Yager Development has a rich history of making high-quality games, from Spec Ops: The Line to Dreadnought. And now it has launched The Cycle in early access on Windows PC.

The Cycle is a competitive quest shooter, where you can compete against other Prospectors on the planet of Fortuna III, or you can collaborate with other human players to claim as many resources as possible.

But the planet itself is hostile, and so you have to engage in PvEvP, or player versus the environment versus player. Your rivals are untrustworthy, and you have to deal with The Cycle, a planetary metamorphosis.

I talked to Timo Ullmann, managing director of Berlin-based Yager, at the Devcom game event in Cologne, Germany last week. Yager has always been very ambitious, and The Cycle was born during an internal pitching jam session. Development started at the beginning of 2018.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

The company named it a “competitive quester” because you go through an open world trying to fulfill quests, even as you engage in first-person shooter combat.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Timo Ullmann is managing director of Yager Development in Berlin.

GamesBeat: Tell me about your newest game.

Timo Ullman: The Cycle is the game that we’ve been working on since February of last year. We’ve made a lot of progress quite fast. It used to be an alpha. We got it on the Epic Games Store. It is now in early access. It’s a PvEvP game, meaning that it gives players the opportunity to engage with one another in different ways — antagonistic or co-op mode. Or you could just do quests and engage with contracts that we give you against the wildlife. It’s really about the next step for us, giving people more options, more choices to engage with one another.

GamesBeat: What’s the backstory and the style of the game?

Ullman: It’s set in a science fiction universe. That’s a deliberate choice, so we can have more options. We don’t want to be bound by reality. The universe is already kind of explored, the center of it, and the outer reaches are up for grabs. You take on the role of a prospector, and you can choose to do contracts or quests for certain parties or factions as we call them. Some of them might be state-run corporations. Some of them might be cults. There’s a lot of variety to that. They’ll put contracts out that you can deliver.

It’s a match-based game. Each match is 20 minutes with 20 players. What we feel is interesting is that people have a lot of options and choices in the way they go about playing in a match.

GamesBeat: Is it something like battle royale, or is it very different?

Ullman: When we started, we said that it’s absolutely not battle royale. We’re going beyond that. Watching how people play the game–those who come from other battle royale games, they really embrace the PvP aspect. We don’t want to forbid that. That’s why we say “PvEvP royale.”

GamesBeat: So you can choose to do things that help other players, or just choose to do things that help you survive?

Ullman: By design, you don’t need to kill anyone or be the last man standing to survive. You can win a match without shooting any other players. You just have to fulfill contracts. But there are also players who really enjoy and embrace the PvP interaction, the antagonism. You can do that as well. We’re trying to give people the opportunity to play in their own style.

Above: The Cycle is a competitive match-based quester.

GamesBeat: What other games were already in the market when you started?

Ullman: PUBG was there. Fortnite was there. But when we came up with the concept, we could never have imagined what kind of hit PUBG was going to be. Then Fortnite came around and was an even bigger hit. That’s why, as I say, we don’t want to be mistaken for a battle royale. We don’t want to be run over by these behemoths. The way we see it now, we’re giving you the option to play in different ways.

We felt that battle royale, if you want to use that framing — games like H1Z1 and the DayZ mods — when something is successful in this industry, it always gets copied. We anticipated that there would be a wave of very similar games getting crammed in this market space. We didn’t want to be drowned in that. We wanted to have something that would set us apart from that. We played around with the concept a lot as we developed the game.

It’s our 20th anniversary this year. We had a big celebration in the summertime. During that 20 years, we’ve developed a lot. Nowadays we’re a Yager 2.0, if you will. For the first time in 20 years we’re not only developing the game, but we’re also funding it. We’re the ones commercially exploiting it. We’re marketing the title ourselves. That’s a huge step. We feel that’s long overdue, but now we’re in a position to do it.

GamesBeat: Were there some lessons from previous games that you applied here? Did you feel like you needed more independence to make this game?

Ullman: I think so. We’ve learned a lot of lessons. What we learned on Spec Ops — the strength of narration, the environmental storytelling, that’s something that found its way into The Cycle. On Dreadnought, that was the first time we explored free-to-play as a business model. But we’ve also seen that in order to be agile, it’s more beneficial if all the decision-making is happening in one space. We had overcome some of that friction. We felt that running this game by ourselves, not working with a partner, was something that would help us be more agile. That was a driver behind our decision to self-publish.

I feel like a lot of studios are doing that right now. Given the opportunities you have with so many different platforms, that’s liberating development studios to create and market their own games. They can get out of that dependency, that vicious cycle you used to see. Every time you finished a new game, you needed to find a new gig or go under. Now we’re in a much more comfortable position, and that allows more creativity in the studio. We can come up with some really cool new concepts.

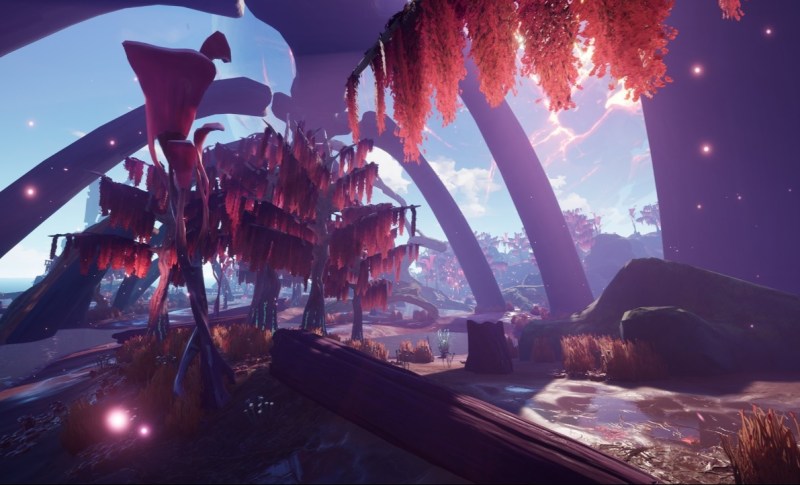

Above: In Yager’s The Cycle, you compete with Prospectors.

GamesBeat: What have you learned from your playtesting so far?

Ullman: It’s really interesting. In the beginning, we thought we might want to tone down the PvP aspect of it. From what we’re seeing, though, there are so many different types of players. It’s quite a challenge because we’re bringing two breeds of player that usually don’t mix. PvP guys are very antagonistic, very competitive, and the PvE players are less interested in taking on other players. They want to engage with the AI. Mixing those two together, you might end up falling between two stools, right? We might not satisfy either group.

From what we’re seeing, though, we’re getting very useful feedback on how to balance the game and how to make sure we onboard people in the right way. We’re not nearly done with it as far as how to draw people into the game, because there’s a balance between teaching the players and letting them explore for themselves.

As I say, if you come from battle royale and other PvP shooters, you just shoot everything that moves. Pretty soon you realize you don’t need to do that, though. The game doesn’t incentivize you. You don’t get any extra points for killing people. Killing them might prevent them from succeeding, from getting first place, so you might still have an influence on who wins, but it’s not a direct relationship.

GamesBeat: How many people do you have working for you now?

Ullman: About 100. We’re growing right now because The Cycle needs more people. We’ve also started to work on another unannounced project.

GamesBeat: I remember the conversation we had about how you had these ups and downs. You almost went out of business. What do you think has helped you survive?

Ullman: Luck definitely played a role. We had kind of retrospective this year, looking back on the past 20 years. I think it’s also attention to detail and loving what you do. As a third party, an independent developer, you always need to be on your toes. You need a good sense of what’s going on in the market in order to not become obsolete. That’s a skill, if I may say so. But luck played a role as well, and having the right people. We have such a cool team. It’s a very diverse team, a very international team. That defines Yager’s games as well. We’re based in Germany, but we have people from various backgrounds.

GamesBeat: If there’s something like a Yager brand, what do you think it means to people? What kind of game can they expect from you?

Ullman: Definitely action-themed, with a strong narrative in some way or another. Our first game was a Wing Commander kind of flight action game. We were trying to tell a story there. Spec Ops was all about the narrative experience. Dreadnought, we were creating a universe, and with The Cycle we’re doubling down on coming up with an interesting universe and giving people different choices in how they engage with it.

Above: Yager’s The Cycle

GamesBeat: Spec Ops: The Line had a kind of morality tale to it. Do you want to continue that in some way in your new games, or is that not necessarily the kind of thing you’re making in the future?

Ullman: No, it’s definitely — it’s not a one to one relationship, but we’re taking what we learned there and it’s transforming into The Cycle. As I said, watching what happens when two players meet each other — are they going head to head, or are they going to work together? It’s creating a game and an environment that allows for multiple approaches. We’re not necessarily making a comment on how that’s going to go, but we’re curious. It’s so interesting to see new people join the game and find out how they’re going to play. That’s a big part of it.

GamesBeat: How do you see yourselves as a developer now? Would you call yourselves double-A?

Ullman: In the beginning — coming out of Spec Ops, we thought we could define ourselves as triple-A because of what we liked about triple-A. Having big budgets, working on a story with a lot of attention to detail and high production values. That’s still the case, especially the attention to detail and to quality. But we want to control our own fate. I wouldn’t call it triple-A anymore because we don’t do crunch. We’re enjoying our new freedom.

At the same time, that comes with responsibility. There’s nobody to point a finger at. If we screw up, we screw up. But we’re also quite agile and able to improve ourselves. The Cycle has come so quickly in terms of production compared to Spec Ops. That was a five-year experience. Even Yager, our first game, was three and a half years. Now, only one and a half years after started production on The Cycle, we’re going into early access.

Over those 20 years of experience, we really took note and took care when it comes to how we can be quicker. In triple-A, in the old days, you’d be working and polishing down to the very last detail. In our new approach, we’re doing things so that people can get the idea — there’s something to take away, to hold on to — but then we put it out and see if it’s working or not. Then we can iterate on it and polish more. It’s quite a different approach compared to what we did on Spec Ops, for instance.

What did you think of the panel?

Above: Yager’s The Cycle takes place on Fortuna III.

GamesBeat: It was a good one. We had a lot more open discussion, I think, because we had the right people. We didn’t have too much corporate stuff. It would have been a very different panel with [big companies] on it.

Ullman: For sure. I think it’s super interesting to talk about responsibility because I would agree. We would never put something out that we felt bad about. But at the same time, we need to be careful as an industry not to define what the standard is. If something goes away because of that, we should call it out. We should have the means to allow for different content to be created. But then again it comes down to, what are the consequences of that? I find that super fascinating.

I feel like there’s no final answer. The notion of making the world a better place — what is that better place going to look like? Who’s going to define that? In the abstract, absolutely, I’ll 100 percent sign that. But when it comes down to what that actually means, there’s some very good potential for conflict there.

Disclosure: The organizers of Devcom paid my way to Cologne. Our coverage remains objective.