Dementia affects more than 60 million Americans. And today, on Christmas day, many will realize at family gatherings that their elderly relatives have gotten worse at remembering things. I know this well, as my 85-year-old mother has dementia, a loss of cognitive function which causes memory loss and other symptoms.

I’ve been spending some time talking to experts about it, and how we can turn to technology, medicine, or even games to stave off what seems inevitable as our bodies start to outlive our minds. Too often, I’ve found that tech products have been designed without the needs of older people in mind.

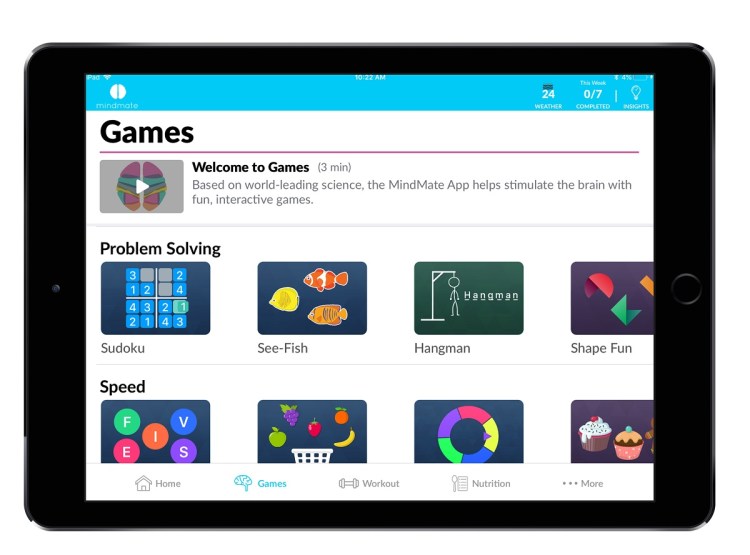

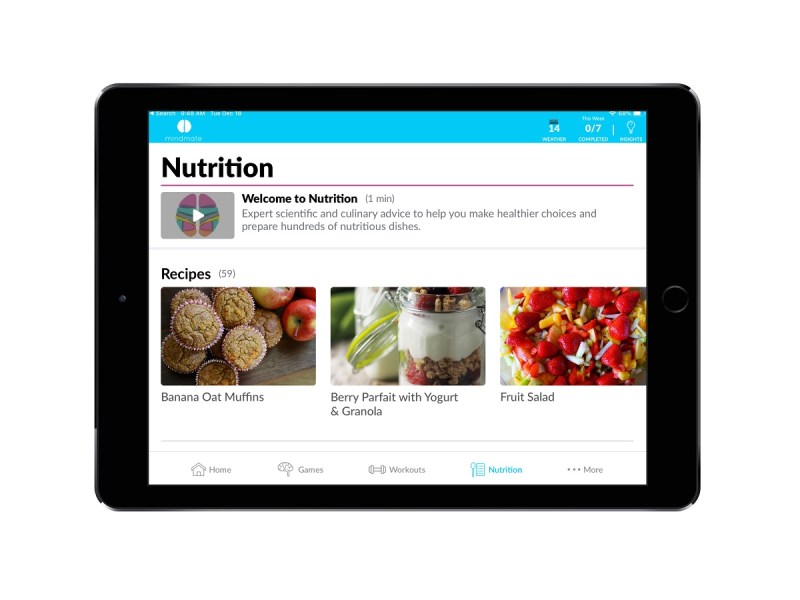

Clover Health, a health care technology company with a mission of helping its members live their healthiest lives, is one of the companies trying to improve mental skills for the elderly. They recently established a partnership with the team at MindMate App. The app combines brain games, healthy nutrition, regular exercise, and social interaction. It encourages its users to make multifaceted, holistic lifestyle changes to help stave off the effects of cognitive decline.

I spoke with Matt Wallaert, chief behavioral officer at Clover Health, about Clover’s approach of using a proprietary technology platform to collect, structure, and analyze health and behavioral data to improve medical outcomes and lower costs for patients. Through its partnership with MindMate, Clover is able to monitor participating member’s app activity and alert the Clover care team of any significant decline in cognitive performance. This can significantly improve health care providers’ and caregivers’ ability to recognize Alzheimer’s, stroke, dementia, and other neurological disorders early, Wallaert said.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

I’m sure that’s interesting for a lot of people. But I had a good conversation with Wallaert, in part because we wandered all over the landscape of what it means to deal with the aging of our brains. I hope you enjoy it, and Merry Christmas to those of you who celebrate it.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Matt Wallaert, chief behavioral officer at Clover Health.

GamesBeat: Tell me more about MindMate.

Matt Wallaert: It’s a company we’ve started spending more time with. We’re launching a little partnership and exploring how gaming can help our members and power some interesting interventions.

GamesBeat: My own mother, who’s 85 years old, has dementia. It’s a very relevant topic for me personally.

Absolutely. I was talking to someone at Clover about this the other day. It’s so relevant as we go into the holidays. This is when a lot of people come home for the holidays and see some of their relatives they haven’t seen in a while. They may not have realized how much has changed since the last time they saw that person.

That’s one of the reasons we’re excited about our work with MindMate. If we can do that early detection, so you don’t show up for Christmas and suddenly realize that she isn’t mentally where you thought she was — if we can detect that earlier on and start to coordinate some of that social support, it can be a real benefit to families.

GamesBeat: How do you do that?

Wallaert,: MindMate is a brain games-focused app. It’s pretty engaging. One of the things I liked — if you look at the average health app, it’s about 3.5-minute session times. They’re not very engaging. MindMate is more like a 16-minute session length, much more like a mobile game.

That entertainment focus is interesting for me as a scientist, because one of the dominant problems has always been how you motivate people to do things. With MindMate, they’re doing the motivation. We can piggyback on the data. People play three to five times a week for 16 minutes at a time. That generates a lot of cognitive data that we can then use to benchmark someone against themselves. We can see if you’re declining over time. That might be a sign that you need to have one of our nurse practitioners have a conversation to check what’s going on as we go along.

The app is pitched like a lot of brain game apps. Memory, reaction time, all of those things people actually like doing on their phones. They’re fun. If you look a lot of modern games, they’re just presentation layers on top of very traditional game mechanics. Those mechanics yield interesting data. The app feels very traditionally like a game, but because games stretch our minds, it does provide good cognitive data.

Above: Dean Takahashi and his mother Hiroko.

GamesBeat: I wonder about gamers’ mental decline over time. Everyone likes to point out that I’ve been playing Call of Duty for years, but my reaction time is so much worse now that I can’t beat the kids who shoot me online. It’s a bit of a digression, but I wonder if that can tell you anything.

Wallaert: It goes in both directions. When you talk about twitch gaming, something like Call of Duty, where reaction time is incredibly important–there are peaks in reaction times. When you look at the science, when you’re 85, you might be able to say that your reaction time is the reason you can’t beat the youngsters. Earlier than that, you may just have other things on your mind besides playing games 24/7.

On the flip side of that, one of the things I love about games, whether electronic games or board games or card games, they have all those mentally protective features. Even if you think about something like bridge clubs, what does that do? It gets you around other people. It gets you talking every day. There’s mental math and accounting that goes into even simple card games. I like pinochle, because I grew up with it. A kind of poor man’s bridge. The cognitive piece can be a protective factor against dementia and other things. It’s the continued use and engagement of your mind.

Games exist along a spectrum. Some games are a bit mindless compared to other games. But being engaged, finding gaming as a place where we can engage people’s cognition, is really exciting.

Above: Humm has a headband for esports biometrics.

GamesBeat: There’s always some kind of hope that my skill can improve. I don’t know how much age matters there. Another digression, I got this headband from another company, Humm, that sends electrical signals into your frontal cortex there. It’s supposed to stimulate your reaction time. I haven’t noticed if it works yet, but it’s an interesting idea.

Wallaert: The thing that’s always interesting about those types of devices — it goes back to the motivational piece. Even if we found something — look, I can’t even get to the gym. There are no things that are good for you that aren’t difficult to get people to do, because they’re uncomfortable, or they take time.

What I love about games is they’re intrinsically engaging. The great thing about working with MindMate is that normally my team spends an enormous amount of time on that motivational piece. How do we get people to want to do something that’s good for them. Games are self-motivating. You want to play. But they’re also quite good for you.

If you take something like MindMate — we have a large machine learning team, and one of their big outputs is something called diagnosis suspecting. How do we take in all the data we have about a person and say, “What might be going on with them that the conventional medical system has not yet recognized?” At this point we’re able to make significant new diagnoses that we can then confirm in person.

We have all these NP/MA pairs that go out. The system says, “Based on all the signals, Matt might be pre-diabetic. When you see Matt in person, have a conversation about diabetes.” Because we have a connection to their doctors, we can also, in the app that we use, tell their doctor: “Hey, Matt might be pre-diabetic, so when he comes in for a checkup have that conversation.”

What we’re working on with MindMate right now is taking in the data from this rich source. I intrinsically want to play games. I don’t have to do anything I wouldn’t normally do. I can just do something that I enjoy. But then that yields data we can plug into a machine learning algorithm and say, “Next time Matt comes in, you should check and see what’s going on. His reaction times are going down. He’s starting to not perform as well at short-term memory tasks.”

It’s that alerting system that — even separate from, to your point, the question of whether these games make you smarter. It’s possible. There’s some good evidence that brain games and staying engaged mentally is good for you. And then on the alerting side, even if you don’t expect the game to improve your mind at all, we can still derive value from understanding what’s happening with you and being able to intervene within the normal clinical system.

GamesBeat: Is there a stage or an age where you think it’s good to get this started, to be able to detect things happening with people? There’s a certain stage where it seems like it may be too late to be helpful, but I don’t know exactly what that might be.

Wallaert: On the detection side, and even on the brain training side, people being engaged at any age is great. We can always make use of that data. You’re right on — at some point, your cognition has declined enough that I don’t think playing games is an effective way of combating that. Although there is anecdotal evidence out there that just being engaged in the world can be quite good.

On the learning side, even if at this point you’re quite demented — if your cognitive abilities have slipped quite far — even the alerting piece is quite good. Recognizing what’s going on with people seeing sudden decline. Even if the game can’t improve you, there are nice pieces to that. In a perfect world, where you and I got to design our Star Trek game of the future — if there was a game that followed you through your whole life, there are some very real potential possibilities there to be able to take longitudinal data.

Think about it this way. If you start playing the game, that’s my first detection point for you. I can watch if you decline after that, for sure, but I don’t have a long history. Whereas if we can get people playing brain games earlier and earlier on, I know what you’re normally like, and I know what you’ve been like for a long period of time. I can detect more subtle changes. The longer the history of data I have, the more subtle the changes I can detect.

Above: The MindMate app encourages good nutrition.

GamesBeat: If you could get any data, what would be your sort of dream data for your purposes here, detecting mental decline?

Wallaert: That’s a hard question. Some of the MindMate data — certainly reaction time is really important data when we start talking about cognitive things. It’s a good kind of canary in the coal mine for other stuff that might be going on. If you think about what happens in reaction time — as long as it’s not purely automatic, the autonomic nervous system — many steps of cognition happen there. Often reaction time to language-based things is really good. Lots of parts of your brain are involved in processing that data. It’s a good end-to-end detection mechanism.

Memory is also good. I love some of the memory games that are available for that same reason. The ability to hold something in mind is also one of the things that — when it goes, it’s not always transparently obvious. Looking at stages of dementia, it can be hard to tell the difference in someone who’s genuinely abnormal, as opposed to the normal forgetfulness we all experience. We all sometimes struggle to remember the name of a song or something. How do you detect those changes?

I will say that in many ways, it isn’t just about the data for me as much as it’s also about the ability to then go intervene. Much has been made of big data. Everybody’s gone and put together giant data lakes and tried to make something out of that. But it’s not helpful if you can’t do something about it. The ability to have an on-premise nurse practitioner and medical assistant pairing that can go out to somebody’s home and say, “Hey, let’s check in.” Having a field outreach team, having close connections with doctors — it’s the full intervention loop that’s really interest. Data alone doesn’t do it.

MindMate has the same data. Intrinsically it has all this data. But they don’t have the ability to send someone to intervene, and we do. That’s why the partnership makes sense. You have to have that full loop. It isn’t just about data for me. It’s about the dream system of being able to take that data and say to a doctor, “We saw this and you should check in on this the next time they come in,” when they might not normally do that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDVUAdxsg7Y

GamesBeat: I interviewed John DenBoer recently. He has this company called Smart Brain Aging and the BrainU online app. It’s a competitor of sorts, another set of games for people with early dementia signs to play. One thing he said was interesting, though. He looked at some of the other games out there, like Lumosity, and he noted that a lot of their games were very repetitive. They would give the player the same kind of quiz each day.

He argued that if you make someone use the brain in a different way every time they come back, that was a positive. You could otherwise see them get into a pattern where they only get better at one particular thing while the rest of their mind could still be in a state of decline. Sort of like, if you do a lot of crosswords you may get very good at crosswords, but your mind might not stay so sharp in other ways.

Wallaert: I’d push back on him a little bit on that one. What he’s talking about, essentially, is the practice effect. The longer you do a task, the better you get at it, for sure. There should be, in theory, for any task — the more we do it, it should go up and to the right. He’s saying that up and to the right might disguise a larger general decline.

But remember, when we talk about something like dementia, we’re talking about a neurological, biological decline. It’s unlikely that the practice effect would mask it, and even if it did, you’re not going to see substantial enough practice increases.