Hand: Just to jump in a bit on the valuation and the infrastructure side, when I see the stat about this being a billion-dollar industry, not only does that show that the potential huge upside of the esports category, but it’s also really focused on the professional level. That’s like quantifying what baseball is worth locally and only talking about the value of the major leagues. To me, there’s a huge amount of growth and opportunity that isn’t being captured right now in those estimates.

As far as the investment side, what’s been fascinating for us as more of a mainstream esports play is the way we’ve attracted some non-traditional investors. For example, companies like Nickelodeon have invested in us, because we’re running youth leagues. Cinemark has invested in us because theaters are empty a lot. A movie theater makes for a pretty decent playing field for esports at an amateur level. It’s been interesting to see, to your point, that the numbers don’t lie. It’s attracting a lot of interesting attention.

To me, being at this for three years, I think this year is the year of infrastructure. This is the year that, through the work Overwatch has done with their league, and the same with League of Legends, through the venues’ role in this and the localization of esports — this seems to be the year where the focus is on making sure we have sustainable leagues and sustainable venues and locations to dig in and put down the stakes.

Cohen: One more quick observation, and it plays to the historical stereotypes of who would want to watch this. I think there are a lot of people in a certain generation, and I’ll pull myself into this category—their rudimentary understanding of the esports audience is it’s a 15- or 16-year-old acne-faced boy in a basement with a screen just playing. Nothing is further from the truth. It is intensely community-based. That’s an incredible opportunity on so many levels, not only commercial but otherwise.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

People want to be together. They want to be together to play. They want to be together to watch and participate. That creates, for us, from an experiential basis with our venues, huge opportunities to deploy in totally different ways, different from some conventional sports. That’s another old tale that needs to be dispensed with in terms of what we’re dealing with today.

Hand: Absolutely. Super League has run about 2,000 events over the last couple of years. If I have any regrets, it’s the way that I spoke about our target demographic in the early days, because there was a subtext, or an apologetic tone to it. “Isn’t it great that we’re getting kids together?” Almost implying that they were a niche group that was disconnected and alone.

Having run that many events — and we also run adult events, 16 and over events — we got it all wrong. This is such a diverse psychographic of people. We have girls who game. This should be a gender-neutral sport. Gamers have higher graduation rates and household incomes than traditional sports fans. This is a very multifaceted, accomplished group.

The other big headline is that gaming is no longer something you grow out of. It’s a lifestyle decision. People will come in and out of different game titles. Sometimes they’re players and sometimes they’re spectators. But it’s time for us to debunk this idea we have about who a gamer is.

Wakeford: About spectators and viewership, a fun fact. Nate has done an amazing job as the commissioner of the Overwatch League, as you can see up here. Viewership for Overwatch League on Thursday nights surpasses that of the NBA on Thursday nights. Think about that for a second. We’re talking about a massive audience. Second, back into investment and capital—investment into esports in 2017 grew 1,125 percent year over year. A massive inflow of capital, and that’s just on the venture side.

GamesBeat: It felt like I wrote an esports story twice a week, usually about an investment.

Wakeford: The other areas of investment that don’t get reported as much, although they’re often buried in the headlines — it’s the investment from traditional sports moving into esports. It’s a tectonic shift that’s happening in the traditional sports industry. If you look at the viewership numbers for a number of traditional sports, they’re going down.

Nanzer: Especially with viewers under 35.

Wakeford: With the millennial group, there are more millennials watching esports than a number of traditional sports out there.

GamesBeat: We should mention some of these names. The Philadelphia 76ers have invested. Robert Kraft has invested.

Wakeford: Within the Overwatch League you have the Kraft family, the owners of the Patriots; the Kroenkes, the owners of the L.A. Rams; Fred Wilpon, owner of the New York Mets. That’s not to mention NBA2K, which now has about every NBA team adding an esports component to their organization. This is a major shift in terms of what we’ve thought about as traditional sports. It’s a change in the landscape, a paradigm shift that’s fueling this investment. It’s why you’re all here today, because it’s a radical shift in a massive industry, in the traditional sports industry.

Nanzer: We’re seeing the way fandom plays out, and it’s exactly the way you’d expect it to play out in traditional sports. We had this moment two weeks ago at the Blizzard Arena, where I feel like I saw that local esports is born. It was Steve’s team, the Valiant, playing Stan Kroenke’s team, the Gladiators. Just organically, half of the audience was purple and half of the audience was green. They’d self-selected which side of the arena they’d sit on. They were talking back and forth. It was amazing to see.

We’ve already seen viewing parties all across the country. The New York Excelsior, Wilpon’s team, already has a supporters club that came together organically and goes to a bar in Brooklyn for every single game to watch the matches. We’re really seeing the fandom manifesting in the same way it manifests in traditional sports. We’re hearing from young fans — who spend all their time watching other people play games on platforms like Twitch and YouTube, and are disengaging with traditional sports — that this is finally the New York or Los Angeles team for them.

Cohen: I would point out that while it is a radical movement in some ways, it’s not in others. Our Los Angeles Kings players, Galaxy players, Lakers players, they’re avid fans of esports. Zlatan Ibrahimovic has a Valiant jersey, I’ll tell you that right now. That’s important, because in these legacy sports — which have their own authentic credibility with their fanbase — the players within these sports themselves have incredible credibility. They’re competitors. They work hard. They’re elite at what they do. When they like something, their fanbase associates with it.

Part of what we’re creating here, and what the Overwatch League is an example of, is a different kind of credibility and authenticity. Then you’re not a Trojan horse anymore. You’re part of the family, and when you’re part of the family you can introduce yourself in all sorts of ways and have different dialogues with your fanbase than you can if you’re just a commoditized product.

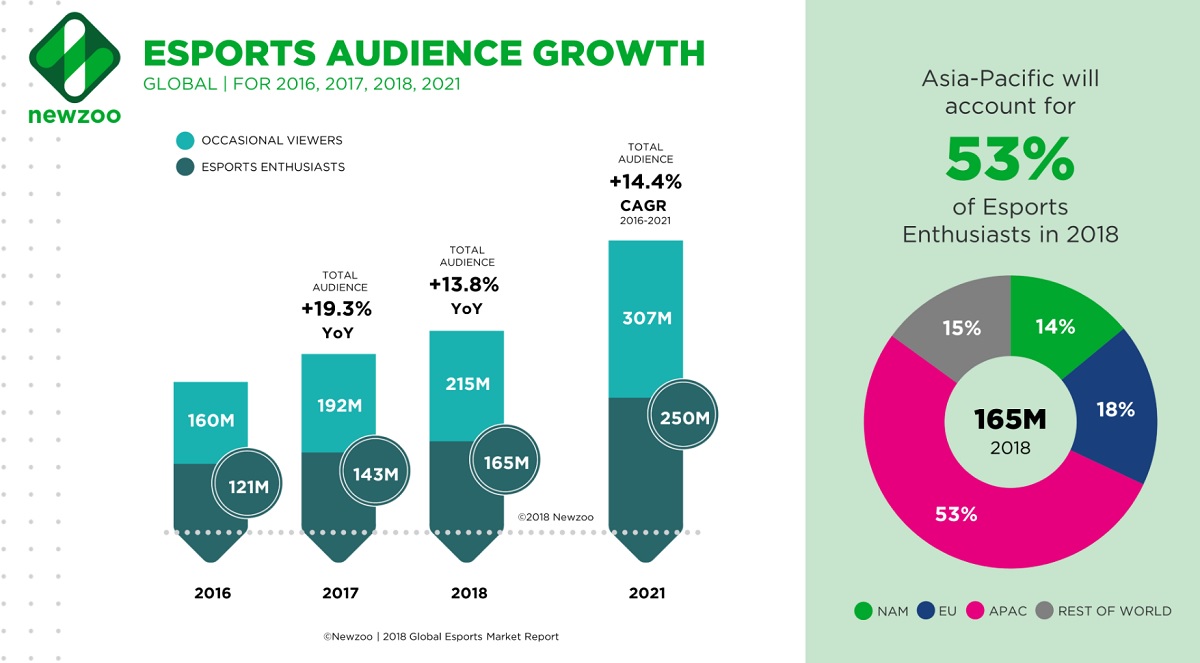

Above: Newzoo expects the total esports audience to grow to 557 million in 2021.

GamesBeat: Yesterday Steve Ballmer was sitting in this slot. In 2014 he bought the L.A. Clippers for $2 billion. We’ve done a good job getting people excited about the opportunity here, but we should flip the coin and talk about some of the challenges as well. One of them is — Dennis Fong, who was at our GamesBeat conference earlier this year, was one of the first star competitive gamers. He won John Carmack’s Ferrari as the world’s best Quake player 20 years ago. He said that nobody is making money in esports. That’s a little detail we may have left out so far.

Comparisons to traditional sports happen a lot. Newzoo points out that the average esports fan right now spends about $4.58. The NBA basketball fan spends at least three times more. These raw numbers may not sound right, but ratio is correct. In a given year NBA fans are going to spend a lot more money on their fandom. They’re more passionate, at least, about tying their wallet to what they’re interested in, compared to esports fans. That’s part of the challenge for esports.

What has to happen? What parts of the business model still have to mature?

Cohen: Just a couple of quick comments. First of all, I don’t think that statement is generally right. From an event-based perspective, I can tell you that plenty of folks in the ecosystem are making money. When you sell out three days at a stadium for a final, lots of people are making money.

When you start talking about leagues and about ARPPU — yes, on ARPPU there’s room for improvement. But this is all new. The leagues are new. Right now the critical thing is building the proper infrastructure from the ground up to make sure this is sustainable for the long term. You’ll have to make some investment on the front end to allow that system to prevail and thrive in the long term. If there’s an expectation that you’ll be making big money in a new league on day one, then you have your own problems. You’re in the wrong place for your investment.

Hermann: To add to that, I’d like to zoom out one or two steps, because typically what happens when you talk about esports is you focus on the top-tier competition, the tier-one leagues that are currently active. But for any ecosystem to thrive and be sustainable, you have to look at what happens beneath those top levels. These are some of the things Ann touched on earlier. What does a little league look like? How do people grow into that space? Where do future athletes come from? How do they start acquiring their specific preferences? How do we grow fandom?

One of the areas I was pleased to work on while I was at Riot Games was the collegiate space. College is such a great blueprint for how sports can work, especially in the U.S. ecosystem. You already have all these different things in place. Esports fits into that narrative perfectly. Riot built out a club program that built out to something like 800 college clubs. I believe Blizzard has a similar program in place running leagues in that space. Scholarships are paid out to students. But more interestingly, colleges are starting to set up scholarships on their own to attract students to join their competitive teams and participate in those leagues.

One of the most exciting projects for me to work on was getting the Big Ten conference on board to run the full season for 12 of their 14 member schools and have them compete. It was an interesting experience, flying out to Chicago to talk to the commissioners of their sports groups and getting them to understand what’s happening on their campuses, what students are doing these days.

If it wasn’t for the fact that I’m working in the space, I’d probably have 15- and 16-year-olds calling me out about everything I’m not doing right and not understanding. I would have a huge disconnect with that space. But it became apparent when I was talking to some of the existing people who work in traditional sports, the last time they played a computer game might have been the ‘80s, in the heyday of Pac-Man or something. There’s a lot of education that still needs to happen to go there.

GamesBeat: One very interesting fact for the parents in the room is that Riot is sending 500 students to college on League of Legends scholarships right now. What does that do to your advice for your kids about whether to study or play video games?

Hand: There’s something about League of Legends as a game, and Overwatch has a lot of these attributes as well. There are deep layers of strategy and critical thinking. It’s not just that these esports scholarships necessarily mean those people are going to become professional players. But it says an awful lot about that person’s cognitive potential and a whole range of career options that are available. It’s quite a good metric for the brainpower of that individual.

Nanzer: We have a group we work with at Blizzard called Tespa. It’s our collegiate esports. Across all the chapters — I think we have 400 or so chapters across the country — almost two-thirds of the people that participate are STEM majors.

Hand: One of the more popular conversations we’ve been having with both publishers and professional teams, which are really our two most important stakeholders as the amateur league system underneath — there’s a very popular conversation about the under-18 market. In addition to our youth leagues, we’re starting to run high school league competitions as well. That matters to the pro teams, because finding you around 16-18 is important to them.

Of course Tom Brady is a quarterback at 40, and the life of a professional esports athlete will extend as well, but right now it tends to be that the heart of their career is in the 20-24 range. Also, as I alluded to earlier, the kid who plays little league is going to be a baseball fan for life. The importance of introducing the future esports fan is important as well.

When you get to the game publishers–once you join a league you participate in a sport in a different way. I always jokingly say that I played tennis growing up, and I could have learned to play hitting a ball against the garage door, but something different happened when I joined a team, the stickiness I built around that sport. There’s also character-building and teamwork and all those other good attributes. When you’re trying to get people to introduce each other to game titles and to esports and get them to stay with that sport for a long time, sometimes being part of a league and a team is a good way to do that.

Above: Ramon Hermann (left) of Tencent America and Nate Nanzer of Overwatch League.

Wakeford: We’re seeing the evolution of—there’s now esports organizations across high school. There’s collegiate esports. And at the professional level, the professionalism and the compensation have become very real. Nate, you’ve done a good job with the Overwatch League setting minimum requirements. We have salaries that are in the hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars for esports players. Health benefits, 401k, all the types of benefits you’d associate with professional players.

Just to put this in perspective, within the leagues we play in, there’s a player we compete against, Faker, and he’s reportedly making more than $5 million a year. This is not just kids in basements playing. There are real career paths. And this is just the start.

Nanzer: Part of it is, in addition to the incredible focus and cognitive ability you have to have to play these games — we had a video running over there, one of the matches, and there’s a player named Birdring. I promise you, not a single person in this room is physically capable of doing what he does. You could spend the next year doing nothing but playing Overwatch and you would still—he could close his eyes and destroy you. The reaction time, the ability to move a cursor a precise point in fractions of a second — there’s a physical component to this, and these players work incredibly hard. They spend a lot of time practicing.

But I think one of the other things that speaks to the professionalization of esports—in the Overwatch League we have multiple teams that don’t just have coaches. They have performance coaches. They have chefs. They have nutritionists. They have team psychologists that work with the players. There’s a ton of infrastructure around the pro players to help them succeed. The teams in esports that are the most successful are the teams that invest in the resources around the players and treat them like the professional athletes that they are.