GamesBeat: The masking part may be me misspeaking somewhat. It’s more that the games you play repetitively and the things you use your mind to do repetitively don’t necessarily help you stave off further decline.

Wallaert: Certainly there’s an idea that neurodiversity — the more different kinds of tasks you do may be protective. All of this is still in the very early stages of science. In some ways we’re still the blind leading the blind, in the sense that even neuroimaging at this point — if you’ve ever watched an FMRI or another type of imaging process, we’re in the very early days of being able to detect what goes on in the brain. The brain is a fantastically complicated thing.

You could certainly posit that doing different kinds of tasks might keep you sharper. That seems generally probably true. But I think that sometimes, particularly among people who are really invested in the “games improve your brain” business — they overstate the case or the evidence available there. What’s certainly true is that games are good at recognizing or providing data that might alert us that something has gone wrong.

This has always been — Lumosity makes very bold claims about what they are able to do for people’s brains. But when people investigate those, there’s been more smoke than fire there. That said, again, the detection portion is actually a little bit easier for us to measure, because can say, “Hey, we think we’ve detected a change.” Then we can follow up with more extensive, more in-depth clinical testing and see if that matches the detection we see in the changes in data.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Part of that is just habituation. Computers are good at doing something we’re bad at doing. I’m a psychologist, right? One thing we’re bad at as humans is we habituate. It’s not like Grandma loses her memory all at once. Every day it just gets a little worse. That’s why I talk about the holidays. If I haven’t seen you in a long time and then I see you, it’s evident to me how much has changed, whereas if I’ve seen you every day, I might not realize because the decline is a little at a time.

The great thing about allowing algorithms and data to guide us, that can say, “Hey, you’re not recognizing this, but it’s really happening, and it’s happening steadily. You need to go address it.” It’s that human-AI hybrid that I think is so powerful in terms of the detection portion.

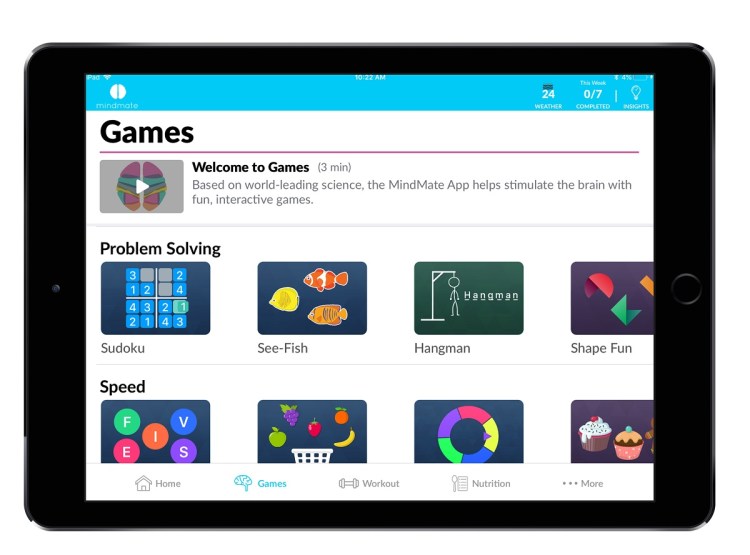

Above: MindMate encourages exercise for older adults.

GamesBeat: As far as more deliberately designing something for this purposes, how is it different from designing, say, a trivia game, something that isn’t necessarily intended for dealing with dementia?

Wallaert: One of the problems of games in general is that they’re often unimodal. They’re based on a central core conceit. Part of the problem of nerve degeneration is it’s short term memory and long term memory and reaction time and, and, and — there are so many pieces to it, and you really do need a suite approach to that. That’s some of what I would see eye to eye with DenBoer on, the notion that you need more than one triangulating point in order to do good detection.

When people try to take data from a unimodal app, it’s a very impoverished signal. Even MindMate on its own, or Clover on its own — it’s the triangulation of multiple signals that helps. Reaction times are slowing down. Memory is getting worse. They haven’t called Clover in the last several months. They’re going to the doctor less but their medical expenses are rising. It’s a whole combination of factors that says there might be something going on and we can do early detection. When people try to just use naturally generated data from games without designing the games to generate that data, I do think there’s often not enough meat on the bone to be able to intervene in a timely way.

GamesBeat: Trivia Crack or HQ Trivia, then, that’s not going to be as helpful as something more deliberate.

Wallaert: Absolutely. Now, I still think we’re in the early stage of what “deliberate” is. I don’t think anyone has cracked the code and figured out that this or that modality is going to be the perfect thing. But we know enough to know that it needs to have a component of reaction time. It needs to have a component of memory. We’ve started to tease those out.

GamesBeat: If you look back into history, are there games that share some of these characteristics? I don’t know if it goes all the way back to Nintendo’s DS Brain Age game.

Wallaert: I remember that one well. There have been — even for the Game Boy there were brain-based games. One of my favorites, actually — if you want to get really old on this, it’s Tetris. It combines reaction time with spatial awareness. I don’t think anyone’s done this, because there’s no way of getting the data. I don’t think anyone’s tried to look at it. But I would bet that Tetris performance is probably a pretty reasonable early warning sign that there might be something going on neurocognitively, if we saw that decline.

Honestly, lots of the games we make for children — this is not meant to imply that dementia makes people childlike or in any way deprives them of what it means to be an adult. But we make games that help push kids’ cognitive envelopes. Slapjack, something that has that reaction time element to it. I have a three-year-old and I watch him getting better and better at memory games, remembering where the cards are and flipping them over one and a time and turning them back. Even if those were designed to push the neurocognitive envelope, they’re inadvertently pretty good tests of neurocognitive things.

To your point, there is some accidental good detection out there in the way we’ve made games throughout history. What I think is new in this area is combining modes of games, and then being able to get data out of them. Something that has the internet as a backbone, smart apps, that kind of thing that can give you the data output. And the real new revolution is then marrying that data to other things. As I pointed out, the data alone doesn’t do a lot. It’s the ability to match that data up to what Clover has — a clinical data set, a stream of claims, knowing when you go to the doctor, talking to you often, seeing you in person. Marrying all that together is where I think starts to get interesting.

The next frontier is starting to involve families more. Not just being able to alert a doctor that you should do a neurocognitive test the next time a person is in the office, but really starting to involve families in the care of older adults as they age, by helping them start to do some of this detection work. Getting their opinions. “Hey, have you noticed anything going on with Grandma the last time you saw her?” Honoring that small data is as important as getting it together with all the big data.

Above: Hiroko Takahashi

GamesBeat: From your experience, is it very helpful to catch this early and to do preventive work? Or is it inevitable?

Wallaert: The perception that it’s all over, unfortunately, is something that makes it worse. As we all know, we’re heavily affected by our own meta-cognitive states, our own feelings. I muse about this all the time. I make my living with my brain. I’m a scientist. I’ve been doing this for a long time. I think about what it would be like if I had a stroke or an accident, something that affected my cognitive abilities, and how core that is to my personality and my identity. It can be quite hard.

When I went to Swarthmore in college, all of my family was back home in Oregon. I was a first-generation college kid. I didn’t really know much about going to college. I was sort of adopted by this older couple that had retired from the college. He was a VP of development. Unfortunately, both of them have passed in the last couple of years. They were so smart and so vibrant for so much of my time with them, and then watching them toward the end, their neurocognitive decline and how that affected them emotionally, was really hard.

That’s actually one of the reasons the MindMate partnership is really interesting to me. I don’t just think it’s about neurocognitive protective factors, although I think those are real. To me there’s also social support stuff. The sooner your family can help you create an environment in which the difficulties you’re having won’t be a danger to you or to others, that’s a great thing. The earlier we set that up, the smoother the transition we can have.

GamesBeat: What about the notion that I don’t have to worry about this for a long time? How early should people start thinking about playing with this kind of purpose?

Wallaert: I think it’s never too early, but what I would say is, that’s challenge to developers. That’s a challenge to game designers everywhere. Hopefully what we get to is a place where you don’t have to play a game that you don’t really enjoy, because you feel like you need to take it like medicine. Instead we create a variety and a diversity of games that meet people where they are, that are based on their interests.

I think about Monopoly. Monopoly comes in every flavor known to man these days. No matter what you’re interested in, there is a version of Monopoly that does it. The core game is the same, but it’s hooked to some cultural element that resonates for you, and that’s enough to get you to play. What’s interesting to me over time is, how do we make enough games in the world that — you don’t have to feel like, well, it’s too early or too late to start. Instead you authentically want to engage with it because it’s fun.

There’s a million registered users of MindMate, and I don’t think it’s off the value proposition of “defend my brain against aging.” These are games. They’re designed for you. They’re fun. The print is large. It’s based on fun. Then the challenge to the rest of us is, can we take the thing that’s authentically fun, authentically motivating, and then add value to it for you? Can we make this thing you naturally want to do something that’s good for you?

I think a lot about laser tag. Laser tag is an amazing way to get people to exercise without thinking about exercise. They play because it’s fun, because they’re with their friends. But if you ever play an intense game of laser tag, you’ll be very tired at the end. You’re running around playing laser tag for an hour, that’s an hour of running. People will do it who would never go running on their own. That’s the attraction of games. How do I want to make something that you just want to do, but that’s actually good for you?