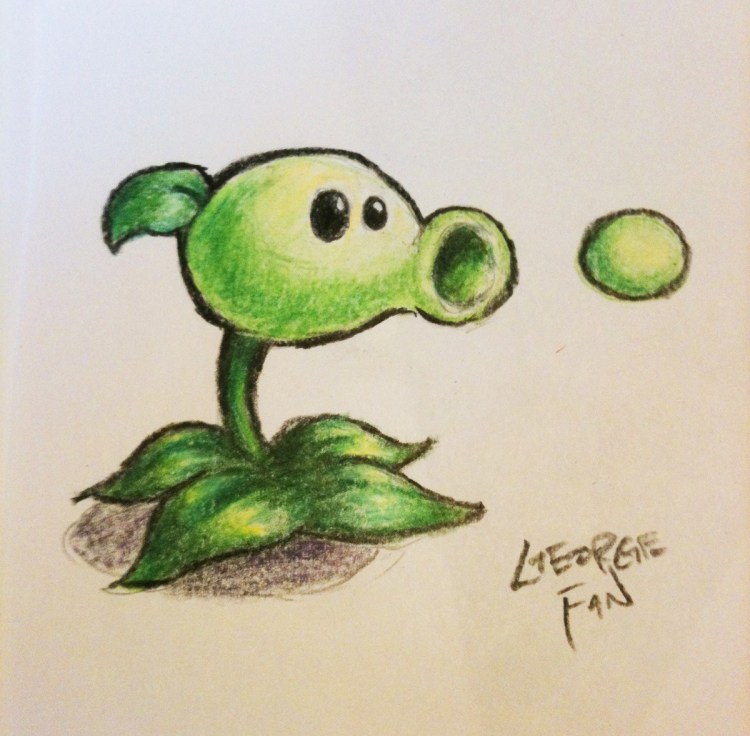

George Fan is a master of zany game design. He created Plants vs. Zombies, the crazy surprise hit that PopCap Games launched a decade ago.

The game became a cultural phenomenon upon its release in 2009, with its oddball sense of humor where plants squared off against backyard zombies in a cartoon style. It was nuts, but it was also a well-balanced, well-designed game that consumed many hours of my life.

And it was also one of the reasons that EA paid more than $750 million to acquire PopCap Games in 2011.

EA hasn’t tallied how many copies Plants vs. Zombies have been sold or downloaded in its lifetime, but it noted in 2013 that the sequel was downloaded more than 25 million times. EA also spun up its Garden Warfare series of shooters, with a new one coming this year.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

But after creating PvZ, its creator stepped back. He chose not to create a sequel to the game. Rather, Fan decided that he wanted to continue working on independent titles. Fan left EA because he didn’t believe in making free-to-play games with microtransactions. He believed in making indie titles, like the Insaniquarium game he made before tackling PvZ.

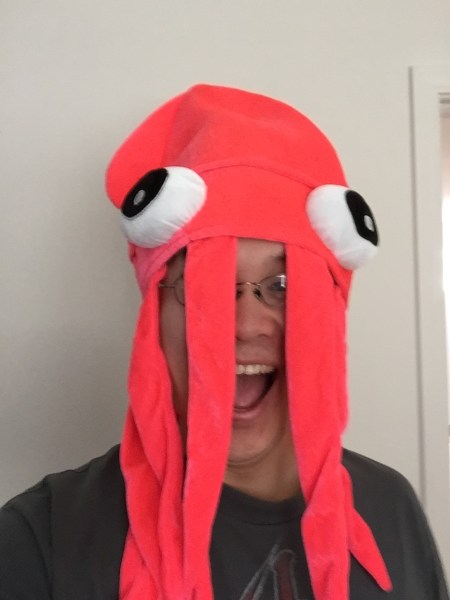

He came up with an idea for a new game during a game jam in 2012. On and off, he worked on it, and last year he debuted the wacky indie game Octogeddon. Fan is now working on a title for Wizards of the Coast, but he is glad he chose his path of working on original titles.

I caught up with him recently for an interview. Among the things I learned: It could have been Plants vs. Aliens. Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: George Fan is the cofounder of All Yes Good and designer of Octogeddon. He also created Plants vs. Zombies.

GamesBeat: We’re at the anniversary 10th here of Plants vs. Zombies. I’m curious what it makes you think about.

Fan: It doesn’t feel like it’s been 10 years. 10 years is a long time. It’s just crept up on me. Whoa, it’s been that long since we released this thing? It’s made me recently go back and reflect on what it was like making the game, what kind of impact it’s had.

GamesBeat: Have you tracked how many copies it’s sold, how many people played it, all that stuff? It must be harder to do that now.

Fan: I haven’t tried, but I don’t know if the people at PopCap would tell me these things.

GamesBeat: I wonder if they’ll do anything to celebrate it themselves, over at EA.

Fan: I haven’t heard anything. We’re taking the helm here and making sure something happens. [laughs]

GamesBeat: What is the actual day again?

Fan: I kept thinking it was May 8, but it’s May 5, Cinco de Mayo. I think the reason I keep thinking it’s the 8th is because someone at PopCap, when it released, made a joke about “Cinco de Ocho,” so I kept thinking it was on the 8th. But I was corrected. I was planning to do this kind of thing on the 8th instead, but someone corrected me. No, you’re mistaken. It was actually the 5th.

GamesBeat: Was that a launch on Steam? What was the actual occasion for that?

Fan: I believe it didn’t come out on Steam until a little bit later. I know it was launched on PopCap’s — remember when PopCap just sold stuff on their site? A few other casual game sites had it too, on the same day. It’s possible that it came out on Steam on the same day, but I feel like I remember we were in talks about that, and that might have happened a little bit later.

I remember being concerned. “We’re selling it for a lot less on Steam than on our main site. Is that going to be an issue?” But they assured me that it’s different audiences, so it would work out fine, and it did.

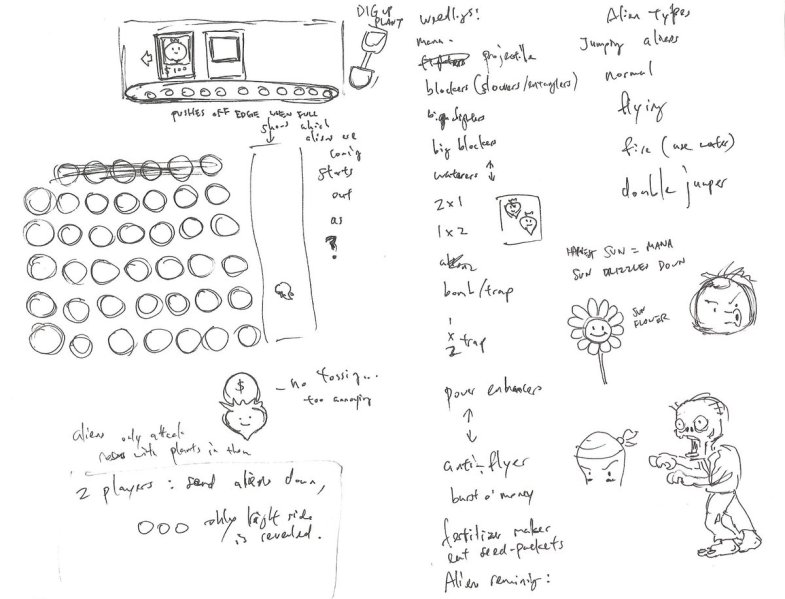

Above: George Fan’s concept for Plants vs. Zombies.

GamesBeat: Going back further than that, can you talk about the origin of it and how long it took to get done?

Fan: The origin came from two angles. It evolved over a period of time. The original seed got planted in my mind about it when — I’ve been a long-time fan of Blizzard’s games. Every single game of theirs that would come out, I’d devour. Naturally, when Warcraft III came out I played that a bunch, but I spent even more time in their custom map system, where players could make their own game modes based on the Warcraft III engine.

One of the things that was popping up a lot that I found myself really drawn to was the tower defense. There was a bunch of tower defense games in the Warcraft III engine. I kept thinking, “Why is this so compelling to me?” It made me think of this movie — I can’t say I watched the whole movie, but as a kid, I would watch the last part of the Swiss Family Robinson, the part where they set up the tiger traps and get the coconut bombs ready for the pirates to storm their settlement. Preparing for the pirate onslaught. That always gave me this unique defense, survival, setting things up feeling.

GamesBeat: I never thought of the Swiss Family Robinson as an RTS.

Fan: Right! Jumping ahead a bit, midway through Plants vs. Zombies I remembered how much I liked the last part of that movie. I thought we needed to capture that a bit more. Part of the coolness is setting up the traps and the payoff. We didn’t have anything extremely like that in the game, so that’s where the potato mine came from. You put it in the ground and then it takes a while, but it pops up later, and you’re anticipating when the zombies are going to step on the mine and explode. That was the direct result of me thinking about the Swiss Family Robinson.

GamesBeat: This was 12, 13 years ago?

Fan: Yeah, right around 2006, or maybe even 2005.

Above: Plants vs. Zombies

GamesBeat: Were you alone at that point, or were you already working with a small team?

Fan: I was working on this alone. I had been working with PopCap. I made Insaniquarium, and they helped me finish the game and publish it. That leads to the other half of where the inspiration came from. I finished Insaniquarium and I started thinking about ideas for a possible sequel to that game. It naturally led me to think about, well, Insaniquarium is about one fish tank. And the Nintendo DS was out right around this time, so I was thinking about those two screens.

Maybe I could make a game about two fish tanks, one on each screen. Or you would alternate between two fish tanks on one screen. One fish tank would be where you ramp up your economy, and the other one would be the defense tank. You’d raise a bunch of fish, like archer fish that shoot at the aliens coming at you. Insaniquarium, the original one, had at most one or two aliens ever attacking the fish tank. I was thinking there’d be huge droves of aliens attacking this time. I don’t know if you can predict where this is going.

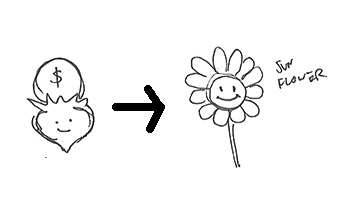

On a sort of tangent, I was trying to come up with a gardening game. You’d pick up your seeds and things. There were originally these tuberous plants that you’d put in the ground and grab a watering can and watering them. They’d sprout and get bigger, and you’d eventually pluck them out of the ground and cash them in for money, repeating that and using the money to buy even more plants. Then you could save up to buy a cabbage-pult, which is a sneak preview of something that’s in Plants vs. Zombies. These cabbage-pults would lob cabbages at an army of aliens. It was going to be in the same universe as Insaniquarium, but the aliens were sick of eating seafood and now they wanted to be vegetarians, so they’re coming after your garden.

Two things played in — the idea of defending against the aliens while tending the garden, nurturing and watering the plants. That felt like a mismatch of gameplay, though. On one side, it just felt tedious to garden while you were trying to fend off the aliens. So what if you just planted the cabbage-pult and it shot right there? That tended to work better. It was more like a traditional tower defense game, where you could build a maze and trap the enemies.

So then it was plants versus aliens. It was called Weedlings at the time. All the plants had little characters, little faces on them. It was pretty adorable. This was back when the casual games industry was booming. Right at the time I noticed a ton of gardening games coming out. I didn’t want to just be another one of the gardening games. I had to stand out. What do I add? I add zombies. None of the gardening games had zombies. Out went the aliens and in came the zombies.

I also redid the gameplay, the lane-based thing. I had that epiphany one day. “Hey, I want to try this out.” That part was kind of inspired by an old arcade game called Tapper, where there’s some amount of lanes of stuff coming at you. I felt like lane-based gameplay had some sort of appeal, so I wanted to try it out. It was plants and zombies.

GamesBeat: When did you think that it actually got fun? During what phase of that development?

Fan: It was right around when I made those last changes. That’s when I thought we were on to something. It was already pretty darn fun. Did I ever tell you the story of why it was plants and why it was zombies, by the way?

GamesBeat: No.

Fan: I’d worked with PopCap and we had the same kind of design philosophy. You want to make your games appeal to as wide an audience as possible, so all kinds of people will play your game. I loved playing Warcraft III tower defense mods, but one issue with those was, the map you were building your towers on was multiple screens wide and tall. You had to use the mini-map in the corner to navigate all that. You’d have scrolling controls, moving the mouse to the edge of the screen to scroll.

When you introduce stuff that’s beyond the immediate scope of vision, it always gets complicated, and you have to add UI to navigate that. I wanted to avoid that altogether. Can I make a game, a tower defense game, that just plays on one single screen? That was the goal.

I needed an enemy that people would just look at and immediately realize, “That’s a slow enemy.” I wanted the enemies to come on screen and walk at you really slowly to give you the time strategize against them. If the game had been Plants vs. Cheetahs, it wouldn’t work. The cheetahs would sprint at you and you wouldn’t have time to set up defenses or put down potato mines in advance. I needed something that was obviously a bad guy, but also obviously slow. That’s why it’s zombies.

The reason it’s plants is because I like to inject as much character into my games as I can. Towers themselves weren’t going to do the trick. Towers are typically buildings with no faces on them. Here’s a wood or metal structure that shoots arrows at things. I wanted something that I could put faces on. I’d played a tower defense game where your towers were these little knights with swords and stuff. They would walk toward the enemy, but when the enemy got out of range, they would walk back to their original location. Why don’t you follow the enemy? That doesn’t make sense either. I was looking for something that satisfied all that, but you would take one look at it and know that it doesn’t move.

What’s something that everyone knows doesn’t move? Plants. That’s why it’s Plants vs. Zombies. It’s not just a coincidence. I didn’t just think, “What would be great to pit against each other? Plants and zombies.” A lot of thought went into each of those ideas.

Above: The original Plants vs. Zombies team

GamesBeat: Do you remember how quickly it took off, or how it went viral? Was it really steady out of the gate, or did it take some extra boosting from any particular marketing direction?

Fan: Going back to a couple of months before launch, there was this game Portal that came out. They had this really catchy song that they played over the end credits. We were all in love with that. We said, “Let’s do end credits where the sunflower is singing a song and the zombies are having a huge dance party.” We flew the artist in for a couple of weeks, and the three of us crammed on it. Then Laura Shigihara, the musician, wrote this earworm of a song. It was super catchy. After we had that song, we were thinking up zombie dance moves to it for two weeks, choreographing this whole end sequence.

GamesBeat: I remember this, but I don’t remember what the song was.

Fan: “There’s a zom-bie on your lawn…”

GamesBeat: Right!

Fan: Yeah, that’s it. Now you remember. So we had this all done. We said, “Okay, let’s watch it again,” and we were all so proud of it. We thought it was the most amazing thing. You’re going to feel super rewarded to beat this game now. Then the marketing department at PopCap saw this and said, “This is the best thing. Can we use this for promotion?” On the one hand, it does spoil the end of the game, but on the other hand, sure, why not? If you really think this is going to be great for getting the word out, then let’s go for it.

We set up this whole thing. No one knew that PopCap was making this game. If you think back to around then, this is a game that’s not — it wasn’t something that you would think PopCap would make. It’s more of a strategy game. It’s more mid-core or hardcore than any other PopCap before it. It has zombies in it. Who would have predicted a PopCap game with zombies in it? It wasn’t their typical fare.

We released the video on April 1 of that year and said nothing more than that. The video itself took off, and people were also speculating about whether it was real. PopCap’s making a zombie game? But the power of that song and the video itself, it piqued a lot of people’s curiosity. That, combined with when the game came out — people just fell in love with it right away. People couldn’t stop playing it. That built on PopCap’s existing fanbase. PopCap was already starting — they had their casual fanbase, but Peggle had also come out and gotten more people in the mainstream game industry to take notice. All those factors combined.

GamesBeat: I thought what was so rare about it was that it had this sense of humor. So few games actually pull off humor so well. Little things like the heads falling off. In hindsight I’m sure humor isn’t easy to pull off.

Fan: [laughs] I always wished for more humor in games in general. Making it, the game just naturally lent itself to that kind of thing. As we realized the silliness of the setup we were using — you can’t play it serious. In what other situation are plants going to shoot pea projectiles at zombies? That’s just ludicrous. You can’t play that straight. You have to go absurd. That lent itself to a lot of random bits of humor here and there. I’m glad you appreciated that. For sure it’s one of the unique elements of Plants vs. Zombies.

GamesBeat: It got so popular that it started becoming more like a cultural phenomenon.

Fan: Another big part of that was — I think our timing was pretty good. We talked about how the game came out on casual game portals and Steam. It was all on PC. When we started making the game, the interesting thing was, the iPhone didn’t even exist yet. Then, midway through, toward the end, we got wind of this really cool Apple phone coming out. Right after Plants vs. Zombies launched and had a lot of buzz around it, a team spun up at PopCap to put the game out on this untreaded new platform, the iPhone.

The iOS version was what really made the game become a cultural phenomenon. Nowadays, looking back, people think of Plants vs. Zombies more as a mobile game than anything else. Another huge factor was the iPad. That was also introduced right around then. In the very beginning, you would go on the iPad store and there’d be just a handful of games, and the only good one was Plants vs. Zombies. That benefited us a lot. You got an iPad and what cool app would you get for your new device? How would you show it off? What was the one thing to buy for your iPad? For a lot of people that was Plants vs. Zombies. A lot of it was the right place and the right time.

Above: George Fan and his buddy.

GamesBeat: Was your presence on the iOS devices a lot bigger than the PC?

Fan: It really was. We got Plants vs. Zombies in front of a lot more people that way. I don’t know what order of magnitude, but you’re definitely adding a zero.

GamesBeat: It was still a paid game, right? It didn’t use the free-to-play model that everyone was starting to talk about.

Fan: Yeah, it started off as a $2.99 game. Again, it was a question of — just the discrepancy of, if we were selling on PopCap’s site for $19.99, and you could get it on Steam for eight bucks, and then now you could get it on your phone for $2.99 — I said, “Okay, is this going to fly?” But the people that were pricing it had obviously thought it through, pricing it based on how other apps were priced. If we sold it for 20 bucks it just wouldn’t have sold.

Back then we also justified it with, well, you don’t get all the features you get on the PC. Initially the iPhone just didn’t have the processing power. We couldn’t do something like challenge mode or survival mode, where there’s hundreds of zombies on your screen at any time. We didn’t put that in the game initially, so that was kind of the justification. You get what you pay for on the PC because we have all these extra modes. But eventually all those made it over anyway. That’s just the result of it being the most popular way to play the game. Why not juice it up?

Above: George Fan

GamesBeat: What were some things that transpired after all this success? How did everything play out for you and for the franchise?

Fan: One of the phone conversations I remember was — pretty quickly, after Plants vs. Zombies had come out and people were realizing that this game was taking off, people at PopCap wanted to make a sequel. They asked me first. “George, we want to make a sequel. We want to know if you want to be in charge, if you want to lead the project.”

I gave them my thoughts, where I was coming from, which was — I’m a creator. That’s what drives me. For a lot of people like me, the reason they would do a sequel is, “I made this game and it’s really good, but I was forced to release it before it was truly polished and there were features I thought of, and I really wanted to add, but I ran out of time.” You see the full potential of what the game could be, but you didn’t get to make it the first time, so the sequel is a chance for you to complete the game you always wanted to make. Or sometimes the game comes out and then you hear people review it, and they love it in a lot of ways, but there’s something missing. “Hey, I’d love to see this in a sequel.” Then you think, “Okay, I want to make that game now.”

In the case of Plants vs. Zombies — you asked me earlier how long it took. It took three and a half years to make, which surprises a lot of people, based on the scope of the game. I think we could have released it a whole year before that. The game was essentially done. It was in a state that I think a lot of people would be proud to release. But we spent a whole year after the game was done polishing it to a sheen. That’s a big part of what ended up making Plants vs. Zombies stand out so much — all these extra modes we added afterward, the extra time we had to play through the campaign and get everything tuned correctly.

Above: George Fan decided on five lanes for Plants vs. Zombies.

I felt like, as a creator, I’d already made the game I wanted to make. There was nothing I wanted to add to it. So when they asked me if I wanted to make a sequel, I really knew it wouldn’t be that fulfilling to me. The drive wasn’t there. Also, I’m a fan of putting myself in the place that’s most needed. For instance, Plants vs. Zombies was a new IP that came out of nowhere, that was born from my brain. I wanted to do what I felt like was going to be best and spin up another new IP. I thought that was the most unique thing I could offer PopCap, and it was also the problem I wanted to solve, the kind of thing I wanted to work on. It wasn’t in so many words, but I said all that to PopCap. So I had the opportunity to work on Plants vs. Zombies 2, but instead I started working on a new game. I wasn’t officially on the Plants vs. Zombies 2 team.

However, I’m still very — I wanted it to succeed because Plants vs. Zombies is obviously very near and dear to me. I did spend a good amount of time early on with that team. I had a lot of phone calls with the team. “This is what makes Plants vs. Zombies what it is. You’re doing a sequel, so here’s what you have to think about. You have a lot of challenges. PopCap is a company that makes stuff accessible to all. You have to maintain that. You need to do a ramp-up all the same, easing people into Plants vs. Zombies 2, but you also have to take into account that a lot of people will come in having played Plants vs. Zombies and learned all this already. How do you cater to both audiences? How do you make sure the people who’ve never played a Plants vs. Zombies game are being handheld correctly, while you’re not boring the people who have played it?” Early on, then, while not being officially part of the team, I did work with them a lot.

GamesBeat: How long did you stay at PopCap?

Fan: I don’t remember exactly. I want to say maybe 2013, maybe four years after. It feels like a long time.

GamesBeat: Is there a brief description of why you left?

Fan: I joined PopCap to make the best games I could. I have a bunch of games I want to make and I want to make them the best I can. I think that while Plants vs. Zombies was being made, PopCap did — props to all of them. Having worked on games before and after that, they facilitated the process of making Plants vs. Zombies, made it so smooth, it was really — I look back and I feel like it was a special time. I felt like that’s what allowed me to do my best work.

As the industry changed, first it was a race to the bottom in the App Store. Like I mentioned, Plants vs. Zombies cost three bucks. Because of the way the App Store was structured, where it’s not about gross price — it doesn’t matter if your three dollar game sells makes three times as much money as a one-dollar game. The one-dollar game is still going to be higher in the charts because it sold strictly more copies. That’s the way the App Store was structured. It was just based on units. You wanted to get to the top of the charts, because you’d get recognized and naturally sell even more. I feel like that’s what caused people to price their games lower and lower.

Above: The zany George Fan

It also changed the appetite among users of the App Store. If everything is 99 cents, then you look at a two-dollar game and think, “That costs way too much. Why bother with that when I have all these great 99-cent games to play?” For some time, 99 cents was the lowest you could pay for a game, until — I don’t know who first said, “What about free? That’s where you can go that’s lower than 99 cents.” And then how do you make money? Make it free, but charge for stuff in the game after the player’s already in.

That’s how the App Store evolved, and PopCap was directly in that segment of the industry. This was all happening. I guess I’ll say that not all of the ways things were evolving led to games being more fun overall. There are some aspects of this business model that make it so — you’re not making games to be fun anymore. You’re playing to — here’s the stuff that addicts players, that makes people come back. You’re implementing these strategies to hook people, but they’re not necessarily having fun with your game anymore. They’re compelled to play because they need to increase their level or feel like they’re making some other kind of progression. But if you asked them, “Hey, take a step back. Strip away all of this. Is the moment to moment gameplay fun for you?” in a lot of cases I bet the answer would be no.

My initial mission in coming to PopCap was to make the best games I could. I wanted to make them as fun as possible. Meanwhile, this divide started forming between me and a lot of the rest of PopCap. “George, you gotta understand, this is where things are trending. This is where the money is being made now. The stuff you value is just becoming a lot less viable in our market.” That rift got big enough that it didn’t make sense for us to work together anymore. That’s the way I see it.

GamesBeat: It was almost more over business model thinking, then, as opposed to things that had to do more directly with game design?

Fan: Yeah, it was really the business model. That’s what caused the rift, I would say.

GamesBeat: We had our GamesBeat conference last week. Some of the guys were talking about going into blockchain games. Their reason for doing so is that it can change the business model. They felt like free-to-play is so broken because it puts the developer at odds with the player.

Fan: That’s a good way to put it.

Above: George Fan (right) shows off Octogeddon to Dean Takahashi

GamesBeat: You have that balancing problem. How does a guy who paid $10,000 square off against somebody who’s paid $5, or never paid anything? How do you balance that game? If free-to-play is broken, in some way it validates your thinking back then.

Fan: I recently thought about this. We were talking about when the App Store first opened. I remember those times. It was pretty awesome, I thought, in that — I would download a bunch of games on my phone. I’d find this cool little tower defense game or something. I’d be playing 10 games at once and they were all unique and interesting.

Now I don’t play all that much on my phone like I used to. In some ways, I’m sad about where the mobile game market has evolved. A lot of the games that are there now just aren’t for me. But I’m hopeful that parts of this trend are reversed, some of the things that are problematic that you mentioned.

Another thing is, the games are designed — a lot of them are presenting you with an obstacle, and either it takes 10 hours for the building to build, or you just can’t build it at all until you pay up in real money. It’s not very satisfying to me to bypass a challenge by paying money. I don’t feel like I accomplished it. I feel like my money accomplished it. I don’t get a sense of achievement.

People complain about grinding in video games sometimes, where you have to farm a level for more cash to save up to buy the sword you always wanted. Yeah, if that’s not balanced correctly, that can be a problem. But I always felt way more satisfaction when I was willingly — when I wanted to spend my time and I had a goal in mind. I want that sword and the only way to get it is to play this level a couple more times to get the cash for it. That always felt more satisfying to me than just spending $5 out of my wallet to get it instantly.

Also, I feel like in the first case, the game designer balances the game so that it’s about the right pace. It’s not overly tedious to get that sword. You have to maybe replay a level a couple of times, but there’s still enough interesting things happening at that point that it doesn’t feel like a complete grind. Whereas I feel like the way things are balanced in some free-to-play games is they want it to be extremely tedious. “Yeah, you can do this level 100 times to get the sword, or you can pay the $5 and get it now.” They have to make it an obstacle. I feel like that throws things out of balance for the people who don’t want to pay. It makes for a way more tedious experience.

GamesBeat: How did you apply some of the lessons you learned to Octogeddon?

Fan: Whenever I sit down to make a game, I always make sure it’s a game I want to play. What kind of game is Octogeddon? It’s not going to be a game where things are artificially inflated to be more tedious. I never thought of Octogeddon’s business model to be anything but just paying up front to get everything. Once you’ve done that you don’t have to think about your wallet anymore. You just enjoy the experience the game designer has brought to you. Never at any point do you have to re-evaluate whether you want to spend any money to bypass any of the game. It’s the classic game experience I’ve enjoyed in the past. I wanted to bring that part of it to people who are looking for that kind of experience.

Above: Octogeddon debuts on Steam on February 8.

GamesBeat: How did the game turn out, from your perspective? I don’t think we ever caught up on the post-mortem.

Fan: I don’t know if you’ve heard, but it’s coming out on Nintendo Switch in a couple of weeks. That’s super cool. That’ll be a tremendous platform for it. I’m extremely proud of the game and how it turned out. There’s so much charm to it. On the one hand, it’s hard to describe. It was hard to pitch the game, because it’s unlike any game before it. I’ve never played a game where you’re a Swiss army octopus and your controls are basically spinning your many limbs, each of which does something different. That experience is very unique. I haven’t seen anything like it. On all those fronts I’m proud of what we did. I’m very hopeful that the game does well on the Switch. It’s a prime platform for it.

GamesBeat: Was there any feeling that you had hoped it might be the same kind of cultural phenomenon again?

Fan: That’s a problem I’ve been facing as a developer. I’ve heard war stories from other developers — making their magnum opus, making something where you can’t dream of it becoming that much of a phenomenon. I had that with Plants vs. Zombies. When that happens, how does that affect you afterward? I don’t think it would have been healthy for me to say, “I made Plants vs. Zombies. Look at how many people it impacted. Look at the reach it had. Look at how much of an insanely polished game it was, how many people loved it. Now I want to try to top that.”

I don’t think that’s realistic. It can actually do a lot of harm to think that way. But it’s tricky, because as a creator that’s all you want to do. You don’t want to be complacent and say, “I did it, and now I’m never going to do anything that remotely compares.” But if I did everything from now on with the goal of topping Plants vs. Zombies, that’s too much pressure.

I feel like creativity flows best when there’s the right amount of pressure. There’s the Goldilocks zone of pressure. Too much of it and you have no room to be truly creative, because there are all these constraints. It has to sell this much, do this well. You’re not free to have this wild idea over here. It’s not scientifically proven to make this much money or reach this many people, but it sounds cool, and it could be really fun. If you’re in that mindset I talked about, you’d cast those ideas aside. You don’t follow these paths of, “What if I did this interesting weird new thing?”

Above: Octogeddon adds more arms and weapons over time.

GamesBeat: You chose the harder road, which was to not do a sequel, to do something original, and to try to do something that was of good impact. You didn’t want to just do a small game after you did such a big game. You wanted to move higher.

Fan: I feel like I have a lot more to say. The best use of my time is less — someone else could take the helm of Plants vs. Zombies and theoretically do a good job of continuing that series, being a steward of that series. I just felt like my time would be — one of the things that I excel at is coming up with new mechanics and new kinds of gameplay. I felt like if I didn’t do that, there’s more of a void out there. If I wasn’t me, I would want me to do that. [laughs] I love playing new games, new game concepts. That was just better servicing the world, if that was the path I took.

We were also talking about what it feels like to be in the shadow of Plants vs. Zombies. Having created something like that, that much of an achievement, creatively speaking — in a lot of ways I’m done. I don’t really need to — I don’t predict that I’m ever going to top that. Not every creator is even given the chance to do something of that magnitude.

GamesBeat: How do you go on, but also try not to put that pressure on yourself? There’s probably some advice for developers there about how to mentally deal with this challenge.

Fan: I’d say that I try to trick my own mind. [laughs] It’s tough. Your mind is smart about it. There are ultimately things you can’t change your viewpoint on, but if you have a goal of where you want your mind to be, that definitely helps. Being aware of it. It can actively damage things to think in the form of, I have to always top my previous accomplishment. That’s great motivation while you’re starting out and building up. Every game you make is better than the last one. But after you’ve done something on the scale of Plants vs. Zombies, I don’t think it’s productive to think that way.

At the same time, because you’ve been motivated by that for so long, it’s almost like an instinctual creative need. You just have to keep actively telling yourself, “That’s not healthy.” Your goal now should be — you still have things you want to make. You want those things to be as good as possible. But it’s not healthy to think of them in terms of, you have to top something as colossal as Plants vs. Zombies. You just can’t think that way. It puts the wrong kind of pressure on you. You feel confined. You have to do everything almost too scientifically, too by the book. You’re not free to explore some of these wilder ideas you might have.

It’s also sort of like setting — I know I can’t quite change exactly what I’m thinking, but here’s where I want my mental state to be. Recognizing what might not be healthy for you, so you spend less of your time thinking in those terms. There’s going to be some instinctual need to feel that, because that’s just what a lot of the drive for coming up with this stuff in the first place is about. You want to improve. You want to get better. But nowadays I think of new games as — here’s a project on its own. I’m not trying to think of it in the scope of what I’ve done before. I’m just tackling it in isolation, sort of. I want to make this the best product I can without the pressure of having to top my previous thing.

Above: A sunflower is born.

GamesBeat: You’ve also gone back to work at a bigger place. How is that for you?

Fan: It’s been so excellent. It’s a unique situation for me. My mindset is just more — I work better in small teams. I have more of an indie mindset. That’s just where I thrive. Working at a bigger corporation is definitely more of an anomaly for me these days. However, I’m also the biggest fanboy for Magic. That’s where I work at these days, at Wizards of the Coast.

It happened there was an opportunity for me to move up here for — it was supposed to be six months, working on Magic for a bit. I keep talking about how I need to put myself where I think I can contribute my strengths the most. I don’t think that’s where I should put myself long term, working on a game that already has a ton of designers that are great at what they do and have made the game what it is, made the game awesome. I don’t think I’m contributing to the whole gaming landscape as much as I could be if I stay here long term. However, it’s just something I couldn’t pass up doing. In some ways it’s a dream of mine to work with Wizards. I’m getting that out of my system. It’s been a blast.

This gig has caused me to do something very unusual for me. I’ve spent my whole life in the bay area and never really left. It was a pretty big deal for me to do this, my first time spending time living outside the bay area. But I don’t regret it at all. They’ve been treating me awesome there. I just really enjoy going in to work and getting to work on Magic, this game I love and I want to see improve. I realize my time here is limited, so I’m trying to seek out areas where I can help improve the game as much as I can while I’m here.

GamesBeat: As far as Plants vs. Zombies goes, EA has continued on with new games. Do you have any observations about what you’ve seen from them, or anything about where you might hope Plants vs. Zombies can still go?

Fan: I can tell you about something that I would personally like to see, which is — this is a phenomenon I’ve noticed. Obviously I make games I want to play. For instance, I made Insaniquarium way back when, and the same thing happened with Plants vs. Zombies. I finished those games and thought, “This is a really cool game. I’d love to play it someday.” As a player, you know? There are certain things that you can’t really get, because they’re not going to be a surprise. You’re not going to be thrilled by new things as they happen. You’re the creator of it, so you know exactly what new plants you’re going to get, what new zombies you’re going to encounter. The thrill of that discovery isn’t there.

I keep thinking it would be great to do this at some point, but by the time — it’s rare for me to go back and play any of these games. I’ve spent hundreds of hours already playing them, to the point where I don’t necessarily want to — it’s either replay a game I’ve already spent 100 hours playing, and meanwhile I could be spending that time doing one of the many awesome new game experiences out there. I just tend to opt for that rather than go back and play something — I’m not going to be very surprised or delighted by the new plants I’m getting in a game I made, anything like that.

Above: Zombie

At the same time, I made the gameplay in Plants vs. Zombies like that for a reason. I would love to play someone else’s take on it. I would love to clone me, have myself make Plants vs. Zombies, not know any of the surprises that are in store for me, and play a game exactly like that. That would be amazing. I guess I’m saying that I’d love to play — I doubt this is going to happen, but I’d love to play a theoretical Plants vs. Zombies 3 that doesn’t ask me for money in the middle of it. It’s just a good old-fashioned great time. I can buy the game and get engrossed in this world and be delighted by these new plants I’m encountering and plan out my strategy against the new zombies I’m facing, not knowing what’s about to happen next because I actually made it. That would be something I’d personally love to see.

As far as the bigger scope of things, it’s pretty awesome that Plants vs. Zombies has branched out into other genres. That’s really neat. It’s bringing with it the same aesthetics and fundamental design values. One thing I realized is — Garden Warfare, I haven’t played that a lot, because I’ve never been big into first-person shooters, but one of the cool things about it is, say you’re a parent. You have a young kid and you don’t want them playing shooters because they’re all hyper-violent. For a while that was all there was. If you wanted to play a first-person shooter, you had to play something that’s pretty full of violence.

One of the really cool things about Garden Warfare was that now you have an option for your kids. If they’re interested in playing first-person shooters and you want something a bit more family-friendly, Garden Warfare is there for you. I thought that was awesome.

It’s been cool to see — when conceiving of Plants vs. Zombies I never imagined it to be anything more than the tower defense genre, partially because of what we talked before. Plants are really suited to being towers and zombies are really suited to being the bad guy when you’re trying to keep the gameplay on one screen. It’s such a great fit for that, but I didn’t know if it would be necessarily a great fit elsewhere. I didn’t imagine something like Garden Warfare because from what I know about plants, they don’t move. So how do you make a first-person shooter where you can’t move? They solved that by just making the plants walk on their leaves as if they’re legs. [laughs]

GamesBeat: Was there anything else you wanted to say?

Fan: I think we covered everything. Or we covered a good amount of stuff.

GamesBeat: You could say, grab Octogeddon on the Switch.

Fan: [laughs] Coming soon to a Switch near you, Octogeddon! Be a giant mutant octopus and destroy the world to your heart’s content, in your own living room or on the plane, wherever you decide to take the Switch.