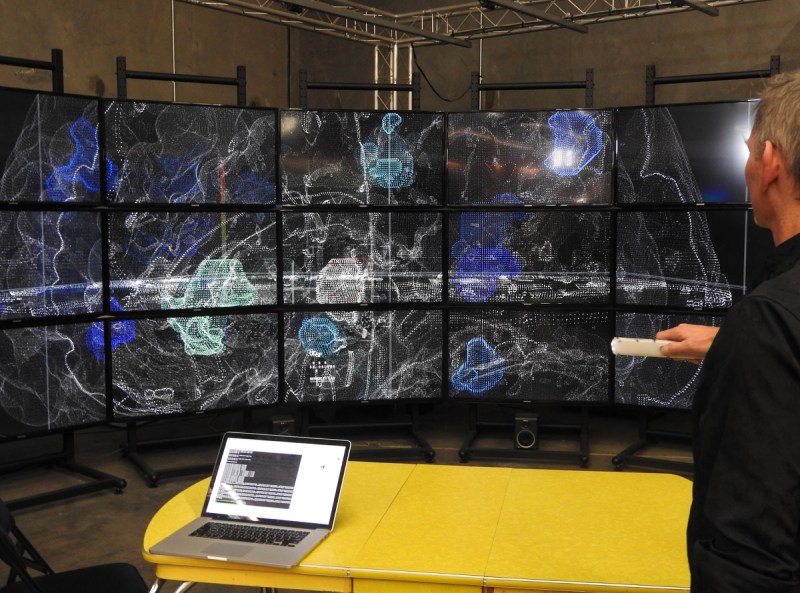

Above: IBM created Watson Experience Centers to help humans grasp complex ideas.

VentureBeat: Is there any kind of explanation you’d give about the ROI on this? Why would somebody want to spend a lot of money to set up a center like IBM has done? How would you describe the advantage or the return?

Hawkes: The return on investment — again, I’m speaking from a design standpoint. When I work with designers in the space, or people that have worked with traditional modes, often there’s a moment where their brains kind of crack open and they start seeing things differently. A lot of that has to do with three fundamental concepts that underlie G-Speak, the platform we use to drive all of this.

First is that computing systems should be inherently multi-user. Everything we use, all the fanciest bits that we have from Apple and Microsoft and the rest, they’re primarily single-user interfaces. They might be connected through the cloud, but they don’t function the same way we do when we’re sitting around a tabletop working on a hard problem on a whiteboard together. Creating systems that are on equal footing with that cognitive space is very important to us. As a part of that, making sure that the space itself is spatial — the screens aren’t just on the walls, but they’re on the walls for a reason. They physically behave like they would in a real space.

And then the last part is just connecting multiple hardware devices into a unified interface. We have Macs. We have phones. We have Windows machines. They all do different things well for different reasons. But if they’re connected together, networked in a meaningful way — not just a cloud-based way or a file-sharing way or chatting with one another, but networked in a way that they can unify to create something bigger — that becomes extremely exciting. The ROI is more around changing hearts and minds, I think, in some cases.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

We’re excited because the cost per pixel continues to plummet. As you walk around now, even your corner bodega probably has a large display screen with prices in it. Fast food restaurants and the rest — more and more of our architecture is becoming display surface. This is a concept that we’ve understood for a while now. But what we don’t know is what to do with those pixels once they’re there. Is it just a billboard? Could it be active space?

Above: Oblong’s prototype for an immersion room in May 2017.

Similarly, in the VR and AR space, there’s a lot of excitement there, but the content — now that folks have the heavy hardware, they’re scrambling to generate good content. We have really strong shops sprouting up all over Los Angeles creating cinematic experiences, art-based experiences. We have some industry-based companies as well. But what they’re really struggling with is the interface. How do humans actually interact? What are the implications, from a UX standpoint, of trust? I have to blind myself to the real world in order to get this magical virtual world.

Standing in an immersive space like IBM’s space, we can have a group of 12, 15, 20 people having a shared digital experience with the same level of immersion, without losing context in the real world. We feel there’s a lot of power in that. These aren’t new concepts. They’ve been kicking around. Years ago UC Santa Barbara developed the AlloSphere, the near-spherical sound and digital display surface, to explore similar concepts. Others have existed in Chicago and San Diego for data visualization.

IBM is pushing these to be active interfaces. I think originally they spec’d out the space for its cinematic appeal. They wanted it to be more like a fancy theater of sorts. I don’t think they expected it to become the live interface it has become.

VentureBeat: How long would you say it’s taken to get to this point, at least with IBM?

Hawkes: Astor Place launched in 2014, so it’s been four years now. They started changing their approach to things a couple of years into the original exchange, when they started asking us the right questions instead of just dictating content.

They’ve needed to open space up and make it a little less special. It’s been exciting to see that this year, both in the ability to document it and submit it for awards, but also — Austin Design Week was the second design panel we’ve held in the space. They had another one earlier in the year, in August, at Astor Place, where they invited designers to both see the space and participate in a panel discussion on how we create content for the space. They let us write a blog post about it, which was great. [laughs]

Above: John Underkoffler shows off an immersion room display in May 2017.

VentureBeat: I made a visit to Lightfield Labs in San Jose. They’re doing large-scale holograms, which should be interesting sometime soon.

Hawkes: I look forward to seeing that. We have a relationship with Looking Glass, and recently set up a demonstration where we integrate their display with our wands at the warehouse. Looking Glass creates a live digital lenticular display, so without any — they’re pushing toward the idea of an actual hologram, but the fact that you can look around a three-dimensional object without any special glasses or anything else and share that experience with other people is very exciting.

One last remark. I don’t think you have to have 93 million pixels to get the type of experience that IBM is getting. All of the tools we’ve built to drive those much larger spaces I think have just as much utility in a small office or living room space. We have been talking with various hardware companies. As embedded hardware moves into the screens we watch TV on, they suddenly become a lot more active. There’s a lot of new potential there. We want to be ready with the right approach to interface and tools, so that we can drive that potential.