testsetset

Multiple reports say that mobile ad fraud rates could be costing advertisers and publishers billions of dollars a year. That’s a big tax on what will be a $75 billion business in the U.S. alone in 2018 (according to market researcher eMarketer).

That’s why Adjust, a mobile measurement and analytics company, has started an effort across the whole mobile ad industry to fight back. A year ago, the company helped start the Coalition Against Ad Fraud, which is bringing together different players in the mobile ad ecosystem to stop ad fraud from multiple directions.

The group has pledged to tackle mobile ad fraud head-on by working together to develop definitions of fraud, come up with ways to measure it, and talk about solutions that take the incentive out of fraud. The group has now finished its initial document on fraud definitions, and it is trying to spread awareness in the industry.

Adjust also announced the coalition will open up to advertisers to accelerate the anti-fraud efforts. The CAAF initiative is part of a concerted effort by industry leaders like Liftoff, IronSource, and Jampp. The standardization document provides all industry players — including advertisers, supply-side networks and third-party vendors globally — with a common, agreed-upon nomenclature and a rounded technical overview of mobile performance ad fraud so they are better equipped to deal with the issue at large.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Mobile ad fraud can take a number of different forms, from faked impressions and click spam to faked installs. As the industry develops to fight current fraud techniques, the methods used by fraudsters change to become more effective.

I sat down with Andreas Naumann, fraud expert at Berlin-based Adjust, for a lunch recently in San Francisco.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

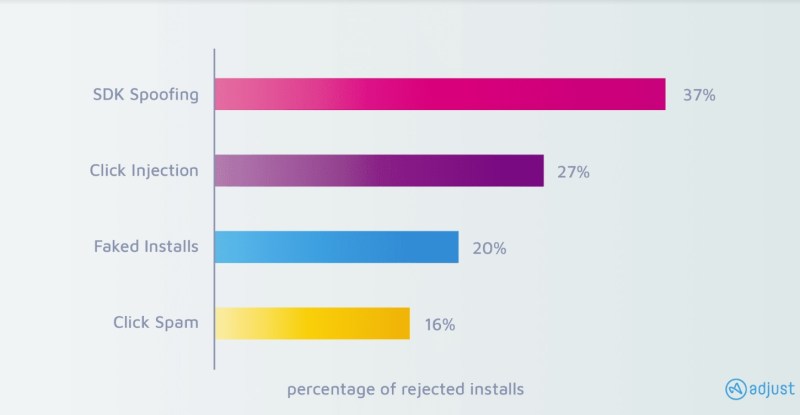

Above: Coalition Against Ad Fraud has defined types of fraud.

Andreas Naumann: We started the coalition a year ago, the Coalition Against Ad Fraud. The idea was that we wanted to get together with the supply side networks to define standards of what is fraud and what isn’t. What’s the methodology of detection? What’s the methodology of mitigation? First, our clients can be sure that we have standards that cover all eventualities in their talks with networks, and also, we can spread that out into the industry for other people to learn and follow. That document is now finished. We’re going to release it on the 18th.

VentureBeat: Were there some major conclusions from that?

Naumann: Not conclusions exactly, but standardization. Nomenclature and definitions so it’s clear what we consider to be fraud, how we find it, and how we deal with it. We have full transparency into what’s going on. There’s so much misinformation out there, so many players who call things different names and say this or that is fraud.

We have the same problems as anyone else. When we started with all of this 2016, it took about three months before all of our competition claimed they were doing fraud prevention, even though they weren’t. They were doing detection, and then clients had to go and get their money back.

Click injections, for instance, was a thing we transparently brought into the market. “Here’s this exploit. We don’t have a solution yet, but this is the problem.” Defining it takes a month or two, and then our competition comes out with something that claims there’s this new thing, calls it something different, and what Adjust is doing is actually the old stuff. They’re just making up new names and definitions for no reason other than to claim that they’ve solved a new problem.

VentureBeat: Who is in the space that you’d consider competition?

Naumann: Direct competition for us would be AppsFlyer, Kochava, Singular to some extent. We’ll see what names they come up with. We just want to make sure that, first off, for our stuff, clients are in the know and can educate themselves. They can bring that into the broader market and share it with different people.

VentureBeat: You guys were putting a number on it in your reports, that it’s a billion-dollar problem?

Naumann: That’s not something I’m so interested in. Except for getting people to click on something to read about it, that doesn’t have any value, really. It’s a large problem, but it’s hard to name how large it is, because everybody only sees what they see. If you have a broad definition of fraud, then maybe it’s a $12 billion problem? But that makes me smile, usually, because as long as you don’t define what’s part of the problem and what isn’t, those numbers are pretty useless.

It gets worse when people start trying to say things like, “Well, fraud is bigger in China than it is in the U.S. by this much.” That doesn’t make any sense. Fraudsters don’t care where a campaign runs. They care about how much money they can make and how little attention you pay to what they’re doing. That’s it. There’s no cause and effect relationship between the country you run your campaign in and how much fraud you can expect.

That’s an unpopular opinion, because it doesn’t make the whole thing easier to understand. But we try to be as candid and transparent about what we’re doing as possible. Usually, when I talk about numbers, I make a big effort to define what those numbers are describing.

We, of course, can only talk about what we’re seeing from our clients’ perspective, but fraudsters know our clients are protected. That’s why they don’t get targeted as much as someone who isn’t as well-educated, who may have older standards as far as KPIs. They may still think about quantity only, acquiring as many users as possible for the lowest price. They’ll see much bigger rates of fraud.

We do a lot of education for the market, which is the background of why we started the coalition in the first place. We want to raise the topic, to educate people in what they need to look out for. Simple steps they can take in order to see if they’re facing the same issues as other players, or if they have to come up with countermeasures of their own.

What’s inherently different is, when we report on, “OK, this is how much fraud we rejected this year,” that’s a much lower number, usually, than if somebody says, “This is how much fraud we detected this year.” If we have actual prevention running — let’s say a client has been running without prevention for a year, and then on January 1 they turn on our fraud prevention suite. They have a lot of sources that do click injections, say, and as soon as they turn their filters on, we start rejecting all traffic that has click spam or click injections going, which means from that moment on, no attributions happen to those sources. They’re not getting paid, and they’ll find something else to do.

In the beginning we’ll see a high fraud rate, which then tumbles right away and stays low. After that, you’ll only see spikes from time to time when someone tries to work fraud in on new campaigns. It makes for an inherently different number than when you detect for the whole month, and then afterward you tell the client, “Hey, you need to get your money back.” That rate will always be higher than when you actually mitigate the problem during attribution. That makes our numbers somewhat incompatible with what the rest of the industry is doing. Nobody wants to do the prevention part.

Above: DedSec is the hacker group in Watch Dogs 2.

VentureBeat: What did you find in the report as far as what types of fraud are growing or being detected most often?

Naumann: You have the classics. Click spam is still really big. That’s any type of fraud where a click gets executed for a user without the user actually clicking on the ad. Those can be completely fabricated clicks that are triggered by a server with device IDs attached to it, or by websites that do ad stacking and automatic clicking on page reload, or any type of app that clicks in the background without the user seeing any ads. Any of those will create engagements that we would attribute, and it gives the fraudster a chance to cash in on the random chance of any of the users they know converting for a popular app.

Click injection is a bit more interesting. The fraudsters here only inject the click after the user has made the decision to download and install an app. There’s an exploit in the Android operating system that allows the fraudster to listen to what’s called the content provider. That makes it available to see which app is being installed from the Google Play store right now. As soon as the user clicks the download button, the content provider has a new entry that says it’s downloading. If fraudsters have a malicious app on that device, they can use that information to inject a click and be the last click, even if there was a legit advertisement in between. That makes for a nice money-printing machine.

VentureBeat: How do you prevent that particular problem?

Naumann: When we found out about this kind of fraud, we got in touch with Google and asked them to help us clear it up. They changed how the content provider works and changed how the broadcasts work. They substituted the install broadcast with what is now called the Google Referrer API. That released in December of last year. That gives a secure referrer data point, and it also has a timestamp of when the user actually clicked the install button in the Play store. [We can model attribution in a way that we do not attribute installs to any engagements coming in after the user made the decision to download and install an app.]

Spoofing is the rising star on the fraud horizon. It’s a much bigger problem. It’s not just an attribution provider or measurement provider problem. It’s a big problem for all advertising. All data communication between an app and the different backend systems the app shares data with is secured by normal SSL encryption, in basically all cases. Fraudsters have figured out how to break open that encryption, read the payload of what’s being delivered, and once that payload is figured out, they can do replay attacks with the same data structure. You just inject different payloads.

For instance, let’s say you have three different phones, and you’re installing the same app on all three phones. You collect the communication between the app you’re installing and the backend systems that are fed with data — the publisher, the app developer, all of that. When you record all of that, you can compare between the different devices, and that gives you the structure of static URL parts and dynamic URL parts. Static is the structure. Dynamic is the data points being delivered in the payload. When you figure out what the dynamic payload is, you can say, “OK, this is the advertising ID, this is the timestamp, this is the device model.”

Once you figure out what needs to go in there, you can either curate data that looks legit and create URL calls that look like the same thing, or what happened a bit later on, you can put a malicious app on a user’s device and use all that device data to create install data points for installs that never happened on the device. You use 100 percent legit device data from a real device out there in the market, so for us it’s impossible to say that this or that install is real or not. We can’t know if this new install is legit or not because all of the data points are 100 percent legit.

The only way to deal with that is to secure the client-server communication to an extent that normal SSL encryption is not the sole security measure. On the MMP level, this is by now a known problem. Our competitors don’t like to talk about it, because their security package for clients, for instance, is only available to people who buy their full product suite. In our case it’s free to all clients, but it’s a hassle to build in. They need to update their SDKs, which is something people don’t like to do.

There are MMPs out there which built a solution that’s close to our first version we built out, but they’re also not actively advertising it. Frankly, it makes attribution providers look like they didn’t do a good job to begin with. Stuff wasn’t secure, now we’ve had to make it secure, and now the client has to move to get to the security level they might have had a year earlier, which would have been really nice.

All the examples I’ve given are between the advertiser and the MMP — the [mobile] measurement partner — and the fraudster. The problem is, this type of communication we use is the same that any other service in mobile uses as well. It’s really just encoded URLs that have a payload. That means the whole spoofing thing also works for monetization SDKs. That’s something nobody wants to talk about.

Obviously that’s a very unpopular thing to talk about. We still do it because we think our advertisers are better off when we explain to them transparently what the problem is and how to secure themselves. Then it’s their decision to do it, which is already pretty shaky. But the rest of the industry just doesn’t want to talk about it, which I think is borderline malicious.

Above: Check Point Software unearthed a mobile ad fraud scheme.

VentureBeat: Is there a way for the advertiser to double-check what is real traffic and what isn’t? They would use you guys, use Kochava, use AppsFlyer, and theoretically you should all agree on the exact amount of traffic. If one isn’t detecting certain traffic — you guys might have the lowest level of traffic getting through.

Naumann: It depends. When we’re talking about spoofing, if the spoofer knows what they’re doing, it’s 100 percent undetectable. All they have to do is put legit device data in the right places and that’s it. It’s indistinguishable because it’s legit device data.

What is detectable is whenever the spoofers make a mistake. But since this is a fraud scheme that’s been around for 18 months now, you can’t expect them to make a lot of mistakes by now.

VentureBeat: If you detect more fraud, though, you’re going to report that the legitimate numbers were lower, right? Is that consistently what happens? You can detect more than the other guys do?

Naumann: It depends on the fraud scheme, again. There’s a couple of things we don’t touch. Unfortunately there’s a strong incentive on the advertiser side to buy fraudulent traffic. If you’re looking for maximum growth, you want to show to your investors that you can buy market share for a decent price. You’re very much incentivized to buy traffic that spoofs the user engagement.

Say you have a real install from a real user that uses your app and spends money within your app, but that user didn’t install the app because they clicked on a banner in a full-stage interstitial. They installed the app because their friend told them about it, or because they saw it on TV. In that case the advertiser or the UA team of the advertiser is cannibalizing the branding, which is cheap. It makes them look good. The performance, in the end, is good. They can claim unlimited growth, and since the branding people can’t make the connection between a TV ad and an install, they lose out.

That can create a deadly circle of mischief. An m-commerce app with designer clothes and so on created exactly that problem. They had a huge branding budget and a pretty decent user acquisition budget for the app, because they were mobile-only. They spent more and more money on the mobile acquisition that cannibalized from their branding, up to the point where they didn’t do any brand advertising at all, because mobile performance was doing so well. Then their organic user influx stopped, so they couldn’t pay as much for performance. There wasn’t anything to cannibalize, any performance to be had. They never got back on track.

VentureBeat: Are there any other big fraud problems to make note of?

Naumann: Spoofing is definitely the biggest one right now. It’s the one that has the least transparency around it. Most of the market doesn’t want to talk about it, or claims it’s not a problem. It’s the hardest to stop. Again, there are no standards. Everybody needs to do their homework. They have to explain to their clients, “We haven’t been doing this for the last three years, even though we should have. Now it’s on you to protect yourself.”

That’s the hardest part. The app developers need to replace the SDKs they have with secure versions. They need to secure their own communications. It’s the same problem for the advertiser themselves. The install data and event data they’re tracking is also at risk. We’ve seen spoofing phenomena where all of our install data was spoofed, and all the advertisers’ install data was spoofed. There was zero discrepancy. Everything looked legit. But actually getting behind that, getting all of that out of the system and figuring out how to secure it, then resetting the benchmarks and KPIs, is a very painful process. But it has to be done.

VentureBeat: The thing I remembered was that Kochava was doing a lot around blockchain.

Naumann: Yes, that’s their new business they want to grow into. I can’t speak for Adjust, but in my opinion it’s not going to do anything about fraud. The idea is, blockchain is inherently transparent and secure, so it fixes the fraud problem. But it doesn’t. It’s as spoofable as anything else is. And it’s slow. I have no idea how they can keep up with the speed they’re claiming. They want to do 100 transactions per second. I’m not sure about that. Their idea is to do it by daily rolling chains, but if you have daily rolling chains, then the actual transparency is not there. You’re transparent for one day only. If I want to check something that’s 30 days old — I’m not sure how they want to do all that. But they’re also not very transparent about how they’re going to do it, so it’s hard to judge.

Above: Percentage of rejected installs, based on fraud.

VentureBeat: You don’t think that’s going to be a big change for everyone in the measurement space, then?

Naumann: Again, personally I don’t necessarily see it, but I can’t speak for Adjust. What they’re essentially doing is saying, “We’re the MMP running the one big exchange,” which I have an inherent problem with. That creates an internal conflict of interest. Who are they going to measure correctly if they’re also governing the whole exchange? Even if it’s blockchain, that doesn’t mean it’s a source of truth. Blockchain is inherently capitalistic in the sense of, whoever puts in the most money makes the most decisions. It’s not a 100 percent secure system from the get-go. It needs to be quite heavily governed. Unless we know how they’re doing that, it’s hard to judge what might come out of it.

In the end it’s just a big exchange that makes you pay in a different currency. I don’t know. I don’t necessarily like the idea of having a service-based currency on any service that I have to use. I don’t know what your take on that would be, but — for instance, I’m an avid gamer. I play PC games and PlayStation games. On Steam I have my Steam credit. On PlayStation I have my PlayStation credit. I can’t pay everything directly with my credit card because everything has to be translated into their credits. That’s very much in their favor.

Do I want to have an ad exchange that has its own currency with fluctuations I need to worry about? Sure, I could make a killing if I buy a million impressions today and in a year they’ve inflated to 50 times their value and I’ve pre-paid for it all. I could make a huge amount of money theoretically. But how does that help me if three years from now, the currency is far more expensive and I have to pay 10 times the price, 100 times? Is that still an exchange that’s useful to me? Not so much.

VentureBeat: You wouldn’t say it’s the best use of their investment money, then?

Naumann: It’s a great way to raise money. If the ICO goes well, that’s a huge amount of money they can use to do whatever they want.

Above: Adjust chief technology officer Paul Muller at GamesBeat Summit 2017.

VentureBeat: What would you be investing more of your resources into now, if it’s not something like that?

Naumann: That would be a better question for Paul Muller, our CTO. I just deal with fraud. One of the things we definitely want to do is what I’d call a transparency offensive. There’s still a lot of inventory out there that’s marketed in a black box, which isn’t benefiting anyone except the guy who holds the black box and earns the money. There’s a lot of fraud hidden in there. We want to take that away by, for instance, encouraging advertisers to only work with fully transparent sources. That’s one thing we want to push through CAAF.

We want to make sure that newly created campaigns come with a couple of rule sets that nowadays are no-brainers. If I want to run a mobile-native advertising campaign, then my campaign doesn’t need fingerprinting. If it’s mobile-native, I’m going to have an advertising ID. Or in the case of iOS limited ad tracking, I’m not supposed to have anything to identify the user by. I shouldn’t even create a fingerprint.

There’s virtually no reason why any display advertisement shouldn’t have an impression attached to it. Anything that’s not a text link has an impression — any video, any interstitial. So why is there 60 percent of the traffic we see coming in without any impression data? The answer is simple: because nobody cares about it, which makes life for people spoofing click engagements so much easier. If there doesn’t have to be an impression, I can make clicks out of thin air. If I create a click, it needs to have an impression tied to it. Then I can push through my impression verification system, because I’m working with verification vendors, and the fraudsters have a much harder time making that user conversion funnel look like anything decent. That’s something we want to take away.

VentureBeat: Do you feel like the big guys are aligned with you on this? Google, Facebook, and Apple?

Naumann: [Some of them are] very approachable when it comes to fraud prevention. They never take our word for it. We have to bring data and prove that we have something. But once their engineers and product managers understand what we have found, they’re super into solving the problems. Anything fraud-related, they want to get it out of their system. There’s a big culture of anti-fraud solution-building with [some of them].