forza Horizon 4, and Civilization VI. But the idea of a last-player-standing deathmatch featuring up to 100 different players came to prominence in 2017 with PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds. Brendan “PlayerUnknown” Greene developed the concept of the mode as mods for other games before designing Battlegrounds as a standalone take on the experience.

PUBG was an instant hit in early access in March of that year. It was obvious to everyone, as it set records for concurrent players on Steam, that the battle royale concept had a lot of potential. The appeal is in just how easy it is for anyone to instantly understand. PUBG doesn’t have complicated scoring. The goal is just to outlive everyone else. Whether you are playing or watching someone else on Twitch, you know the stakes. And you know what needs to happen to win.

The appeal was especially obvious to developer Epic Games. That company took the PUBG concept and applied it to its waved-based cooperative multiplayer shooter-builder Fortnite. Once Epic combined last-player-standing mechanics with Fortnite’s colorful, easy-to-parse visuals (and gave it all away for free), it blew up into one of the biggest phenomenons of all-time — let alone the decade.

Fortnite would adopt the premium battle pass to avoid the much-hated loot boxes. This would earn it hundreds of millions of dollars. And that would turn nearly every other live-service developer onto the idea of charging players to participate in a Skinner box.

Two years later, battle royale is still one of the biggest buzzwords in gaming, and both PUBG and Fortnite get the credit for that.

Star Wars: Battlefront II

Above: Star Wars: Battlefront II — the game that turned the tide against loot boxes.

You know what they say: the gaming monetization strategy that burns twice as bright burns half as long. I’m of course referring to loot boxes, and only one game is worthy of telling the history of business model in the 2010s. Star Wars: Battlefront II’s launch was a debacle, and that all came down to the raging hatred that fans have for the loot box.

Here’s the thing about video games: They are expensive risks, and publishers want to get the biggest possible return on their investment. Earning some profit is often seen as a failure because of lost opportunity costs. So let’s think like a publishing executive for a minute. You can sell a game for $60, but that’s just the beginning of the story. Some players are going to wait for a sale. Others are going to buy it used, rent it, or even pirate it. And the result is that the average revenue per player (ARPU) on a game product is nowhere near $60.

So how do you increase ARPU? And keep in mind that there’s no such thing as the concept of “enough” under capitalism. Investors expect endless growth.

Well, gaming is a medium that generates a lot of emotional connections with fans. A certain percentage of those players are people who would spend more money on their favorite game if they could. In the past, that has taken the form of downloadable expansions and a rainbow array of microtransactions.

But why not make these extra purchases a “fun” part of the gaming experience? Like, say, a “surprise mechanic.” And that’s what loot boxes are. They are a way to string players along with the promise of getting some digital items and maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll get the rare thing you’ve been coveting.

Loot boxes give the most dedicated fans a way to spend extra money, but it also gets them into a loop or habit of spending. You’re not really spending your money on an item, which can often feel anticlimactic. Instead, you’re putting your cash toward the chase.

If that sounds exploitative to you, that’s because it is — just like anything that is trying to get you to spend money.

But many people believe that loot boxes cross a line, and the backlash against the concept reached its zenith in the leadup to the release of Star Wars: Battlefront II. That game magnified the issue by attaching loot boxes to pay-to-win items that would improve your character’s abilities.

Gaming fans were so heated about Battlefront II, that the noise began to attract the attention of regulators around the world. And then Disney called up EA and told the publisher to get the spotlight off of the game. Developer DICE pulled the plug on all microtransactions in Battlefront II just days before its release.

And since Battlefront II, loot boxes have gone out of style. They are still in lots of games — especially on mobile. But most major publishers are moving on to premium progression passes instead, and no one is trying to move pay-to-win into new genres.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

Above: Real or madness? It’s all too real for Senua in Hellblade.

Ninja Theory created a triple-A game about a troubled Pictish warrior who traveled to the Norse underworld to save her beloved. The game paid far more than lip service to the topic of madness, as it fully explored Senua’s character and her challenges with psychosis, which included hearing voices, imagining phantasms, and seeing the world in a different way. It’s a triple-A experience that did not stigmatize the mentally ill, treating their version of reality as having real elements. Ninja Theory received hundreds of messages about how Hellblade helped those with mental illness understand themselves, changed how others perceived them, and helped them perceive the world in a new way. — Dean Takahashi

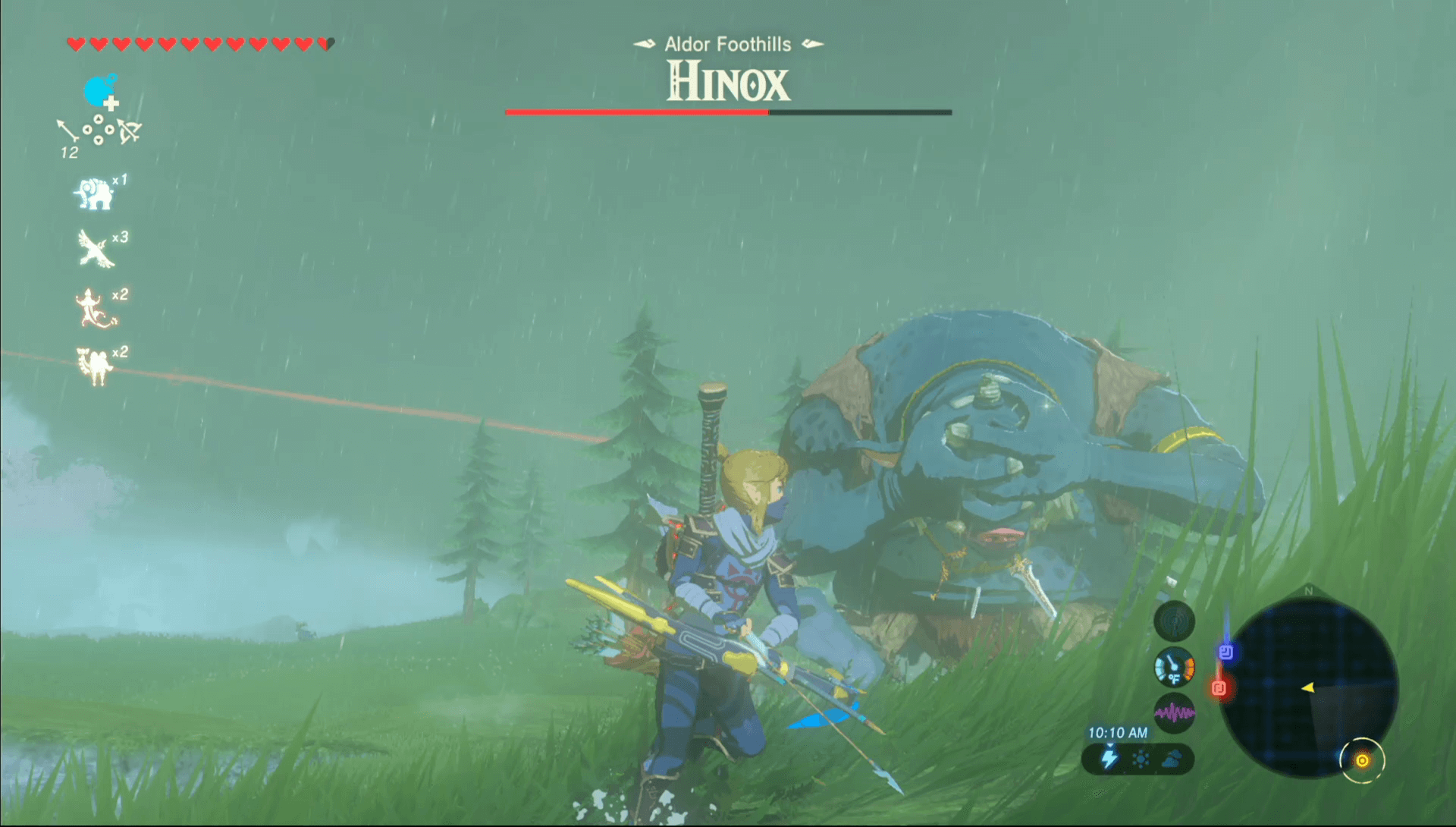

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

Above: Breath of the Wild put Zelda into something new — and we loved it.

Breath of the Wild is an astonishing game. It showed that Nintendo was capable of reinventing even one of its most revered franchises. But this Zelda’s place in the decade comes in showing other developers how to focus on systems. It has a deep “chemistry” system that is a counterpart to its physics engine. This enables things like fire, temperature, wind, and water to have an effect on everything else in the world. And the game opens up players to explore and exploit that system. While it’s similar to similar systems-based games, Breath of the Wild did it with such polish and mass appeal, that it seems inevitable that other studios will try to imitate it.

2018: Triple-A’s big year

Red Dead Redemption 2 and God of War

Above: The blue dwarf provides comic relief in God of War.

Red Dead Redemption 2 had more than 2,000 developers working across a span of seven years, and more than 3,700 people are in its credits. By contrast, Sony’s Santa Monica studio made the God of War remake with 300 people over five years. And in many Game of the Year contests, God of War won. The father-son story of God of War was painful, touching, and moving, whereas Rockstar’s epic Western went on for 105 missions and 100 hours of gameplay with a huge cast of characters. Sony’s tightly focused approach beat out the bloat of Rockstar.

Both games suffered from open world bloat, one of the requirements that executives added to development tasks to justify charging $60 upfront for a triple-A game. But these weren’t open worlds with a touch of narrative. They were far deeper than that, as they had beginnings and endings and plot elements that resonate across so many hours of gameplay.

One lesson of both games is that doubling down on narrative pays off. Gamers grew up, and they embraced deep stories, strong characters, and intertwined gameplay that, when viewed altogether, could be viewed as Oscar-worthy works of art. Every scene of these games could be as impactful as movies, TV shows, and books. It’s a tradition that games reinforced over and over throughout the decade, with games such as Uncharted 2, Telltale’s The Walking Dead, and The Last of Us. In the latter, every melee fight was a life-or-death struggle, and story and character were woven into gameplay. If you fill a room with a bunch of outstanding writers, great things happen. As games grew in this direction, developers could truly say, “F*** the Oscars.” — Dean Takahashi

Astro Bot: Rescue Mission

Above: Astro Bot: Rescue Mission evolved from Sony’s Playroom VR demo, Robot Rescue.

VR was the emerging technology of the decade, and we all kept waiting for that VR killer app from gaming. Astro Bot Rescue Mission is the closest we got, a clever and joyous 3D platformer exclusive to PlayStation 4 and PSVR. Sadly, its quality wasn’t enough to turn VR into a mainstream juggernaut, making us wonder if VR will ever have a true killer app.

2019: A new frontier

The Outer Worlds and Game Pass

Above: The Outer Worlds can be gorgeous.

If we go all the way back to the beginning of our timeline through the 2010s, we know that time isn’t fond of hard delineations. So we can assume that the trends of 2019 are likely going to carry over and define the 2020s. And I think The Outer Worlds is going to do just that. Probably not the game itself. It’s a pleasant spiritual successor to the Fallout series. Instead, The Outer Worlds is important in what it represents for the future of how publishers make and sell games.

The Outer Worlds is important because it is available as part of Microsoft’s Xbox Game Pass service. This Netflix-like gaming platform gives players a library of major games for just $10 per month. And to encourage people to sign up, Microsoft puts all of its first-party releases on the service the first day they go on sale.

And Microsoft owns The Outer Worlds developer Obsidian Entertainment. So The Outer Worlds showed up on Game Pass. Instantly, the millions of Game Pass members on PC and Xbox could download and play the game as much as they want at no additional charge.

This isn’t just some alternative business model. It is the focus of Microsoft’s entire strategy as it heads into the next generation of consoles. And it’s going to change everything.Buying games may quickly go out of fashion. But more important, this may change the motivation behind what games get made.

Microsoft has already acquired a number of studios to produce content for the service. But what will those games look like? It’s hard to predict. The answer is anything that will get people to subscribe and stay subscribed to Game Pass. Right now, we know that is something like The Outer Worlds — a midsized, well-produced open-world adventure that got a lot of positive buzz. But it’s probably going to end up looking like a lot of different games. The subscription model doesn’t just reduce the risk for Microsoft. Consumers can now also try a wider variety of experiences without having to drop $20, $40, or $60.

Look at that in terms of Obsidian’s history, though. This is a studio that gave up working on triple-A games because no publisher wanted to take the risk. Now, Game Pass is providing a way for the studio to make something on the scale of The Outer Worlds every couple of years. But then the studio is even working on a survival game where players are the size of an ant called Grounded. That’s something completely different for the studio because, again, who knows what’s going to move the needle on Game Pass.

My hunch is that when we look back, The Outer Worlds will serve as the ideal example of an early Game Pass hit. But by 2030, that’s going to seem pretty quaint.

Auto Chess

Above: The chaos of a full fight in Auto Chess’ mobile version.

It’s always fascinating to observe the start of a new genre. Out of nowhere, at the start of 2019, a studio called Drodo released “Auto Chess” for Dota 2, a fascinating mix of deck-building, tactics, tower defense, and simple economic gambling. The format was eminently adaptable: Valve made their own, Dota Underlords; Riot, Teamfight Tactics; and Blizzard eventually followed with a Hearthstone variation called Battlegrounds. The format is eminently adaptable to just about any setting with a variety of characters, and the game type is messy enough to allow for lots of different tweaks.

Perhaps it’s a fad, but it seems likely that Auto Chess forms will be around gaming for a while. …