Sam Barlow’s interactive movie game Her Story won numerous awards in 2015 because it was a novel way to tell a story about a police interrogation of a woman suspected of murder.

Now Barlow is taking that a step further with Telling Lies, a new game from Annapurna Interactive that features a bigger cast. This game’s video scenes include actors Logan Marshall-Green (Prometheus), Alexandra Shipp (X-Men: Apocalypse), Kerry Bishé (The Romanoffs), and Angela Sarafyan (Westworld).

Annapurna released a teaser trailer today for Telling Lies, and I interviewed Barlow last week at the Game Developers Conference. We talked about how he wanted to avoid a sequel but stay with the game mechanic of searching through a trove of video to find clues about an intricate story.

In this case, a woman gains access to a trove of data collected by the National Security Agency through surveillance. As a player, you have to search through the data to piece together a story of what happened, including why the people were under surveillance. The trailer says players have 96 lies to decipher and one big truth to uncover.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Barlow is dropping a few hints of what it’s about and how the gameplay works. But he wants to preserve some of the mystery for the game, which comes out later this year. Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

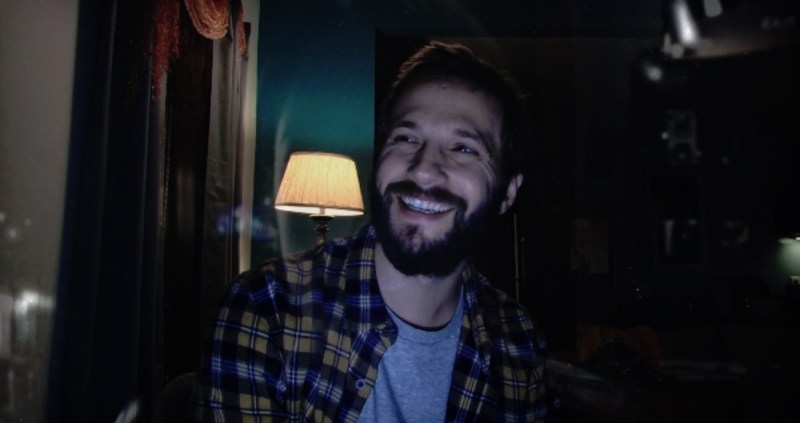

Above: Sam Barlow is the creator of Her Story as well as Silent Hill: Origins and Silent Hill: Shattered Memories.

GamesBeat: Tell us what this is about.

Sam Barlow: This was our attempt to show some of the texture and color of it, and our cast, without actually revealing anything. That was the goal. The whole project is — I made Her Story somewhat — that was a process that was somewhat naive, or at least intuitive. At no point did I stop and interrogate some of what made that game interesting. It always made sense. Even the fact that I was using live-action video in a game, and using it in a way that was different to how most people have used live action. It just emerged out of the process and make sense and felt cool to me.

Then I released that game, and people said, “Wow, why did you make an [full-motion video] FMV game?” I didn’t actually realize that was what I was doing. It was just a series of decisions I made. I didn’t immediately want to do a direct sequel to that game. It’s one of those things where, if you make something particularly different, you have that question of, is this a one-off? Is it a genre? Is it something we can dig further into and play with these mechanics?

I allowed myself to have some space. With perspective and distance, looking back at Her Story and figuring out what was interesting to me about what I did there — what are things that, now, having done that one — I think there are interesting things I can do. For me, a lot of those questions were — people would call that game an interactive movie and compare it to that whole tradition. I would struggle with that, because it’s not actually very movie-like. It has filmed performance and uses video, but it’s very much a different take on it.

This game was me really interrogating that and saying, “What is interesting about serving the story up through these bits of video?” Giving people that non-linear way of searching through it, having them pay attention to what’s being said in the clips and using this kind of leap pad that allows them to teleport around the narrative. Really doubling down on that.

Above: Telling Lies actress Alexandra Shipp

This game is about the four characters we just saw there (in the trailer), four main characters. A series of relationships that connect them. We have these discrete stories that bounce off each other and intersect. The whole format here is, you’re watching conversations that occur over the internet. You’re seeing people Skype each other. You’re seeing cell phone footage. You’re seeing a few other bits and pieces of camera stuff. But it’s all these intimate conversations between people in these domestic spaces. It’s the equivalent of pillow talk. It’s people in relationships, husbands and wives, fathers talking to their daughters.

It’s a texture that’s very non-video game. Most video game stories are about the big action beats. They’re about people going off to war, post-apocalyptic things, big dramatic scenarios. This is going in the opposite direction, digging into the minutiae of their lives, seeing them in private contexts talking to each other.

GamesBeat: It’s a small cast, too? Not a large movie cast.

Barlow: There are slightly over 30 speaking roles. The interesting is that we have a story where there isn’t necessarily a single lead character. It’s a bit of an ensemble piece. But because of the way you access it, you find that you kind of anchor yourself around one of these characters, or are drawn to one of these characters. We had a series of playtests where people would play the game for three or four hours, and then afterward we would ask them to narrate to us, what is the story of this thing? Summarize the story in a few lines.

Different people would say, “Well, it’s the story of this character. This is what happens.” Someone else would anchor around a different character. You get these very nice subjective slices through the story, which I think is — I said earlier that I only realized when we were shooting this that to some extent, I’d been thinking a lot about shows like Breaking Bad, where there’s always that tension of the anti-hero protagonist. You had that weird thing where sometimes the audience loved him and thought he was a superhero and really cool. Their attempt to balance the anti-hero-ness and question his actions, question whether he was redeemable, sort of fell on deaf ears.

To some extent that felt to me like a constraint of telling a linear story on television where you have to have a main character, and you have a certain act structure. By the end of that series, they needed him, to some extent, to go out and tie up loose ends and finish cleanly and redeem that character. Here we’re telling the story with all these layers and all sorts of questions about characters’ motivations, whether they’re truthful or not, whether their actions are good or bad. We don’t lay out this linear sequence of events. We don’t identify somebody as the main character, and therefore you’re naturally drawn to empathize with them, because that’s how stories work. It creates a very interesting way of dealing with questions about character motivations.

Above: There are more than 30 onscreen characters in Telling Lies.

GamesBeat: Are you using the same mechanic, reassembling clues that are in fragments?

Barlow: The premise here is, when it opens, we establish the frame narrative, where you see — it’s night and this woman jumps out of a car and runs into this dark Brooklyn apartment. She opens up her laptop and she has an external hard drive with her. She plugs it in and boots up, and she has a stolen NSA database. This database is full of all this surveilled footage, captured footage of these people having conversations. It spans about two years in time.

You instantly understand that something bad has happened. Something on the level of government and law enforcement has occurred. There’s a reason that all these clips have been gathered together. There’s a reason why these people are interesting, and why this woman is digging into this footage. In a similar way as with Her Story, you come in and the hook is you have to solve a murder, but you can do that reasonably quickly. It then becomes more about the whys, digging into this character’s weird Gothic backstory.

That was the portion of Her Story that I found most interesting, this deep character study. People feeling like spending all that time with this footage of Viva talking to them and listening to her words and jumping around. They felt like they’d had something closer to a real conversation, that they knew her in a way that you wouldn’t always with a more traditional video game character.

So yes, it’s similar premise in that you have this database of footage you’re searching through. A few tweaks have significant ramifications for how it actually feels. Whereas in Her Story you were seeing little snippets — every little answer Viva gave was its own little clip — what you find here is whole conversations. The longest thing we have is about 15 minutes. Generally they’re a few minutes long.

When you search for a word, you’re dropped in at the point where that word is spoken. You might have this whole conversation here, and you might have a scene that starts here, goes here, and then ends at a dramatic moment. You’ll get dropped in at the middle of the drama, and instantly you wonder what the hell’s happening. You have that inferring of what’s going on.

Above: Logan Marshall-Green is one of the stars of Telling Lies.

There’s a big emphasis here on scrubbing through the video, which is its own mechanic. This is a beta version with lots of unfinished, uncolored footage. You search for the word “love” and you get dropped in here, where a character says, “Love you,” and then hangs up. End of conversation. Now you take your finger and you have this analog ability to scrub through it, like an old editing machine.

You find yourself watching scenes backward, because you have the subtitles and you have control of the speed. It’s about the journey rather than the destination. The point of scrubbing is not jumping to the start of the clip. It actually allows you to watch it in a different way. It further adds to this non-linear jumble. Not only are you jumping around time and space, but within scenes themselves, you have this freer attitude to the direction of time. It creates an interesting texture where you’re exploring — if Her Story kind of touched on this, this is very much saying, “The level design is the video.” This is a game where you explore video in the way you would explore 3D space in a normal game.

The game that I keep comparing myself to — the one game that, when I played it, felt like what we’re trying to do here, in a very analogous way — was Breath of the Wild. There’s something about the way, in that game, Nintendo just dropped you in the world, stepped back, and let your curiosity lead you around this world. You could go anywhere you wanted, genuinely, and it would always be interesting and rewarding.

It was such a stripped-back open world that when I play most open world games, if I’m here and I have to go from A to B because I need to go get five pieces of coal to complete a quest, it’s a bit of a chore. As I’m going from A to B, I’m noticing other objectives appearing on my map and building up more chores to do. Whereas with Zelda, it was like — there’s a joy in just walking through the world, walking through a field or a copse of trees, cresting a hill and finding a little pool.

There’s something about how safe you feel in a Nintendo game. If I was walking in that world and I saw something over here that drew my eye or made me curious, you felt comfortable just going off and exploring, letting yourself loose in that world, letting curiosity drive you. Some of that is — there’s a generosity of spirit in that game. They understand that the core fun of that thing is existing in this landscape. The landscape itself is handcrafted and beautiful. It’s not something they got the junior designer to cut and paste and fill out the space.

Similarly, here, we have hours of this footage that takes in all sorts of locations and characters and colors and textures and interesting scenes and little bits and pieces. We drop you in and let you scrub around and explore it. Then you see a word or phrase or something mentioned that you can then quite happily follow. You pick out that thread and jump around the story. It’s trying to give you that similar feeling of there being an abundance of interesting content, and you’re completely free to explore it at your leisure, defining what’s interesting to you, with the reassurance that if you follow a thread, it’s going to be worthwhile.

GamesBeat: When you’re building this, do you just write a story from beginning to end, and then break it up into a million pieces? Is it the player’s job to reassemble that?

Barlow: On a certain level — the thing I realized in doing Her Story — when I had the rough idea of Her Story, my initial instinct as a traditional game designer was to create a flowchart. It’s a puzzle, so if you find this keyword, that leads to this word and then that word. I started trying to think about that and realized that it felt really complicated and horrible.

I did a test where I found a series of transcripts online from a real homicide investigation. I grabbed all the text out of them and stuck it in a rough prototype of the game. I was playing it, and because I didn’t know anything about this case, I had the ability to play it as a player, rather than knowing what was going on. Very rapidly, I realized that naturally, the way language works, the way people try to hide things but reveal themselves through how they talk, the fact that there was this group of detectives trying to lead this guy to — they were asking him open questions so that he would talk to the extent that he’d incriminate himself. I found that I was uncovering threads through this story because of how language works. I was uncovering nice thematic links between disparate anecdotes. It felt like a magical thing.

Even though there wasn’t a game designer orchestrating that conversation — it was a real conversation people had — this idea of navigating things through language worked. Because there were enough layers, because this guy was trying to lie, because there was a reason for him to lie, it all worked. Then, when I did Her Story, I realized that all I needed to do is make sure I had a story with enough layers to it that it’s worth peeling them back. When I write this, I need to write it in such a way that people are speaking with subtext. They’re holding things back. The way they phrase things is revealing of this subtext.

There was a process of breaking the story down, and then going off and writing an essentially linear script. It’s very much from the character’s perspective. This is what happens in each scene. Then the bit that was the special sauce — and I refined the process on this project — was to take the finished script and run it through the computer and have the computer look at all the different words and linkages and how interconnected everything was. Then the computer would say, “This scene here is going to be hard to find, because the language used is not unique enough. Or this particular thread is too prevalent.” Then I would go in and tweak the words we used, and some of the structure, to balance out the interconnectedness of those things.

It all came from a very real place. It was written from the characters on out. Then there was a bit of calibration to make sure that this was pleasant to explore.

Above: The user interface for Telling Lies. Can you dig out the truth?

GamesBeat: But you didn’t have to have the actors reshoot things, did you?

Barlow: No. That process resulted in a script which was well-balanced, and then the challenge is that they had to go perform that script. They can’t rephrase things. As we found, the hardest thing was adding words in. If it’s a very dramatic scene, it’s easy for an actor to start ad-libbing swear words or throwing in things in the moment, because it’s so tense. Then we’d say, “You can’t do that. If you say ‘fuck’ here, you’re stealing it from somewhere else.” That was an interesting process for them.

GamesBeat: They had to understand that their words had some impact.

Barlow: Right. The process of breaking the story on this one was super interesting, because of this premise that we’re only seeing the moments in these characters’ lives where they’re talking online, or using their phones, that kind of context. What that means is, if you have the spine of the main story, a lot of the big actions, a lot of the big plot points, are happening off-screen.

You have that weird thing like in a found footage movie. Often your suspension of disbelief is tested when, by the end of the movie, they’re being chased by monsters, and they still remember to film themselves. Here we use that to our advantage. We’ll only see the story when it makes sense that these cameras are running and they’re talking online, which means that a lot of the big events that are happening are off-screen. You imagine them and infer them, which becomes very interesting. It’s like in a Shakespearean war play where someone runs in from off stage — “Oh my God, the battle! I saw my friends slaughtered and only I made it out alive!” And you’re imagining this incredible battle. There’s something interesting in this jigsaw piece of a story, figuring out what’s happening through the negative space, through these more chilled-out character moments, through these pieces of dialogue and intimate moments between characters.

In some ways, that solidified this idea for me that this is almost like an anti-movie. If you were to tell this story as a movie, you’d probably shoot all the action. You’d shoot the specific plot points. You wouldn’t necessarily see these scenes. But it takes on a life of its own. There’s one scene where there’s around seven minutes of Logan’s character washing dishes. In the recent Twin Peaks there was a famous scene of four minutes of someone sweeping a floor. Some people loved it and some people hated. In the context of that — I’m going to watch a 50-minute TV show and sit through four minutes of nothing — it was excruciating.

But here, because you’re choosing to watch it and discovering it, it has the texture of something you’re chancing across, something you’re spying on when you shouldn’t be. In the context of the story it suddenly becomes super interesting. If you know what has just happened previously in the story, if you know what’s going on with Logan’s computer screen while he’s doing this, suddenly there’s a reason to lean in and scrutinize what’s going on with his face. It’s an interesting texture.

If Her Story was an attempt to give people some of the sensation of what it’s like to actually write a story, where you have this big picture view of the whole story and you’re jumping around — I might write a scene here, and then jump back here to set up that scene. I’m seeing a particular character’s thread run through a story and making sure that makes sense. I think that’s an interesting place to be inside a story. I can make players feel like that. Here, doubling down on this idea of what it means to use video in this way, I wanted to give people some of what it’s like to be in the edit room. You have all this footage of the performance and you’re deeply immersed in it.

But then you’re looking down to the level of choosing which frame to cut on. Do I cut to this reaction? Do I stay on this person’s face? There’s a level in that scenario where you really appreciate and enjoy the subtleties of film performance that I thought was really interesting. Giving you this sheer amount of footage here, giving you the ability to stop and move through it and scrutinize it, is a super interesting texture.

Above: Kerry Bishé starred in shows like Scrubs and Argo.

GamesBeat: This reminds me somewhat of Detroit, where they had three different threads of stories going. But there they showed you the flowchart. Here’s what happened if your decision went that way, and all the other consequences. Eventually, it all comes together. Or something like Quantum Break, where you go back and forth in time and start erasing some of the threads.

Barlow: It’s interesting to deal with that problem of how you manage complexity for your audience. I always struggle — I remember having conversations with Sony a long time ago about making a different game. It was around the time they were doing Heavy Rain. For the execs at Sony, the thing they couldn’t get past was, if we’re going to shoot all these alternate branches, if we’re going to have all this content, we want players to know we’ve done that, that we’ve gone to that effort. They wanted, when a particular scene was happening, to do picture-in-picture with the other version of the scene that you could have gotten, so you appreciated how much effort went it.

I thought that was kind of shitting on the player’s choice. Also, it exposes the mechanics underneath. It makes it all less like a thing that you own and have earned and have your own perspective on. I think there’s something about — it was a small indie game, and I wasn’t answerable to anyone, so I was able to respect the player’s intelligence and trust them that I wasn’t going to overexplain this thing.

It was going to be reasonably opaque up front. I was going to let them look at this stuff in any order, put it together, and trust that the challenge of the curiosity that is piqued by having to work a little bit would actually be enjoyable. Particularly in an interactive sense, if you’re being dropped into a story and you have to infer the context and figure out the relationship between these characters. When you’re seeing someone speaking, you’re figuring out what they’re really saying, what they really think. You’re putting together this larger plot. Having seen this scene, now you realize what was happening in this other scene.

There’s a lot that you’re juggling. But it’s pure brain food. Our brains love to look at other human beings and infer what’s going on in their heads. We love to dig into people’s stories. There’s a texture you have in a novel, spending all that time in a character’s thought process and seeing their life from the inside out. It’s very unique to that form, but we get to touch on a little bit of that just because we’re not curating the story in quite the same way we normally would. We can let scenes unfold at a certain pace.

Someone asked me yesterday if I was interested in voyeurism if that was a thread through this thing. I was saying that for me it wasn’t really voyeurism. The thrill of voyeurism is watching something you shouldn’t. It’s the illicit feeling of watching something and being surreptitious. What interested me here, especially with sticking you in all these camera conversations, was getting some of that proximity you have to a character in a novel. When you read a novel and you’re in the character’s thought process, in the minutiae of their lives, it doesn’t have the naughtiness of voyeurism. It doesn’t have that queasy, sleazy feel to it. I wanted, with this, to take you into these characters’ lives, into their intimate conversations, but in a way that promoted empathy, made you feel closer to them.

That was one of the things I picked up in Her Story. Early on in that, when we first did a read-through, I had the camera up here, as it would be in a normal police interrogation room. You have this more voyeuristic feel when you’re watching it. As we did the read-through I tried putting the camera down here, so it was opposite Viva. We were putting you across the table from her. It completely changed the feel of the whole thing. Suddenly it went from being less about the detective interrogating her and her as the suspect, and it became much more about listening to her story, empathizing with her. The act of playing that game for a few hours and immersing yourself in hours of footage, being sat across from Viva, it created this sense of connection that I thought was super interesting, a texture I loved.

The process of playing this game, where you have these people having conversations — you’re always seeing one side of the conversation. You’re always put in the position of being in the conversation. You don’t have that distance that you would if this was a David Lynch movie, where you’re filming through the closet spying on what people are saying. That, for me, was very important.

Above: Angela Sarafyan was part of the Westworld cast.

GamesBeat: It sounded like this would be more ambitious. Has it taken a longer time to do this than Her Story?

Barlow: Yes, we took longer to write the thing. It’s an order of magnitude bigger, and not necessarily deliberately. It wasn’t a case of feeling like, well, this is a sequel so everything needs to be double. It was more a case of, this is the story I want to tell. To tell that story we’ll have to pull in these characters. We have to go to these places and see these things. When we finished the first pass of the script, we looked at it and it was very big. We asked ourselves if we needed to edit it down, if we were being too ambitious. The feeling was, this is what it has to be. To tell this story, this is how it pans out.

And then it took longer on the back end, because of the process of casting something like this. Having essentially four lead characters in it, you’re trying to balance the schedules of different actors. That was a huge, complex piece of planning.

GamesBeat: You couldn’t shoot it in one whole piece with one person, and then go to the next?

Barlow: No. A big thing that was fundamental to it to me, if you’re in this world where two people are talking to each other through cameras and there is an intimacy — there was a naturalism we wanted to get. There are pauses in conversations. The pacing of these conversations is different. The way they speak is more — we want the sense that you’re wandering and being dropped into the middle of something real that’s happening. It was important that there was a genuine chemistry between the people on either side of the conversation.

The way we set out to film it was, everything was shot on location, but we took over this compound where we had multiple houses, apartments, a couple of other buildings, miscellaneous bits and pieces, and we had two separate teams running simultaneously. We would have Logan in an apartment over here. We’d have Carrie in this home over here. They’d be operating this rig that was playing the role of a cell phone or a laptop or something. They would be acting against each other in real time in these two completely separate locations, so that — if a fun thing you’re doing in this is watching someone’s face while the other person is talking to them and these scenes are unfolding and more dramatic things are happening, it was important that that be genuinely interesting and real. Having the actors bounce off each other created that.

There’s a whole thing where you can kind of infer who’s on the other side of a call just from the body language and the chemistry. Everyone has different bits of chemistry with each other. That was, just from a logistical point of view — everyone that worked on this was being stretched and having to figure out how these things worked. We’re filming this huge script and we’re shooting two scenes simultaneously. The job of just booking the actors to be in the right places at the right times was a huge deal. We shot for three months with a little break in the middle.

GamesBeat: It seems like you’re operating in this border between games and movies. When it comes to accessibility, what’s accessible here — I think about things like the Angry Birds people talking about how they reach 4 billion people. There might be some limit on the number of gamers out there, so they do the Angry Birds movie for everyone else. If you had a story like, say, The Last of Us, you could reach a certain number of people, but once you take the zombie game out, maybe you could reach even more. The story goes even broader.

Yours is interesting in a different way, though. You’re making people do a lot of work, a lot of thinking, a lot of replaying. It’s not an easy experience. It’s not a passive experience. It’s movie-like, but it’s not a passive experience.

Barlow: What surprised me with Her Story, the most exciting thing about Her Story, was I didn’t set out to make — I set out to make something that was different from other video games. I set out to throw out some of the things that I’ve had to do if I was making an action-adventure for a publisher. There would be certain things that would be givens. I was definitely conscious of wanting to step outside of that. But I wasn’t making a big play for mega-accessibility.

Above: Her Story goes as far as to emulate screen flare in its old-school look.

By accident, having something that is a character-based story with strong stakes and lots of emotion and interesting story there, that was naturally something that appealed to people. The genre trappings appealed to people.

GamesBeat: And they’d never seen something like this before. It was different, and that made it more widely appealing.

Barlow: The interesting thing is, as you say, it asks a lot of you, but it’s using muscle memory from how we use the internet. It’s using muscle memory from how we do stuff now. You’ll go down a rabbit hole of googling something and following a bunch of links. Before you know it you’re reading some obscure Wikipedia article about such-and-such. How did I get here? You’ve followed this chain of things. We juggle so much information.

I remember reading an article that was in defense of reality TV. They were taking on the criticism of, “Oh, TV today is crap, we have all this reality TV, it’s trashy nonsense.” Their point was, back in the day — you shouldn’t be comparing with trash reality TV with whatever premium play of the day show you remember from the ‘60s. You should be comparing it with the trash from the ‘60s. The trash from the ‘60s was game shows. This was your vicarious entertainment where you get to see a real person go through a gamut of emotions. That was frivolous nonsense. If you’re watching the Kardashians, compared to that trash, this is trash that requires emotional intelligence. It’s about people and relationships. It’s actually a much more complicated and interesting version of trash entertainment.

I think a lot of what Her Story was doing — it was asking a lot of you, but it knew that we are all very literate in crime stories now. We’ve seen 101 murder mysteries in different forms. We navigate the internet and social media. We use these complicated devices in our hands now to do all sorts of things. It was leveraging all of that, which accidentally made it super accessible.

I find that, particularly for non-gamers, you had them a controller and try to teach them an FPS camera scheme, or you give them an Assassin’s Creed game and try to explain what all the buttons do — those games have something like four hours of tutorial in them to explain all the different mechanics. That’s a huge barrier, because you’re asking people to learn something brand new. There’s a level of abstraction to some of those game mechanics that they have to be introduced to.

Whereas, accidentally, Her Story was not asking you to understand any new abstractions. It said, “You know how to search things. You know how to watch things. You’re interested in looking at people and inferring context. You know how twists and reveals work in crime shows. We’re asking you to go a little bit further and anticipate some of those yourself.” That was one of the beautiful things. I accidentally found an audience that was much broader and more diverse and more interesting than the traditional video gaming one.

Above: Sam Barlow believes imagination is the best game engine. He spoke at our GamesBeat Summit in 2016.

GamesBeat: There might be this big genre in between movies and games. It’s not just a thin line.

Barlow: The awkward conversation I’d have was with people saying, “Oh, my partner introduced me to this thing. I never played video games before. I love it, and I realize now that I’m a huge video game fan. What should I play next?” Well, most games aren’t like this. This is a very unique thing.

GamesBeat: Things like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch may be in the same place.

Barlow: It’s becoming more interesting because all of the players in traditional visual storytelling are seeing the world change at this ridiculous pace. Network television, which was the bedrock of advertising, of mainstream storytelling, is slowly dwindling. We now have streaming and the ways it has changed our viewing habits. They’re terrified because they look at kids and see them spending more and more time gaming or on social media. Yes, they’re binging Netflix shows, but the proportions are shifting. The way they navigate media is a world apart.

Every one of those players is trying to figure out how to add interactivity. How do we take the feedback loops that keep people in social media, that keep people playing their favorite video games, that make them rewarding and make them feel personal and more immersive, that that boost the social value of those things — how do you inject those into what we understand, which is a five-act TV show? Or a 30-minute sitcom. There’s a whole wide range.

GamesBeat: Do you think you’d like to watch somebody stream this with an audience and try to figure it out?

Barlow: There were some great examples of people doing that on Her Story. Financially, they weren’t satisfying, because two million people are watching a stream and one person has bought their five-dollar copy of Her Story. [laughs] But that’s the nature of the beast now.

There was one — I can’t remember the name of the streamer — that had this huge audience, and they had a public Google doc open. Everyone had been assigned a different role. Someone was transcribing what was being said. Someone was noting what clothing was being worn. Other people were adding suggested keywords to search for. Other people were keeping track of time and date for all the events. It was so cool. I can’t remember how many people were watching concurrently, but say it was about a million people watching. It was one of the biggest streamers. That’s a stadium of people collaboratively playing my game. That’s so cool and interesting.

That was some of the special sauce of Her Story. Multiplayer gaming is, I’ve found, with a more general audience — it can be super excluding. There are a few examples like Mario Kart and stuff where Nintendo knows how to make that work, but I find that if I want my wife to sit and play something with me, there’s that awareness of skill being an issue. “I’m not going to be good enough, fast enough. I’m not going to understand the mechanics enough to play well.” Often one player or another will have a more interesting task to do. It’s hard to negotiate that. If you’re watching someone else play a video game, that can be very excluding as well, because the person with the controller is having all the fun. They’re expressing themselves.

The beautiful thing with Her Story was because the gameplay was watching, observing, calling stuff out, interrogating the story, and making connections, the person who was sitting on the couch without the controls in their hands was just as involved and had just as much agency in the experience. Then it became interesting. “Oh, this is what’s happening!” “No, I don’t think so.” “Search for this and we’ll see!” I created a super interesting co-op experience that didn’t have all the barriers you might otherwise see.

Even if you look at a conventional TV show now, coming out once a week, it comes out, and as everyone’s watching it we’re all live-tweeting and discussing it. We’re cleverer as a collective than we are as individuals, so people are calling out the plot twists two episodes ahead, screen-capping, notching little Easter eggs. Then, the next day, you sit and read two or three recaps of the thing, which is an interesting critical dialogue alongside that. You’re digging into the thing and there’s this shared discussion. Then you go on Reddit and people dig into it even more. Even that very classic form of television is now massively cracked open and becoming something that’s more collaborative. It has a life of its own.

GamesBeat: Do you worry in this case that people might spoil your big plot points? Or is it in some way resistant to that?

Barlow: There’s obviously a joy in a big plot twist or a big reveal that is super cool in the moment. You know examples from games and TV where you’ve sat there and suddenly, “Oh, shit!” Bruce Willis is a ghost, whoa! But the good twists, I think, are the ones where you then go back — the good movies are ones you can watch two, three, four, five, six times and they get better every time. Often that is because you now have the dramatic irony.

To use the Bruce Willis example, is it interesting to go back and watch that, now knowing the nature of his character? Possibly that’s a richer, more interesting experience. What’s interesting about this is, every twist or reveal is just layering on more and more information and more and more context. There are going to be fundamental questions in this story around things like, why did someone do something? These are interesting questions. Were their intentions true? What was really going on in this character’s head? Is this character a good or a bad person? Did they truly love or not love this other character? These are the questions prompted by the story.

The more you watch, the more you rewatch, the more context you understand, the more nuanced an answer you have. But it’s fluid. These are interesting questions that I think people will enjoy. They’ll have different versions of the answers because they’ll approach the story from different angles or have different anchor points in the story. When we did the focus tests — when we sent them to lunch, actually, was even more organic. They played for two hours and went to lunch. Then they’re swapping notes and discussing things. You’d see little arguments about interpreting certain things, what certain things meant, and someone would say, “But did you see the bit where so-and-so did this?” “No! Now I need to go watch that and have my take on it.”

It’s hard. This week, I’ve been trying to negotiate not spoiling the thing. I’m speaking very vaguely about the storyline. We had this discussion around — for most people, if they play the game for five to 10 minutes, they’ll establish some of the core aspects of the story, what’s really going on. We’re discussing, well, is it okay to just have that be in the trailers, then? It’s quite standard to say, “Okay, we’ll show people the first hour of the game, but we’ll keep all the cool surprises after that secret.”

But I think in this case, that first five to 10 minutes feels slightly sacred because the thing is so wide-open. We don’t really lead you. Those first minutes of the game are where you really imprint on it with your own subjectivity. You’re attracted to certain threads or characters, and that pulls you off in a certain direction. We saw with people playing it that you have this wonderful spread of people going off and exploring in very unique, subjective ways. There’s definitely part of me that knows going in clean and experiencing everything fresh is great. But there’s enough going on, and enough bits and pieces to the story, that I think you can spoil it as easily.

It’s interesting. Her Story is two or three hours for the core experience. You can play it for a bit longer. Just from a commercial perspective, it sits in that uncomfortable zone on Steam, being a short narrative game. Which actually — we didn’t really have a problem on Her Story. Also, as a streamable thing, you have that weird challenge of — if you’re watching someone stream Minecraft, that doesn’t inhibit you from wanting to go buy Minecraft. You’re seeing the cool stuff they do and you want to go play in that toolkit. You want to go do your own fun thing. Whereas if I watch someone stream The Last of Us and I see the whole thing, I’ve kind of got the experience of The Last of Us at that point. I don’t feel incentivized to go play it myself.

Above: Sam Barlow wins the grand prize for Her Story at the Independent Games Festival.

GamesBeat: Do you think this is one of those things like God of War, where it could be 20 hours in a straight shot, or it could be 40 hours if you take your time? Do you have a wide range of how long this might take?

Barlow: We surprised ourselves with how big this one is. I like short games. I like games you begin and finish in a single sitting, that you can binge in effect. I loved it when people would tell me, “Oh, I opened up Her Story just to see what it was about, and next thing I knew it was 1 a.m. I was deeply immersed in the whole thing.”

When I set out to make this, in my head it was going to be roughly the same kind of thing. But we ended up making four or five times as much content in this, and the way in which you look at it and navigate it kind of makes things take longer. Not in a bad way. We accidentally made a game that’s reasonably big. Still, I think it sits at — in a handful of hours you can reach a point where you’ve had a satisfying full meal and you feel like you’ve had the experience. But then you can continue to dig away.

There’s something really nice as well about an experience where you can get deeply immersed in it, but walk away knowing there’s way more there if you want to go back. Again, to compare with Breath of the Wild again, there’s such a generosity of content in that, and it doesn’t necessarily feel stretched thin. You can put it down and then look forward to the idea of coming back at some future point and digging around and exploring and finding stuff.

I remember an anecdote of someone who had played Zelda for 60 hours, and then they picked it up and discovered the seaside village. They’d never seen it before. They thought, “Oh my God, this whole wonderful place full of interesting things was there all the time, and I never found it.” The idea that the game could contain interesting stuff like that and Nintendo was in no hurry to force you to find it, that you could just wander across it, was super exciting to people.

This will definitely live in that world where — the first time the footage we shot went into the game and was fully playable, I loaded it up, and even knowing everything intimately, I lost two or three hours just moving through it and enjoying finding my way around it. Amongst the small tweaks to the game now, one thing I wanted to do is to encourage people to lose themselves in this, and not feel the need to dryly kind of 100-percent everything. We wanted them to just get caught up in the moment.

One thing we do now if you see something that interests you, you just click the word, and it instantly drops you into a search. Then you’re in another scene. You jump around and see something else interesting and jump again. You can hypertext your way around this story, jumping back and forth through time and space, following threads at this pace that — the first time I put it in the game, I thought, “People are going to finish this in five minutes. I’m making it too easy to consume this.” But actually, the game is robust enough and there’s enough stuff there to support that. It’s such an intoxicating way, such an interesting way of consuming story. You’re very much driving it. Your foot is on the gas. You’re jumping around the story. It has a very unique feel to it.

Above: Wake up.

GamesBeat: Do you have a launch date yet?

Barlow: It’s coming soon. If all goes to plan, it’s pretty soon. A handful of months. The only thing that will stop us is we’re localizing it this time into a whole bunch of languages. They’re pretty bullish about doing that, but because of the role that language plays — we have this unique scenario where every different localized version has essentially different level design. Normally when you’re testing localization, you just make sure the German doesn’t run off the screen. Here, we need to make sure that in Italian, it still works. You can still navigate things and it still feels pleasantly connected.

That could slow us down, but everyone seems pretty confident that we can pull it off. It’ll be great because I definitely left eyeballs on the table with Her Story by not having it be localized. It’s always a hard thing. I was speaking to the guys at Inkle. They said, “There was no way we ever could have localized 80 Days.” It’s so complicated, with so much procedural text, that it would be impossible to localize it. When you look at the stats on the store page, though, and you see how much interest there is from certain territories, you realize the scale of things like the Chinese audience on Steam. It’s incredible.

Her Story was the first game I released myself, and it was also the first digital-only game, having made traditional games for publishers. I remember the first week of selling it, pulling up the world map and seeing where it was being sold. There was at least one copy sold in every country, pretty much, across the world, apart from Antarctica, because not many people there buy Steam games. But understanding the scale and the global reach when you release a game now, it’s fantastic.