Game developer advocate and Vlambeer co-founder Rami Ismail has run #1ReasonToBe, one of the consistently most inspiring panels at the Game Developers Conference, for years. This year’s global diversity panel was his last one, and it was an emotional session about how game developers struggle to make games around the world — and why they still do it in spite of hardships.

They told their stories at GDC 2019 because Ismail and fellow game developers have created a safe space, where they can talk honestly about how difficult it is to make games. They can feel free to express themselves and inspire others by naming their #1ReasonToBe a game developer. I’ve attended these sessions for many years, and they have always been the highlight of the show, which drew an estimated 20,000 developers to San Francisco this week. (Ismail will be a speaker at our GamesBeat Summit 2019 event on April 23-24 in Los Angeles).

Games, Ismail said, “are a global language that we can all listen to. And play and playfulness are some of the most globally understood means of communication.”

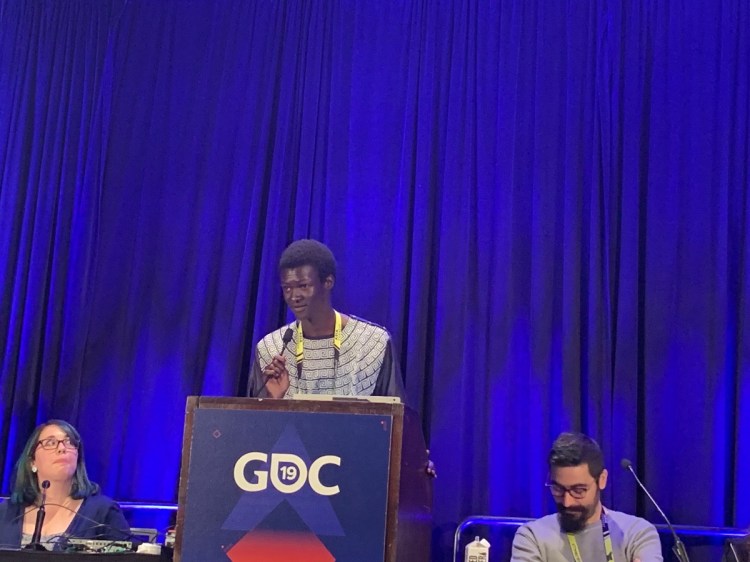

Lual Mayen

Above: Salaam is a mobile game about peace.

One of the talks featured Lual Mayen, who came to the GDC from South Sudan. He was born a refugee, during a time when his parents were fleeing a decades-long civil war, which displaced more than 2.5 million people. His refugee camp had no electricity, so he grew up without video games. South Sudan finally emerged as a separate country in 2011.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Mayen wanted a laptop. His mother saved for three years to get $300. When she gave it to him in 2013, he burst into tears. He took it to an internet cafe and used it. And he discovered Grand Theft Auto and the joy of playing. It was a three-hour walk to get here, but he made it regularly to charge it.

While many games were violent, Mayen thought about how to create a game that could inspire peace. He taught himself to make games and formed his own company, Junub Games.

“Living in a refugee camp is not easy,” Mayen said in his talk at the GDC 2019 panel. “I asked what is the best way to restore a sustainable peace in my country? My main focus was to contribute something to my country.”

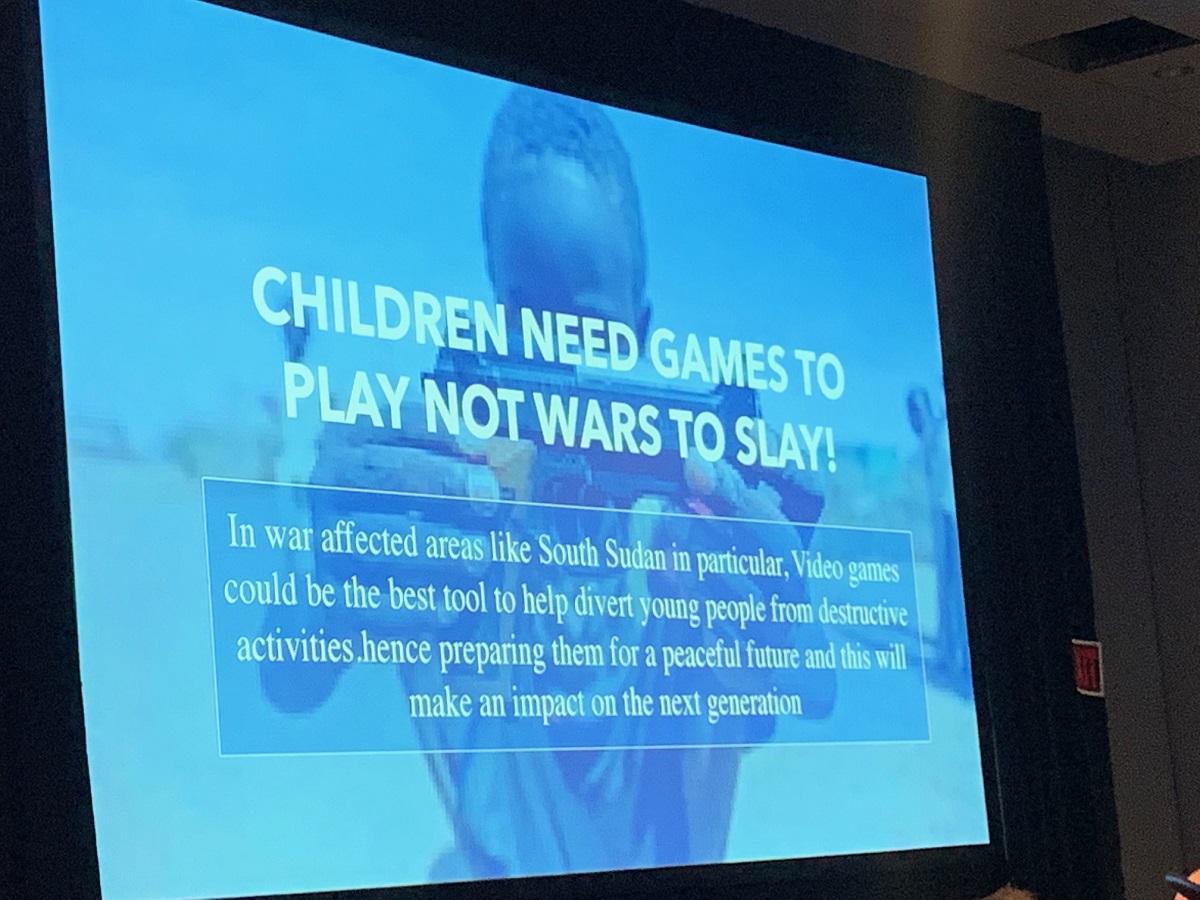

“I realized the power of gaming,” he said. “I realized games can be helpful for peace and conflict resolution. I started making a video game in my country so video games can divert their minds from destructive activities.”

Above: South Sudan needs games about peace.

He created a game called Salaam, about protecting communities from being destroyed. It was a 10-megabit mobile game, but he could only distribute it via Bluetooth networking.

Mayen met Ismail, cofounder of Vlambeer and a successful game developer, and Ismail encouraged Mayen to pursue his passion of making games. Now Mayen is making a board game, Wahda, that encourages peaceful conflict resolution, and he hopes this might be a better way to reach refugees.

Ismail pays for the panelists to come to GDC in San Francisco, but despite an invitation, Mayen wasn’t able to come in 2017 because of President Donald Trump’s immigration restrictions. His visa wasn’t approved in time. But Mayen made it this year, and he gave a hell of an inspiring talk. The talk brought tears to Ismail’s eyes and to mine as well.

Khaya Ahmed

Above: Khaya Ahmed

Khaya Ahmed wants to make games for change. She believes there are a lot of misconceptions about gaming and the career path to making games, particularly in her home country of Pakistan.

She was able to enjoy games at a young age with a Sega Mega Drive. She got hooked on Sonic the Hedgehog, and she started thinking about making games at age 15.

She taught herself storytelling and worked for years in TV and movies. She won awards, and only a few years ago she managed to break into gaming. She found a support network that allowed her to make mistakes without feeling bad.

“I want to change perceptions and I want to make content that connects with the audience,” she said. “We use games to change perceptions.”

Ehsan Ebrahimzadeh

Above: Ehsan Ebrahimzadeh of Arkane Studios.

He lives in Austin, Texas, but Ehsan Ebrahimzadeh grew up in Iran. He was obsessed with video games, playing titles like Doom, Age of Empires, and Prince of Persia. He dreamed about making games and thought about how to do it while in college. He teamed up with two friends and they started making their own studio. They created a World War I game set in the south of Iran.

Ebrahimzadeh worked multiple roles, focusing on the story, level design, sound, and art. They created a game called Shadow Blade: Reload. But they struggled, as they could not find any funding for game companies in Iran. Ebrahimzadeh decided he had to take drastic action.

“I needed to leave my country to pursue my dream. Leave family and friends. And compete on the level of a world-class stage. I had visa complications and a huge risk,” he said.

He compared his own art with the best in the industry and figured out where he had to improve. Eventually, he got a call from Arkane Studios, which opened a studio in Texas. Arkane made games such as Prey. He got a job and made it to the U.S.

“I was not alone,” he said. “My wife, a [doctoral] student, was beside me. My mom and dad were beside me. I had all of you who inspired me and motivated me to push forward, believe in myself, to be resilient, and be resourceful.”

Nourhan ElSherif

Above: Nourhan ElSherif

This woman lived in Egypt and had her visa rejected, but she asked the panel to read her story, and they complied.

Early on, she fell in love with video games and decided she wanted to make video games. But she was told there wasn’t much future in it, because no one in Egypt made games.

Still, she said, “Something inexplicable drew me to it like a magnet.”

Then she said that a “miracle” happened. The Global Game Jam was held for the first time in Cairo in 2013, and she attended it and learned about a nine-month game development training program. She attended that and learned some things about making games. She found a group of other would-be game developers and banded together with them.

She and her friends worked regular jobs to earn money and then worked on a game in their spare time. Their goal was to become full-time indies. They made a game called Keys to Success. But she still had a hard time finding a full-time job. Egypt fell into economic troubles.

One studio rejected her because she had a “high chance of getting married.” But she persevered and found work.

She said, “I will keep allowing games to inspire me until one day I can inspire people through games too.”

Juan de Urraza

Above: Juan de Urraza

Juan de Urraza always felt video games would become the most artistic creative media in the history of humankind. He felt they were more influential than movies, books, and music. But he lived in Paraguay, and making games for a living was not an option.

When he was eight, he played games on a Commodore 64. He was shy and lone and fell in love with role-playing games and strategy games and graphical adventures. But he started writing science fiction and fantasy books. He stayed in that work for 20 years, staying away from the idea of working on games.

Then, when he turned 40, he decided to go back to games. Digital distribution had come to his country, and so he quit his job. He started a company and raised a small amount of money. They worked on a location-based title dubbed Fhacktions and built it over four years. It won an indie prize, and it won an award at a Google Play Festival for indie games. It got more than 300,000 downloads, and it did well in Asia. But was not a financial success.

He helped create a game conference and fund the Latin American Game Development Federation. They raised funds for 100 Latin American developers to attend the GDC for the first time this year.

The team is looking for investment for a new location-based game. Urraza wants to continue to making games.

“I’m excited to go on this journey, learn, and share it,” he said.

Camila Gormaz

Above: Camila Gormaz is founder of Bura.

Camila Gormaz is a developer in Santiago, Chile. She wanted to be an indie game developer since she was 10. She grew up watching arts and craft shows and wanted to make things on her own.

She could not afford a game console. But she played with friends and tried to make her own game levels with pen and paper. She asked her friends to look at them, and she said, “They gave me very harsh feedback.”

Later on, she got hooked on role-playing games. She taught herself HTML and started making simple web games and Flash games. She learned about storytelling, game design, and digital art. But she could not find any jobs in gaming, and she lost hope. She could not afford to leave Chile. She worked on web marketing.

Eventually, her art got noticed and a European developer hired her to make some art. That led to more games. She regained her confidence.

She started an Indiegogo campaign, and it was successful. She used the money to start her own studio, Bura. She launched her first game, Long Gone Days, on early access on Steam last year, and now the team is working on the full release.

“I want to keep making games forever,” she said.

GameDev.World

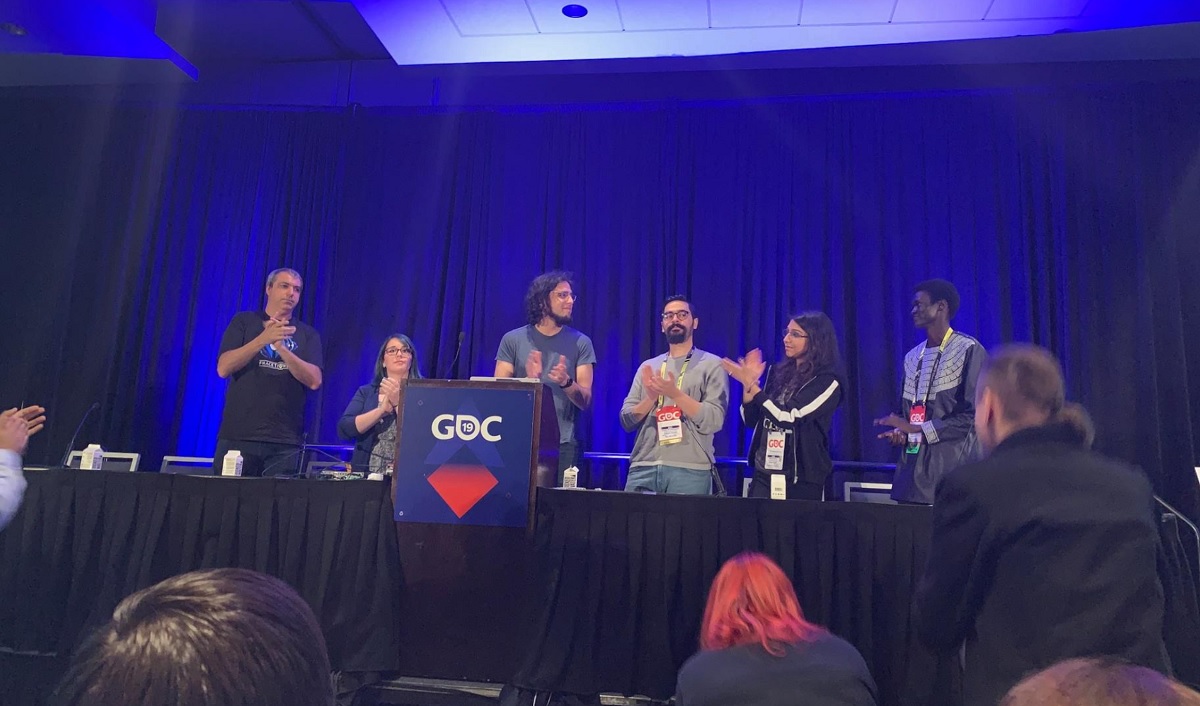

Above: Rami Ismail is at the podium.

Ismail said, “This is the final time I am hosting the panel.” He noted that it was started by Brenda Romero and Leigh Alexander to tell inspiring stories about why women made games. They asked Ismail to take it over to address geographic diversity issues. Ismail did so, but now he believes it should be returned to its original purpose, as a panel for women. He hopes someone else will pick it up.

In the meantime, he is starting GameDev.World, an online-only conference that will debut for the first time in June as a global game development conference. It will be translated live into eight languages and will feature talks from game developers from around the world.

After the panel was over, Ismail got a standing ovation.